Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2018-2019

Conference 22

5 April, 2019

CASE IV: (JPC 4103280 )

Signalment: 10Y, male intact, Whippet, Canis lupus familiaris, dog

History: The dog had a history of hyperadrenocorticism due to a functional pituitary adenoma and a urinary tract infection, from which Streptococcus canis was isolated. Additionally, the dog showed mild intermittent nasal discharge over the past few months. Suddenly the dog developed severe dyspnea and generalized weakness, after which it was referred to the clinician and treated with antibiotic and anticoagulant therapy. The dog died shortly thereafter.

Gross Pathology: The right side of the lung was severely enlarged, firm and dark red with a 2 cm long thrombus within a large branch of the arteria pulmonalis. Both adrenals were enlarged. The trunk muscles were mildly atrophied and the skin of the abdomen was thin and of increased fragility. Besides those changes attributed to the prolonged hyperadrenocorticism, the intestinal wall was diffusely thickened and red, with multifocal petechial hemorrhages on the serosa. Within the intestinal lumen, several different adult nematodes and myriad, 2-4 mm long adult cestodes were found.

Laboratory results: Laboratory Results (clinical pathology, microbiology, PCR, ELISA, etc.):

A parasitological examination of the intestinal contents was performed:

1) Flotation: Hookworm eggs +++, Taenidae eggs +++, Toxocara sp. Eggs +++, Capillaria sp. Eggs +

2) Parasite identification of proglottids using PCR: Positive for Echinococcus multilocularis

Microscopic Description:

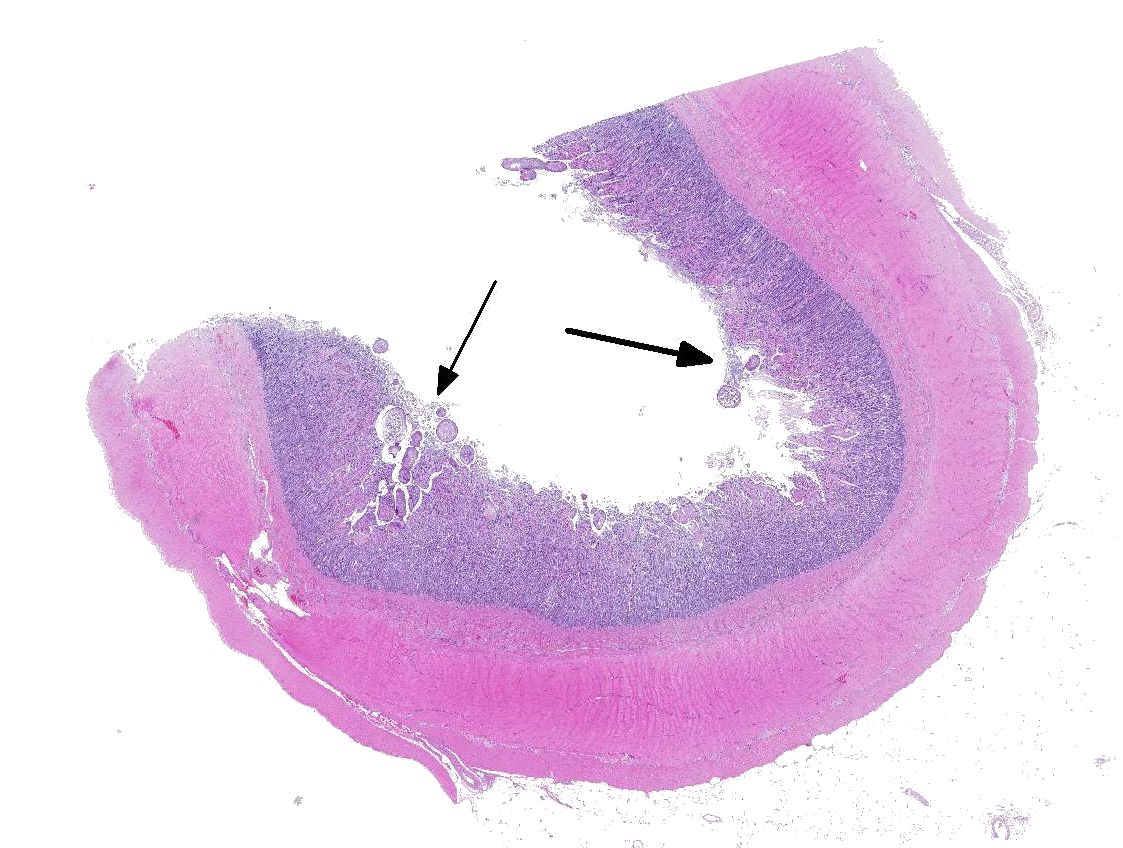

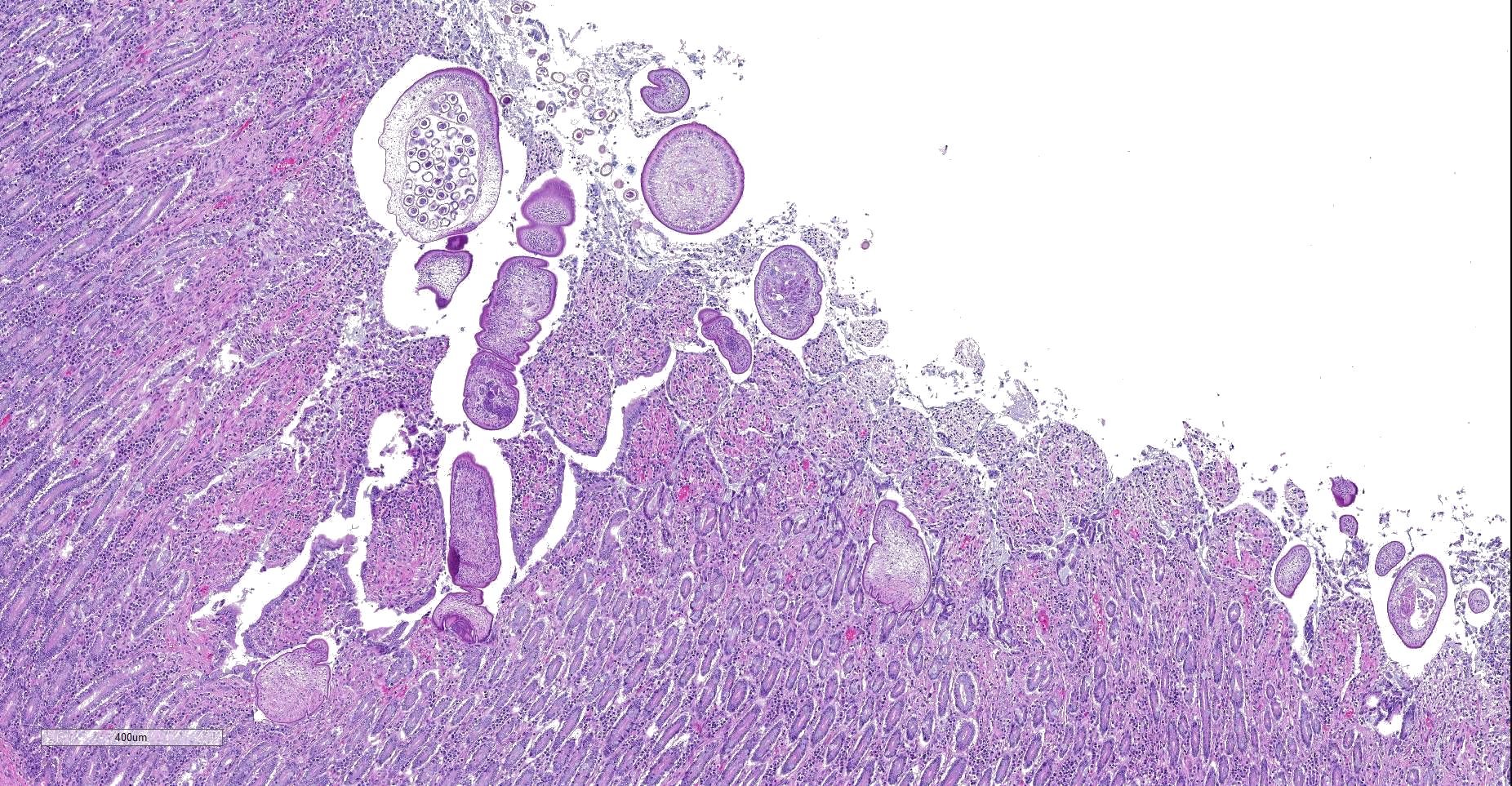

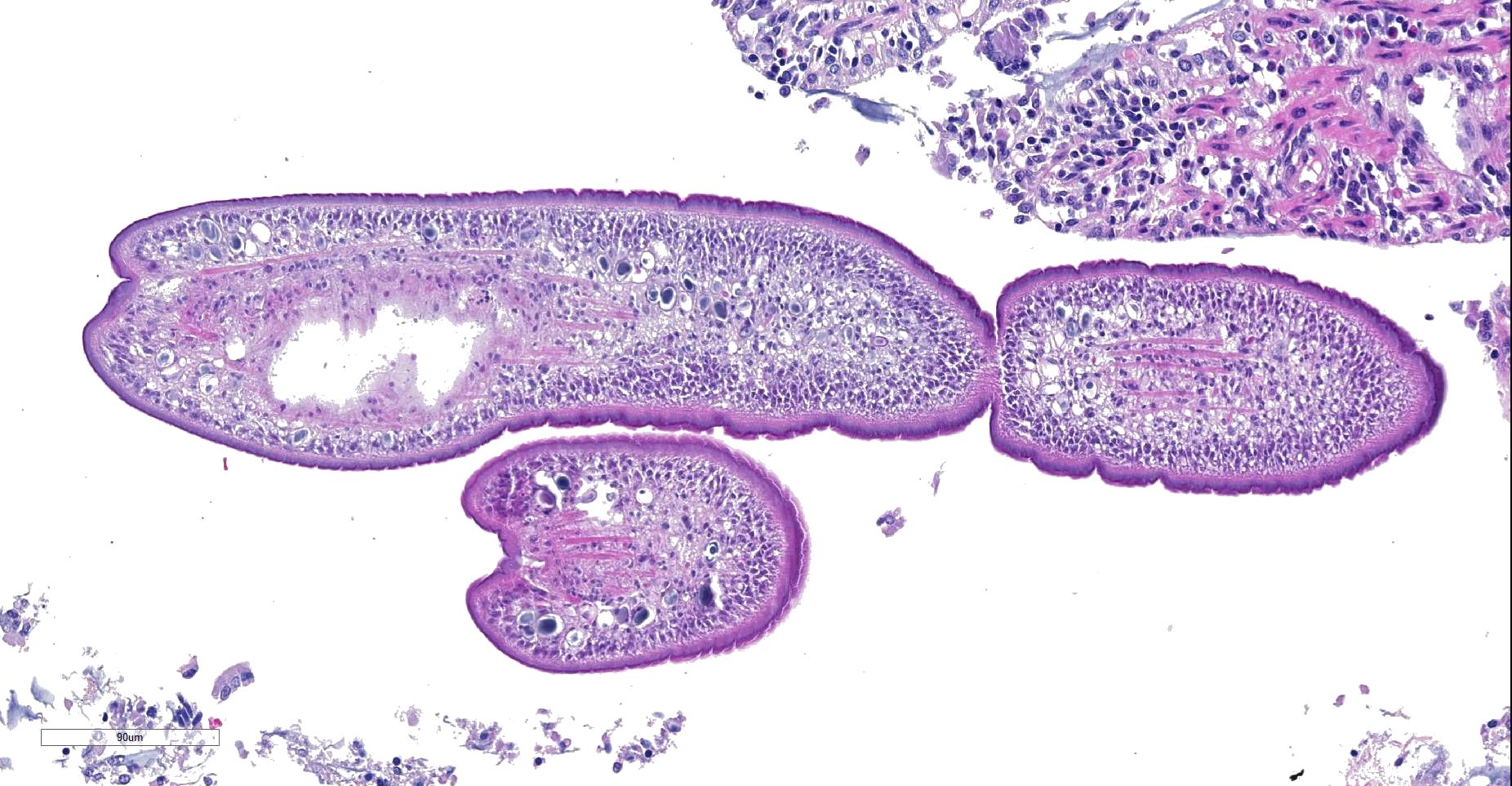

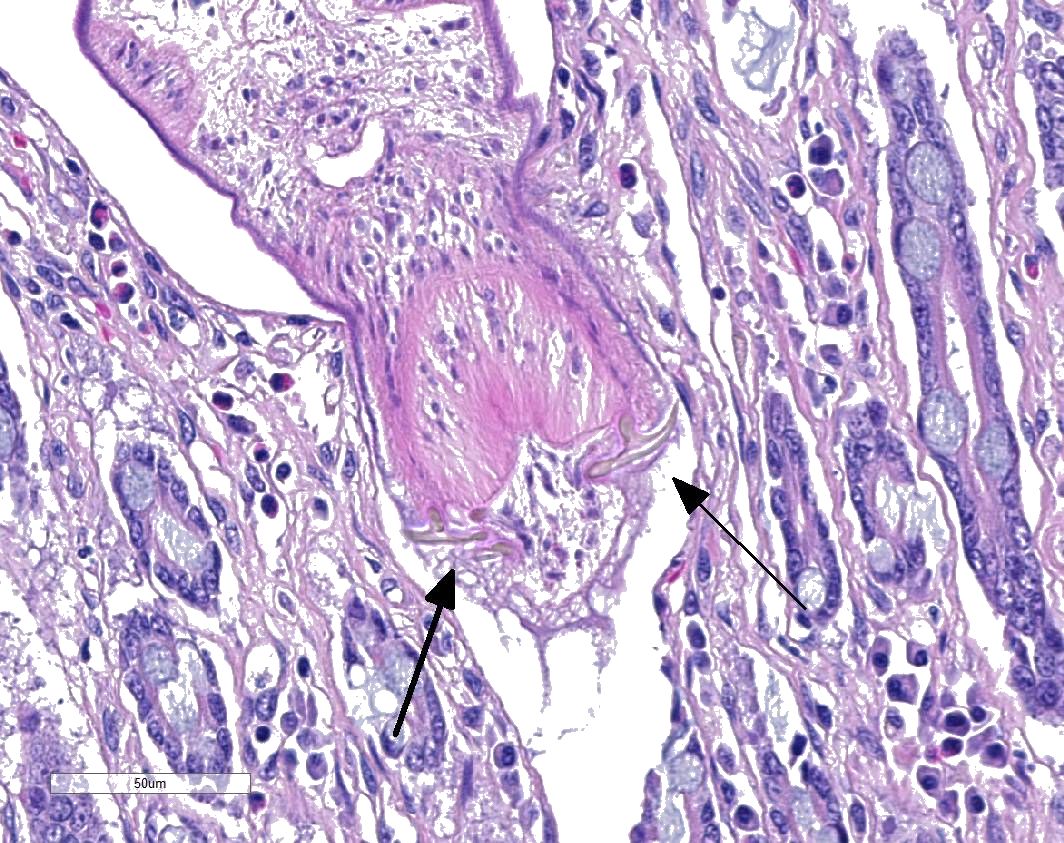

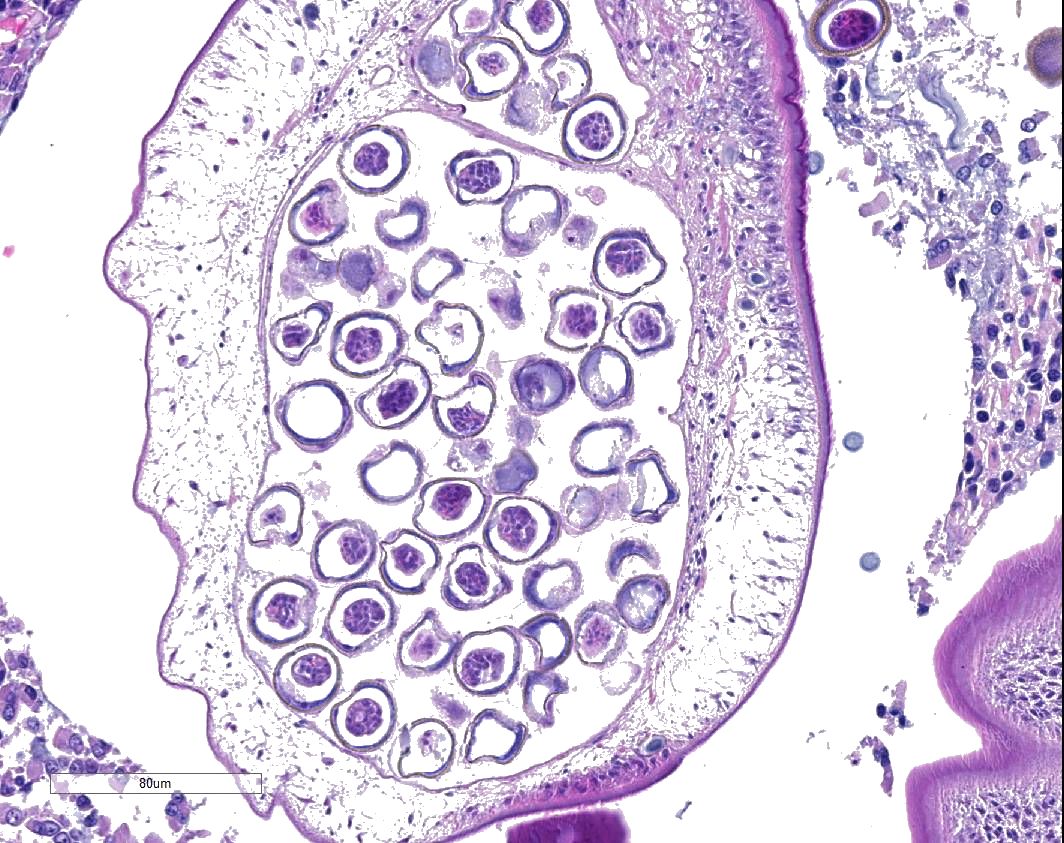

Dog, small intestine: Multifocally, within the intestinal lumen and within the mucosa, there are several cross and longitudinal sections of adult cestode parasites of about 100-300 µm in diameter and up to 500 µm in length, with 3-5 well visible segments (proglottids). The first segment (scolex) has multiple short hooks (may not be present on all slides) attached between intestinal villi or deep into the crypts of Lieberkühn. The parasites are covered with a 3-5 µm thick amphophilic tegument with supporting basement membrane, under which there are two zones of non-striated circular (inner) and longitudinal (outer) muscle layers. Multifocally within the parasitic body parenchyma there are few round to oval, dark basophilic, granular structures of about 10 to 15 µm in diameter (calcareous bodies). Within the mature proglottid there are numerous multilobulated, round to oval, around 30 µm in diameter large basophilic structures (testes). The most posterior, bell-shaped segment contains an egg-filled uterus (gravid proglottid). The eggs, also present freely in the intestinal lumen, are round or spherical and up to 30 µm in dimeter, with a radially striated, brown embryophore. The egg lumen is filed with round to oval, up to 30 µm in diameter large onchosperes (embryonated eggs). The lamina propria and submucosa are infiltrated by a moderate amount of plasma cells, lymphocytes and few eosinophils, and multifocally there is mild fibroblast proliferation (fibrosis). Multifocally, the intestinal crypts are dilated and filled with degenerated and viable neutrophils.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Dog, small intestine: Moderate, multifocal-coalescing, subacute, lymphoplasmacytic Enteritis with intralesional adult cestodes consistent with Echinococcus multilocularis

Contributor’s Comment: The necropsy of the dog revealed pulmonary thrombosis as the cause of death. This was attributed to the hypercoagulability, known to be associated with hyperadrenocorticism. During necropsy, we surprisingly observed that the intestinal lumen contained large number of small, white, segmented tapeworms. Parasitological and histological investigation subsequently confirmed a severe intestinal infestation with Echinococcus multilocularis.

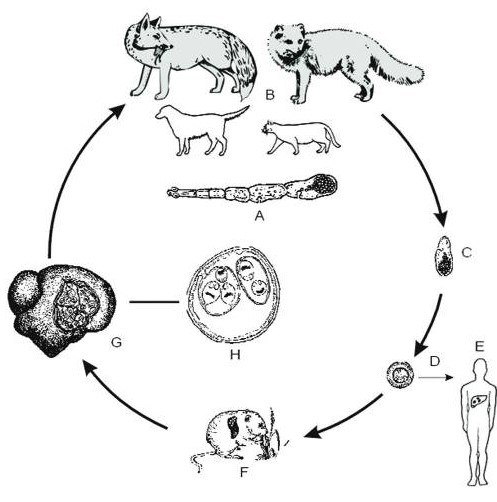

There are two major Echinococcus species of special importance to veterinary medicine, namely E. multilocularis and E. granulosus. E. multilocularis is a zoonotic cestode present in large parts of the northern hemisphere.11 Transmission of E. multilocularis occurs in a sylvatic cycle, which is sometimes linked via infected small mammals to domestic dogs and cats.4 (Figure 1)

Taken from: Eckert J, Deplazes P. Biological, epidemiological, and clinical aspects of echinococcosis, a zoonosis of increasing concern. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004

E. multilocularis tapeworms may be present in the small intestine of a number of species of carnivores, but predominantly affects canids.7 In Europe, a high prevalence (23.9–57.3%) of E. multilocularishas been frequently reported in the red fox population (Vulpes vulpes)3,10,11 which is increasingly colonizing urban areas. In domestic dogs, however, this infection is rare. In a study performed in Lithuania in 2009, the prevalence within a group of 240 tested dogs was 0.8%.2 Similarly, in Switzerland, echinococcosis is sporadic and most cases are diagnosed in wildlife.

Intestinal infestations of E. multilocularis in the definitive host usually cause little to no clinical symptoms or pathomorphological lesions. A far more severe form of infection with this parasite is alveolar echinococcosis (AE). Among the many species (>40 species) of small mammals that are susceptible to E. multilocularis under natural conditions, members of the family Arvicolidae (voles and lemmings) and Cricetidae (hamsters, gerbils, and related rodents) are most important. Aberrant host animals and humans can also become infected with the metacestode stage, which has the potential to cause AE, one of the most lethal helminthic infection in humans.5 Relatively recently, domestic dogs have also been revealed to be aberrant intermediate hosts for AE.5 In the intermediate host, the oncosphere penetrates the intestinal wall and enters the blood system. Via the blood stream, the oncosphere reaches different organs, especially the liver. Once the oncosphere has reached the liver it starts to develop into the metacestode stage. A characteristic feature of this stage is its exogenous tumor-like proliferation, which leads to infiltration of the affected organs and, in progressive cases, to severe disease and even death.4

Although we regularly see AE in zoo animals, particularly in primates, this is the first case of intestinal echinococcosis diagnosed in a domestic dog at our Institute. The histologic slide shows several cross and longitudinal sections of well-preserved adults, which make for a great exercise in the histological descriptions of cestodes. The infestation and the development of pathological lesions within the intestine might have been exacerbated by the immunosuppressive effects of hyperadrenocorticism.

Contributing Institution:

Institute for Animal Pathology

Vetsuisse Faculty - University of Bern

122 Länggassstrasse

3001-CH Bern

Switzerland

www.itpa.vetsuisse.unibe.ch

JPC Diagnosis: Jejunum: Multiple embedded adult cestodes.

JPC Comment: The contributor has provided an excellent discussion of the life cycle and

pathobiology of this important and emerging zoonotic parasite in the Northern Hemisphere. While not an especially exciting descriptive exercise, this would be the first time that the adult cestode has been submitted to the WSC; five cases of the metacestode have been submitted including a dog (WSC 2015 Conf 1, Case 4) and a rhesus macaque (WSC 2011, Conf 18, Case 2).

From a comparative standpoint, two major forms of echinococcal disease occur in humans: cystic echinococcosis (prototypically caused by E. granulosus in 88% of cases, but also E. equinus, E ortleppi and E. canadensis), and alveolar echinococcosis (caused by E multilocularis, E. vogeli, and E. oligoarthrus).6 Echinococcosis is one of the 17 neglected tropical diseases recognized by the World Health Organization, ranked third as the most relevant food-borne parasitic zoonosis, and affects 18,000 people each year, with most cases seen in Asia and Europe, with 91% of cases seen in China.9

In humans, AE is characterized by a long asymptomatic incubation period up to 15 years. Metacestodes of E. multilocularis generally develop in the right lobe of the liver, growing from initial lesions of several mm to large multilocular lesions ranging over 20cm in diameter. 1Lesions in other organs arise as a result of infiltration or metastasis. Symptoms in the chronic course include jaundice, abdominal pain, fatigue and weight loss. Diagnosis of AE (based on imaging findings) has been standardized by the WHO in a PNM system (P denoting the size f the primary hepatic lesion, N the involvement of neighboring) organs, and M, the presence of metastatic lesions.) Treatment is anchored by radical resection (following principles of tumor surgery to diminish the possibility of leaving parasite residue), and the administration of benzimidazoles, such as albendazole. 1

References:

- Brunetti E, Kern P, Vuitton DA. Expert consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans. Acta Tropica 2010; 114:1-16.

- Bruinskait? R, Šark?nas M, Torgerson PR, Mathis A, Deplazes P. Echinococcosis in pigs and intestinal infection with Echinococcus spp. in dogs in southwestern Lithuania. Vet Parasitol. 2009;160:237–241.

- Bruzinskaite R, Marcinkute A, Strupas K, et al. Alveolar echinococcosis, Lithuania. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1618–1619.

- Eckert J, Deplazes P. Biological, epidemiological, and clinical aspects of echinococcosis, a zoonosis of increasing concern. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17:107–135.

- Frey CF, Marreros N, Renneker S, et al. Dogs as victims of their own worms: Serodiagnosis of canine alveolar echinococcosis. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:422.

- Higuita NIA, Brunetti E, McCloskey C. Cystic echinococcosis. J Clin Microbiol 2015; 54(3)518-523.

- Hofer S, Gloor S, Mu U, et al. High prevalence of Echinococcus multilocularis in urban red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) and voles (Arvicola terrestris) in the city of Zürich, Switzerland. Parasitology. 2000;120:135-142.

- Malczewski A, Gawor J, Malczewska M. Infection of red foxes (Vulpes vulpes) with Echinococcus multilocularis during the years 2001–2004 in Poland. Parasitol Res. 2008;103:501–505.

- Massolo A, Liccioli S, Budke C, Klein. Echinococcus multilocularis in North America: the great unknown. Parasite 2014; 21:73.

- Maxie MG, Cullen JM, Stalker MJ. Liver and Biliary System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO; 2016:319-320.

- Otero-Abad B, Rüegg SR, Hegglin D, Deplazes P, Torgerson PR. Mathematical modelling of Echinococcus multilocularis abundance in foxes in Zurich, Switzerland. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:21.