Wednesday Slide Conference, Conference 2, Case 2

Signalment:

12.9 year-old FS Yorkshire terrier dog (Canis lupus familiaris)

History:

The dog has a history of tracheal collapse and coughing. Over the previous 6 months, the owner noted increased respiratory effort and restlessness. Thoracic radiographs indicated a soft tissue opacity in the cranial thorax along with mild cardiomegaly and a mild, diffuse bronchointerstitial pattern in the lungs. An echocardiogram indicated myxomatous mitral valve degeneration and second-degree AV block, as well as confirming a lobulated structure in the cranial mediastinum. Bloodwork was unremarkable. The mass was removed and submitted for histopathology.

Gross Pathology:

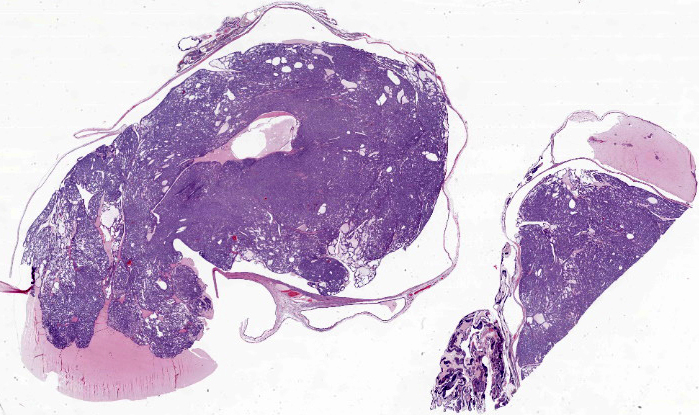

The mass received measured 3.9 x 2.8 x 1.6 cm and was mottled tan to dark purple, multinodular, and semi-firm to firm.

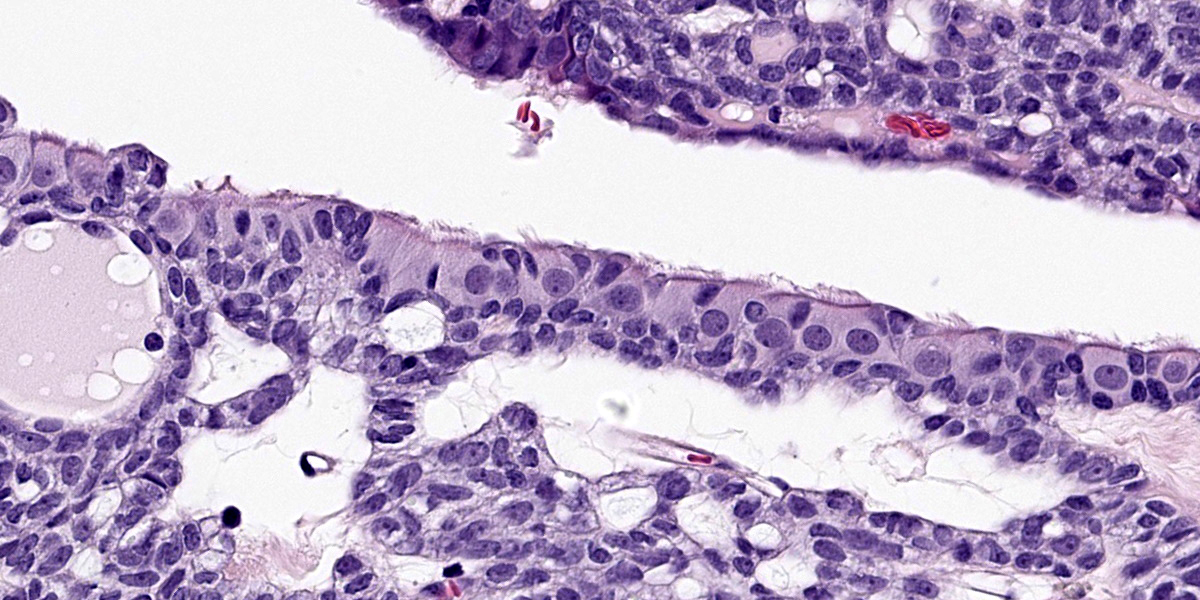

Microscopic Description:

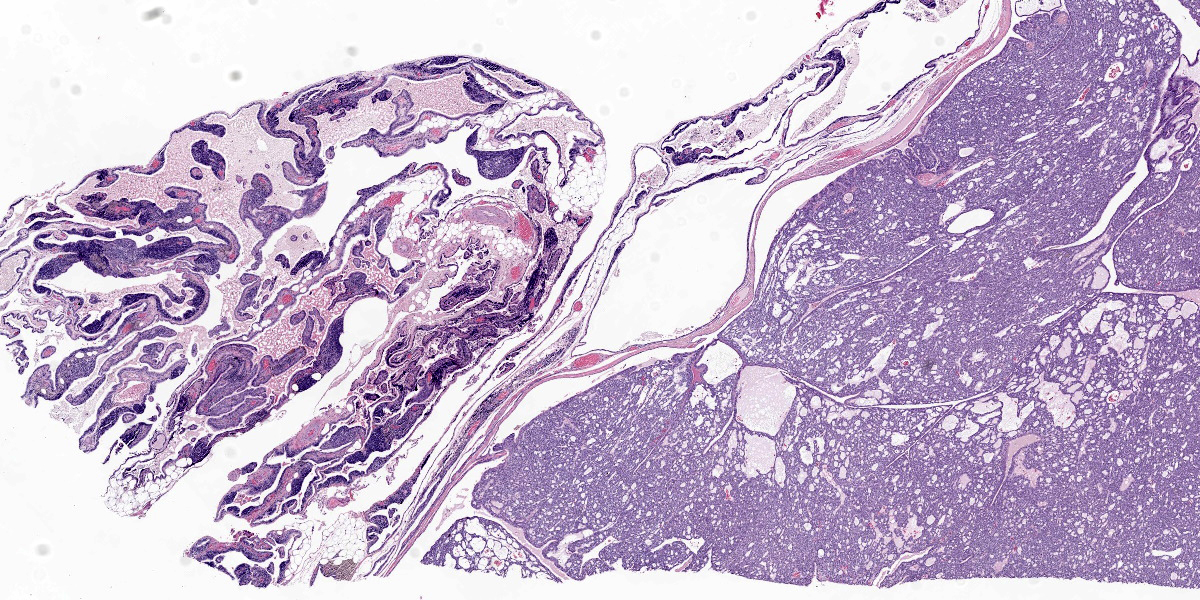

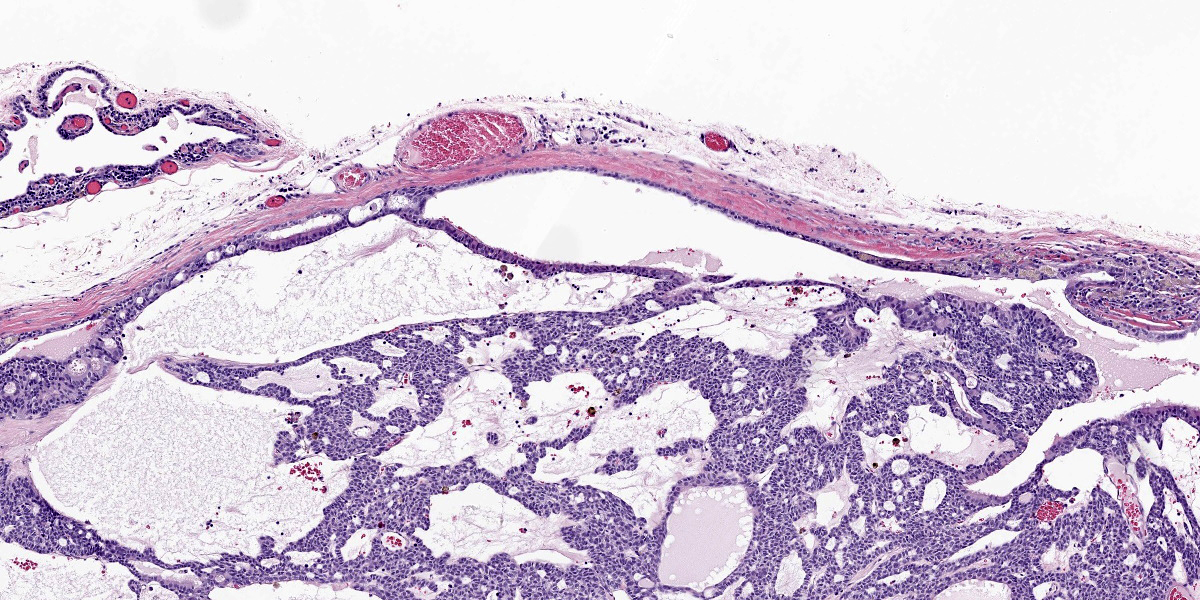

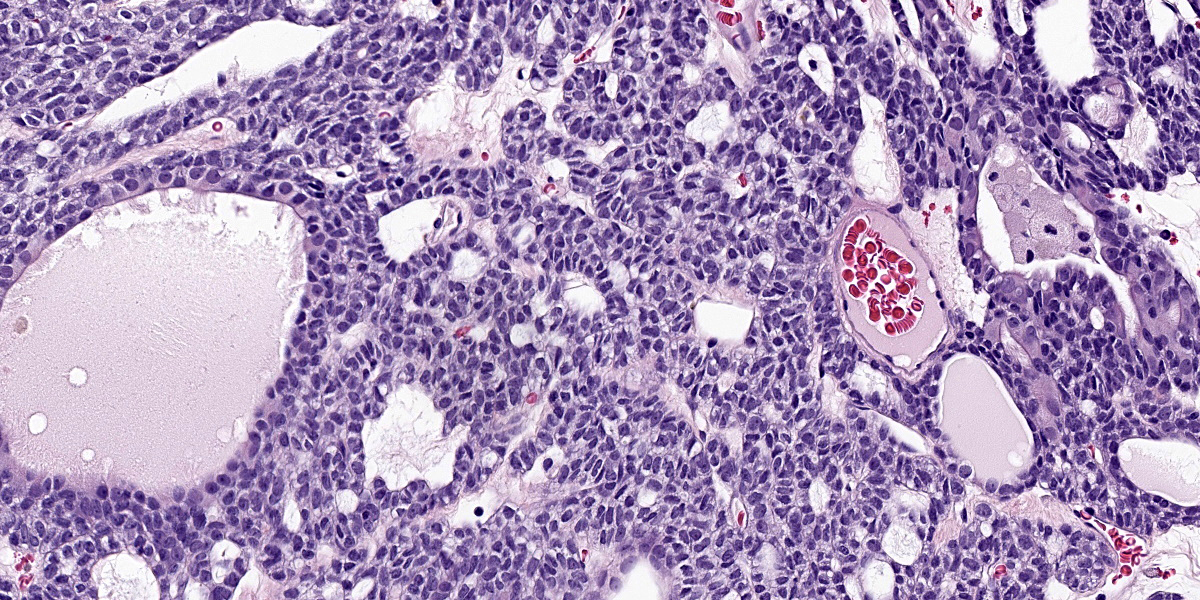

There is minimal residual thymic tissue present, with only minimal lymphoid cells present. There are several, variably sized cysts, containing eosinophilic or clear space and which are lined by ciliated cuboidal epithelium. Within the lumen of several large cysts, with retained cyst lining epithelium, there are mass effects, produced by proliferations of similar epithelial cells to form solid islands, sheets, rare tubules and ducts, some of which contain eosinophilic fluid. The neoplastic cells have moderate amounts of lightly vacuolated cytoplasm, round to ovoid vesicular nuclei, with small to no nucleoli. There is moderate anisokaryosis and anisocytosis. Mitoses are 2 per 10 high power fields (400x).

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Cranial mediastinal mass: Branchial cysts with transformation to branchial carcinoma

Contributor’s Comment:

Branchial cysts arise from remnants of pharyngeal (branchial) pouches, which are a series of 4 to 5 bilateral embryonic endodermal evaginations that project laterally between the pharyngeal arches. The pharyngeal pouches and clefts contribute to the formation of the thymus (from the third pharyngeal pouch), parathyroid gland, pharyngeal tonsils, and middle and external ear.7 Epithelia migrate caudally from the submandibular region, down the neck, and into the cranial mediastinum during development, occasionally leaving remnants at points along this tract that can develop into cysts.5

Cervical and mediastinal branchial cysts have been reported in dogs, but there are few reports of thymic branchial cysts in veterinary medicine2,5 and even fewer reports of neoplastic transformation.5,8 Some of these thymic cysts may be attributed to cystic proliferation of thymic reticular cells rather than remnants from the third pharyngeal pouch. Branchial cysts are distinguished by the presence of variably squamous to ciliated lining epithelial cells with no external opening.9 Thymic branchial cysts are typically benign and more common in older dogs, but can become space-occupying, leading to cranial vena cava syndrome and pleural effusion.5 In a report of a dog with malignant transformation of a thymic branchial cyst to a carcinoma, pulmonary metastases were present as well.4

In humans, suspected malignant transformation of cervical branchial cysts has been reported with a variety of terms, including branchiogenic carcinoma, branchioma or malignant branchioma. The nomenclature and origin of these masses remains under debate. It has been suggested that these masses are metastases to the cyst from an unrecognized primary tumor, most commonly oropharyngeal carcinomas such as tonsillar carcinoma.3 Overall, these tumors are considered exceptionally rare in humans.1

Differential diagnoses for a cranial mediastinal mass in dogs include thymoma, thymic lymphoma, thymic carcinoma, thymofibrolipoma, chemodectoma, ectopic thyroid tumor, schwannoma, thymic hyperplasia, abscess, or granuloma. Given its rarity and a lack of definitive immunohistochemical markers, branchial cyst carcinomas should be considered a diagnosis of exclusion.

Contributing Institution:

University of Wisconsin-Madison

School of Veterinary Medicine

Department of Pathobiology

2015 Linden Dr

Madison WI 53703

https://www.vetmed.wisc.edu/departments/pathobiological-sciences/

JPC Diagnosis:

Thymic remnant: Branchial carcinoma arising in branchial cyst.

JPC Comment:

This particular case is somewhat challenging to recognize the salient features and arrive at an exact diagnosis. The large cystic spaces, the small numbers of lymphocytes, and ciliated cuboidal epithelium are all helpful to note, especially starting from the position shown in figure 2-2. Ciliated epithelium (figure 2-5) is commonly seen in respiratory and reproductive epithelium, though the other two facets don’t quite fit with those interpretations. Cilia are also a component of branchial pouch epithelia8,9 – together with the CD3 positive lymphocytes, the tissue in section most resembles

a cyst of branchial pouch origin which is located within the thymic remnant of an older dog. That said, the eosinophilic fluid in the background could easily be mistaken for thyroidal colloid at first glance as well. Conference participants as a whole thought that the tissue was ovarian and that the cystic fluid partially resembled Call-Exner bodies of a granulosa cell tumor (figure 2-4) and explained the ciliated epithelium as part of the oviduct. Though these interpretatoins were not ultimately correct, they were good ruleouts for an exquisitely unusual entity. Although branchial cysts have been reported in veterinary medicine, malignant transformation is rare4,7 In this case, Dr. Williams felt that there was supporting evidence of transformation of the cyst lining itself into a discrete neoplasm (figure 2-3) within the section presented.

An important differential in this case is multiple thymic cyst and thymic origin neoplasia though we also considered the possibility of a neuroendocrine or thyroid tumor too. The animal in this case reportedly had a mass within the cranial thorax which was localized to the mediastinum via echocardiography. In addition to CD3, we also ran IHCs for pancytokeratin, TTF-1, chromogranin, and synaptophysin. Pancytokeratin was diffusely and strongly cytomembranously immunoreactive while chromogranin, synaptophysin were diffusely negative which was consistent with a cystic epithelial tumor. TTF-1 was not immunoreactive in the cells of interest, which excluded a thyroid tumor. Likewise, the malignant neoplastic cells the contributor describes lack squamous differentiation and a high (>10) mitotic rate that is associated with thymic carcinomas.9 For these reasons, we favor a branchial cyst carcinoma arising in a thymic remnant for this case. Lastly, branchial cyst remnants were previously (briefly) covered in Conference 7, Case 2, 2017-2018 – we suspect it may be some time before we see this entity again.

References:

- Bradley PT, Bradley PJ. Branchial cleft cyst carcinoma: fact or fiction? Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;21:118-123

- Day MJ. Review of thymic pathology in 30 cats and 36 dogs. J Small Anim Pract. 1997;38:393-403.

- Jereczek-Fossa BA, Casadio C, Jassem J, et al. Branchiogenic carcinoma – conceptual or true clinic-pathological entity? Cancer Treat Rev. 2005;31:106-114.

- Levien AS, Summers BA, Szladovits B, Benigni L, Baines, SJ. Transformation of a thymic branchial cyst to a carcinoma with pulmonary metastasis in a dog. J Small Anim Pract. 2010;51: 604-608.

- Nelson LL, Coelho JC, Mietelka K, Langohr IM. Pharyngeal pouch and cleft remnants in the dog and cat: a case series and review. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2012;48:105-112.

- Rosol TJ, Gröne A. Endocrine Glands In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Elsevier; 2016:310.

- Sano Y, Seki K, Miyoshi K, Sakai T, Kadosawa T, Matsuda K. Mediastinal basaloid carcinoma arising from thymic cysts in two dogs. J Vet Med Sci. 2021;83(5): 876-880.

- Uzal FA, Plattner BL, Hostetter JM. Alimentary System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy & Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 2. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:22.

- Valli VEOT, Kiupel M, Bienzle D, Wood RD. Hematopoietic System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy & Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 3. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:151-157.