Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 12

December 13th, 2017

CASE I: 16L-2815 (JPC 4102118).

Signalment: 8 year-old, mare, Irish sport horse, Equus caballus, equine.

History: The animal presented with clinical signs consistent with cauda equina syndrome from 29th November 2015. Clinical neurological manifestations were an inability to pass feces and a progressive reduction in tail, anal and vaginal tone. Posteriorly there was a bilateral muscle atrophy of the muscles of the proximal hind limbs and the muscle of the tail head. Unilateral paresis of the right hind limb appeared and developed into a paraparesis. Steroids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in combination with neuromodulator treatment were administered.

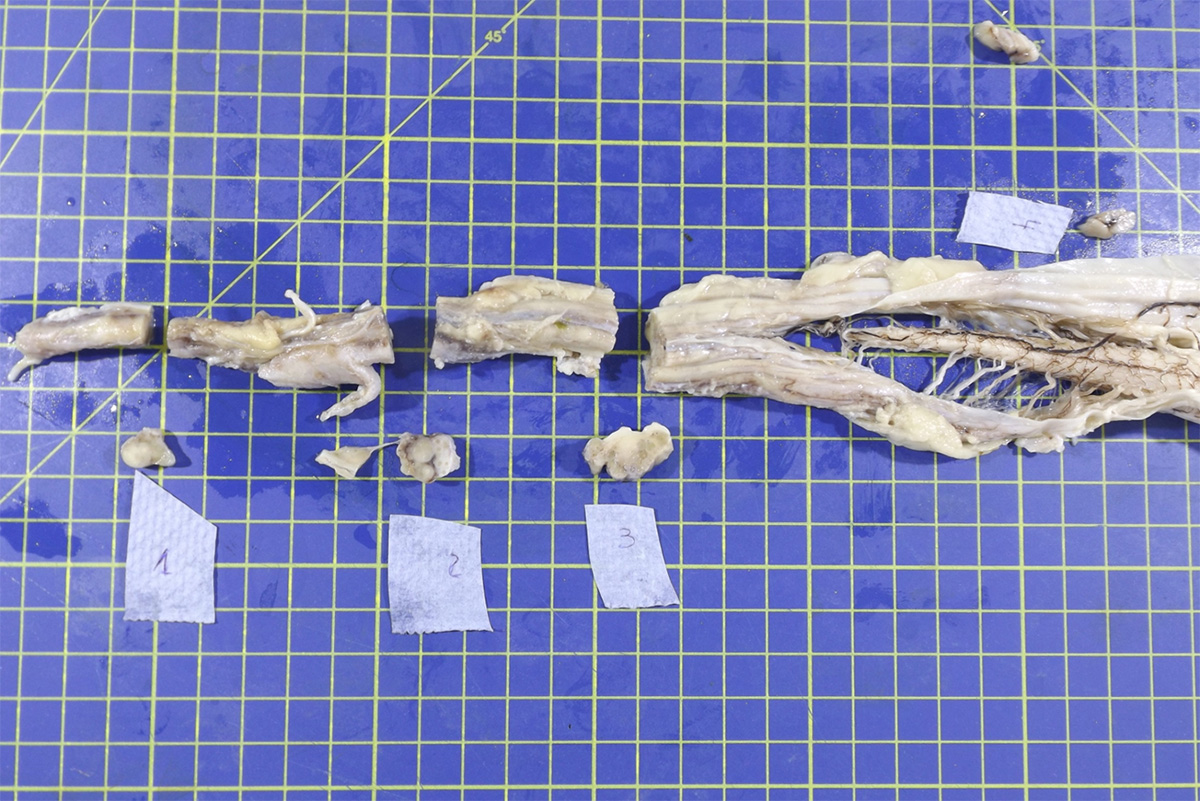

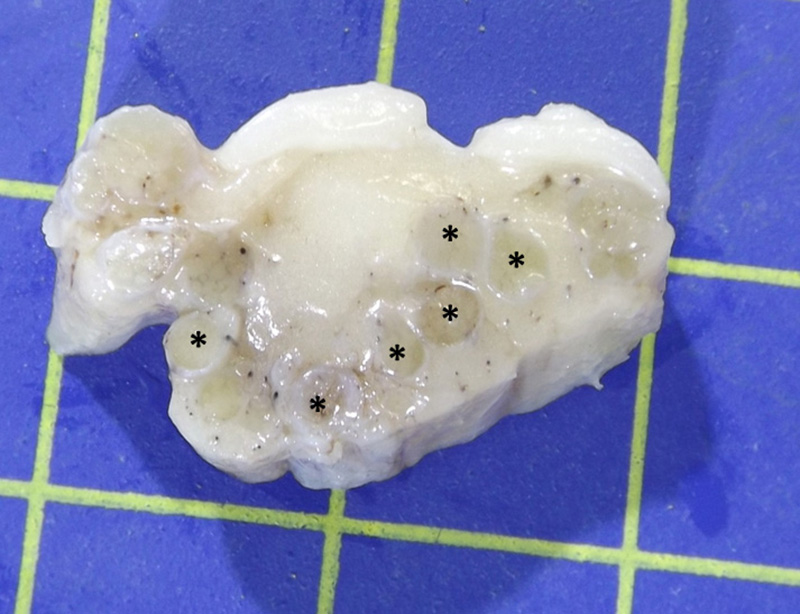

Gross Pathology: The lumbosacral spinal cord and extradural nerve roots (cauda equina) were markedly enlarged by an abundant grey to whitish irregular material with variable consistency and occasionally a nodular pattern. This material was consistently attached to the epineurium of the sacral nerve roots and was present from the Conus medulari, and between the nerve prolongations of the fillum terminale and cauda equina.

Laboratory results:

None provided.

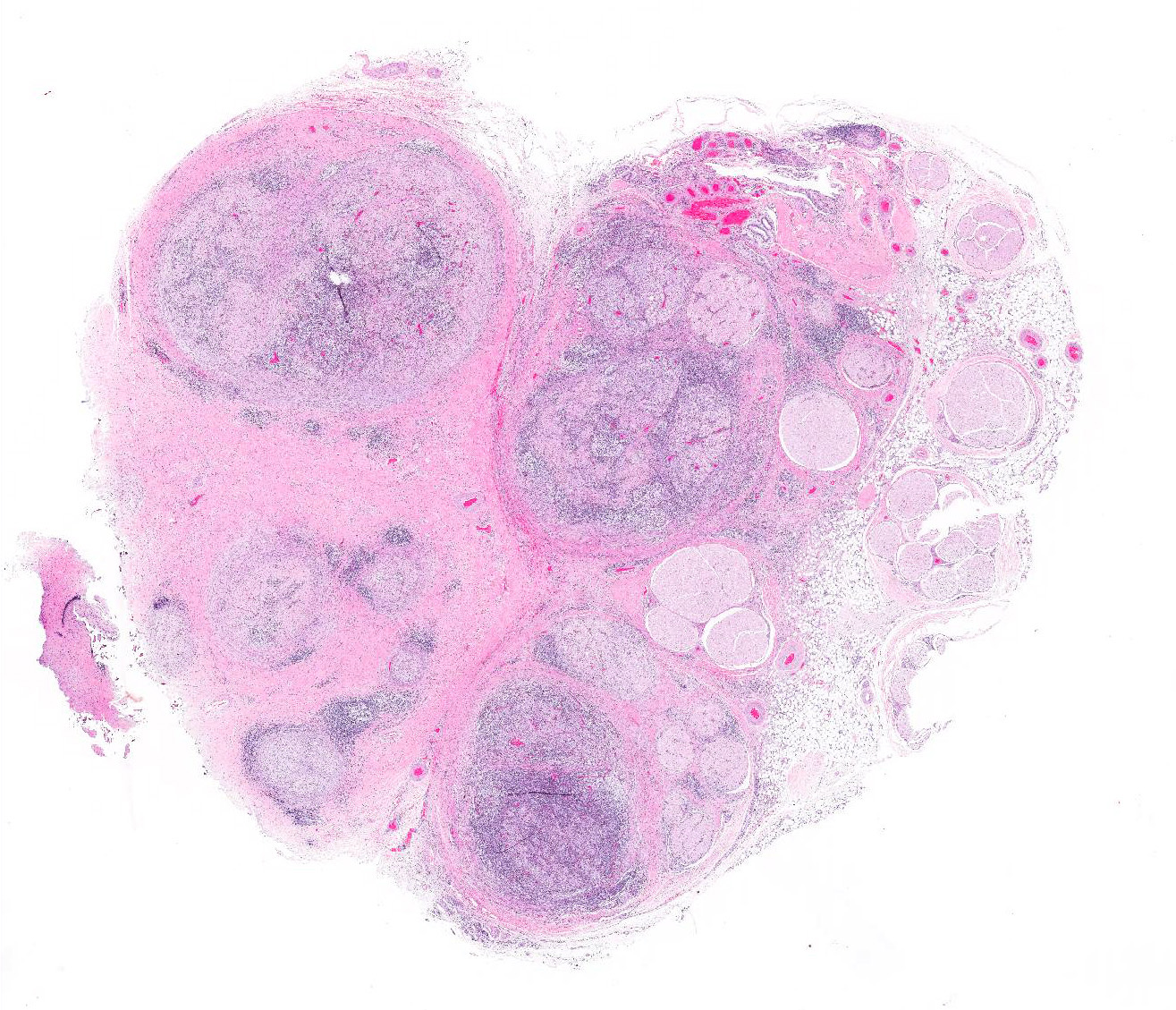

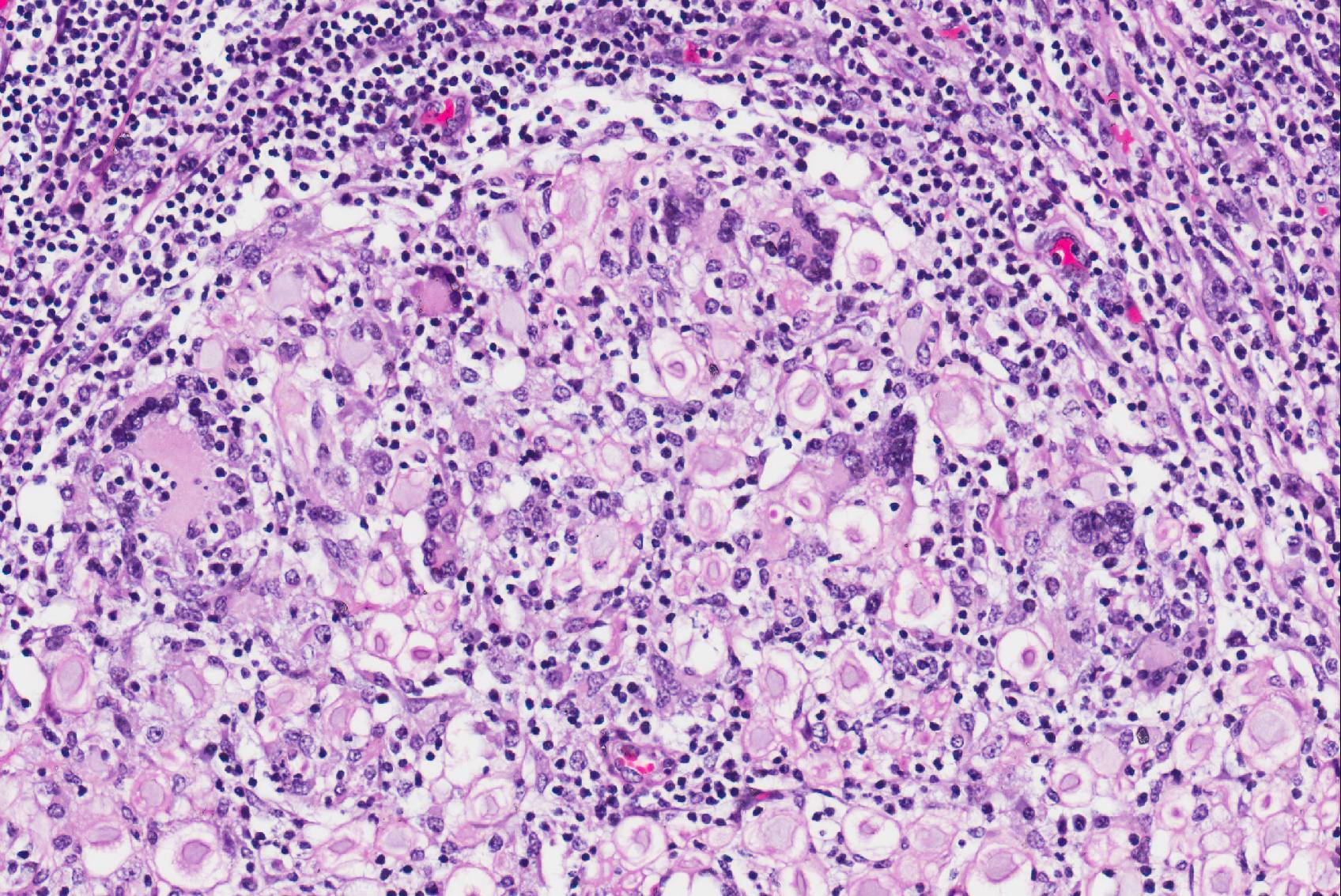

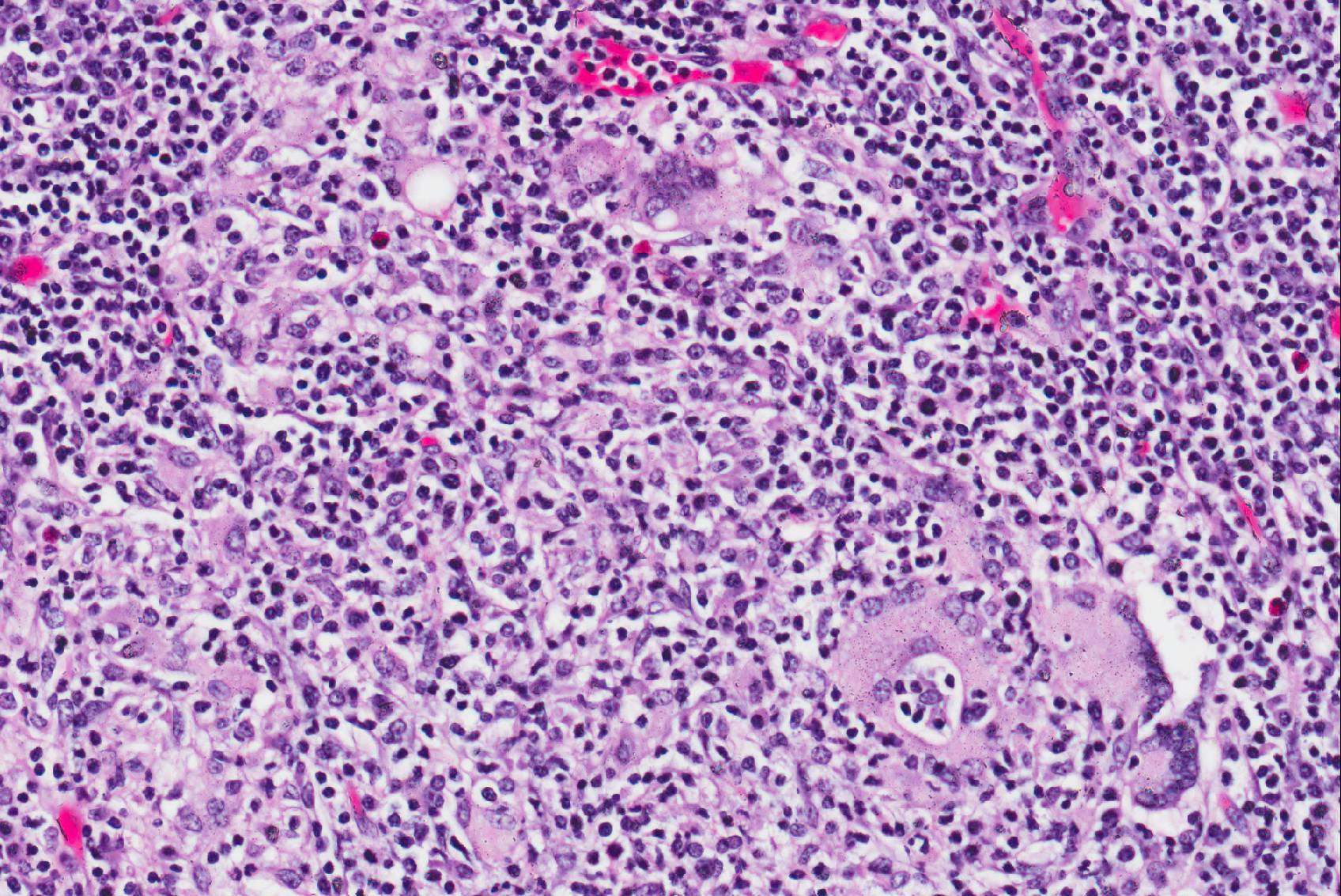

Microscopic Description: Cauda equina: There are multiple cross sections of nerve roots, epidural adipose tissue and connective tissue. The majority of the fibrous tissue corresponds to the epineurium which is markedly expanded by an increased volume of dense irregular connective tissue (severe fibrosis). The fibrotic epineurium is infiltrated by a moderate to severe, multifocal inflammatory infiltrate composed of epithelioid macrophages, often surrounded by large numbers of lymphocytes, fewer plasma cells and occasional Langhans type multinucleated giant cells; there is multifocally mild hemorrhage. The majority of nerve roots are affected by a similar inflammatory process, the severity of these changes ranging from minimal to severe. The most severely affected nerve roots are entirely effaced by multifocal areas of necrosis characterized by large amounts of eosinophilic and basophilic amorphous material (myelin debris) and infiltrated by large numbers of inflammatory cells (macrophages, lymphocytes), and intact axons and myelin sheaths are rarely observed. In those nerves less severely affected, the epineurium and perineurium are markedly enlarged due to high number of infiltrating macrophages and lymphocytes. There is a reduction of nerve fibers numbers, and nerves variably exhibit swollen axons (spheroid), moderately distended myelin sheets and occasionally phagocytic cells within areas of myelin degradation (digestion chambers). Other peripheral nerves are minimally affected or are unremarkable.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Horse, lumbosacral spinal nerve roots (cauda equina, fillum terminale): Multifocal, severe, chronic, granulomatous polyradiculoneuritis with multifocal nerve necrosis, Wallerian axonal degeneration and epineurial fibrosis.

Contributor’s Comment: Polyneuritis equi (cauda equina neuritis) is an uncommon sporadic disease of the horse of an unknown etiology but is considered likely to be an autoimmune or immune-mediated disorder; it is considered by some authors to be reactive condition from previous inflammatory or infectious episodes2. Clinically, animals exhibit a slowly progressive peripheral neurological disorder, localizing to the sacrococcygeal nerves (cauda equina syndrome) and is most commonly observed in females9. Formerly known as cauda equina neuritis in horse, the name of the disease was updated to polyneuritis equi (PNE) based on descriptions in which the involvement of spinal nerves at various levels of the spine and cranial nerves were also reported11.

Clinical examination allows the neurolocalization of lesions to the level of spinal nerve roots, frequently of the sacral spinal segments4. It represents an exclusion diagnosis with and is considered to be of idiopathic origin1. A case of verminous migration by Halicephalobus gingivalis has been described in association with the typical inflammatory reaction of cauda equina neuritis, however5. Equine neurotropic viruses such as equine herpesvirus 1 (EHV1) and West Nile virus have been ruled out as causes in cases reported in recent literature1. Some older studies have demonstrated an association between the lesion of PNE and infectious agents such EHV1, equine adenovirus type 1, equine arteritis virus, and Streptococcus equi ssp. equi with the suggestion that the lesion may have evolved through a bystander mechanism in which the presence of the inflammatory infiltrate damages the nerves, rather than the direct actions of these organisms as causal agents9. Additionally, exclusion of traumatic, developmental, neoplastic or toxic diseases should be ruled out before confirming the diagnosis11.

The typical gross and microscopic lesions that characterize this disease are very much in keeping with the case we present. Typical gross lesions include thickening of the nerve roots of the sacral and coccygeal nerves which may be discolored by acute and / or chronic hemorrhage. Histologically a severe granulomatous neuritis with marked fibrosis and degenerative / necrotizing changes to nerve fibers is described2.

Cauda equina syndrome also is described in dogs with a higher incidence in large breeds9. Nonetheless in this species it is defined as a compression of the spinal cord due to stenosis of the lumbosacral central canal. Dogs and cats also develop acute polyradiculoneuritis with presumed autoimmune origin and low frequent affectation of the cauda equina9.

In humans and laboratory animals, Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS) and allergic neuritis (EAN) constitute infectious autoimmune diseases that have been compared with PNE in horses and acute polyneuritis in dogs. Descriptive studies including the characterization of the histopathological lesions in horses3,10 are indicative of immune reactions against myelin in PNE. A 2008 study into the composition of the inflammatory infiltrates of PNE9 demonstrated that both T and B lymphocytes were present within the lesions, along with macrophages. The authors consider the question as to whether there is a T-cell mediated immune response against myelin, or if the B-cells are producing an antibody against the P2 protein of myelin, or there may be a combination of both mechanisms. A 2015 study3 of equine protozoal myeloencephalitis, caused by Sarcocytis neurona, demonstrated that some horses with antibodies against this organism also produce antibodies against myelin protein peptide. This suggests one possible aetiological relationship between an infectious organism and an immune-mediated peripheral neuritis.

JPC Diagnosis: Spinal cord, cauda equina: Polyradiculoneuritis, granulomatous, chronic, diffuse, severe with marked epineurial fibrosis and widespread axonal degeneration, Irish sport horse (Equus caballus), equine.

Conference Comment: The cauda equina is composed of roots of the sacral and coccygeal spinal nerves and is present in all mammalian species except for birds, whose spinal cord extends throughout the entire spinal canal. These nerves exit the caudal end of the spinal cord and travel through the remainder of the spinal canal longitudinally to reach their intended intervertebral foramina. The cauda equina develops after birth as the vertebral column continues to grow, resulting in cranial displacement of spinal cord segments relative to their corresponding vertebrae (whereas during gestation the spinal cord segments are aligned with their corresponding vertebrae)7.

First described in 1897 by Dexler as a combination of tail and anal sphincter paralysis due to chronic inflammation and fibrosis of the extradural portions of the nerve roots of the cauda equina, neuritis of the cauda equina has been identified throughout the years in numerous adult horses and ponies of various breeds. Many of the clinical signs (most of which are listed above) including urinary and fecal incontinence, perineal anesthesia, tail paralysis, muscle atrophy and weakness, and hind limb ataxia can be attributed to affected sacrocaudal nerve roots. However, animals often have additional clinical signs attributable to cranial nerve roots being affected such as facial paralysis, head tilt, and wasting of the masticatory muscles. The variety of affected nerves led to this syndrome being more aptly named “polyneuritis equi”8. In this case, attendees noted the variation of maturity of fibrous connective tissue throughout the lesion - ranging from hypertrophied fibroblasts and loosely packed immature fibrous connective tissue to dense mature collagen, denoting the diseases development over time.

Contributing Institution:

Department of Veterinary Pathology, Infection and Public Health

Institute of Veterinary Science

University of Liverpool

Leahurst Campus

Chester High Road

Neston

CH64 7TE

- Aleman M, Katzman SA, Vaughan B, Hodges J, et al. Antemortem diagnosis of polyneuritis equi. J Vet Intern Med. 2009;23(3):665-8.

- Cantile C, Youssef S. Nervous system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 1. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:374-375.

- Ellison S, Kennedy T, Schweiss L. Serum antibodies against a reactive site of equine myelin protein 2 linked to polyneuritis equi found in horses diagnosed with EPM. Intern J Appl Res Vet Med. 2015;13(3):164-170.

- Hahn CN. Miscellaneous disorders of the equine nervous system: Horner’s syndrome and polyneuritis equi. Clin Tech Equine Pract. 2006;5:43–48.

- Johnson JS, Hibler CP, Tillotson KM, Mason GL. Radiculomeningomyelitis due to Halicephalobus gingivalis in a horse. Vet Pathol. 2001;38:559-561.

- Meij BP, Bergknut N. Degenerative lumbosacral stenosis in dogs. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2010; 40:983–1009.

- Stoffel MH, Oevermann A, Vandevelde M. Functional neuroanatomy. In: Bolon B, Butt MT, eds. Fundamental Neuropathology for Pathologists and Toxicologists: Principles and Techniques. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2011:18-19.

- Summers BA, Cummings JF, de Lahunta A. Diseases of the peripheral nervous system. In: Duncan L, McCandless PJ, eds. Veterinary Neuropathology. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1995:432-434, 454-455.

- Vandevelde M, Higgins RJ, Oevermann A. Inflammatory diseases. Veterinary Neuropathology: Essentials of Theory and Practice. New York: Willey – Blackwell; 2012.

- Van Galen G, Cassart D, Sandersen C, Delguste C, et al. The composition of the inflammatory infiltrate in three cases of polyneuritis equi. Equine vet. J. 2008;40(2):185-188.

- Vatistas N, Mayhew IG. Differential diagnosis of polyneuritis equi. In Practice. 1995;17:26–29.