Signalment:

Rabbit – Lionhead Oryctolagus cuniculus; Male neutered, 4.4 years old

History:

Two-week history of progressive hyperkeratosis/skin crusting/alopecia. Skin scraping negative for mites. The rabbit clinically had severe otitis externa/media, bilateral corneal ulcers, dyspnea, hypothermia, early GI stasis, severe left sided dental disease, suspected tear duct obstruction, severe pododermatitis, severe urine scalding. Euthanized and submitted for postmortem evaluation.

Gross Pathology:

Submitted is the body of a 2.1 kg, white, male neutered Lionhead rabbit. He is in good body condition with ample subcutaneous fat and symmetrical muscling. There is scaling of the skin over the majority of the body surface, most pronounced on the hocks, the dorsal antebrachia, the dorsal surface of the neck and base of the ears extending over the lateral neck on both sides and ventrally to the level of the sternum. Occasionally, there is hair loss associated with this scaling over the antebrachia and the dorsal and lateral neck. There is marked scaling of the skin around the mouth as well as surrounding the eyes with thick accumulations of dry, yellow to brown crusts in these areas. These areas are also alopecic. There is extensive fecal staining of the perianal area and hindlimbs with alopecia of the medial surface of both proximal hindlimbs. Both eyes have an approximately 2.0 mm white opacity centrally on the corneal surface.

There is approximately 2 mL of serosanguineous fluid within the thoracic cavity which contains rare soft, yellow to clear, irregular serous clots. The lungs appear diffusely, mildly atelectatic. The cranial mediastinum is expanded by a dark red to tan, irregular, soft mass measuring approximately 4 cm by 3 cm by 2 cm which displaces the heart caudally and the lungs caudodorsally. This mass is adherent to the ventral thoracic wall and the cranial surface of the pericardial sac. The mass is immediately adjacent to the aorta and cranial vena cava which run over the surface of the mass but are not incorporated into it. On cut section the mass is mottled dark red to tan with multiple cystic spaces containing approximately 1 mL of serosanguineous fluid. There is approximately 1 mL of serosanguineous fluid in the pericardial sac, but the inner surface is intact and there is no association between the mediastinal mass and the heart. The heart appears subjectively enlarged, occupying approximately one quarter of the thoracic cavity. There is subjective dilation of both ventricles but the left:right ventricular ratio is within normal limits. There is an enhanced zonal pattern in the liver which appears diffusely mottled yellow and red. This pattern continues throughout the parenchyma on cut section. The right renal pelvis contains a small amount of red material (rule out hemorrhage vs artifact). The bladder contains a moderate amount of slightly turbid yellow urine. It can be expressed with minimal digital pressure. There are sharp spurs on the lingual aspects of the mandibular cheek teeth and on the buccal aspects of the maxillary cheek teeth, slightly more severe on the left side. There is mild stenosis of the vertical canal of both ears due to thickening and scaling of the skin. There are plugs of white to tan soft exudate within both vertical canals. The tympanic bulla, middle ear, and inner ear appear grossly unremarkable. The nasal sinuses appear grossly unremarkable.

Laboratory Results:

No laboratory results reported.

Microscopic Description:

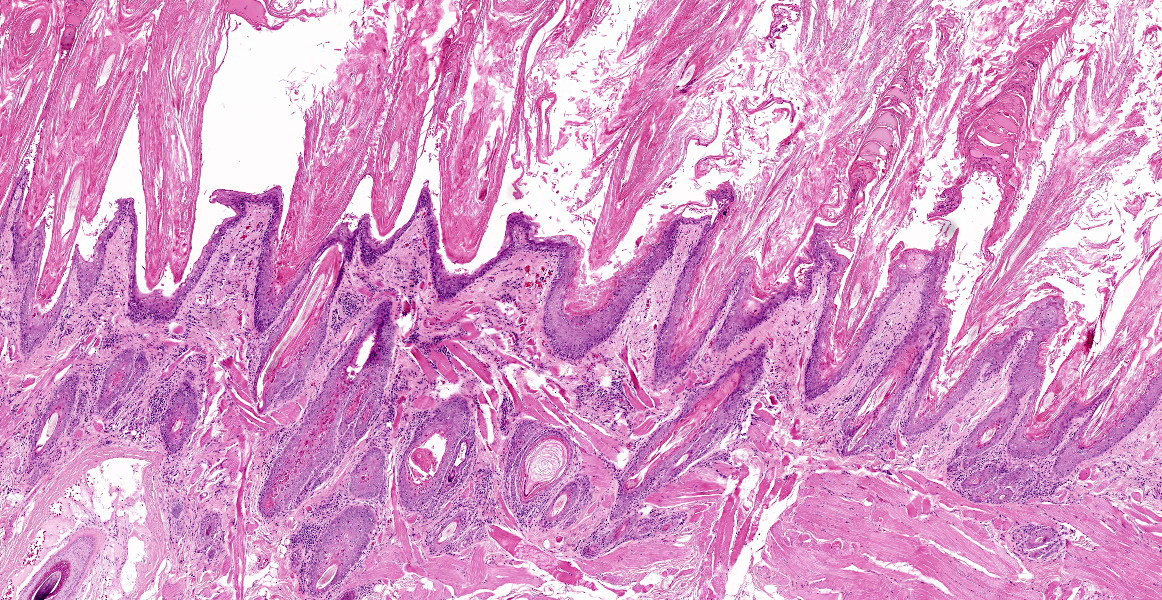

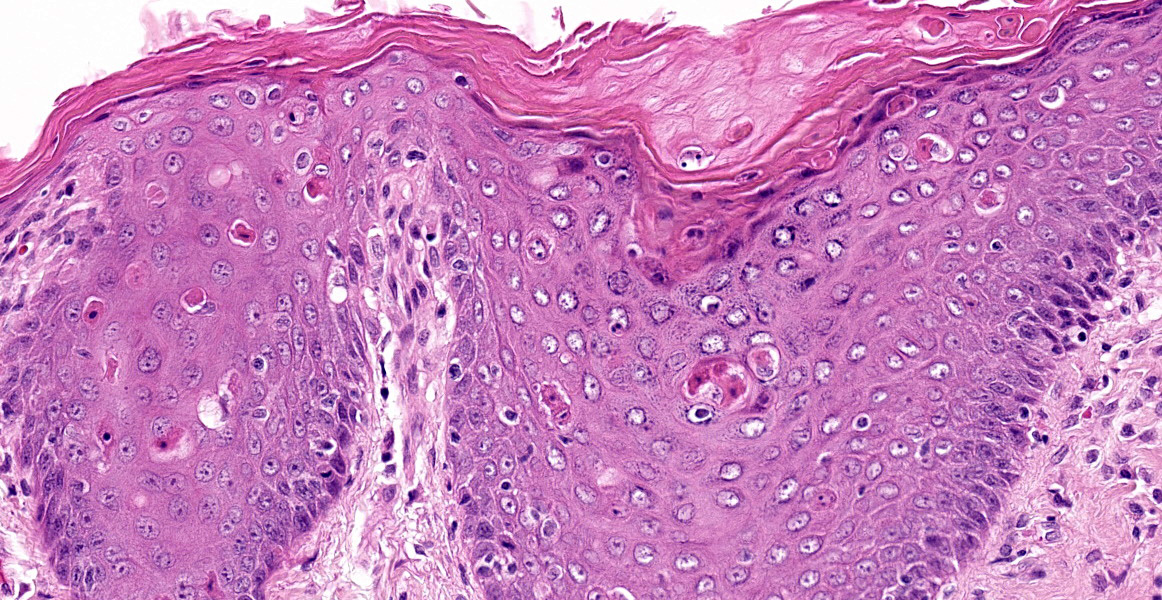

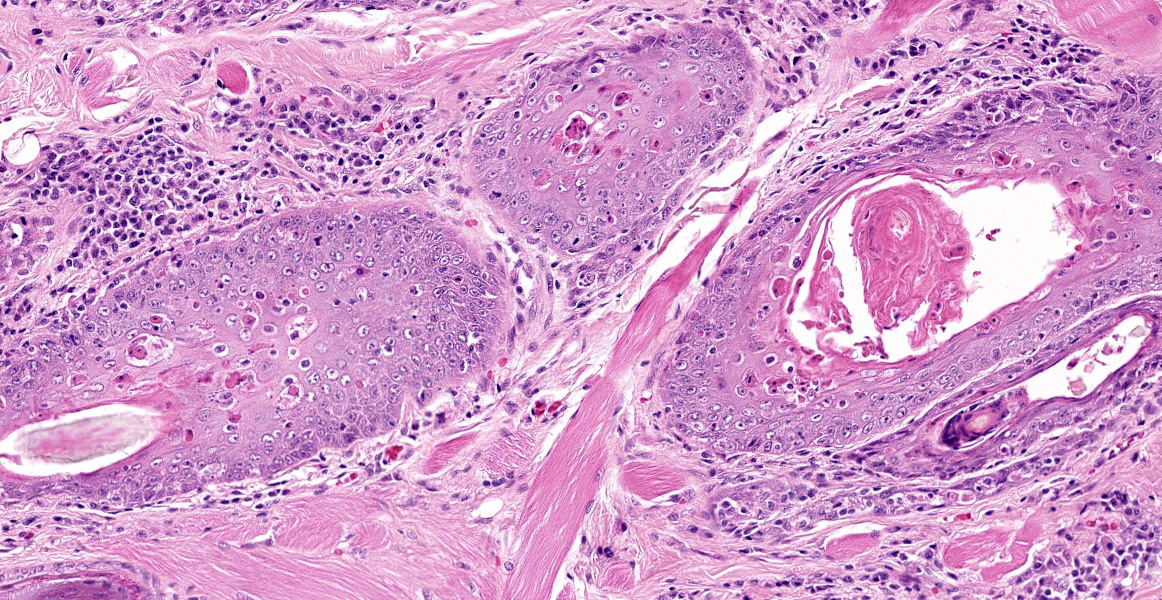

Individual spinous keratinocytes and basal cells are hypereosinophilic with pyknotic nuclei (cell death) and in some locations there are individual lymphocytes present within the epidermis adjacent to necrotic basal epithelial cells. The epidermis is variably acanthotic (up to 8 cells thick). There is marked, dense compact to basket weave orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis. Occasional nuclei are retained in the some of these keratin layers (parakeratosis). In some sections, there are occasional areas of erosion and thinning of the epidermis with rare areas of complete ulceration extending into the deeper dermis with exposure of the follicular epithelium. These ulcerated areas are covered by an up to 0.7 mm thick serocellular crust with degenerate neutrophils and keratin squames with admixed bacteria.

Lymphocytes are also present within the follicular epithelium (mural folliculitis) and follicules are decreased in size and number and are variably spaced (atrophy/loss). No sebaceous glands are visible in any section.

The superficial dermis has a band of lymphocytes with fewer plasma cells and there is edema of the superficial dermis.

PAS stain: There are rare intracorneal vesicles which contain a pale eosinophilic proteinaceous fluid. No fungal or parasitic organisms are seen in section.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Generalized transepidermal cytotoxic/interface dermatitis, with marked single cell death of epidermis and infundibulum of hair follicles, cell poor lymphocytic dermatitis and mural folliculitis, generalized follicular atrophy, absence of sebaceous glands and marked compact orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis.

Contributor’s Comment:

Cytotoxic / interface dermatitis is one of the eight inflammatory reaction patterns in veterinary dermatopathology. It features death of keratinocytes in the epidermis. There are two main subtypes – basal cytotoxic / interface dermatitis (skin manifestation of systemic lupus erythematosus and cutaneous lupus erythematosus) and transepidermal cytoxic / interface dermatitis where all layers are potentially involved – the stratum basale, spinosum and or stratum granulosum. It is called cytotoxic because of death of keratinocytes and the interface terminology is when there is a band of lymphocytes and or plasma cells in the superficial dermis. The primary target of the cytotoxic / interface process is the keratinocyte. The various diseases and syndromes that have the panepidermal or transepidermal pattern of keratinocyte death are either ulcerative or hyperkeratotic. They are ulcerative when the cell death is rapid and severe, and hyperkeratotic (parakeratotic) when the number of dead cells is low.

Transepidermal cytotoxic / interface dermatitis in humans is seen in the syndromes and diseases Stevens-Johnson syndrome, erythema multiforme, and toxic epidermal necrolysis.9

In veterinary medicine, separation of different diseases and syndromes is based on clinical findings including extent of the lesions, location, and progression. Because the lesions are similar on histology, diagnosis of individual diseases should be done by clinicians (including dermatologists). Pathologists recognize the reaction pattern.

This pattern of disease is considered immune-mediated. The trigger is not always identified. In animals, toxic epidermal necrolysis is more likely to be an adverse reaction to a drug; the death of cells is confluent.9

This rabbit has a clinically severe scaling or exfoliative dermatitis. The histologic pattern is a transepidermal cytotoxic pattern. The transepidermal pattern is well known in dogs where there are a variety of causes and disease syndromes.9 This is rare in rabbits, who have a disease profile much like cats. In cats, the diseases are divided into thymoma-associated7 and non-thymoma-associated exfoliative dermatitis.4

The mass in the cranial mediastinum of this rabbit was composed of a mixed population of neoplastic epithelial cells and normal small lymphocytes, thus it was a thymoma. In combination with the scaling dermatitis, the clinical presentation suggests paraneoplastic skin disease that is reported in thymoma in rabbits.2,6 Overall, studies on exfoliative dermatitis in multiple species both as a paraneoplastic and idiopathic condition provided strong evidence that this is an immune mediated process. There is accumulating evidence that this condition is driven by autoreactive cytotoxic T-cells.

Contributing Institution:

Department of Pathobiology, Ontario Veterinary College, University of Guelph, Guelph Ontario, Canada

JPC Diagnosis:

Mucocutaneous junction, lip: Keratinocyte apoptosis, multifocal, moderate, with lymphocytic satellitosis and marked hyperkeratosis.

JPC Comment:

This is the second example of an integumentary paraneoplastic syndrome reviewed this conference year. Case 2 of conference 4 featured paraneoplastic alopecia in a cat due to a carcinoma in the liver, and the contributor and conference comments provide a general review of paraneoplastic skin lesions in veterinary species. In addition to exfoliative dermatitis, thymomas have also been associated with other paraneoplastic syndromes such as myasthenia gravis, polymyositis, and granulocytopenia.1 Additionally, in dogs, thymomas may induce T-cell lymphocytosis, basophilia, or hypercalcemia of malignancy.8 Exfoliative dermatitis has also recently been reported in a goat with a thymoma.1

Thymomas arise from the thymic epithelium and contain variable amounts of lymphocytes. A World Health Organization classification scheme places thymomas in two broad categories based on the histologic appearance of the epithelium. Type B thymomas, the most common type in dogs, have neoplastic cells which are epithelioid in appearance and are further subtyped based on the density of lymphocytes.5 Type A thymomas have neoplastic cells which are spindloid in shape and accompanied by few lymphocytes.5 In a study of domestic rabbits, out of 2,970 neoplasms, 48 were thymomas, and the most common subtype was type B1.5

In a separate study of thymomas in 13 rabbits, the average age at diagnosis was 6.1 years, and the most common clinical signs were dyspnea, exercise intolerance, and bilateral exophthalmos.3 These signs were attributed to the mass’s space occupying effect in the thorax, and exophthalmos is thought to arise from cranial vena cava syndrome due to decreased venous return to the heart. In some cases, the exophthalmos was transient or accompanied by third eyelid prolapse.3

Conference participants discussed two main differential diagnoses in this case: erythema multiforme and exfoliative dermatitis. Given the potentially identical histologic features of these two syndromes, participants could only confidently say exfoliative dermatitis once the clinical history was known. Participants also remarked on the lack of sebaceous glands, a common finding in thymoma-associated exfoliative dermatitis of cats.7

References:

- Byas AD, Applegate TJ, Stuart A, Byers S, Frank CB. Thymoma-associated exfoliative dermatitis in a goat: case report and brief literature review. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2019; 31(6):905-908.

- Florizoone K. Thymoma-associated exfoliative dermatitis in a rabbit. Vet Dermatol. 2005; 16: 281-284.

- Kunzel F, Hittmair K, Hassan J, et al. Thymomas in Rabbits: Clinical Evaluation, Diagnosis, and Treatment. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2012; 48(2): 97-104.

- Linek M, Rüfenacht S, Brachelente C, von Tscharner C, Favrot C, Wilhelm S, Nett C, Mueller RS, Mayer U, Welle M. Nonthymoma-associated exfoliative dermatitis in 18 cats. Vet Dermatol. 2015; 26: 40-45.

- Robson HR, Yanez RA, Magestro LM, French SJ, Kiupel M. Type A thymoma in a pet rabbit. J Vet Diagn Ivest. 2022; 34(2): 327-330.

- Rostaher Prélaud A, Jassies-van der Lee A, Mueller RS, van Zeeland YR, Bettenay S, Majzoub M, Zenker I, Hein J. Presumptive paraneoplastic exfoliative dermatitis in four domestic rabbits. Vet Rec. 2013; 172: 155.

- Rottenberg S, von Tscharner C, Roosje PJ. Thymoma-associated exfoliative dermatitis in cats. Vet Pathol. 2004; 41: 429-433.

- Wikander YM, Knights K, Coffee C, et al. CD4 and CD8 double-negative immunophenotype of thymoma-associated lymphocytes in a dog. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2020; 32(6):918-922.

- Yager JA. Erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis: a comparative review. Vet Dermatol. 2014; 25: 406-e64.