Signalment:

Gross Description:

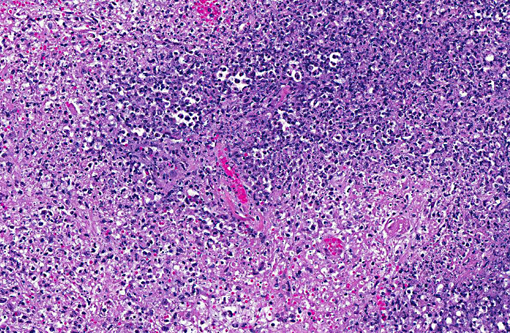

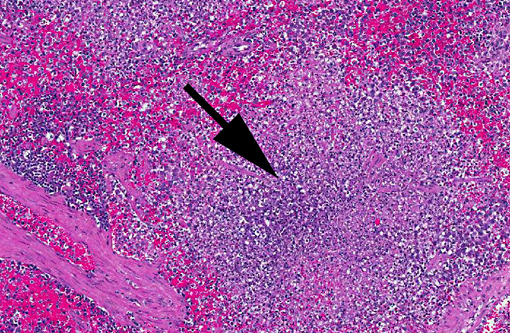

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Hematocrit: decreased (21)

ALT: increased

Albumin: decreased

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Francisella tularensis is a gram-negative bacterial rod and a facultative intracellular pathogen of macrophages. The organism is difficult to grow in artificial media and the diagnosis is best confirmed by PCR.

Francisella tularensis is the cause of the disease tularemia. Tularemia has a worldwide distribution and affects a variety of mammals, birds, amphibians and fish. The organism is maintained in the environment by various terrestrial and aquatic mammals, primarily rabbits and rodents, and is transmitted by a variety of arthropods including ticks, mites, blackflies, fleas, mosquitoes and lice.(2) The organism may also be transmitted by contact with infected vertebrates, by inhalation of feces-contaminated dust, or ingestion of insufficiently cooked infected carcasses. Human infections usually result from skinning or dressing rabbits, and rabbits are the source of infection in 90% of human cases.(4)

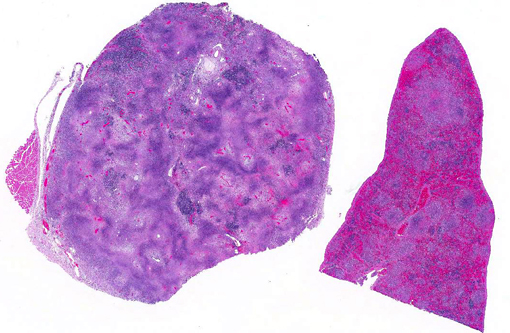

Gross lesions of tularemia are multifocal white spots in liver, spleen and lymph node varying in size from pinpoint to several millimeters. Microscopic lesions are multifocal to confluent areas of necrosis with a mild influx of macrophages and neutrophils.

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Spleen: Splenitis, necrotizing, multifocal to coalescing, severe.

2. Lymph nodes: Lymphadenitis, necrotizing, multifocal to coalescing, severe.

Conference Comment:

F. tularensis can pass transovarially within tick vectors, which are infected for life.(3) Additionally, the bacterium can survive for weeks to months in water, soil, and decaying animal carcasses.(5) Bacteria are typically inoculated into the host during tick feeding/defecation or following ingestion of infected rabbits or rodents. Dogs appear to be fairly resistant while cats and rabbits are susceptible. The infectious dose can be quite low; inhalation or parenteral inoculation of 10 to 50 colony-forming units can induce clinical disease, while 108 colony-forming units are required for oral infection. F. tularensis persists within macrophages where it inhibits phagosome-lysosome fusion; the bacterial capsule is thought to be important in intracellular survival.(1,3) Necrosis generally centers upon lymphoid tissue within the spleen and lymph nodes, although lesions within the liver and lungs (especially if bacteria are inhaled) are also commonly described.(3,5) The gross lesions associated with F. tularensis (foci of splenic, lymph node and hepatic necrosis and/or pyogranulomatous inflammation) are indistinguishable from lesions associated with yersiniosis. Histologically, Yersinia spp. often form large colonies, while F. tularensis coccobacilli are typically found within macrophages,(6) although individual bacterial were not readily apparent in this case.

References:

1. Biberstein EL, Hirsh DC. Francisella tularensis. In: Hirsh DC, Zee YC, eds. Veterinary Microbiology. Malden, MA: 1999:285-286.

2. Ellis J, Oyston CF, Green M, Titball RW. Tularemia. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2002;15:631-646.

3. Greene CE. Francisella and Coxiella infections. In: Greene CE, ed. Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Saunders; 2012:476-482.

4. Lamps LW, Havens JM, Anders S, Page DL, Scott MA. Histologic and molecular diagnosis of tularemia: a potential bioterrorism agent endemic to North America. Modern Pathology. 2004;17:489-495.

5. Spagnoli ST, Kuroki K, Schommer SK, Reilly TJ, Fales WH. Pathology in practice. Francisella tularensis. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2011;238(10):1271-1273.

6. Valli VEO. Hematopoietic system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 3. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:297-299.