WSC Conference 7, Case 1

Signalment:

9-year-old, male neutered mixed breed dog, canine (Canis familiaris)

History:

This patient developed skin nodules primarily affecting the distal forelimbs. The nodules were pruritic, alopecic, and erythematous, with minimal hemorrhagic exudate. Prior treatments included antibiotics, ivermectin, and lime sulfur dips.

The patient is a raccoon hunting dog who lives in an outdoor kennel with a concrete floor and no bedding. The dog has not traveled since the lesions began. Approximately 6 months after the nodules developed, multiple punch biopsies were collected from the right elbow and metacarpus and submitted for examination.

Laboratory Results:

A deep skin scraping revealed suspected larval nematodes as well as inflammatory cells and mixed bacteria.

A bacterial culture of the skin grew Staphylococcus pseudintermedius.

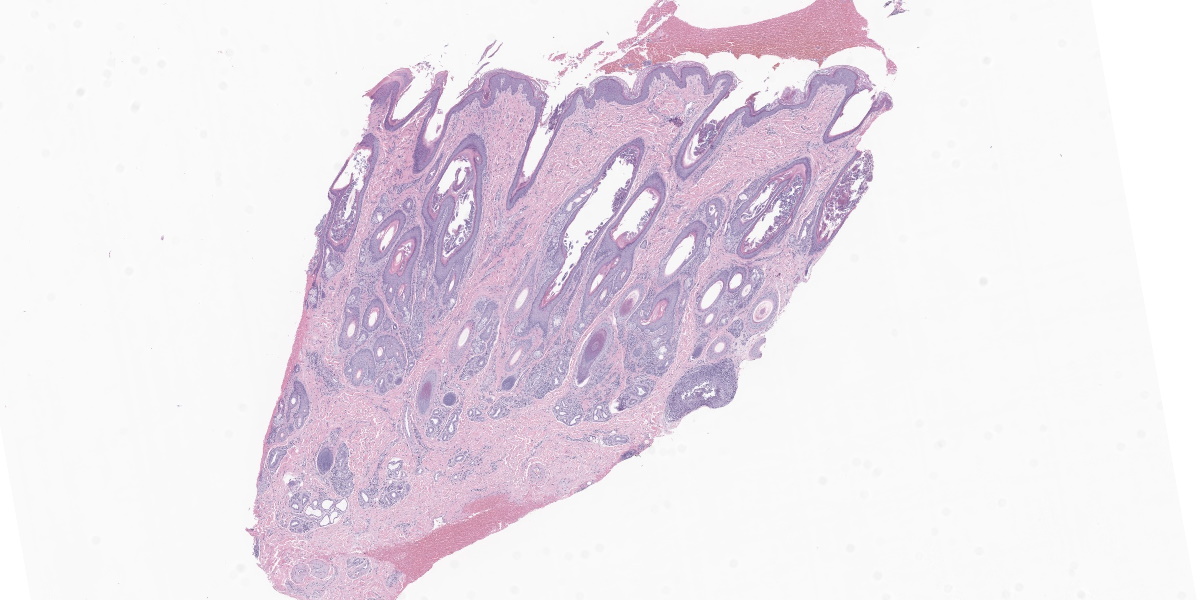

Microscopic Description:

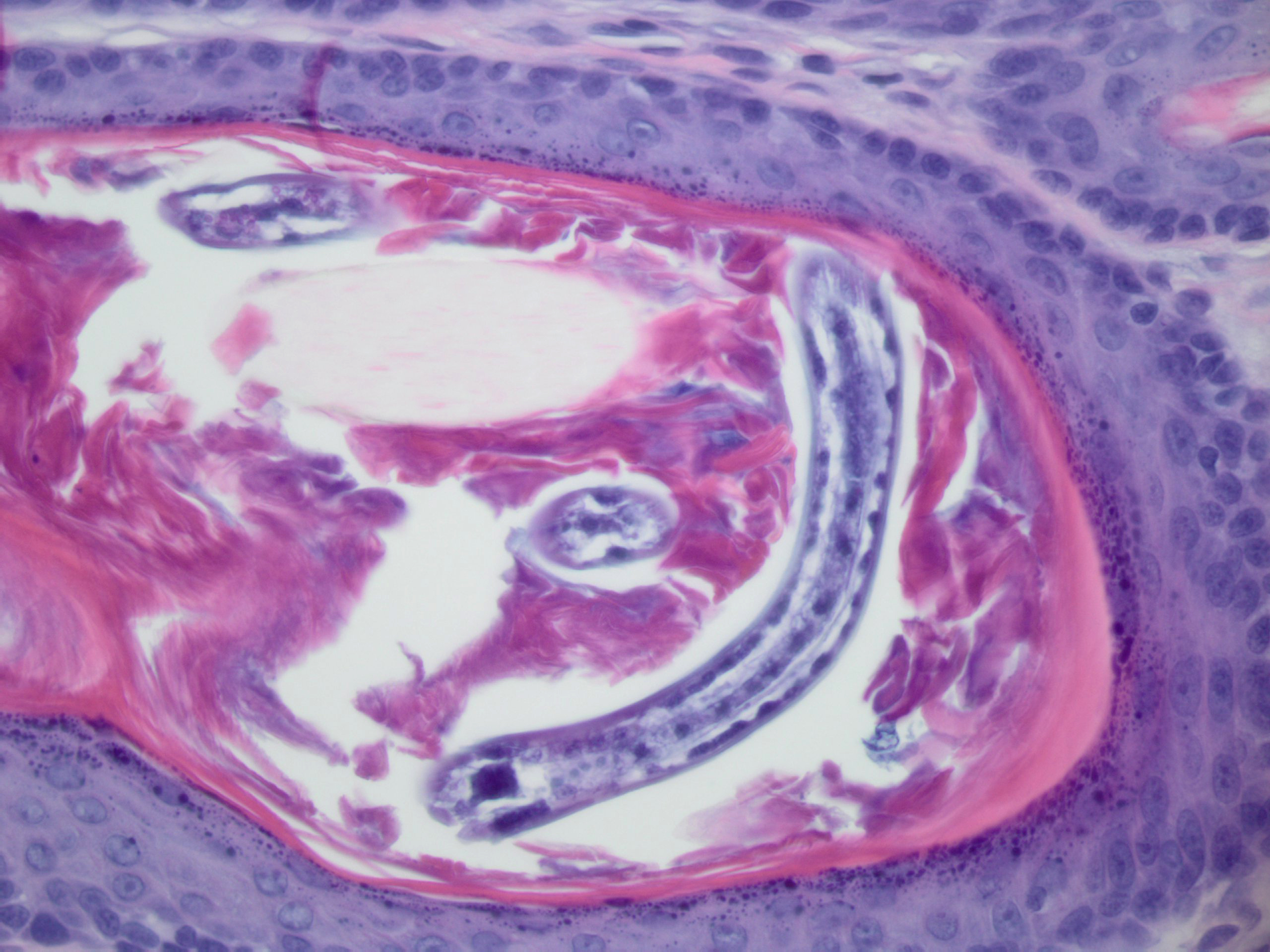

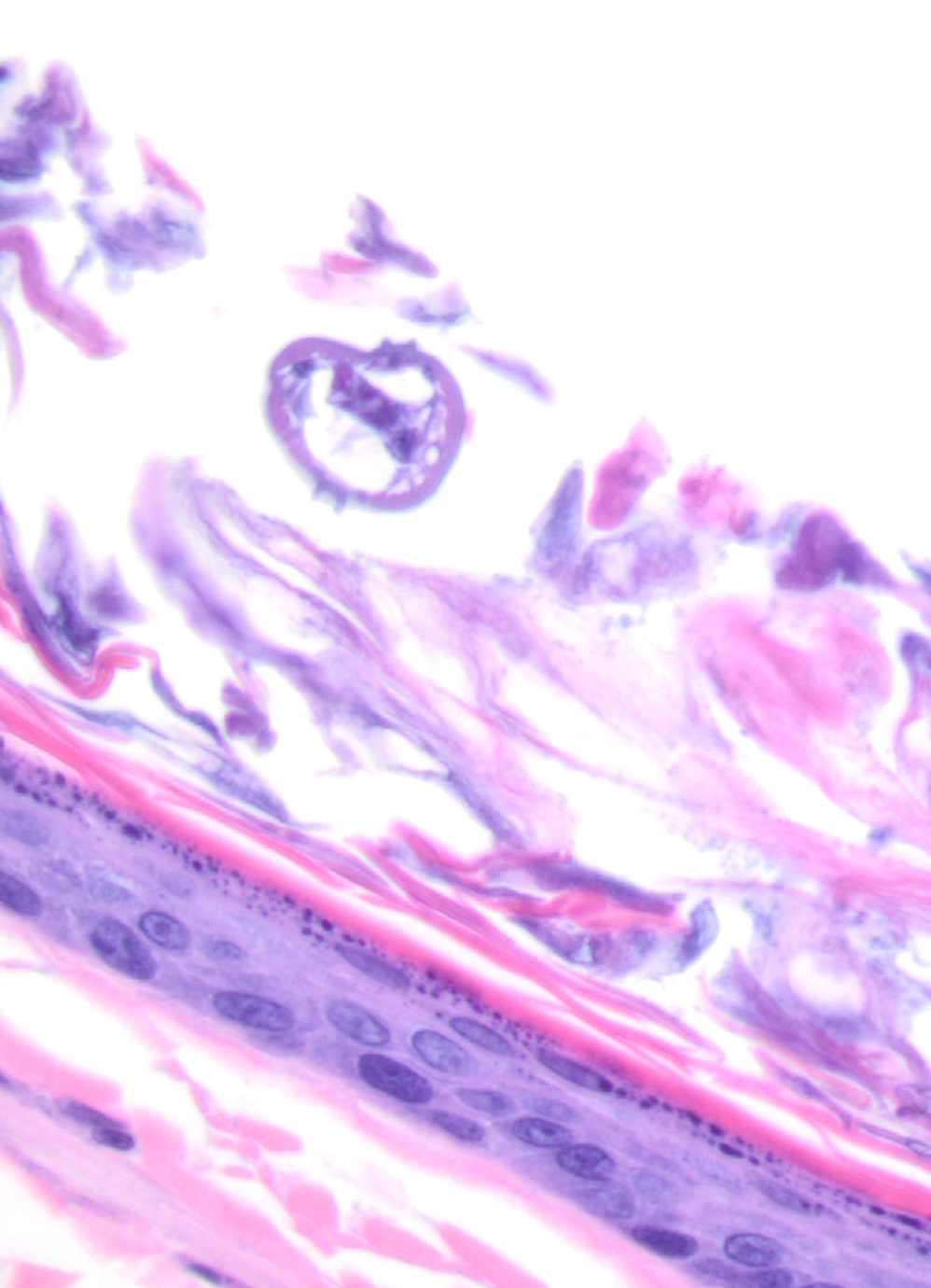

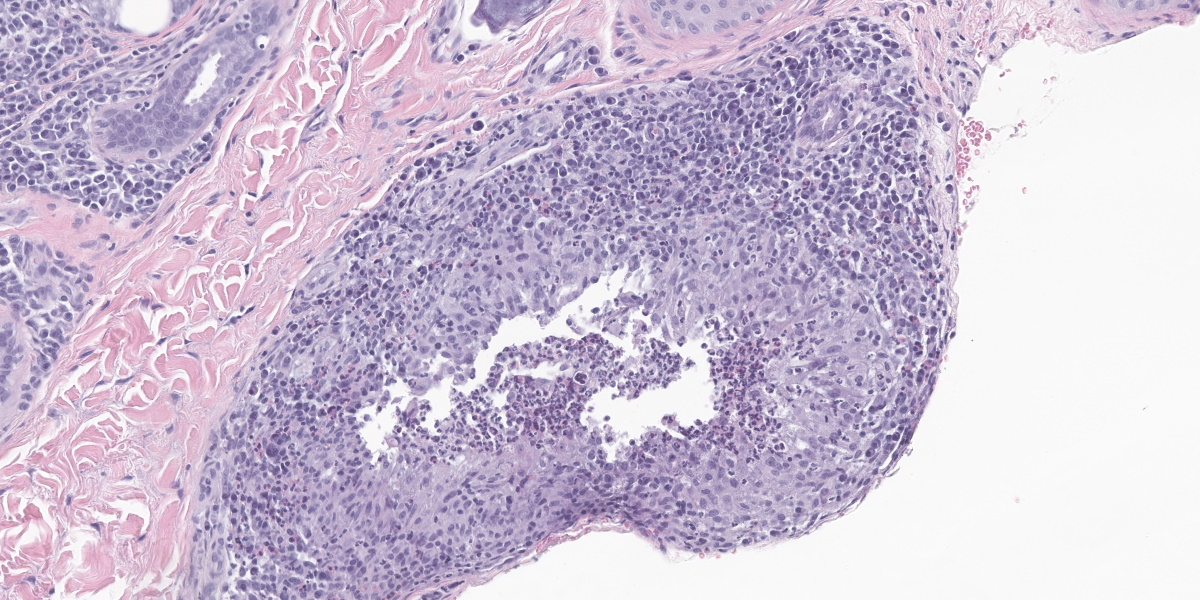

Diffusely, follicles are large and distended with keratin and occasional nematode larvae that are 20-30 microns in diameter with double lateral alae and a rhabditiform esophagus.

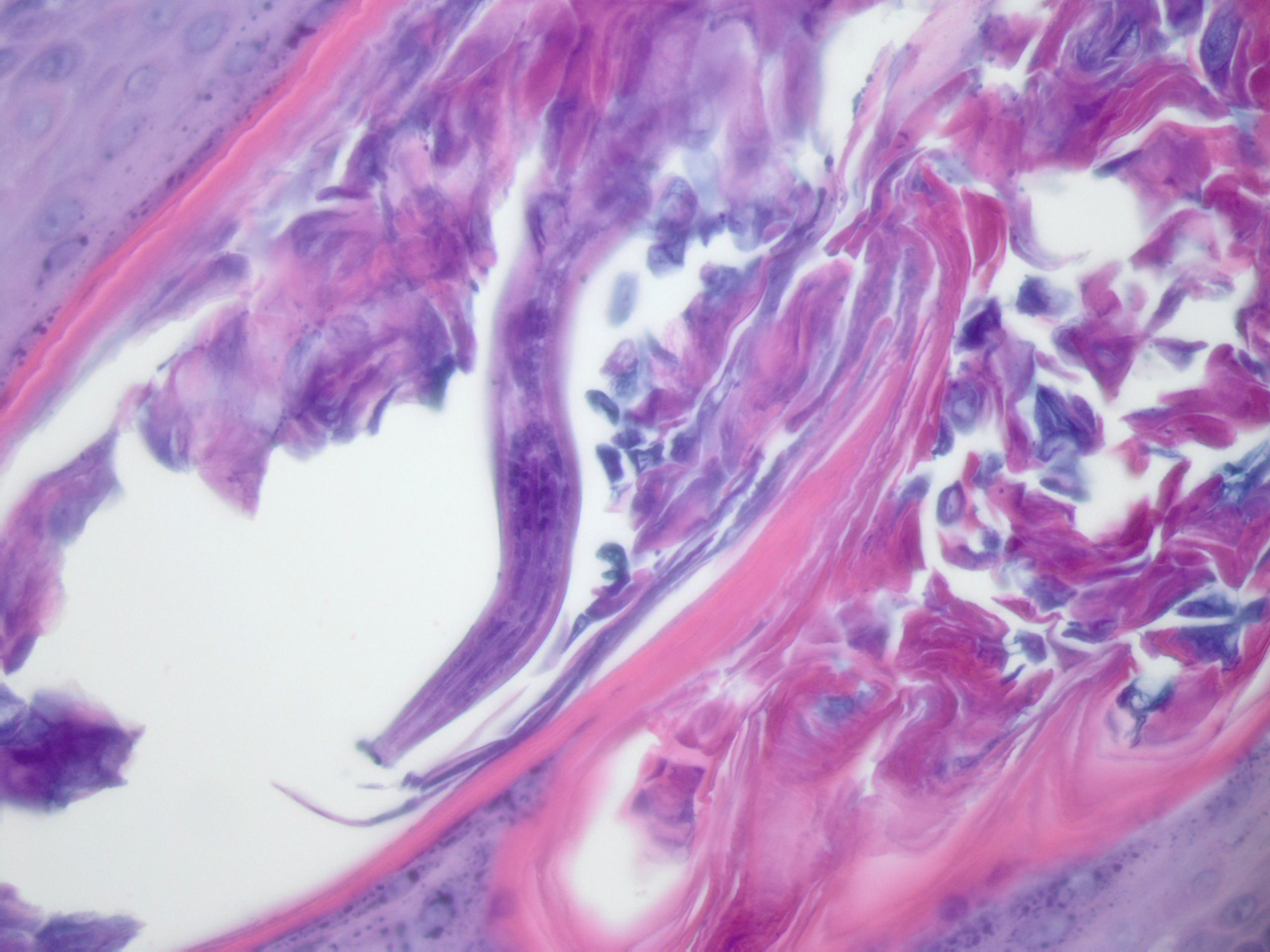

There is hyperplasia of the follicular epithelium. Adnexa are surrounded by plasma cells and fewer lymphocytes. There are multifocal aggregates of macrophages, neutrophils, and eosinophils with fewer multinucleated giant cells which tend to be at the base of follicles. In some sections, this inflammation is associated with follicular rupture with release of free keratin, and presumably nematodes, into the periadnexal dermis. There are varying degrees of hemorrhage and fibrosis around the ruptured follicles. Some follicles also contain bacterial cocci. There is diffuse mild epidermal hyperplasia with ortho-keratotic hyperkeratosis.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Haired skin: Widespread periadnexal plas-macytic dermatitis with intrafollicular larval nematodes and multifocal follicular rupture with pyogranulomatous dermatitis.

Contributor’s Comment:

The clinical, cytologic, and histologic findings are consistent with follicular Pelodera strongyloides infection. P. strongyloides is a free-living rhabditid nematode that lives in decaying organic matter. Infections are rare, and most infections in the United States have been reported in the Midwestern states.5 Infections are often associated with dirty environments or the use of damp straw for bedding.1,5 Cattle, swine, dogs, horses, rodents, sheep, and humans are infected by exposure to infested organic matter.1,2,5 Lesions occur at sites of contact with contaminated materials, which, in dogs, are primarily the ventrum, paws, distal limbs, perineum, and tail. Short-coated dogs may be more easily parasitized.5 Removal of the animal from infected bedding may clear the infection, although treatment with anti-parasitics is also warranted.6 Fittingly, this dog is a short-haired hound dog mix whose lesions were primarily on the distal forelimbs.

Clinically, an erythematous maculopapular rash with variable alopecia is reported. The lesions are extremely pruritic, so there may be associated self-trauma.5 Histologically, there is epidermal hyperplasia with hyperkeratosis and follicular keratosis. The nematodes can be found in hair follicles and in the superficial keratin.5 Follicular nematode larvae can penetrate the follicular infundibula, inciting folliculitis that can progress to furunculosis and pyogranulomatous dermatitis.2 Adnexa are surrounded by mixed inflammatory cells, including eosinophils, lymphocytes, plasma cells, macrophages, and mast cells.5

The nematodes are recognized by their small size, double (or paired) lateral alae, rhabditiform esophagus, platymyarian musculature, and intestine lined by uninucleated cells.3,4 Given the small size of these nematodes, identification of some of these structures on histologic examination is challenging.

Lesions in this dog initially persisted despite appropriate antibiotic therapy, cleaning the environment, and ivermectin treatment. Lesions eventually improved and skin scrapes were negative following treatment with the antibiotic Simplicef (cefpodoxime proxetil)

and the broad-spectrum anti-parasitic Advantage Multi (imidacloprid and moxidectin).

A complete blood count identified consistent leukopenia of unknown cause, so concurrent immunosuppression may have contributed to the infection and delayed response to treatment.

Contributing Institution:

University of Tennessee

College of Veterinary Medicine

Dept. of Biomedical and Biological Sciences

http://www.vet.utk.edu/departments/path/index.php

JPC Diagnosis:

Haired skin: Dermatitis and folliculitis, lymphoplasmacytic, moderate, with furunculosis and numerous intrafollicular nematode larvae and adults.

JPC Comment:

Pelodera is an uncommon cause of canine dermatitis that receives only rare mention in veterinary literature. The contributor provides an excellent summary of this condition.

One of the main differentials for canine Pelodera dermatitis is hookworm dermatitis caused by Ancylostoma caninum, Ancylostoma braziliense, Ancylostoma ceylanicum, or Uncinaria stenocephala.7 Similar to Pelodera dermatitis, hookworm dermatitis occurs on areas of the body in frequent contact with the ground, including the distal limbs and feet, ventrum, and tail. The third-stage hookworm larvae that invade the skin are generally not host-specific, leading to possible cutaneous larval migrans in many aberrant hosts, such as humans.7 Clinical signs can include secondary pyoderma and paronychia and epidermal hyperplasia; histologic lesions include eosinophilic, neutrophilic, and histiocytic perivascular dermatitis with degenerate leukocytes lining cutaneous migration paths.7 In addition to Pelodera, Ancylostoma, and Uncinaria, other helminth genera that can cause cutaneous larval migrans include Necator, Strongyloides, Gnathostoma, and Bunostoma.7

The week’s conference was moderated by Dr. Charles Bradley, Assistant Professor of Pathobiology at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine. Dr. Bradley discussed several cutaneous nematodiases in various species. Examples included Onchocerca cervicalis, associated with equine bursitis (delightfully named “fistulous withers” and “poll evil,” depending on location), and the ventral midline filarial dermatitis caused by Stephanofilaria stilesi in cattle. In the cutaneous nematode universe, however, only Pelodera invades the hair follicle and causes folliculitis and furunculosis, making for a straight-forward, if uncommon, diagnosis.

Dr. Bradley also discussed carefully curating morphologic diagnoses by including only histologic features essential to the diagnosis; histologic features that are nonspecific, incidental, or not prominent are better left to the description. To that end, the JPC morphologic diagnosis was ruthlessly pruned to highlight the essentials of this condition: the intrafollicular parasites and associated follicular inflammation.

References:

- Bowman DD. Helminths. In: Bowman DD, ed. Georgi’s Parasitology for Veterinarians. 10th ed. Elsevier; 2014:191-194.

- Capitan RGM, Noli C. Trichoscopic diagnosis of cutaneous Pelodera strongyloides infestation in a dog. Vet Dermatol. 2017;28(4):413-e100.

- Eberhard ML. Histopathologic Diagnosis. In: Bowman DD, ed. Georgi’s Parasitology for Veterinarians. 10th ed. Elsevier;2014:418.

- Gardiner CH, Poynton SL. Morphologic characterization of nematodes in tissue sections. In: An Atlas of Metazoan Parasites in Animal Tissues. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology;2006:14-15.

- Gross TL. Pustular and nodular disease with adnexal destruction. In: Skin Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 2nd ed. Blackwell;2005:449-450.

- Mauldin EA, Peters-Kennedy J. Integumentary System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Vol 1. Elsevier; 2016:689.

- Welle MM, Linder KE. The Integument. In: Zachary JF, ed. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 7th ed. Elsevier; 2022:1238.