Signalment:

Gross Description:

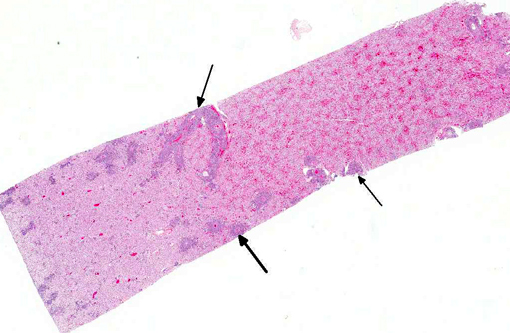

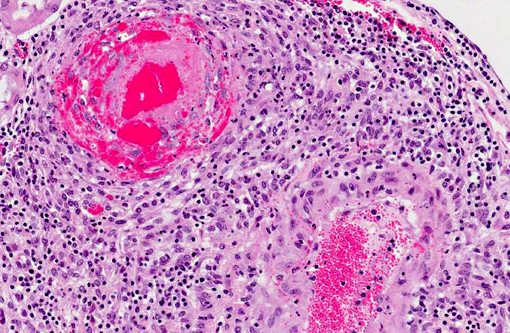

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Malignant catarrhal fever is a herpesviral disease with a worldwide distribution that affects certain wild and domestic species of the order Artiodactyla.(2) It is caused by closely related viruses in the genus Macavirus (sigla for malignant catarrhal fever virus) in the subfamily Gammaherpesvirinae.(4) The International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV) currently recognizes 9 species in the genus,(7) of which probably the best known are alcelaphine herpesvirus 1 and ovine herpesvirus.(2) Gammaherpesviruses have a propensity to become latent. As a result , the gammaherpesviruses have co-evolved with their natural hosts. Unless natural hosts are immunodeficient, gammaherpesviruses are normally carried asymptomatically. However, natural hosts act as reservoirs and are sources of infection to susceptible cloven-hoofed species that are not as highly adapted to the virus.(1)

Molecular phylogenetic analysis of a portion of the DNA polymerase gene that is relatively conserved among herpesviruses has revealed two major groups of MCF viruses. This is relevant not only because viruses within each group have similar biological properties, but also because it is suggestive of a shared epidemiology.(8) Most MCF viruses are named after their reservoir hosts, and the two aforementioned groups are the following (note: this analysis included viruses not yet classified by the ICTV):(7)

The alcelaphinae/hippotragine group, which includes AIHV-1, the virus responsible for wildebeest-associated MCF; alcelaphine herpesvirus 2 (AIHV-2), hippotragine herpesvirus 1 (HiHV-1) and MCF virus oryx (MCFV-oryx) which are carried asymptomatically by hartebeest, roan antelope and oryx, respectively, have not yet been associated with disease.(8)

The caprine group, which includes MCF viruswhite tailed deer (MCFV-WTD) of unknown origin that causes disease in white-tailed deer; MCF virus carried by ibex (MCFV-ibex), which is responsible for disease in bongo antelope and anoa; MCF virus in muskox (MCFV-muskox) and aoudad (MCF-aoudad), which are carried asymptomatically and have not yet been associated with disease; caprine herpesvirus 2 (CpHV-2) which is endemic in goats and has been associated with disease in sika deer, white-tailed deer and pronghorn antelopes; and OvHV-2.(8)

OvHV-2 is one of the most characterized causative agents of MCF. The virus is endemic in most domesticated sheep.(8,11) MCF-like disease has been experimentally induced in sheep by aerosol inoculation with high doses of OvHV-2; however, the disease is uncommon or non-existent under natural conditions.(10) The susceptibility of ruminant species to development of MCF varies significantly. P+�-�re David's deer, banteng (aka Bali cattle), and bison are most susceptible to disease, followed by water buffalo. Domestic cattle (Bos taurus and Bos indices) are comparatively resistant; for example, bison are 1000 times more susceptible to clinical MCF than cattle. The reason for this range in susceptibility is not known. Sheep-associated MCF has occasionally been reported in moose and pigs.(13)

There are few reports of sheep-associated MCF in domestic goats in Europe (Germany and United Kingdom). In two published cases, the most common clinical presentation included pyrexia and neurological signs, predominantly ataxia and tremors.(6,14) Necropsy examination of three goats in Germany revealed enlargement of lymph nodes and visceral organs with minute white-spots in the liver and kidney. One goat had erosions and ulcerations of the esophagus, and another had bilateral corneal opacity.6 Microscopically, goats in the published reports(6,14) had characteristic multisystemic lymphohistiocytic necrotizing vasculitis with fibrinoid necrosis, predominantly of medium-sized arteries. In the present case, neurologic signs were observed and included weakness of the hind end. Similarly, gross findings included bilateral corneal opacity, swollen lymph nodes and multiple, pinpoint, white foci in the liver, along with splenomegaly and prominent white pulp; erosions or ulcers in the alimentary tract were not observed in this goat. As in previous reports, the salient histopathologic finding was lymphohistiocytic necrotizing vasculitis, which was observed in the kidney, urinary bladder, spleen, lymph nodes, thymus, bone marrow, alimentary tract, liver and lung of this goat . Furthermore, meningoencephalitis as a result of vasculitis, marked hyperplasia of the splenic white pulp and of T-cell dependent areas of several lymph nodes were noted in this goat, which is also consistent with MCF. As with other cases, demonstration of OvHV-2 DNA by PCR in lesioned tissues, i.e. the kidney of this goat, supported the diagnosis of MCF.(6,14)

Vasculitis is rare in goats, and the lymphohistiocytic and necrotizing nature observed in MCF has been proposed to originate from a cell-mediated and cytotoxic process. MCF virus-infected CD8+ T lymphocytes have a tropism for blood vessels, where they infiltrate vascular walls and perivascular spaces. These lymphocytes express viral glycoproteins, which can in turn recruit lymphocytes and macrophages, and produce pro-inflammatory cytokines which are cytotoxic and cause injury to vascular cells.(15) This results in lymphoproliferative and necrotizing vasculitis.

The cutaneous form of MCF has been reported in one goat. That doe had multiple erythematous papules on the distal limbs that progressed to widespread erythema, localized scaling, and thinning of the hair coat, together with focal and moderate scaling and crusting of the peribuccal skin, nares and pinnae. Microscopically, granulomatous mural folliculitis was present, resembling that reported in two Sika-deer associated with a CpHV-2 infection. MCF-like cutaneous lesions, along with PCR analysis, were considered compelling evidence to associate it with an OvHV-2 infection. Sheep-associated MCF with generalized cutaneous disease, in the absence of other -�-�classical features, has been reported in cattle.(5)

In the published cases discussed above and in the present case, the affected goats were kept with sheep and other goats. Data on the OvHV-2 status of the sheep and unaffected goats in the herds was not available in any of the cases.(5,6,14) However, the source of infection was tentatively attributed to contact with sheep,(5,14) as they are the recognized reservoir host for OvHV-2.7 Although goats are the endemic carriers for CpHV-2, OvHV-2 DNA sequences have been detected in 9% of goats in North America, suggesting that goats can also be infected asymptomatically with OvHV-2.(11) The transmission from a herd of OvHV-2-positive sheep to na+�-�ve goats has been demonstrated in a study involving a low number of animals. On the contrary, transmission from a herd of OvHV-2 infected goats did not occur during close contact with other goats over a one year period.(9)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

There are five clinical patterns of MCF: per acute, head and eye, alimentary, neurological, and cutaneous. Most of the clinical patterns, with the exception of the cutaneous form, are associated with lymphoproliferation and/or vasculitis with subsequent necrosis in various tissues. The head and eye forms, characterized by ocular and nasal discharge, with lesions such as petechial hemorrhages and necrosis on the muzzle and in the mouth, are the most common forms in cattle. Diarrhea occurs in both the alimentary, and occasionally in the peracute form. The cutaneous form is distinguished grossly by alopecia with erythematous papules and crusts and microscopically by granulomatous mural folliculitis. It has been reported in cattle and one goat.(5,13) Rule outs for MCF include Jembrana disease, pestivirus, orbivirus, morbillivirus, or vesicular diseases.(2,13) Jembrana disease in Bali cattle (banteng) is caused by a lentivirus. Its principal lesion is a large number of intravascular macrophages filling and surrounding small to medium pulmonary arteries and veins.(3) Pestivirus (bovine viral diarrhea, border disease), morbillivirus (rinderpest, peste-des-petits), orbivirus (bluetongue, epizootic hemorrhagic disease, Ibaraki disease), herpesvirus (infectious bovine rhinotracheitis) and vesicular stomatitides such as rhabdovirus (vesicular stomatitis) and aphthovirus (foot and mouth disease) can all cause oral/enteric ulceration in ruminants; however, they are not generally associated with lymphoid proliferation and vasculitis.(2) Due to the variability in clinical presentation as well as its similarity to other enteric and vesicular diseases, laboratory confirmation of MCF, via PCR, ELISA or indirect immunofluorescence, is essential.(1)

References:

2. Brown CC, Baker DC, Barker IK. The alimentary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol 2. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2007:135-137, 140-148, 152-161.

3. Budiarso IT, Rikihisa Y. Vascular lesions in lungs of Bali cattle with Jembrana disease. Vet Pathol. 1992;29(3):210-215.

4. Davidson AJ, Eberle R, Ehlers B, et al. The order Herpesvirales . Arch Virol. 2009;154:171-177.

5. Foster AP, Twomey DF, Monie OR, et al. Diagnostic exercise: generalized alopecia and mural folliculitis in a goat. Vet Pathol. 2010;47 (4):760-763.

6. Jacobsen B, Thies K, Von Altrock A, et al. Malignant catarrhal fever-like lesions associated with ovine herpesvirus-2 infection in three goats. Vet Microbiol. 2007;124:353-357.

7. King AMQ, Lefkowitz E, Adams MJ, Carstens EB, eds. Virus Taxonomy: Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. London, UK: Elsevier/Academic Press; 2011:119-120.

8. Li H, Cunha CW, Taus NS. Malignant catarrhal fever: understanding molecular diagnostics in context of epidemiology. Int J Mol Sci. 2011;12:6881-6893.

9. Li H, Keller J, Knowles DP, et al. Transmission of caprine herpesvirus 2 in domestic goats. Vet Microbiol. 2005;107:23-29.

10. Li H, O'Toole D, Kim O, et al. Malignant catarrhal fever-like disease in sheep after intranasal inoculation with ovine herpesvirus-2. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2005;17:171-175.

11. Li H, Keller J, Knowles DP, et al. Recognition of another member of the malignant catarrhal fever virus group: an endemic gammaherpesvirus in domestic goats. J Gen Virol. 2001;82:227:232.

12. Maxie MG, Robinson WF. Cardiovascular system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol. 3. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2007:69-72.

13. Russell GC, Stewart JP, Haig DM. Malignant catarrhal fever: A review. Vet J. 2009;179(3):324-335.

14. Twomey DF, Campbell I, Cranwell MP, et al.Multisystemic necrotising vasculitis in a pygmy goat (Capra hircus). Vet Rec. 2006;158:867-869.

15. Zachary JF. Mechanisms of microbial infections. In: Zachary JF, McGavin MD, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St Louis, Missouri: Mosby Elsevier; 2012:219.