Wednesday Slide Conference, Conference 3, Case 3

Signalment:

17-year-old, intact female, rhesus macaque, Macaca mulatta, Non-human primate (NHP)

History:

This NHP was part of several animals who lived in a research colony in Texas for several years prior to being transported to Maryland. The animal had recently become very unthrifty with a very poor body condition. Due to a worsening condition, humane euthanasia was elected.

Gross Pathology:

The heart was diffusely enlarged up to 1.5 times the normal size and bilaterally the ventricular free walls were thin and flabby. The pericardium contained approximately 75 mL of serosanguineous fluid. In the left ventricle, there were multiple white nodules adhered to the endocardium. The serosal surfaces of the small and large intestines were reddened. The liver had a diffuse cobblestone appearance. The gallbladder was markedly enlarged up to three times normal. The splenic capsule had a diffusely nodular appearance. The right adrenal gland had a single, tan, 2 mm nodular lesion in the cortex. There was approximately 50 mL of serosanguineous fluid in the thorax and 50 mL of similar fluid in the abdomen.

Laboratory Results:

Biochemistry profiles showed chronically elevated liver and kidney values with low protein. Exact values were unavailable. PCR testing on formalin-fixed cardiac tissue was positive for Trypanosoma cruzi.

Microscopic Description:

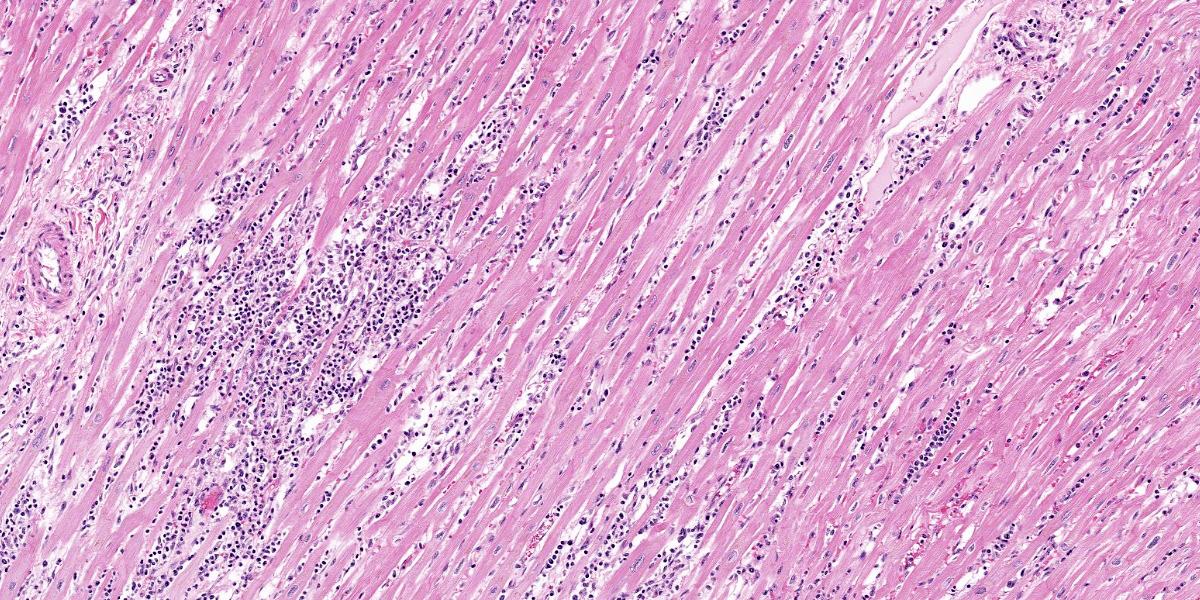

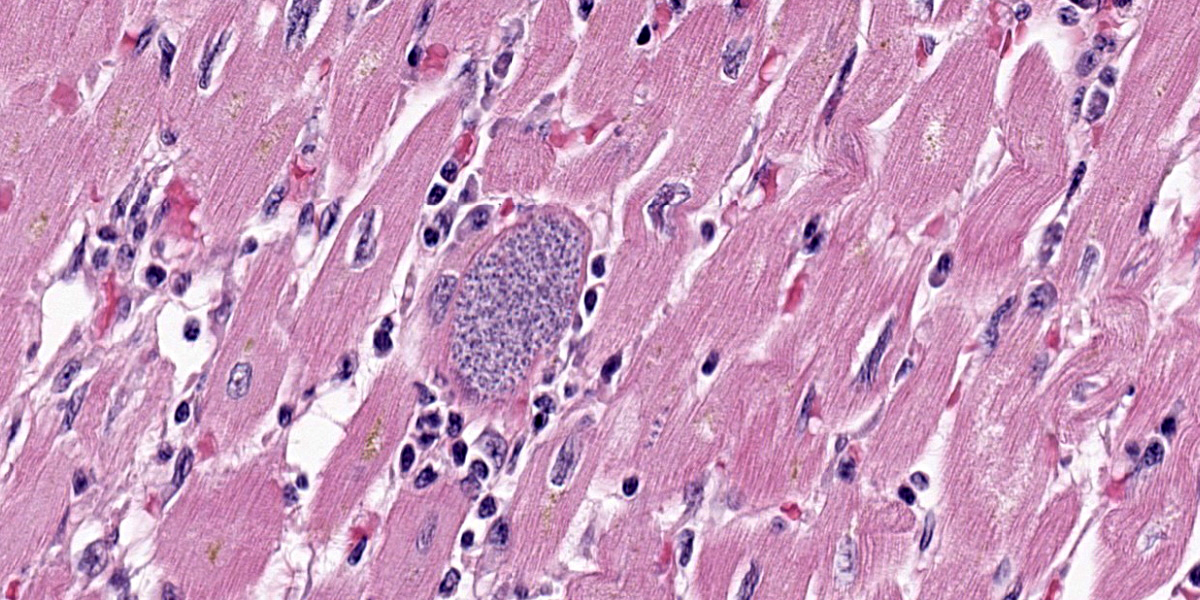

Diffusely and transmurally affecting approximately 60% of the section, large numbers of inflammatory cells composed of macrophages, lymphocytes, plasma cells, and neutrophils with fibroblasts surround, infiltrate, and replace cardiomyocytes. Cardiomyocytes adjacent to these inflammatory cells are often degenerate characterized by swollen, pale and vacuolated sarcoplasm or are necrotic characterized by hypereosinophilic sarcoplasm with loss of cross striations, and fragmentation of the nucleus with cellular and karyorrhectic debris. Multifocally within cardiomyocytes are numerous pseudocysts measuring up to 40 um x 90 um which contain a plethora of 2-4 um protozoal amastigotes with a basophilic nucleus and kinetoplast. Fibrin, hemorrhage, and edema is also present in these inflammatory regions. Present within the left ventricular lumen are multiple enmeshed clots adhered to the papillary muscles composed of fibrin, hemorrhage, edema, and similar inflammatory cells.

Contributor?s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Heart: Panmyocarditis, histiocytic and lymphoplasmacytic, chronic, diffuse, severe, with myocardial degeneration, necrosis, and loss, and intramyocytic protozoal amastigotes, rhesus macaque, non-human primate.

Contributor?s Comment:

The histopathologic findings and PCR test results are diagnostic for cardiac trypanosomiasis caused by Trypanosoma cruzi. T. cruzi is the causative agent for Chagas disease, otherwise known as American trypanosomiasis. Trypanosomes are hemoflagellate protozoans known to infect humans and a variety of domestic and wild animals throughout North and South America. In the southern United States, opossums, raccoons, and armadillos serve as the primary reservoir hosts.1,3,5,7

T. cruzi is most commonly spread through stercorarian transmission when its vector, the triatomine bug (also called the reduviid or kissing bug), defecates or urinates trypomastigotes of T. cruzi at the site of a recent blood feeding. Trypomastigotes from the feces or urine enter the wound and disseminate hematogenously to cardiomyocytes. Trypomastigotes invade cardiomyocytes where they develop within the sarcoplasm into amastigotes within a pseudocyst. After replication, the amastigotes mature into trypomastigotes, rupture the host cell, and re-enter systemic circulation. This infective form is then ingested by a triatomine bug during a blood feeding where it transforms into an epimastigote in the insect?s gut and replicates through binary fission while awaiting the cycle to begin anew.1,3,5,7,8 While the heart is the primary organ affected, amastigotes have also been identified in several other organs.3 In this case, a pseudocyst was also identified in the diaphragm. Additional documented forms of transmission include oral ingestion of the vector or contaminated feces, transplacental and transmammary transmission, blood transfusions, and organ transplantation.1,5,8

Classic clinical and pathologic findings follow a pattern of cardiac disease. In the acute phase, cardiac arrhythmias, sudden collapse, or even death, weak pulses, and signs of respiratory distress can all be expected. Animals that survive the acute phase can anticipate developing chronic heart disease. Cardiac dilatation is common as are more frequent cardiac arrhythmias and clinical signs consistent with unilateral or bilateral heart failure.3

Cytology of blood smears during the acute phase can be used to identify trypomastigotes present in the systemic circulation. In the chronic phase when parasitemia is lower, a thick-film buffy coat smear should be used to increase the concentration of the organisms. Lymph node aspirates and cytologic analysis of abdominal effusion has also been documented to identify T. cruzi. Serologic and molecular testing has also been useful in pre-mortem diagnosis.5

Post-mortem findings will vary depending on if the animal died during the acute or chronic phase of infection. Lesions from death during the acute phase include a pale myocardium with hemorrhages in the subendocardial and subepicardial surfaces. Right-sided heart lesions are often more severe than the left side. Generalized lymphadenopathy has also been reported. Chronically infected animals often present with generalized cardiomegaly with thinning of the ventricular free walls and a serosanguineous fluid in the pericardial, pleural, and abdominal cavities. Microscopic findings include multifocal to diffuse histiocytic to lymphoplasmacytic myocarditis with varying stages of cardiomyocyte degeneration and necrosis with fibrosis. The presence of intracardiomyocytic amastigotes is a very helpful but can be difficult to find especially in chronic cases.1,5

A recent study documenting the histologic findings of T. cruzi in domestic cats documented lymphoplasmacytic myocarditis with fibrosis in 42.1% of seropositive cats compared to 28.6% of seronegative cats. In the same study, PCR for T. cruzi was performed on a variety of tissues from seropositive and seronegative cats. PCR-positive tissues included heart, biceps femoris muscle, sciatic nerve, esophagus, and mesentery.8 Although CNS disease is considered an uncommon manifestation of T. cruzi infection in non-human mammals, disseminated trypanosomiasis with central nervous system (CNS) involvement was recently reported in four dogs, with CNS involvement confirmed by quantitative PCR. Lymphohistiocytic myocarditis and histiocytic meningoencephalitis with rare to numerous intralesional and intracellular amastigotes were reported in all 4 dogs, while gross lesions within the CNS were observed in 2/4 dogs.3

Contributing Institution:

Walter Reed Army Institute of Research; Department of Pathology; https://www.wrair.army.mil/

JPC Diagnosis:

Heart: Pancarditis, lymphoplasmacytic and histiocytic, chronic, multifocal to coalescing, marked, with fibrosis and numerous intrmyocytic amastogotes.

JPC Comment:

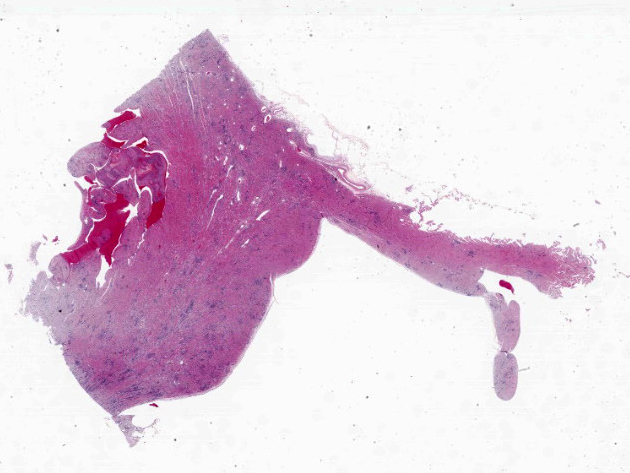

At first glance, this section of heart is nondescript save for the random, coalescing regions of basophilia (Figure 3-1) that represent the inflammatory cells in the myocardium that the contributor describes. On higher magnification however, there are a plethora of changes occurring in this case that provide some zest to the pathology palate. To wit, we ran special stains (Giemsa, PTAH, Masson?s trichrome) for this case and they did not disappoint. The degree of fibrosis in this case is not surprising given the loss of cardiac myocytes secondary to both rupture of amastigote-laden cells and the marked inflammatory response (figures 3-2 and 3-3), though cardiac fibrosis can also be a background lesion in aged macaques. In this case, trypanosomal amastigotes were obvious on H&E, though they were also highlighted metachromatically by Giemsa with the kinetoplasts being a sharp red against the medium blue background. We also ran a modified Gram stain (Brown-Brenn, Brown-Hopps) and fungal stains (GMS, PAS Light Green) which did not identify any concurrent infections in this animal. Although tinctorially similar to the myofibers, there are also two fibrin thrombi nestled within the ventricle as the contributor points out. Conference participants overall liked the quality of this slide and the descriptive features as they felt they were rewarding to discuss.

Natural infection of non-human primates with Chagas disease has been described in the veterinary literature previously. 2,4,6 Given the preponderance of primate facilities in Texas similar to where the animal in this case originated, discussion of trypanosomiasis and its impacts on medical research remains relevant. A similar case of trypanosomal myocarditis in a rhesus macaque was previously covered in Conference 17, Case 2, 2013-2014.

Finally, another important rule out for this case is leishmaniasis which appears nearly identically to trypanosomes histologically. In theory, the orientation of the kinetoplast (parallel to the nucleus for trypanosomes, perpendicular for Leishmania) might help to discriminate these entities, though PCR is preferable if available. The advancing range of reduviid bugs has implications on animal and human health that are not lost on us at the JPC. Given that the Department of Defense?s Military Working Dog Program is anchored in San Antonio, Texas6, we see several cases of canine trypanosomiasis each year when such cases were rarer previously. Given worldwide deployment of Military Working Dogs, discerning T. cruzi infection against other agents remains an important task.

References:

- Boes KM, Durham AC. Bone marrow, blood cells, and the lymphoid/lymphatic system. In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 7th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2022:834.

- Hodo CL, Wilkerson GK, Birkner EC, Gray SB, Hamer SA. Trypanosoma cruzi Transmission Among Captive Nonhuman Primates, Wildlife, and Vectors. Ecohealth. 2018 Jun;15(2):426-436.

- Landsgaard K, et al. Protozoal meningoencephalitis and myelitis in 4 dogs associated with Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Vet Pathol. 2023;60(2):199-202.

- Rovirosa--Hernández MJ, López-Monteon A, García-Orduña F, et al. Natural infection with Trypanosoma cruzi in three species of non-human primates in southeastern Mexico: A contribution to reservoir knowledge. Acta Tropica. 2021;213:105754.

- Snowden KF, Kjos SA. American trypanosomiasis. In: Greene CE, ed. Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier-Saunders; 2012:722-30.

- Tarleton R, Saunders A, Lococo B, et al. The Unfortunate Abundance of Trypanosoma cruzi in Naturally Infected Dogs and Monkeys Provides Unique Opportunities to Advance Solutions for Chagas Disease. Zoonoses. 2024;4(10).

- Valli VEO, Kiupel M, Bienzle D. Hematopoietic system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer?s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 3. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2016:121-124.

- Zecca IB, et al. Prevalence of Trypanosoma cruzi infection and associated histologic findings in domestic cats (Felis catus). Vet Parasitol. 2020;278:109014.