CASE III: N15-0245 (JPC 5147505)

Signalment:

15-year-old Hereford bull (Bos taurus taurus).

History:

The bull presented to the referring veterinarian (rDVM) for a swollen left eyelid and a mass ventral to the left ear. On presentation, there was marked corneal edema and ulceration of the left eye, and areas of alopecia were noted on the ventral midline skin. Histopathology of the eyelid was consistent with squamous cell carcinoma. The bull was euthanized and a full necropsy was performed.

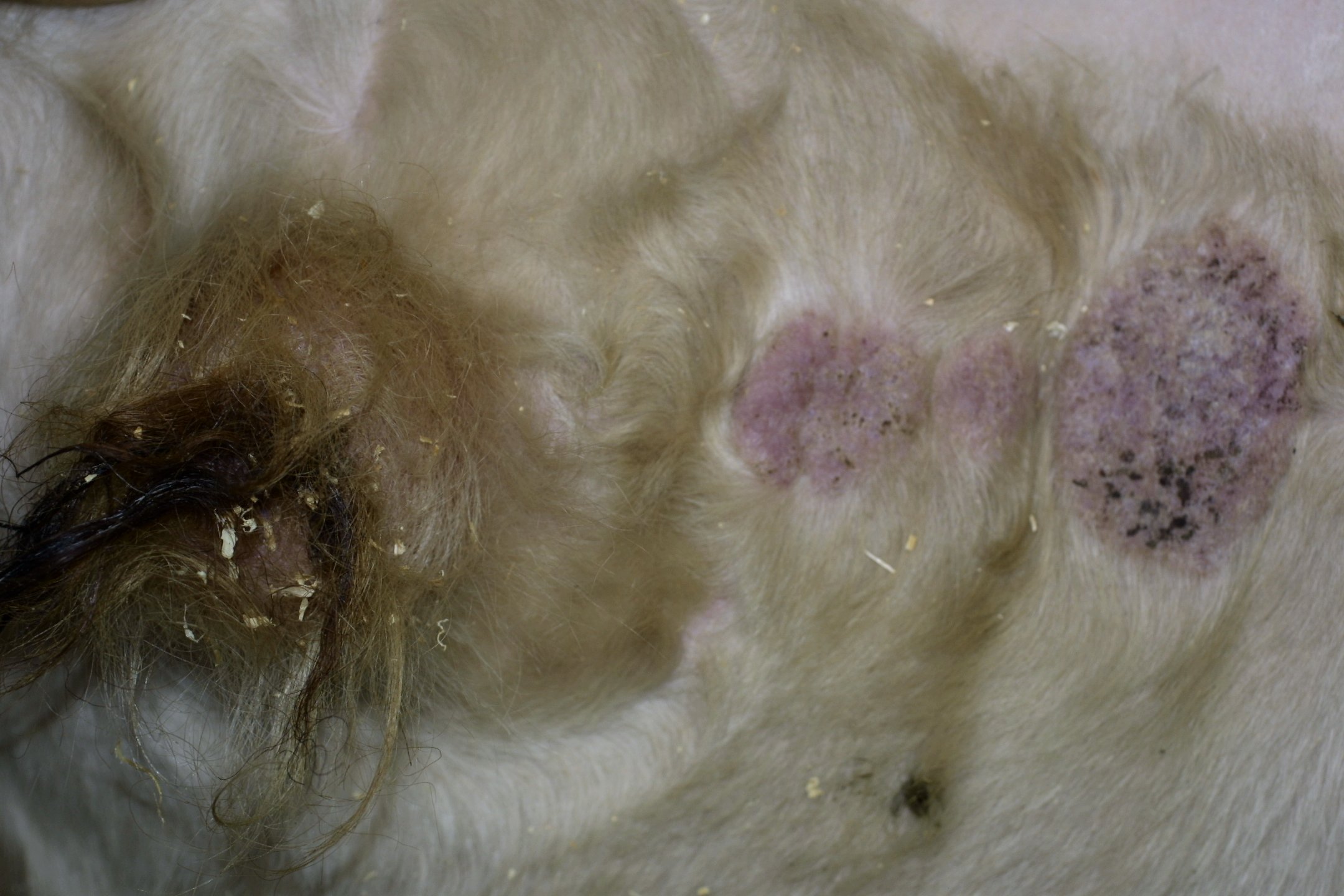

Gross Pathology:

At necropsy, multiple areas of circular, crusting alopecia were in a line along the ventral midline skin cranial to the prepuce. The largest lesion was 8cm in diameter and the smallest was 4cm. Additional gross lesions included squamous cell carcinoma of the left eye and enlarged mandibular lymph nodes.

Laboratory results:

Not applicable.

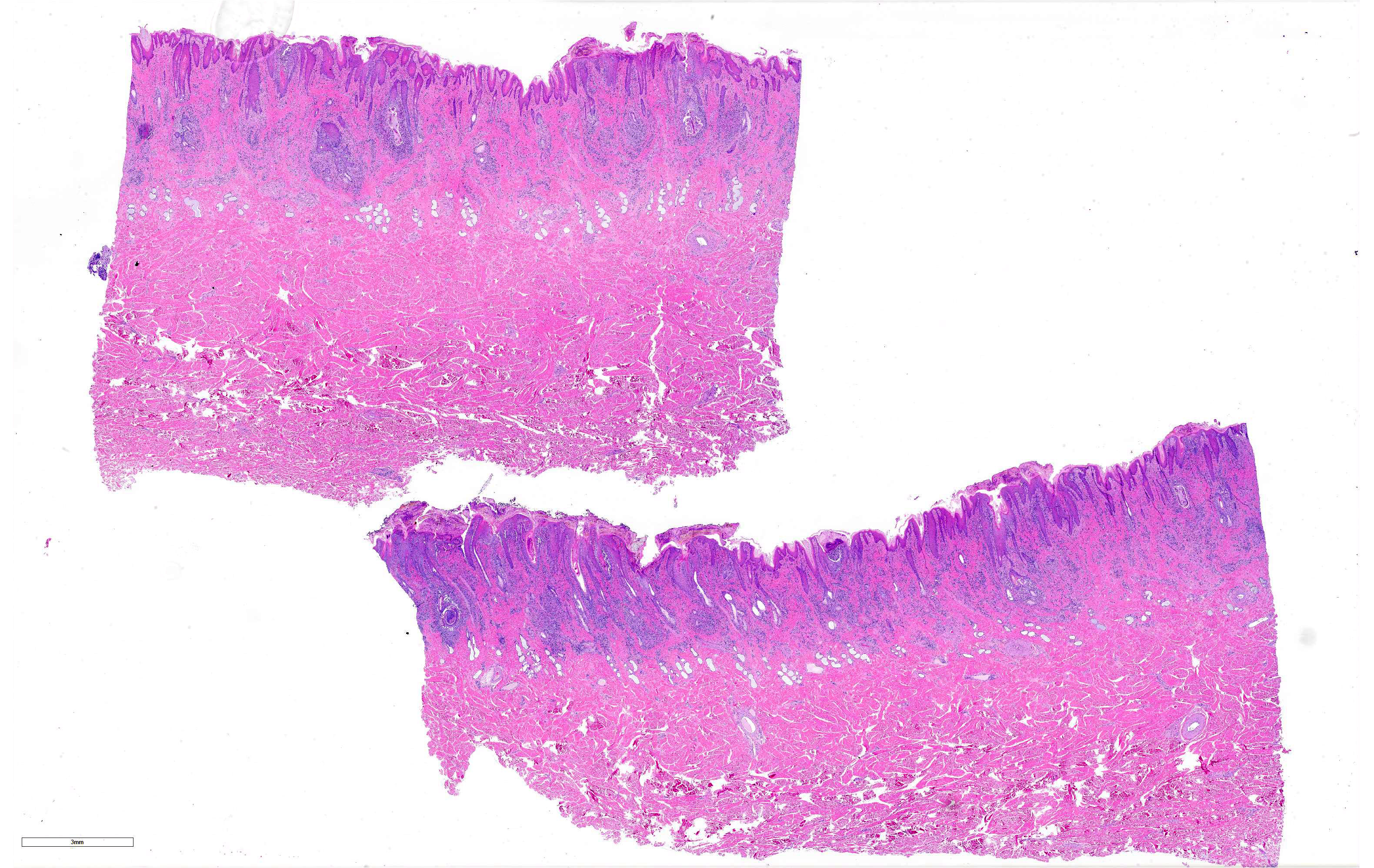

Microscopic Description:

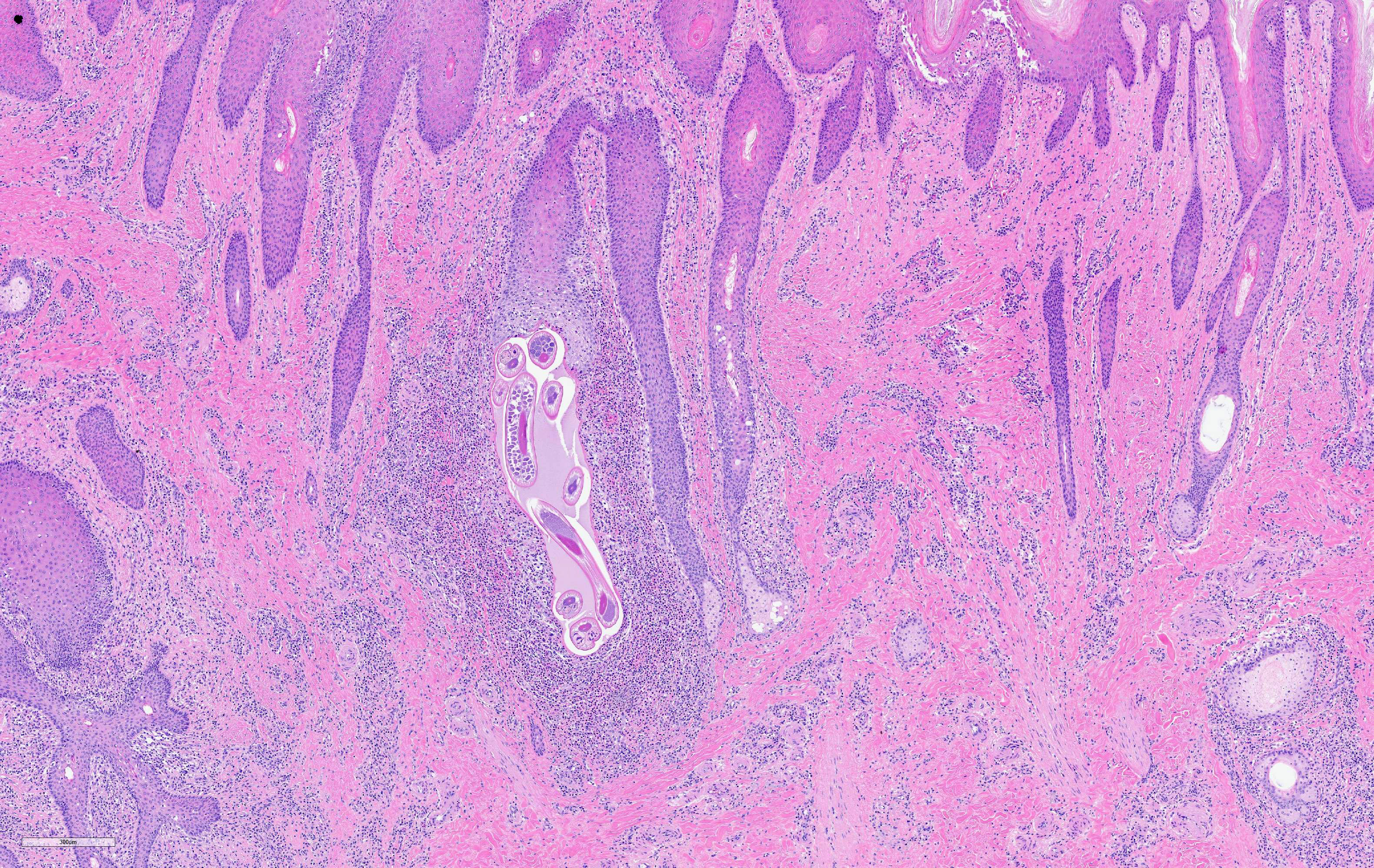

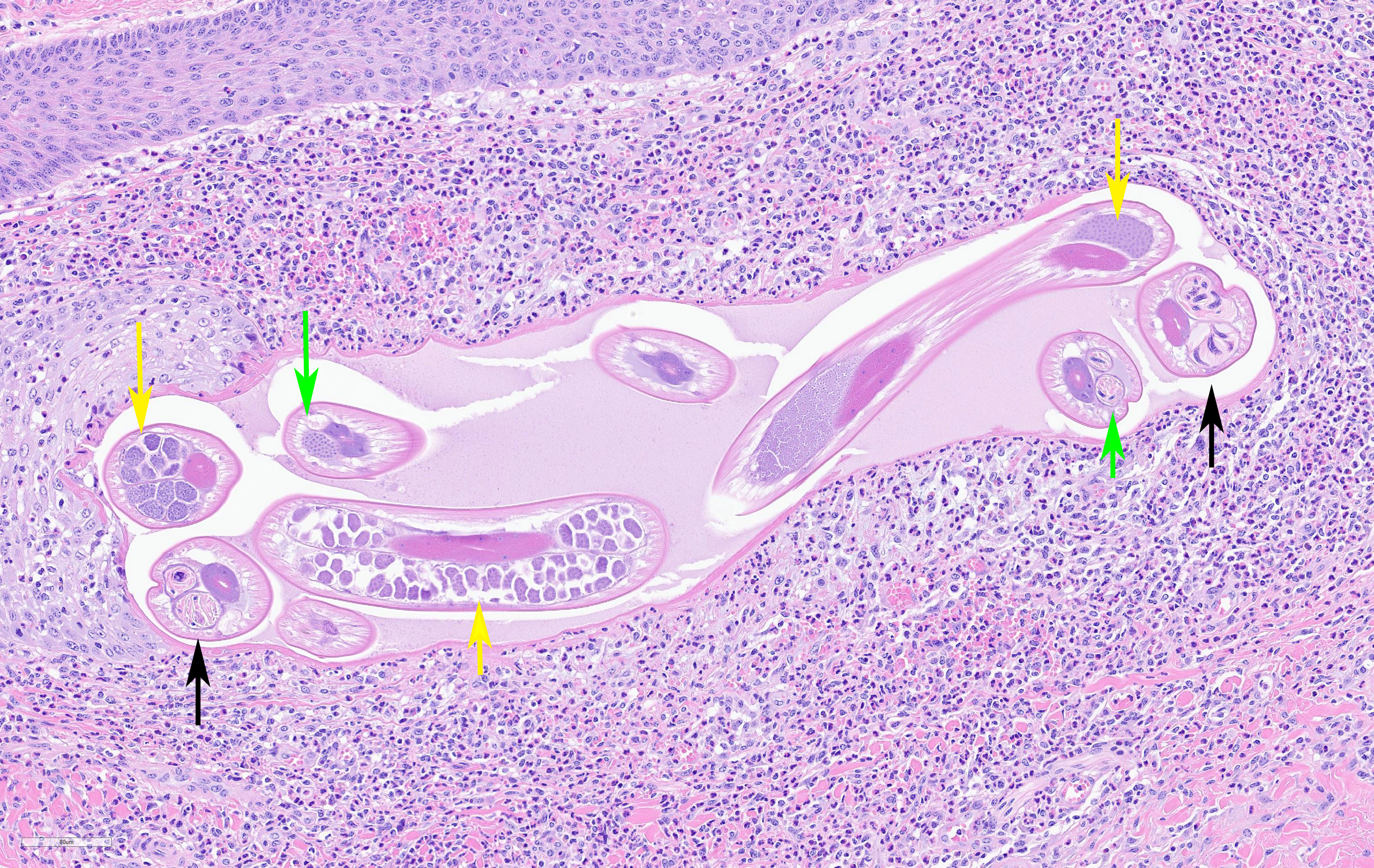

Two sections of haired skin from the ventral abdomen of the bull are submitted. There may be slide variation. Throughout the superficial and mid dermis centered around multifocal hair follicles and blood vessels, is an inflammatory infiltrate composed of numerous eosinophils and macrophages with fewer lymphocytes and plasma cells. Inflammation frequently surrounds sweat glands and diverticula at the hair follicle base that often contain cross-sections of 100 um in diameter adult, filariid nematodes that have a 5 um-thick, smooth cuticle, a pseudocoelom, polymyarian-coelomyarian musculature, lateral alae, prominent intestine, and either paired uteri containing microfilariae and eosinophilic discs or a testis. Occasionally, nematodes and necrotic debris are surrounded by multinucleate giant cells, and follicle diverticula are ruptured and replaced by similar inflammation and necrotic debris (furunculosis). There is mild, diffuse loss of adnexal glands, and hair follicles are frequently dilated with attenuated epithelium and abundant keratin, and occasional contain degenerate neutrophils and necrotic debris within the lumen or epithelium (folliculitis). Multifocally, the remaining apocrine glands are ectatic and there is increased connective tissue and small-caliber blood vessels (fibrosis). A few areas of hemorrhage, fibrin, and edema in the congested superficial dermis. The epidermis is moderately hyperplastic with formation of rete ridges, mild orthokeratotic and parakeratotic hyperkeratosis, spongiosis, and acanthosis. A few intracorneal pustules characterized by degenerate eosinophils, neutrophils and cellular debris embedded in proteinaceous fluid and containing rare nematodes and superficial bacteria are throughout the sections.

Contributor's Morphologic

Diagnosis:

Skin:

moderate, multifocal, chronic eosinophilic and histiocytic dermatitis, folliculitis,

and furunculosis with intralesional filarial nematodes (Stephanofilaria stilesi,

presumed).

Contributor's Comment:

While considered an incidental lesion in this case, stephanofilariasis is a common cause of dermatitis in cattle (particularly beef breeds) in the western and southwestern United States.5 The genus Stephanofilaria (Order Spirurida, Family Filariidae) encompasses several species of filariid nematodes that infect the skin of cattle and buffalo worldwide and are also found on goats, elephants, and rhinoceroses.4,5 Lesion distribution is often dependent on the feeding preference of the fly vector that transmits the parasite,4,5 with some species primarily causing lesions on the back (?hump-sore? of Zebu cattle; S. assamensis) or shoulder (S. dinniki in rhinoceroses), ears (S. zaheeri in buffalo), or feet (S. kaeli).4,5 Speciation can be difficult due to subtle differences between species, erroneous taxa,4 and a lack of comparative genomic analyses within the genus. In North America, the primary species is S. stilesi, which is transmitted by horn flies (Haematobia irritans) that ingest microfilariae and deposit infective larvae while feeding on the skin.5 The characteristic gross finding, as observed in this case, is development of singular or multiple alopecic and lichenified plaques along ventral midline.5 Similar lesions may also occur on the scrotum, flank, udder, or teats.5 Differential diagnoses for cutaneous nematodiasis in cattle would include infection with Rhabditis spp., Onchocerca spp., or rarely Pelodera spp.5

Histologically, adult S. stilesi reside in cystic diverticula off the base of hair follicles and microfilariae can be found on the skin surface enclosed in vitelline membranes, free within the dermis, or within lymphatic vessels.4,5 Inflammatory reaction to the adult nematodes is mild unless there is rupture of the cyst wall and spread to the dermis, where the cellular reaction is mainly eosinophilic or lymphocytic.4,5 Adult filariid nematodes are characterized by a thick cuticle, coelomyarian musculature, thick-walled intestine, lateral alae, and paired uteri containing microfilariae and eosinophilic discs in the female.2 S. stilesi infections can be differentiated from Pelodera spp. by the presence of microfilariae in the uteri, a prominent intestine, and absence of a rhabditiform esophagus.2,5 Rhabditis is another rhabditiform nematode genus that is most often associated with otitis externa in cattle and can exhibit matricidal hatching in which the larvae feed on the maternal tissues after developing in the uterus.1 Onchocerca spp. adults are not found in the hair follicles and the microfilariae are longer (200 μm vs. 50 μm) than S. stilesi.4,5 Stephanofilariasis is often mild, but if treatment is desired, the parasite can be killed effectively with ivermectin or topical organophosphates.5

Contributing Institution:

Texas A&M College of Veterinary Medicine (https://vtpb.tamu.edu/)

JPC Diagnosis:

Haired skin: Dermatitis, perifollicular, periadnexal and perivascular, eosinophilic and histiocytic, diffuse, moderate, with folliculitis, furunculosis, few intrafollicular adult filarid nematodes, and rare dermal microfilariae.

JPC Comment: The contributor provides a concise overview of the genus Stephanofilariae in addition to other etiologic agents that cause cutaneous nematodiasis in domestic and wildlife species.

As briefly mentioned by the contributor, rhinoceroses are one of the many species affected by this genus. Black rhinoceroses (Diceros bicornis) have been known to be infected by Stephanofilaria dinniki7, although a 2012 case report describing a filariosis outbreak in Meru National Park in Kenya described lesions consistent with the parasite in both black rhinoceroses and southern white rhinoceroses (Ceratotherium simum simum).6

Macroscopically, lesions were characterized by extensive cutaneous ulcerations with a 2-3cm depression and a mean diameter of 23 ±8cm in in white rhinoceroses. Similar lesions of black rhinoceroses but were smaller, measuring 15 ±5cm in diameter. Unfortunately nematodes were not observed in tissue samples obtained for histomorphologic examination; however, the authors attributed the filarid-like lesions to S. dinniki due to a striking resemblance to previously reported lesions caused by the parasite in addition to resolution following treatment with ivermectin.6

Although the lifecycle of S. dinniki is unknown, other species within the genus (such as S. stilesi) require a blood sucking arthropod vector, of which several species are commonly found on rhinoceroses and are thought to be involved in the parasite's transmission. In addition, a species of bird commonly observed in association with African megafauna, commonly known as oxpeckers, were also observed pecking at the lesions. The relationship between these large mammals and oxpeckers is usually classified as a "cleaning symbiosis" as each species benefits from the other under normal circumstances.

Although the act of oxpeckers feeding on necrotic skin is inherently traumatic, the authors suggest this may be beneficial from an epidemiological standpoint. This action likely disrupts the parasite's lifecycle by preventing arthropod vectors from ingesting microfilaria concentrated within the necrotic and infected cutaneous tissues.6

Of note, microfilaria were not observed by all participants due to slide variation.

References:

1. Duarte ER, Hamdan JS. Otitis in Cattle, an Aetiological Review. Journal of Veterinary Medicine, Series B. 2005;51: 1-7.

2. Gardiner CH, Poynton SL. An atlas of metazoan parasites in animal tissues. C.L. Davis Foundation; 2006.

3. Johnson SJ. Stephanofilariasis- a review. Helminthological Abstracts, Series A (Animal and Human Helminthology). 1987;56: 287-299.

4. Klei TR. Helminths of the skin. In: Kahn CM, ed. Merck Veterinary Manual. 10 ed. Kendallville, Indiana: Courier Kendallville, Inc.; 2010:826-840.

5. Mauldin EA, Peters-Kennedy J. Integumentary System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6 ed. China: Elsevier; 2016:686-687.

6. Mutinda M, Otiende M, Gakuya F, et al. Putative filariosis outbreak in white and black rhinoceros at Meru National Park in Kenya. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:206.

7. Tremlett, JG. Observations on the pathology of lesions associated with Stephanofilaria dinniki round, 1964 from the black rhinoceros (Diceros bicronis). J Helminthol. 1964; 38:171-174.