Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2019-2020

Conference 11

20 November 2019

Charles W. Bradley, VMD,

DACVP

Assistant Professor, Pathobiology

University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine

4005 MJR-VHUP

3900 Delancey Street

Philapdelphia, PA, 19104

CASE II: WSC-SC-2 (JPC 4114031).

Signalment: 7 year old, male neutered Munchkin, Felis catus

History: Since birth, the patient has suffered from chronic dermatophytosis, which was diagnosed on histopathology when the cat was approximately 1 year old. The cat was treated with ketoconazole and lime sulfur dips. Since then, the cat intermittently developed raised, alopecic skin lesions that would t wax and wane without treatment. Four months prior to the current submission, the cat had lost 40% of his body weight and had intermittent vomiting. Physical examination revealed multiple mammary nodules. A complete left chain mastectomy was performed and submitted for histopathologic examination.

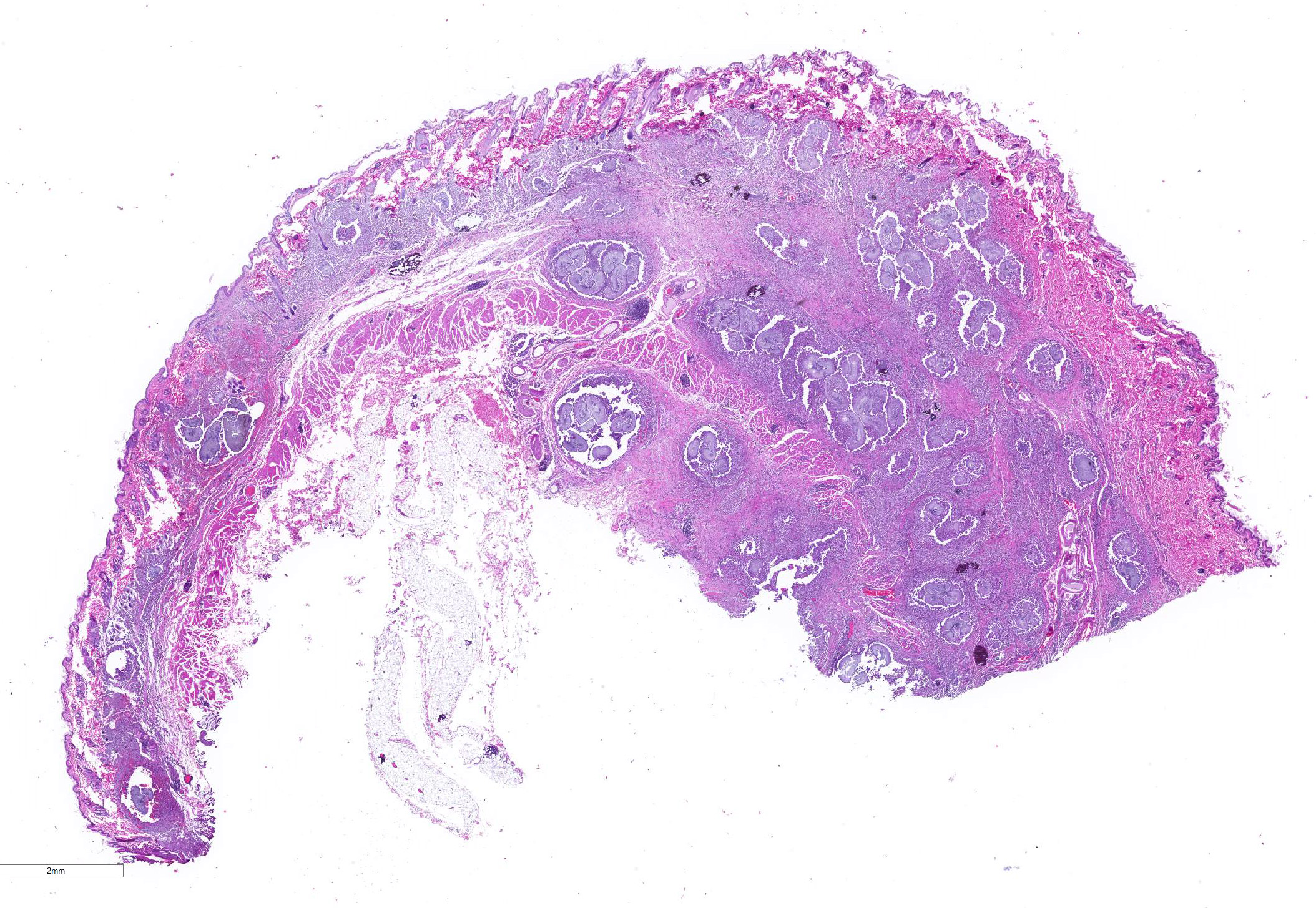

Gross Pathology: Two sections of formalin-fixed pigmented haired skin with subcutis and mammae. The dermis and subcutis was markedly thickened and nodular around the teats. When sectioned, the tissue was firm and mottled light tan and brown.

Laboratory results:

Bloodwork and cytology was performed by the referring veterinarian. Bloodwork revealed elevated liver values. Cytology of a mammary nodule was suggestive of adenocarcinoma.

Microscopic Description:

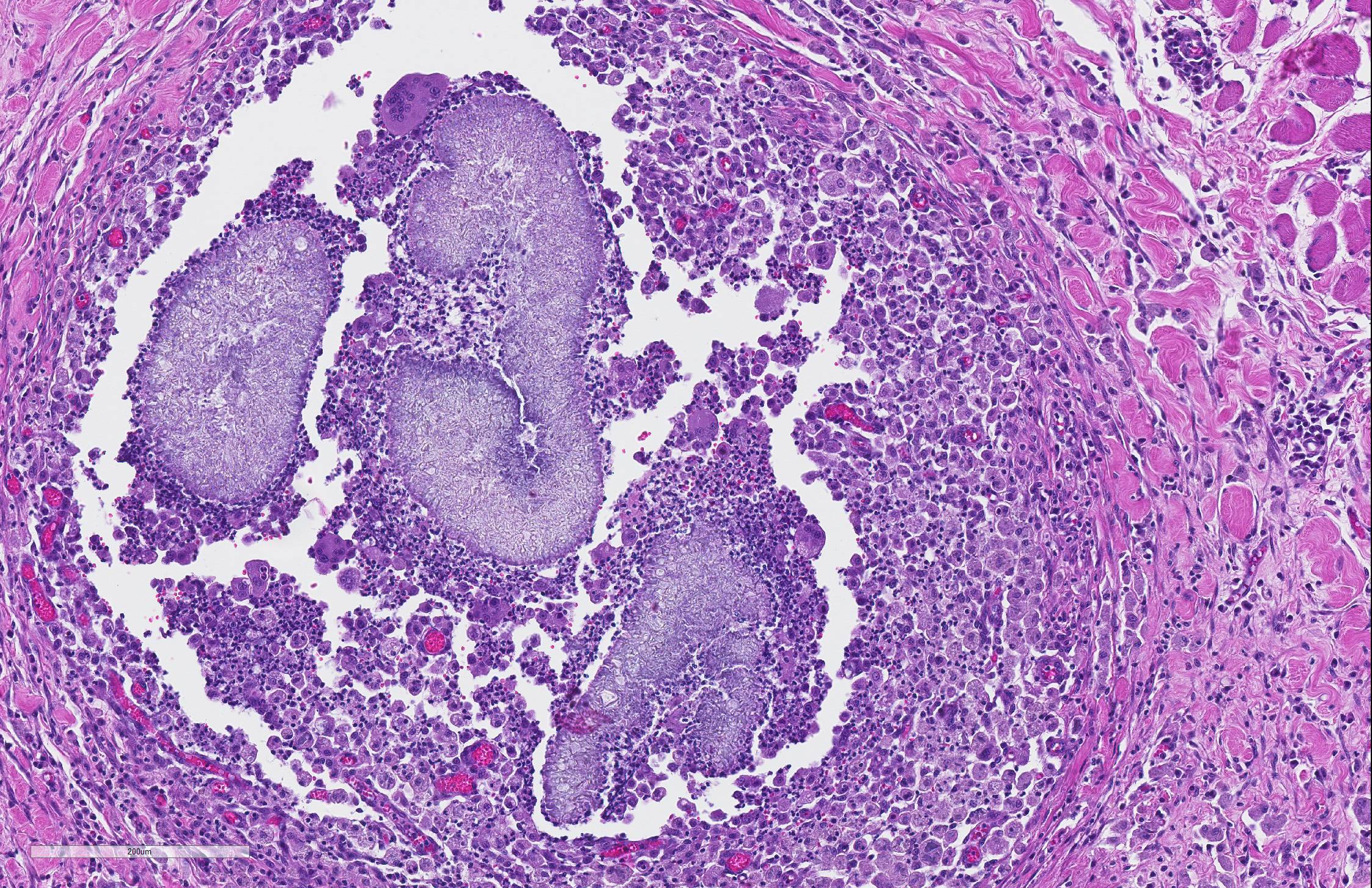

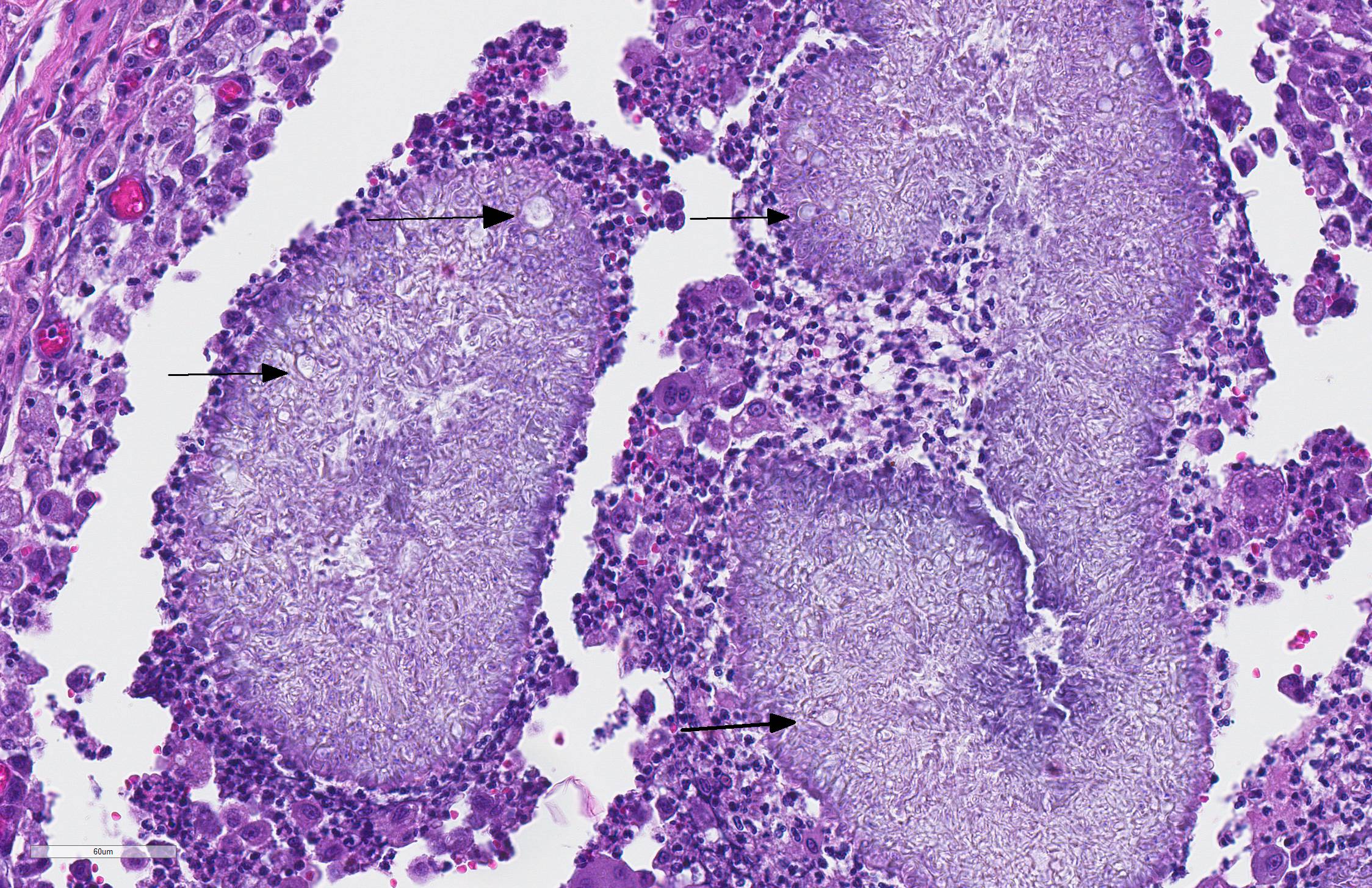

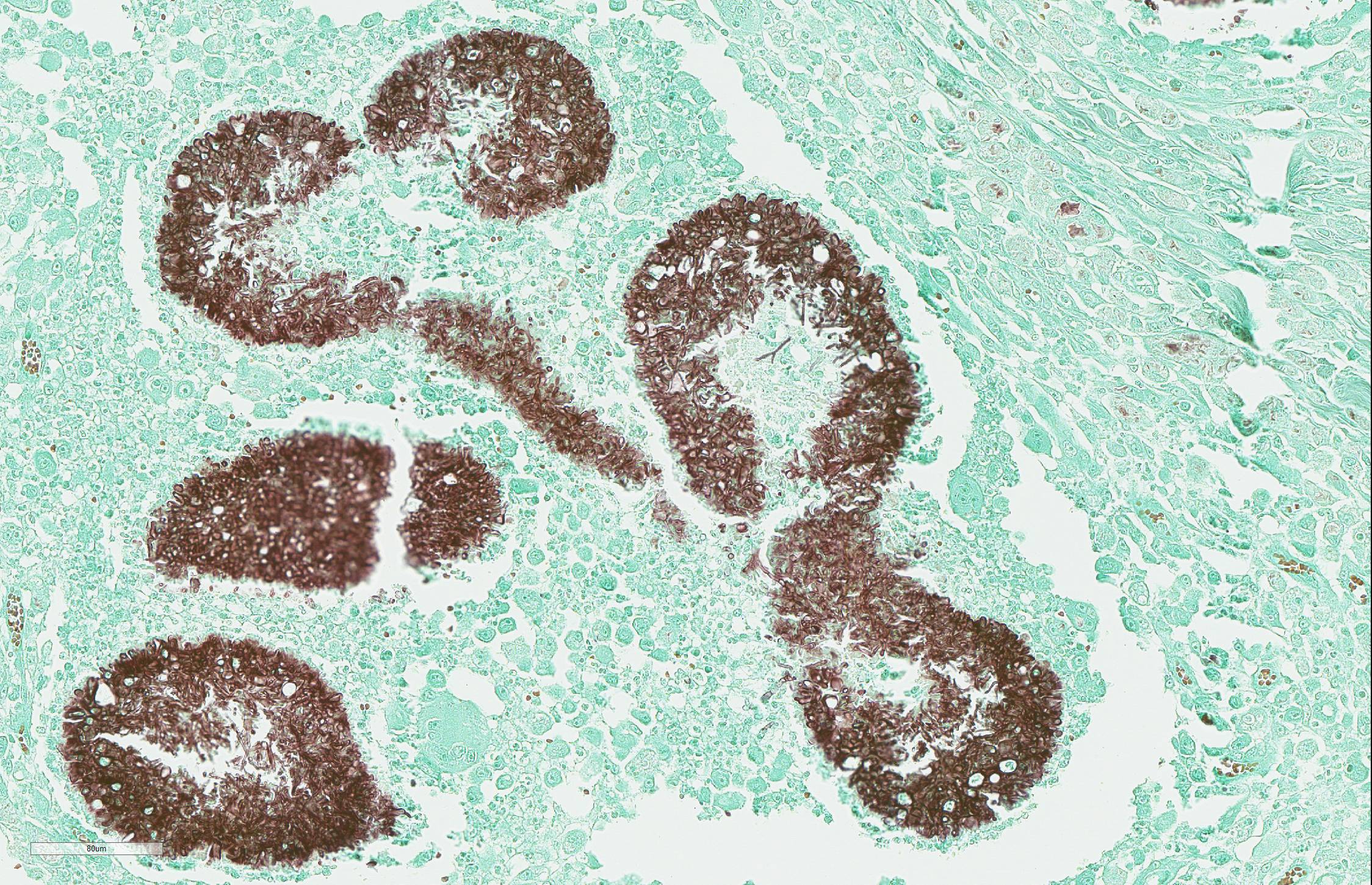

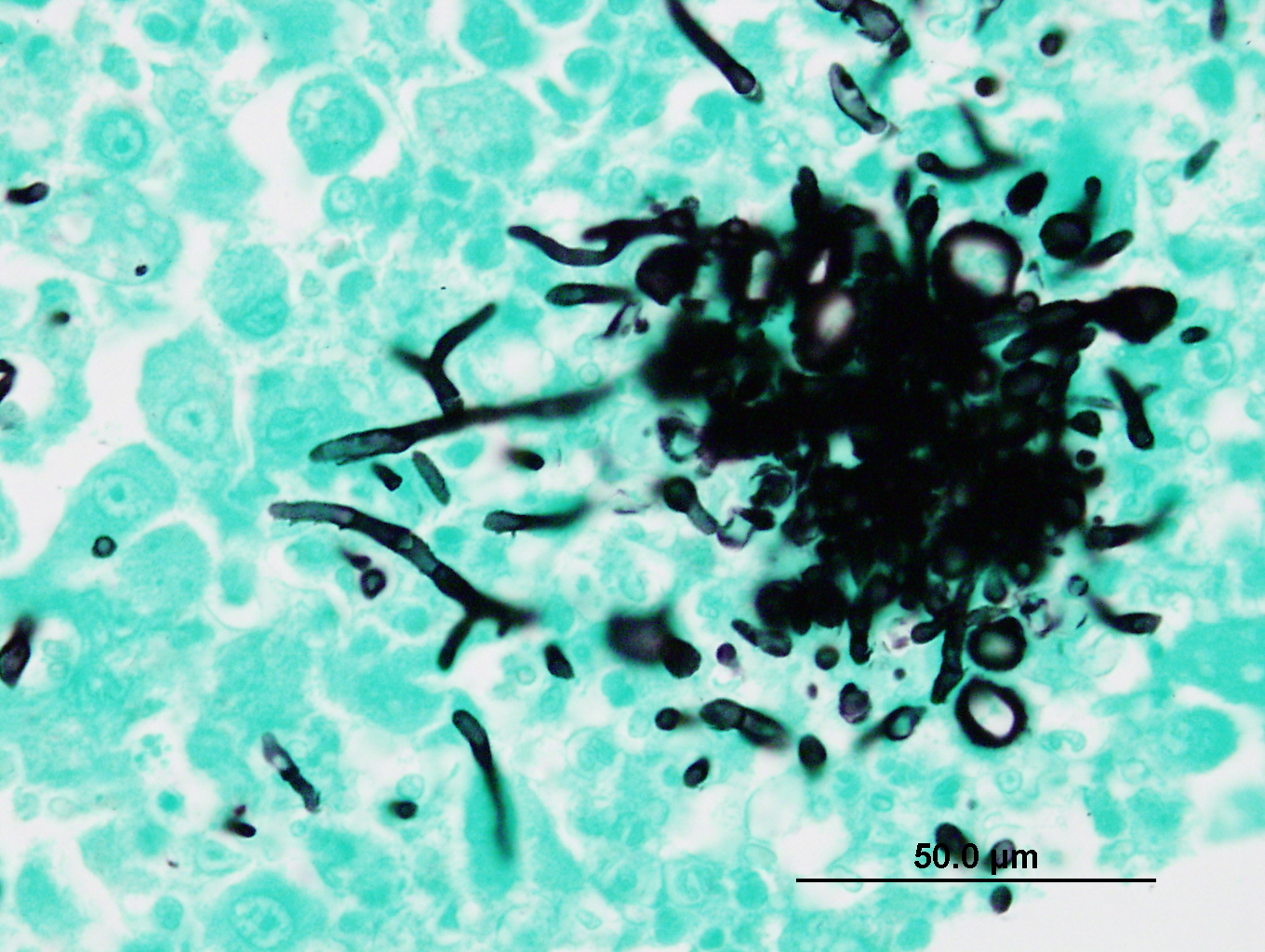

The sections of lightly pigmented, haired skin have intense nodular and diffuse infiltrates extending from the deep dermis into the subcutis that often efface the dermis and subcutis. The nodules are composed of large mats of hyphae embedded in granular eosinophilic material that is slightly radiating and forms irregularly-shaped tissue grains (Splendore-Hoeppli material). The hyphae are often tangled and irregularly arranged, are approximately 5-7 micrometers in diameter, have parallel walls with frequent bulbous dilations, are septate and have rare acute-angle branching. The mats of hyphae and Splendore-Hoeppli material are surrounded by many foamy and epithelioid macrophages, Langhans and foreign body-type multinucleated giant cells and neutrophils. Some large nodules have a thin peripheral rim of fibrous tissue containing moderate numbers of fibroblasts. Many macrophages and multinucleated giant cells are moderately to markedly distended with abundant amorphous to globular material that stains intensely eosinophilic with a PAS histochemical stain and black with GMS histochemical staining (presumptive dermatophyte remnants). On H&E sections this phagocytized material is clear with pale eosinophilic hyphal margins. Within lower numbers of macrophages and multinucleated giant cells there are fragments of hyphae with parallel walls, bulbous dilations, and septae. Also within the nodular to diffuse infiltrate there are often small moderate-sized aggregates of mineralized material that contain abundant, similar hyphae. Areas of mineralization are most common within the superficial margins of the infiltrate. Within tissue that is not effaced, there are nodules composed of many lymphocytes and few plasma cells and macrophages surrounding blood vessels in the deep dermis and subcutis. There is a clear line of demarcation between the nodular to diffuse infiltrate within the deep dermis and superficial dermis. Within the superficial dermis there are perivascular and interstitial infiltrates composed of lower numbers of lymphocytes, plasma cells, mast cells and few neutrophils. The overlying epidermis has an irregular, papillated appearance and there is mild to marked basket-weave and compact orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis. PAS and GMS histochemical stains do not reveal hyphae along the epidermal surface or within follicles.

Contributor Morphologic Diagnosis:

Dermatitis, pyogranulomatous, multifocal and focally extensive, chronic, severe, with myriad fungal hyphae embedded within Splendore-Hoeppli material, deep dermis and subcutis of the ventral abdomen

Contributor Comment: The histologic findings were most consistent with dermatophytic pseudomycetoma. Dermatophytic pseudomycetomas are deep dermal to subcutaneous atypical dermatophyte infections with nodules that frequently ulcerate and form draining tracts. Pseudomycetomas have been reported to range from 1-8 cm in diameter and can mimic neoplasia, as in this case.4,5,7 Initially, the nodules are small and non-painful, so disease is often chronic before detections, particularly in long-haired cats. Dermatophytic pseudomycetoma is most commonly caused by Microsporum canis and has almost exclusively been reported in Persian cats and to lesser extent Himalayan cats.5,7,9 The lesions have been reported to occur with or without a history of skin trauma and occur more commonly on the head, neck, dorsum, tail, flanks or limbs,5,7 and lesions on the ventral abdomen are uncommonly reported.5 The granules present within the tissue and fistulous tracts have been described as white, yellow, or light brown.5

The histomorphology of hyphae in tissue alone is an inaccurate method to identify fungi/dermatophytes and culture and/or PCR are needed for definitive diagnosis. Unfortunately in this case, fresh tissue was not obtained at the time of surgery, as neoplasia was suspected, and an infectious etiology was not on the referring veterinarianâs differential list because of the clinical presentation and fine needle aspirate results. We did submit formalin-fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) tissue for pan-fungal PCR, and despite the large numbers of hyphae within the lesions, PCR failed to identify the organisms. In a case report of four cats with dermatophytic pseudomycetomas, PCR performed using FFPE tissue failed to identify the dermatophytes one of the two cases in which Microsporum canis was confirmed with culture, and in two of the cases that had characteristic lesions, but in which tissue was not submitted for culture.5

Dermatophytic pseudomycetomas are very similar to true eumycotic mycetomas as the organisms are present in tissue as grains or granules, however there is a difference in the formation of the granules in that there is less amorphous eosinophilic material (cement-like substance) within the grains in mycetomas, and more Splendore-Hoeppli material is present in pseudomycetomas.7,9 Pseudomycetomas are formed by dermatophytes and bacteria that are not members of the Actinomycetales order.9

The pathogenesis of dermatophytic pseudomcyetoma is unclear, and most reported cases lack the history of trauma preceding the development of the lesions. It is believed that furunculosis resulting from typical dermatophyte infections may lead to the migration of dermatophyte hyphae into the deep dermis and subcutis, followed by development of pseudomycetomas.5,6 An underlying immunosuppression or a selective immunodeficiency is thought to underlie the susceptibility of Persian cats to conventional dermatophytosis and dermatophytic pseudomycetoma.5,7 Others have hypothesized that long-haired cat breeds, such as Himalayan and Persian cats may be more susceptible due to incomplete grooming of the hair coat and long hair, which may predispose to more chronic dermatophytosis and furunculosis.5,6 In this case, although there was a chronic history of dermatophytosis in this cat, there was no histologic evidence of dermatophytosis in the dermis, epidermis and hair follicles. There has been one case report, of intra-abdominal dermatophytic granulomatous peritonitis in a Persian cat.4 The authors in this case report hypothesized that generalized dermatophytosis at the time the cat was spayed may have led the inoculation of dermatophyte hyphae in to the abdomen, despite the surgery occurring several years prior to diagnosis. The significant weight loss, vomiting, and increasing liver values in this cat, raises the possibility of systemic involvement. One thought we had was that the body confirmation of this cat breed with very short legs could have been a predisposing factor for the development of these pseudomycetomas, possibly due to traumatic furunculosis that could be more common in a Munchkin cat with chronic dermatophytosis, due to an increased likelihood of contact to the ventral abdomen against contact surfaces during play, etc due to the short stature of the breed.

Treatment of dermatophyte pseudomycetomas in cats is difficult with variable responses to anti-fungal medications alone.4,5,6,10 It has been suggested that wide surgical excision and concurrent treatment with oral itraconazole prior to and after wide surgical excision are beneficial in the treatment of dermatophytic pseudomycetoma with results ranging from long-term disease free interval prior to recurrence to presumptive clinical cure of up to 2 years and 8 months at the time of publication.5 In another paper the use of oral terbinafine resulted in resolutions of dermatophytic mycetomas in two cats. One catâs (Persian) clinical signs require continual pulse therapy of the drug as the lesions recurred after compete discontinuation. The other cat had no recurrence for 28 months after discontinuation of the medication at the time of publication.2 Dermatophytic pseudomycetoma has been rarely been reported in dogs, with reported cases occurring in a Manchester Terrier, two Yorkshire Terriers, and a Chow Chow.1,7

Contributing Institution:

University of Florida

College of Veterinary Medicine

Department of Comparative, Diagnostic, and Population Medicine

JPC Diagnosis: Haired skin and subcutis: Pyogranulomas, multiple, with dermal fibrosis, Splendore-Hoeppli material, and numerous intradermal fungal hyphae (pseudomycetoma).

JPC Comment: The contributor has done an outstanding job on describing this uncommon finding in cats, which is even more rare in other veterinary species. The terminology of this condition continues to be confusing, with mycetoma, eumycotic mycetoma, actinomycotic mycetoma, bacterial mycetoma, and pseudomycetoma all floating around in the liteature.

A mycetoma cotains three distinguishing features: 1) the formation of a nodular fibrotic inflammatory lesion, 2) formation of draining tracts, and 3) the grossly visible presence of fungal or bacterial grains.3,4 When bacteria are at the center of the grains, the term bacterial mycetoma may be applied.11 More specific bacterial terms may be utilized, such as "actinomycotic mycetoma" in cases of subcutaneous infection with Actinomyces, Nocardia, and Actinomadura spp.2 Eumycotic mycetomas are caused by species of true fungi (non-dermatophyte), which are enmeshed in "grain cement" which contains melanin, proteins, and lipids.2

The usage of the term pseudomycetoma is somewhat less well-defined. In humans, pseudomycetomas are smaller, do not form draining tracts, and are often on parts of the the body other than the feet.3 Bacterial cultures are usually negative. The material that binds the hyphae into grains is Splendore-Hoeppli material, which may be composed of antigen-antibody complexes, major basic protein, or both.3 In the veterinary literature, the term pseudomycetoma is used to describe mycetomas resulting from dermatophyte infection of subcutaneous tissue, while in other publications the term is used to describe fungal species that have been traumatically implanted (most of which are dermatophytes as well). Many authors now prefer the term "dermatophytic pseudomycetoma" which provides both agent and method of traumatic implantation to deep tissues.6,7,8 It should be pointed out that dermatophytic pseudomycetoma is a separate (and disparate) disease from superficial dermatophytic infection.3

In humans, mycetomas are considered endemic in certain parts of the world within the so-called "mycetoma belt" which included India, Sudan, and Mexico.2 These forms of deep fungal infection are true mycetomas, without representation from dermatophytes. The mycetomas in question are most often seen in the feet, with disfiguring lesions, multiple draining sinuses, and variably colored and shaped grains. Deep surgical excision of of grains under aseptic conditions is important in diagnosis, as direct visualization and culture of fungal hyphae within the grains is paramount.2 Grains that wash out through draining tracts are not considered appropriate for diagnosis. Serodiagnostic test have proved valuable in certain instances, and PCR testing of grains shows great promise in parts of the "mycetoma belt" where they have been employed.2

The moderator also noted the bulbous swellings on the end of the hyphae within the deep dermis. While usually seen in dermatophytic mycelia, these "chlamydiospore-like" structures are also seen in pseudomycetomas for unknown reasons. In vary rare cases, in Persian cats, the sexual stage of Microsporum canis, Arthrosporum canis, has been isolated.

References:

1. Abramo F, Vercelli A, Mancianti F. Case report: two cases of dermatophytic pseudomycetoma in the dog: an immunohistochemical study. Vet Dermatol. 2001;12:203-207.

2. Ahmed, AA, van de Sande W, Fahal AH. Mycetoma laboratory diagnosis: review article. PLoS Neg Trop Dis 2017: 11(8): e0005638.

3. Berg JC, Hamacher KL, Roberts GD. Pseudomycetoma caused by Microscopum canis ina n immunosuppressed patient: a case report and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol 2007: 34:431-434.

4. Black SS, Abernathy TE, Tyler JW, et al. Intra-abdominal dermatophytic pseudomycetoma in a Persian cat. J Vet Intern Med. 2001;15:245-248

5. Bonifaz A, Tirado-Sanchez A, Calderon L, Saul M, Araiza J, Hernandezz M, Gonzalez GM, Pnce RM. Mycetoma: Experience of 482 cases in a single center in Mexico. PLos Negl Trop Dis

6. Chang, Shih-Chieh, et al. Dermatophytic pseudomycetomas in four cats. Vet Dermatol. 2010;22:181-187.

7. Duangkaew, L, et al. Cutaneous blastomycosis and dermatophytic pseudomycetoma in a Persian cat from Bangkok, Thailand. Medical Mycology Case Reports 15 (2017) 12-15.

8. Giner J, Bailey J, Juan-Salles C, Joiner K, Martinez-Romero EG, Oster S. Dermatophytic pseudomycetomas in two ferrets. Vet Derm 2018: 29:452-e154.

9. Gross TL, et al. Skin Diseases of the Dog and Cat: Clinical and Histopathologic Diagnosis. 2nd Ed. 288-291. 2005.

10. Mauldin, EA and Peters-Kennedy, J. Integumentary System. In Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmerâs Pathology of Domestic Animals. Edited by: M. Grant Maxie Vol. 1, 6th Ed. 2016, Elsevier. pp. 653-659.

11. Martoreall, Jaime, Gallifa N, Fondevila D, Rabanal RM. Bacterial pseudomycetoma in a dwarf hamster. Eur Soc Vet Derm 2006: 17:449-452.

12. Nuttall TJ, German AJ, Holden SL, Hopkinson C, and McEwan NA Successful resolution of dermatophyte mycetoma following terbinafine treatment in two cats. The Authors Journal Compilation ESVD and ACVD. 2008;19:405-410.