Signalment:

Gross Description:

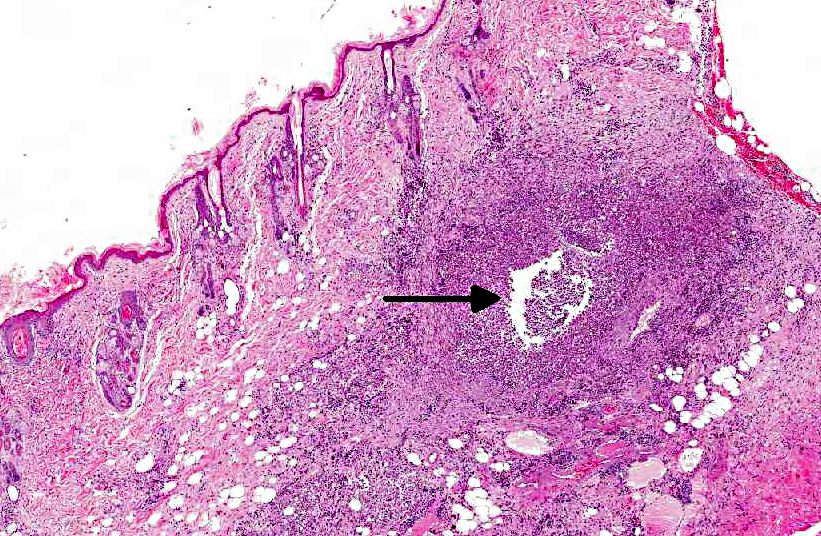

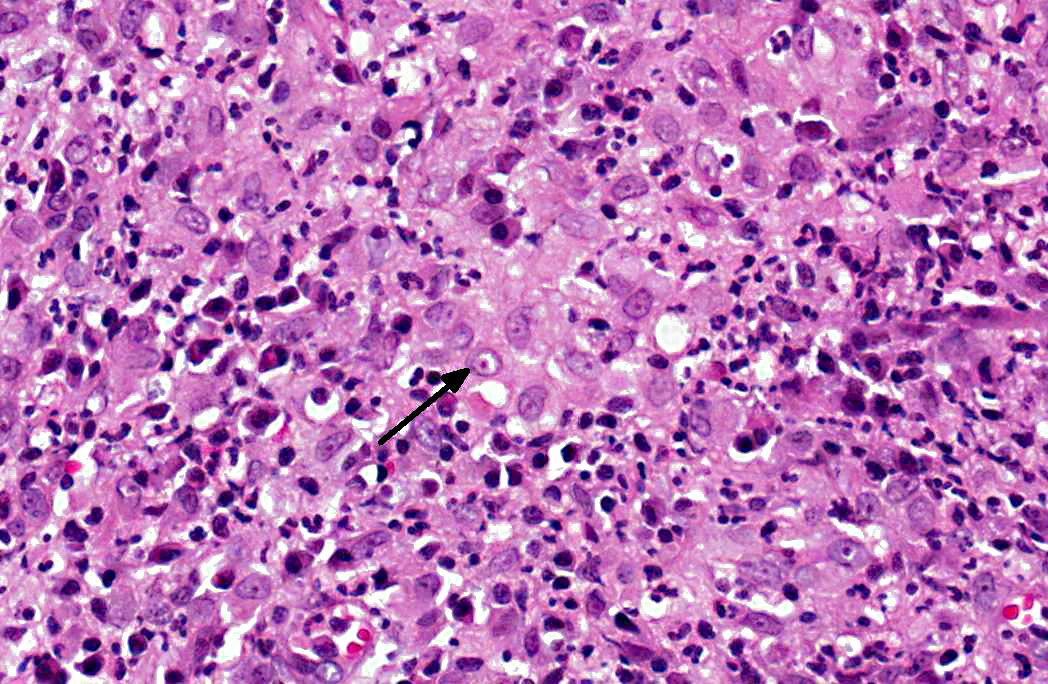

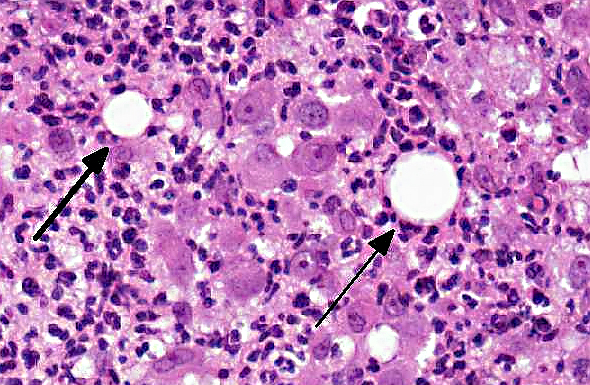

Histopathologic Description:

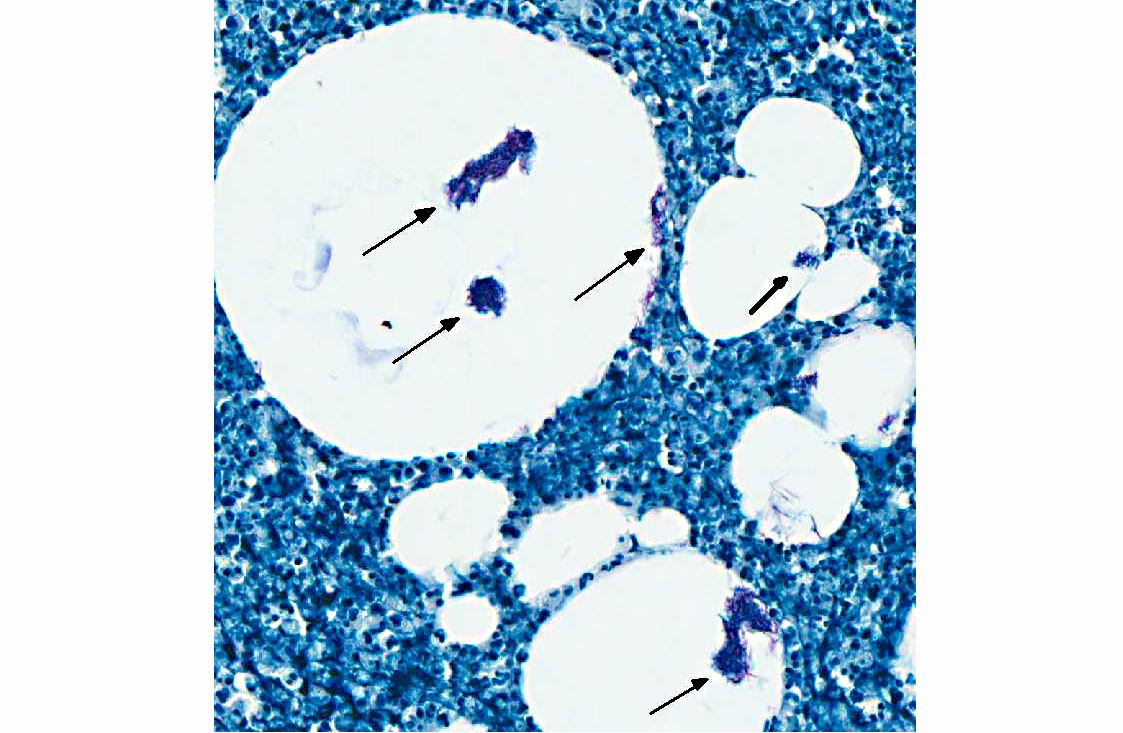

Acid fast stain (Ziehl-Neelsen): Many intravacuolar and intrahistiocytic acid-fast, 3-5 μm, filamentous bacilli are present.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

The feline leprosy group is comprised of obligate pathogens and can be subdivided into lepromatous (multibacillary) and tuberculoid (paucibacillary) forms.(3,6) Affected cats are typically young adults (1-3 years old) and lesions typically occur on the head, limbs, and trunk.(3,4,6) Regional lymphadenopathy may be present, but affected cats are otherwise healthy.(3,4) The mode of transmission is thought to be by rodent or cat bites, biting insect vectors, or soil contamination of cutaneous wounds.(6) The causative agent is presumed to be Mycobacterium lepraemurium; however, other potentially causative mycobacteria (M. visibilis, M. malmoense) have been isolated from cutaneous lesions clinically consistent with feline leprosy by molecular techniques.(4,6) M. lepraemurium does not grow in culture using standard techniques, but has been isolated by PCR with DNA sequencing.(6) Feline leprosy has no known zoonotic potential. Nerve involvement is not a characteristic feature of feline leprosy and is sporadic.(4)

The causative agents of cutaneous tuberculosis, M. bovis and M. tuberculosis, are also considered obligate pathogens. Cutaneous infections are rare. Feline cutaneous mycobacteriosis is most often caused by M. bovis.(3) Gastrointestinal and pulmonary infections are more common. Infections of the gastrointestinal tract and mesenteric lymph nodes usually occur following ingestion of milk or meat of infected cattle.(3) Cutaneous infections can occur alone (rare) or in combination with disseminated infection.(4,6) Lesions of feline cutaneous mycobacteriosis typically occur on the face, neck, shoulders, and forepaws. Less commonly the lesions occur on the ventral thorax and tail. Skin lesions can develop from bite wounds or as a result of dissemination from the gastrointestinal tract. Affected cats typically present with a local or generalized lymphadenopathy.(3) The causative agents of cutaneous tuberculosis are zoonotic.

Atypical mycobacteriosis (rapid growing Runyon Group IV mycobacteria) are considered opportunistic pathogens saprophytes or facultative pathogens that are ubiquitous in soil, water, and decomposing vegetation.(3,4,6,8,10) Included in the atypical group are M. fortuitum, M. phlei, M. smegmatis, M. chelonae, M. abscessus, M. flavescens, M. thermoresistible, and M. xenopi. The Runyon Group IV mycobacteria have a predilection for lipid rich tissues. Consequently, lesions characteristically occur on the ventral abdomen in the subcutaneous fat of inguinal area in cats.(4,5,6) Female cats are overly represented possibly due to the propensity of spayed females to become obese.(3,7) Studies have shown that introduction of acid-fast bacilli into adipose tissue facilitates their pathogenicity, possibly by providing nutrients for growth or by protecting them from the host immune response.(1,4,8,10) Infections occur via wound contamination or traumatic implantation. Consequently, many cats with atypical mycobacteriosis have a history of previous trauma.(4,5) Animal-to-animal transmission is not thought to occur and affected cats are usually not immunocompromised.(4,8) Atypical mycobacteriosis is not considered zoonotic.Â

Cutaneous lesions with atypical mycobacteria have been reported primarily in cats.(4,6) The clinical course is prolonged and lesions present as single or multiple cutaneous and subcutaneous nodules, diffuse swellings, plaques, or purpuric macules.(4) Fistulous tracts discharge serous, serosanguinous, or purulent exudates that are not usually malodorous.(4,8) Lesions slowly enlarge and eventually may encompass the entire ventrum and extend up the lateral trunk. Undermining of peripheral skin is characteristic with purple depressions (thin skin) overlying accumulations of pus.(5) Despite extensive cutaneous involvement, most animals remain active with no systemic signs of illness.(4,8)

Histologically, the epidermis is usually acanthotic or ulcerated with multinodular to diffuse pyogranulomatous dermatitis and panniculitis.(5) Thin rims of neutrophils with a wider zone of epithelioid macrophages usually surround varisized lipocysts (clear zones comprised of residual lipid from degenerating adipocytes).(5,6) Pyogranulomas without central spaces (lipocysts) may be seen as well. Pyogranulomas are often confluent and interspersed with diffuse inflammation composed primarily of macrophages and neutrophils. Chronic lesions may contain peripheral lymphoid nodules and/or fibrosis. Giant cells are usually absent.(5) Rapidly growing opportunistic mycobacteria may or may not be difficult to find in tissue section and have been described as rare to numerous.(4,8) When numerous, mycobacteria may be partially visible on hematoxylin and eosin (HE) stained tissue. Fites stain (a Fite-Faraco modification of the acid-fast stain) is useful in accentuating difficult-to-see mycobacteria. Mycobacteria are most commonly found in lipocysts due to protective fat, but may also be present in macrophages.(5)

In summary, pyogranulomas surrounding clear central spaces are very suggestive of a rapidly growing mycobacterial infection with HE stain, but may also be seen in other deep infections (e.g., higher bacteria). Demonstration of acid-fast organisms in lipocysts is highly supportive of the diagnosis; however, this should be confirmed by culture or molecular techniques.(5)

The differential diagnosis for cutaneous infection with rapid growing mycobacteria includes bite wound abscesses, deep mycotic or bacterial infections, sterile nodular panniculitis, and foreign body reactions.(5) Deep wedge biopsies are preferred over punch biopsies for diagnosis since inflammation is most intense in the subcutaneous fat.(4,5)

Cases of feline atypical mycobacteriosis carry a guarded prognosis as treatment can be challenging, especially with chronic lesions.(5,10) Treatment involves radical surgical debridement followed by long-term (3-6 months) treatment with concurrent administration of multiple antimicrobial agents.(5,8,10) Identification by culture or molecular techniques is required so that appropriate therapy and zoonotic potential can be determined.(3,4) Infective mycobacterium can be difficult to culture and repeated cultures may be necessary to yield a positive response.(8)

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Haired skin: Dermatitis, cellulitis and panniculitis, pyogranulomatous, necrotizing, focally extensive, severe, with lipocysts and many intravacuolar and intrahistiocytic 3-5 μm filamentous acid-fast bacilli.

2. Haired skin: Dermatitis, eosinophilic and mastocytic, subacute, multifocal, mild with bacterial folliculitis and rare intracorneal pustules.

Conference Comment:

In addition to the prominent pyogranulomatous dermatitis, panniculitis and cellulitis, conference participants noted a second, more subtle lesion consisting of eosinophilic and mastocytic dermatitis; the relationship between the two lesions is uncertain. Additionally, conference participants debated the microscopic presence of fistulous tracts, which would correlate well with the usual gross findings in atypical cutaneous mycobacteriosis.

References:

2. Cohen NR, Garg S, Brenner M. Antigen Presentation by CD1 Lipids, T Cells, and NKT Cells in Microbial Immunity [abstract]. Adv Immunol. 2009;102:1-94. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed. Accessed October 6, 2012. PMID: 19477319.

3. Davies JL, Sibley JA, Myers S, et al. Histological and genotypical characterization of feline cutaneous mycobacteriosis: a retrospective study of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues. Vet Dermatol. 2006;17:155-162.

4. Ginn PE, Mansell JEKL, Rakich PM. Skin and appendages. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol. 1, 5th ed. New York, NY: Elsevier Saunders; 2007:687-690.

5. Gross TL, Ihrke PJ, Walder EJ, et al. Skin Diseases of the Dog and Cat Clinical and Histopathological Diagnosis. 2nd ed. Ames, Iowa: Blackwell Science Ltd; 2005:283-287.Â

6. Hargis AM, Ginn PE. The integument. In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2007:1185-1187,

7. Indrigo J, Hunter RL, Actor JK. Cord factor trehalose 6,6-dimycolate (TDM) mediates trafficking events during mycobacterial infection in murine macrophages. Microbiology. 2003;149(8):2049-2059.

8. Malik R, Wigney DI, Dawson D, et al. Infection of the subcutis and skin of cats with rapidly growing mycobacteria: a review of microbiological and clinical findings. J Feline Med Surg. 2000; 2(1):35-48.9.Â

9. Montamat-Sicotte DJ, et al. A mycolic acid-specific CD1-restricted T cell population contributes to acute and memory immune responses in human tuberculosis infection. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(6):2493-503.Â

10. Wilson VB, Rech RR, Austel MG, et al. Pathology in Practice. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2011;238(2):171-173.