Signalment:

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

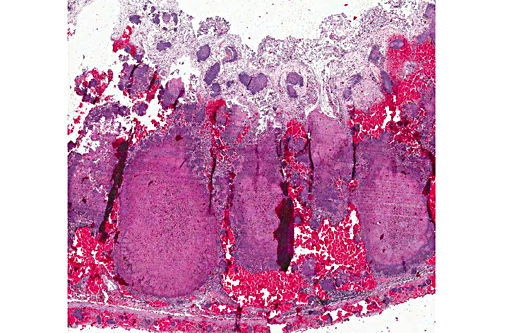

Caecum: The mucosa and the normal lymphatic tissue are mostly replaced by large hemorrhages and large focal areas of necrotic debris, mixed inflammatory cells and colonies of rod bacteria. The lesions extend to the submucosa, muscular layer and serosa.

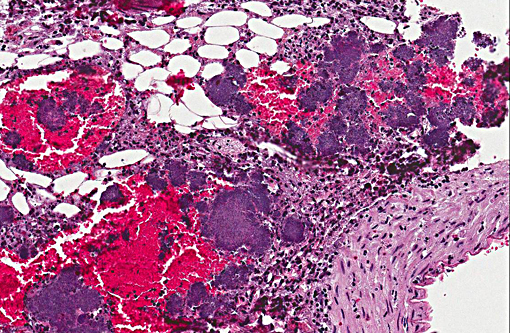

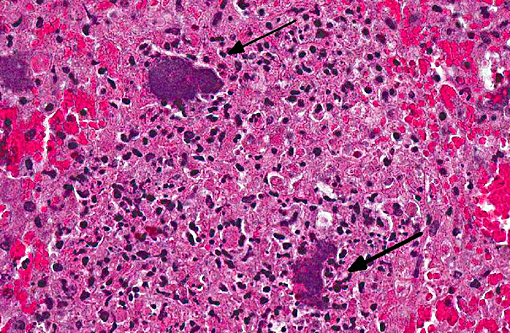

Liver: There are multiple, small, often coalescent necrotic foci with colonies of rod bacteria in the middle. Bacterial emboli are also present widely in hepatic sinuses.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

JPC Diagnosis:

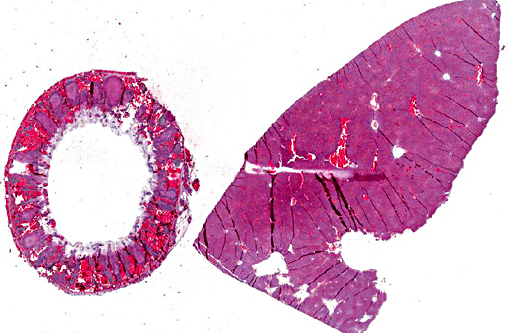

Appendix: Appendicitis, necrotizing, transmural and hemorrhagic, diffuse, severe with marked lymphoid necrosis, vasculitis and numerous large colonies of gram negative bacilli.

Liver: Hepatitis, necrotizing, multifocal to coalescing, severe with numerous large colonies of gram negative bacilli.

Conference Comment:

The bacteria also produce other proteins such as YadA and Ail that protect against phagocytosis and the host immune response. Yersinia largely resides extracellularly as small colonies in suppurative foci in the lamina propria of the intestine as well as in lymph nodes, but may also be found intracellularly.(9)

Aside from rabbits, other small mammals such as hamsters and guinea pigs can also become infected with Y. pseudotuberculosis. Additionally, virulent strains have been demonstrated experimentally to cause persistent infection in the cecum of asymptomatic mice, and are shed in the feces.(1) Gross lesions in the acute form of Y. pseudotuberculosis include pale, yellow-white nodules in the intestinal wall with mucosal ulceration in the distal small intestine and cecum. In subacute and chronic forms of the infection caseous and/or miliary lesions may be seen in the liver, spleen, mesenteric lymph nodes and lungs.(6) Y. pseudotuberculosis is often grouped with Y. enterocolitica as Yersiniosis as infections with these two organisms cannot be reliably distinguished without culture. The disease has also been described in large animal species including sheep, cattle, deer, goats, pigs as well as nonhuman primates. Similar to small mammals, the intestine, mesenteric lymph nodes and liver may be affected and microscopic lesions include abundant colonies of gram negative coccobacilli in the distal small intestine, especially at Peyers patches, as well as in the large intestine. As infection progresses, suppurative foci eventually replace Peyers patches and multifocal microabscesses may be seen in the lamina propria of the intestine. Microabscesses or pyogranulomatous foci may also be seen in mesenteric lymph nodes.

Other genera of bacteria to include on the differential diagnosis list for large colonies of bacteria seen microscopically include Actinomyces, Actinobacillus, Trueperella, Corynebacterium, Staphylococcus, and Streptococcus.

In conference, the section of appendix was described as being diffusely and transmurally effaced by focally extensive areas of lymphoid necrosis centered on lymphoid tissue. Hemorrhage, edema and multifocal venous fibrin thrombi were also described, and the presence of large colonies of short bacterial rods was a key feature in this case. The liver was described as being approximately 15-20% affected by random foci of lytic necrosis. Affected areas contain a mixed inflammatory cell population, predominantly degenerate and viable heterophils, as well as colonies of short bacterial rods and venous fibrin thrombi. The sections of liver and appendix are moderately autolytic, which is not uncommon in rabbits/hares due in part to post mortem production and retention of heat.

Many participants described the section of appendix as cecum or colon, not recognizing the unique appearance of the rabbit appendix. The terminal portion of the cecum is known as the vermiform appendix, a thick-walled blind-ended tube which contains abundant large, expansive, lymphoid follicles which span the depth of the appendix wall, and in this case are characterized by extensive lymphoid necrosis. A morphologically similar structure is present at the entrance to the cecum and is known as the sacculus rotundas.(5,8) These structures are important lymphoid organs in the rabbit and hare, which play a role in the development of B lymphocyte diversification.(3)

References:

1. Fahlgren A, Avican K, Westermark L, Nordfelth R, Fallman M. Colonization of cecum is important for development of persistent infection by Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2014; 82(8):3471-82.

2. Gasper PW, Watson RP. Plague and Yersiniosis. In: Williams ES, Barker IK, eds. Infectious diseases of wild mammals. 3rd ed. London, UK: Manson Publishing Ltd; 2001:313-329.

3. Hanson NB, Lanning DK. Microbial induction of B and T cell areas in the rabbit appendix. Dev Comp Immunol. 2008; 32(8):980-991.

4. Mair NS. Yersiniosis in wildlife and its public health implications. J Wildl Dis. 1973; 9:64-71.

5. Manning PJ, Ringler DH, Newcomer CE. The biology of the laboratory rabbit. 2nd ed. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1994:53.

6. Percy DH, Barthold SW. Pathology of laboratory rodents and rabbits. 3rd ed. Ames, IA: Blackwell publishing; 2007:192, 226, 283.

7. Rimhanen-Finne R, Niskanen T, Hallanvuo S, Makary P, et al. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis causing a large outbreak associated with carrots in Finland. Epidemiol Infect. 2006; 137(3):342-347.

8. Snipes RL. Anatomy of the Rabbit Cecum. Anat Embryol. 1978; 155:57-80.

9. Uzal FA, Plattner BL, Hostetter JM. Alimentary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Vol2. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2015:176-177.