Signalment:

The referring veterinarian suspected tularemia due to positive cases in sheep in the same area the previous year.

Gross Description:

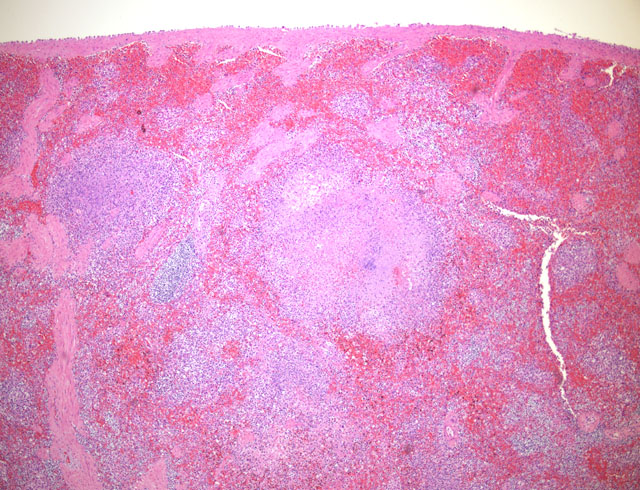

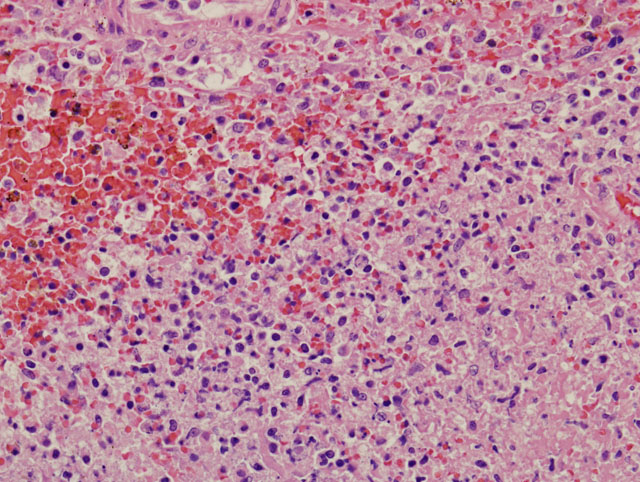

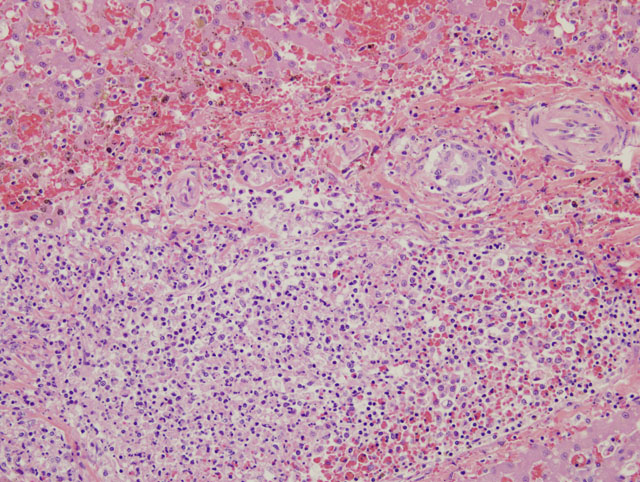

Histopathologic Description:

Other lesions include large necrotic foci in the mesenteric lymph node similar to those seen in the liver and spleen and smaller foci in the lung and bone marrow.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

The organism is a small Gram negative rod that is a facultative intracellular bacterium. It not only lives but proliferates in macrophages.(2) Transmission is by ingestion, inhalation, direct contact with skin or mucous membranes, or by arthropods, especially ticks and deer flies. Cats and dogs are thought to be somewhat resistant; however, this cat may well have been infected by ingestion of an infected rodent. Humans may be infected by direct contact or aerosols. Sheep are infected primarily by tick infestation.(4)

Clinical signs vary depending upon route of transmission. In humans the most common route of transmission is by direct contact in susceptible segments of the population (hunters, butchers, farmers, etc).(3) In these patients, the most common form of the disease is ulcerglandular, characterized by systemic illness with a skin ulcer at the site of infection and swelling and drainage of local lymph nodes. The increasing concern over weaponized bacteria for biological attack has brought renewed interest in the study of forms of tularemia caused by inhalation. The typhoidal form of tularemia is characterized by fever, prostration, and absence of lymphadenopathy. The pneumonia resulting from typhoidal tularemia can be severe and fatalities may reach 35%. The disease in domestic animals may be subclinical or may manifest as fatal septicemia.(4) Clinical signs previously reported in cats with tularemia include vomiting, weight loss and anorexia.(3)

The characteristic gross lesion of miliary foci of hepatic necrosis in rodents is not always visible in other species. Multifocal splenic necrosis, as seen grossly in this case, has been previously reported in other feline cases.(3) Histologic lesions of multifocal necrosuppurative inflammation in the liver, lung, spleen, and lymph nodes is characteristic of Francisella tularensis, but overlaps with other septicemic organisms such as Yersinia pestis and Yersinia psuedotuberculosis.(4) If possible, animals dying with a high suspicion of tularemia (signs of septicemia in an animal from an endemic area) should be necropsied under BL-2 conditions and culture should only be attempted in BL-3 facilities due to risks to laboratory personnel. In this case, characteristic gross and histologic lesions along with positive PCR for F. tularensis allowed fresh tissues to be forwarded to an appropriate laboratory for confirmation of the diagnosis.Â

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Rodents and lagomorphs are often found dead, but if found alive, they display signs of weakness and fever with lymphadenopathy. Tularemia causes a multifocal necrotizing hepatitis in rodents. Possible differential diagnoses for this lesion in rodents include Tyzzers disease, (Clostridium piliforme), salmonellosis, Listeria monocytogenes, Toxoplasma gondii, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, and Yersinia enterocolitica.(1,4)

References:

2. Sjdstedt A: Tularemia: epidemiology, physiology and clinical manifestations. Ann NY Acad Sci 1105: 1-29, 2007

3. Tularemia. Institute for International Cooperation in Animal Biologics, The Center for Food Security and Public Health, Iowa State University, Ames, IA. www.cfsph.iastate.edu

4. Yalli VEO: Hematopoietic system. In: Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., pp. 297-298. Elsevier Limited, Edinburgh, UK, 2007