Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2018-2019

Conference 17

30 January, 2019

CASE I: S1501813 (JPC 4084248).

Signalment: Six-year-old, intact male German shepherd dog (Canis familiaris)

History: This animal was born in the East coast of the US and then moved to the West coast, close to the border with Mexico. Up to date with vaccination. Presented to the clinic with signs of lethargy, anorexia and swelling of the right thoracic limb. Treated with antibiotics (Rilexine/cephalexine). The dog showed improvement, but a few days later developed diarrhea and neurological signs. On clinical examination, the dog evidenced disorientation, ataxia, nystagmus, generalized lymphadenomegaly, edema of the limbs and scrotum and peripheral neuropathy. The animal was treated with doxycycline and enrofloxacin intravenously, but died a few hours later.

Gross Pathology: The carcass was in good body condition. The subcutis of the distal limbs displayed small amounts of edema. The prescapular, popliteal and submandibular lymph nodes were mildly enlarged and fleshy. Lungs were diffusely red and wet, and the heart appeared rounded due to marked dilation of the right ventricle. The spleen was markedly enlarged with dark red fleshy parenchyma. Mesenteric lymph nodes were minimally enlarged.

Laboratory results: The blood chemistry (Table 1) revealed hypoalbuminemia without alteration of the A/G ratio. Alkaline phosphatase was mildly elevated and hypocalcemia was detected. The CBC (table 2) revealed leukocytosis due to neutrophilia and monocytosis, plus thrombocytopenia. The canine tick borne PCR panel (Table 3) was positive for Rickettsia rickettsii.

Table 1: Blood chemistry:

|

Test |

Result |

Ref range |

Units |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Total protein |

5.1 |

5.0-7.4 |

g/dL |

|

Albumin |

2.1 (LOW) |

2.7-4.4 |

g/dL |

|

Globulin |

3.0 |

1.6-3.6 |

g/dL |

|

A/G ratio |

0.7 (LOW) |

0.8-2.0 |

|

|

AST |

58 |

15-66 |

IU/L |

|

ALT |

38 |

12-118 |

IU/L |

|

Alk Phosphatase |

210 (HIGH) |

5-131 |

IU/L |

|

GGT |

5 |

1-12 |

IU/L |

|

Total bilirubin |

0.3 |

0.1-0.3 |

mg/dl |

|

BUN |

15 |

6-31 |

mg/dl |

|

Creatinine |

0.6 |

0.5-1.6 |

mg/dl |

|

BUN/Creatinine ratio |

25 |

4-27 |

|

|

Phsphorus |

4.7 |

2.5-6.0 |

mg/dl |

|

Glucose |

96 |

70-138 |

mg/dl |

|

Calcium |

8.5 (LOW) |

8.9-11.4 |

mg/dl |

|

Corrected calcium |

9.9 |

|

|

|

Magnesium |

1.5 |

1.5-2.5 |

mEq/L |

|

Sodium |

141 |

139-154 |

mEq/L |

|

Potassium |

4.2 |

3.6-5.5 |

mEq/L |

|

NA/K ratio |

34 |

27-38 |

|

|

Chloride |

111 |

102-120 |

mEq/L |

|

Cholesterol |

277 |

92-324 |

mg/dl |

|

Trygliceride |

88 |

29-291 |

mg/dl |

|

Amylase |

723 |

290-1125 |

IU/L |

|

Lipase |

65 (LOW) |

77-695 |

IU/L |

|

CPK |

107 |

59-895 |

IU/L |

Table 2: CBC:

|

Test |

Result |

Ref range |

Units |

|---|---|---|---|

|

WBC |

15.6 (HIGH) |

4.0-15.5 |

103/uL |

|

RBC |

5.5 |

4.8-9.3 |

106/uL |

|

HGB |

12.5 |

12.1-20.3 |

g/dL |

|

HCT |

38 |

36-60 |

% |

|

MCV |

69 |

58-79 |

fL |

|

MCH |

22.7 |

19-28 |

pg |

|

MCHC |

33 |

30-38 |

g/dL |

|

Blood parasites |

None seen |

|

|

|

RBC morphology |

Normal |

|

|

|

Platelet count |

75 (LOW) |

170-400 |

103/uL |

|

Platelet Est |

Adequate |

|

|

|

Neutrophils (HIGH) |

13260 |

2060-10600 |

/uL |

|

Bands |

0 |

|

|

|

Lymphocytes |

1248 |

690-4500 |

/uL |

|

Monocytes (HIGH) |

1092 |

0-840 |

/uL |

|

Eosinophils |

0 |

0-1200 |

/uL |

|

Basophils |

0 |

0-150 |

/uL |

Table 3. Canine tick borne PCR panel profile:

|

Anaplasma phagocytophylum |

Negative |

|

Anaplasma platys |

Negative |

|

Babesia canis |

Negative |

|

Babesia spp (non-canis) |

Negative |

|

Bartinella henselae |

Negative |

|

Bartonella vinsonii |

Negative |

|

Ehrlichia canis |

Negative |

|

M haemocanis/hematoparvum |

Negative |

|

Neorickettsia risticii |

Negative |

|

Rickettsia rickettsii |

Positive |

Microscopic Description:

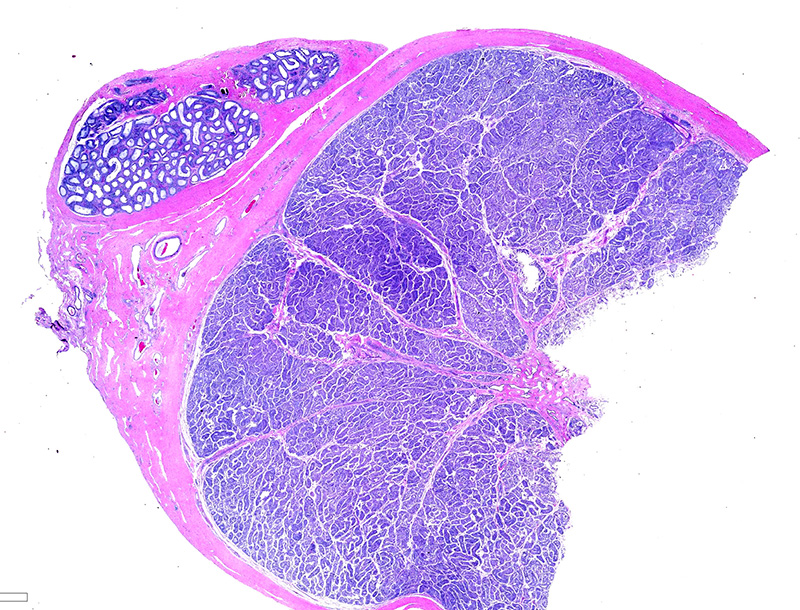

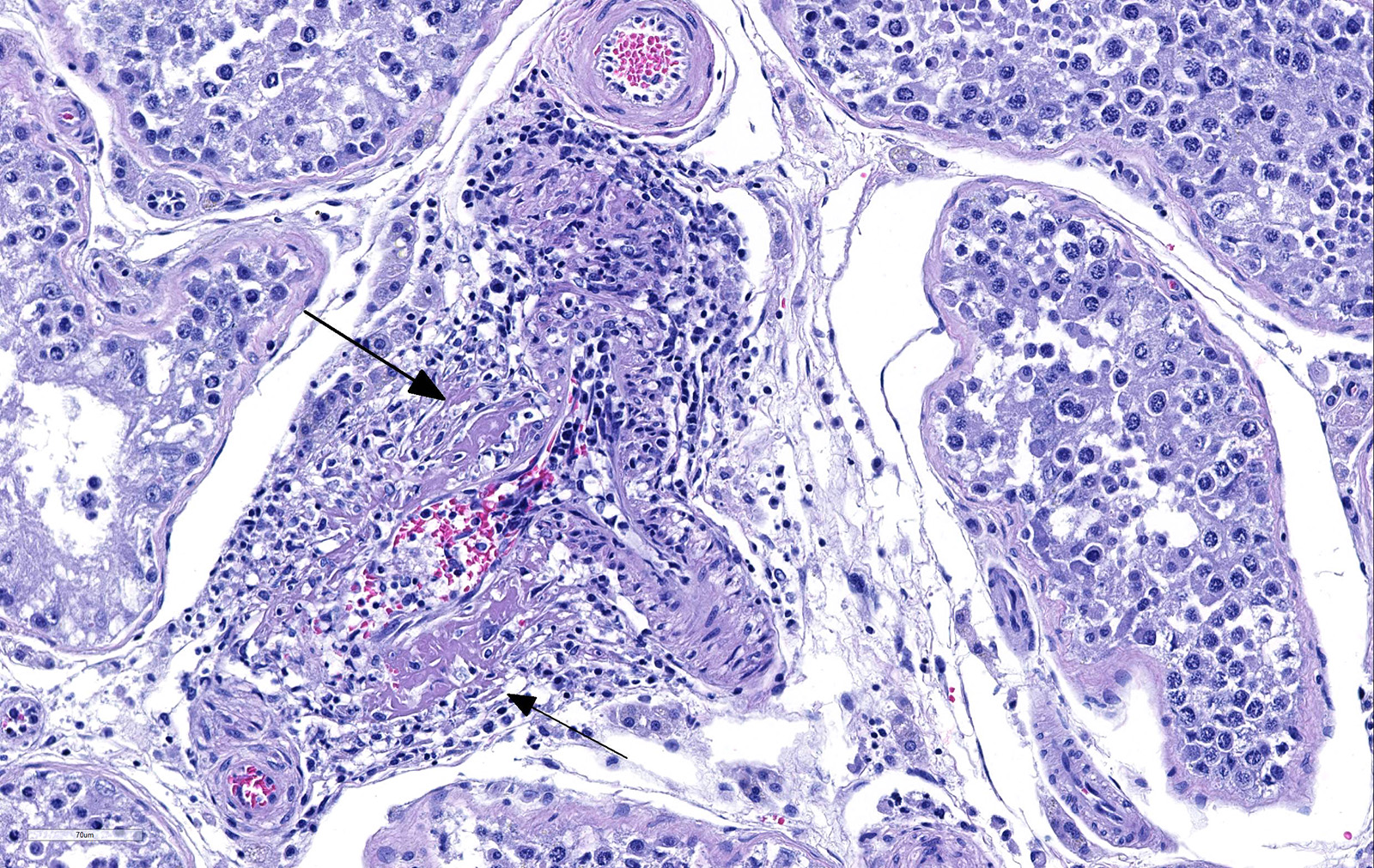

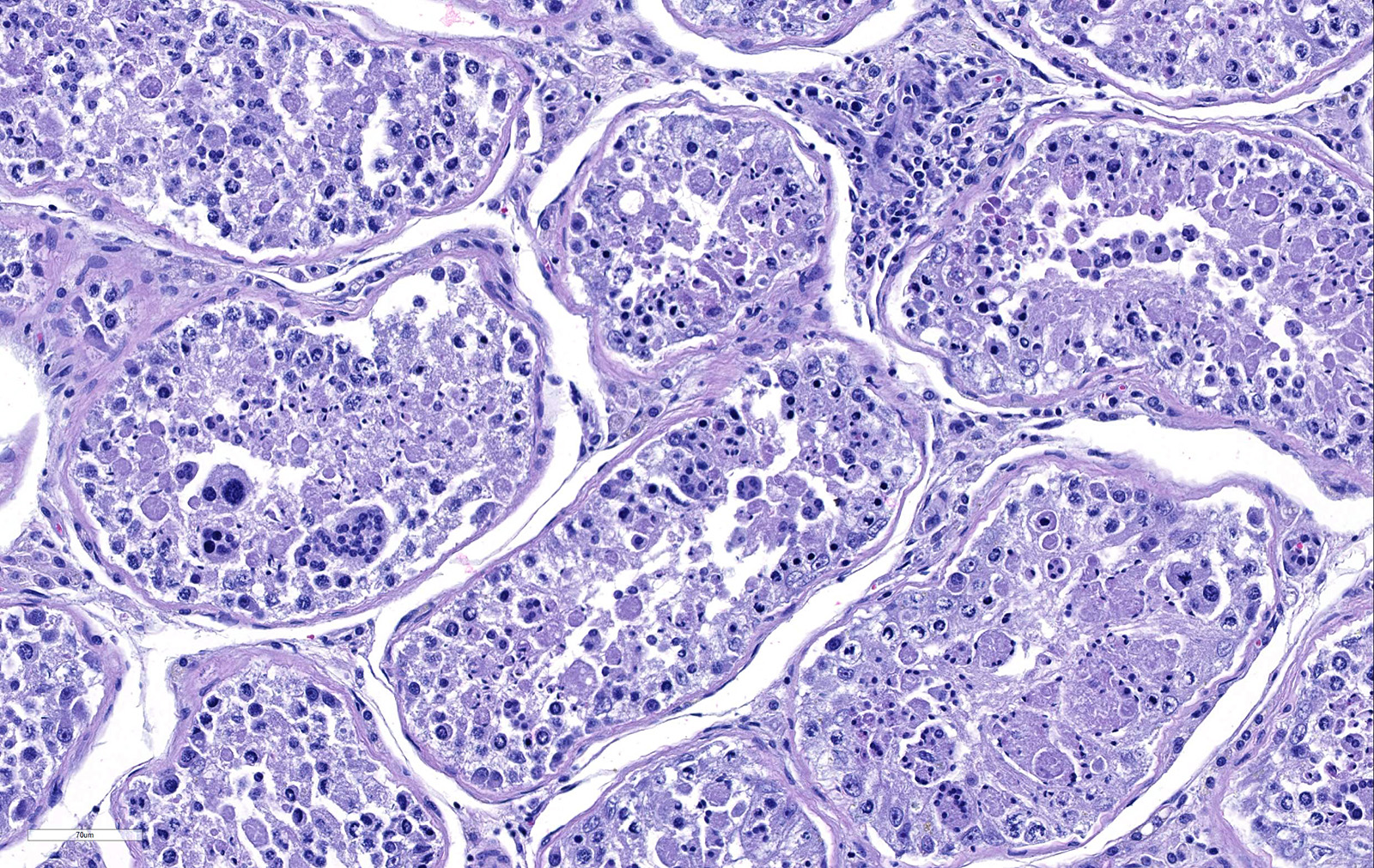

Testicle: Section include testicle and tunica albuginea, head of epididymis and vascular plexus. Scattered throughout the section, numerous vessels display segmental inflammatory changes, characterized by fibrinoid degeneration of the vascular media and transmural inflammatory infiltrates, composed mostly of lymphocytes, plasma cells and macrophages. Endothelial cells are plump and frequently detached. In addition to the inflammatory component, necrotic cellular debris are identified within the media and adventitia of the affected vessels. Occasionally, the adventitia is also expanded with fibrin. These findings were more prominent at the testicular vein (pampiniform venous plexus), but could be found in any medium and small caliber vessel. Other findings within the testicle is segmental tubular degeneration, characterized by the presence of multinucleated cells in the lumen of seminiferous tubules.

Similar vascular findings with varying degrees of severity were also identified (but not included in the section) in: brain, subcutis of distal limbs, eye, lung, heart, skeletal muscle, tongue and gastrointestinal wall. Other significant histological findings included meningoencephalitis, mild hepatitis and dermatitis (the latter presumably associated with tick bite site).

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Testicle:

- Vasculitis, lymphohistiocytic to necrotizing, marked, sub-acute, segmental.

- Testicular degeneration, mild, multifocal.

Contributor’s Comment: “Rocky Mountain Spotted fever” (RMSF) is a tick-transmitted zoonotic infectious disease caused by Rickettsia rickettsii. Of the tick-borne diseases in America, RMSF is the most severe, and can result in rapid course of disease and high mortality rate. This disease can be transmitted by ticks of the Dermacentor, Rhipicephalus and Amblyomma genera.7 In the USA, Dermacentor variabilis and Dermacentor andersoni are most commonly responsible for the transmission of the disease and they act as vectors, reservoirs and naturals hosts for R. rickettsii. In its natural cycle, R. rickettsii is maintained in persistently infected tick population and small rodent reservoir hosts. Interestingly, transovarial transmission from infected females to eggs and transmission between adult ticks during mating can maintain the infection in a population without additional infectious feedings.5

Once a dog is bitten by infected ticks, there is invasion of small vessels and replication, with damage of endothelial cells. Rickettsiae use phospholipase A proteases and free radicals to induce oxidative and peroxidative damage to the host cell membrane, which will finally result in cell death. In addition, cell mediated immunity induces apoptosis in cells infected with rickettsiae via mechanisms such as the CD8 T lymphocyte cytotoxicity.1 The net effect of these mechanisms is endothelial cell damage, which is followed by immune and phagocytic cellular responses plus platelet activation and activation of the coagulation and fibrinolytic systems, resulting in thrombosis.1,7 Platelet consumption is considered as the primary cause of thrombocytopenia in dogs. However, antiplatelet antibodies has also been identified in infected animals.3 Hypoalbuminemia is often observed and is probably caused by leakage associated with generalized vascular damage.2

Because RMSF lesions are characteristically associated with vasculitis throughout the body, it is not surprising that disease can manifest with a wide variety of clinical signs and can be mistaken for an undifferentiated viral illness during the first days of manifestation.1 Clinical signs includes fever (early manifestation), edema and hyperemia of the lips, penile sheath, scrotum (with abnormal gait), pinna and ventral abdomen. Petechial and ecchymotic hemorrhages may develop subsequent to the acute illness in mucous membranes, skin, pleura and gastric wall, in addition to hemorrhagic colitis and generalized lymphadenopathy.2,7 Histologically, the most prominent lesion in necrotizing vasculitis of small veins, capillaries and arterioles with perivascular accumulation of mononuclear cells. This lesion is frequently seen in the skin, testicle, alimentary tract, pancreas, kidney, urinary bladder, myocardium, retina and skeletal muscle. In addition, acute meningoencephalitis, interstitial pneumonia and necrosis of the myocardium, adrenal gland and liver can be present.7

Among the differential diagnosis for vasculitis in dogs, other causes of secondary vasculitis should be considered, such as autoimmune diseases (such as lupus erythematosus), infections with canine circovirus, Leishmania spp, Angiostrongylus vasorum and Dirofilaria immitis, and exposure to therapeutic products, such as carprofen and meloxicam.4,9

Contributing Institution:

California Animal Health and Food Safety Laboratory

San Bernardino Branch

105 W Central Ave

San Bernardino, CA 92408

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Testis, arterioles: Vasculitis, necrotizing, random, multifocal, severe, with seminiferous tubule necrosis.

2. Testis, seminiferous tubules: Degeneration and atrophy, diffuse, moderate, with spermatid giant cell formation.

JPC Comment: The contributor has provided an excellent discussion of Rocky Mountain spotted fever in the dog. Humans and dogs are the only two species in which clinical disease (and life threatening infections) may result from Rickettsia rickettsiae infection. While a number of small mammals, including rodents, rabbits, and opossums may provide a reservoir for the bacterium, clinical disease has not been documented in these species. Recent inoculation studies in horses failed to elicit clinical disease.

Clinical symptoms of RMSF in humans arise abruptly and generally include high fever, headache, nausea, vomiting, and generalized myalgia. A generalized macular rash appears two to four days later which may or may not be accompanied by eschar at the site of the tick bite, and often starts on the wrists, ankles, and forearms. In 50-60% of patients, the lesions evolved into petechiae or purpura. More severe lesions include gangrene, pulmonary and cerebral edema, myocarditis, renal failure and disseminated intravascular coagulation. 5-10% of patients will die despite treatment.6

The contributor refers to “secondary vasculitis”. This particular nomenclature comes from human medicine. The term “primary” vasculitis refers to blood vessel wall injury arising without an apparent cause, and “secondary” vasculitis in which an apparent cause (infectious, immune-mediated, or neoplastic) is identified. Few well-defined syndromes of primary vasculitis exist in veterinary medicine, to include the so-called “beagle pain syndrome”, as well as a number cutaneous vasculitides in the dog. The vasculitis seen in this case, secondary to R. rickettsii infection, would be classified as “secondary” vasculitis. A retrospective study of 42 cases by Swann et al in 2015, compared cases of vasculitis which fell into both categories. Significant differences between the two groups were not many, with female dogs more likely to develop primary vasculitis, and dogs with primary vasculitis were more likely to have elevated serum globulin concentrations. The authors concluded that there does not appear to be well-defined syndromes of primary and secondary vasculitis in the dog as there are in humans.9

In veterinary medicine, the determination of “small” vs. “medium” arterioles is not well defined, due to the range of species we often examine (i.e., in a gerbil, all arteries are small). In human medicine, the definition is much more well defined, with luminal measurements defining “large”,

”medium”, and “small”. The moderator suggested that in any animal species, the aorta and the pulmonary artery are should be considered large, direct branches off of them would be “medium” and a third or more distal branches represent “small” arteries.

References:

- Chen LF, Sexton DK. What’s new in Rocky Mountain spotted fever? Infect Dis Clin N Am 2008; 22 (3): 415-432.

- Greene CE, Kidd L, Breitschwerdt Rocky Mountain and Mediterranean spotted fevers, and typhus. In: Greene CE, ed. Infectious diseases of the dog and cat. 4th ed. St Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2012: 259-276.

- Grindem CB, Breitschwerdt EB, Perkins PC, Culins LD, Thomas TJ, Hegarty BC. Platelet-associated immunoglobulin (antiplatelet antibody) in canine Rocky Mountain spotted fever and Ehrlichiosis. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1999; 35 (1): 56-61.

- Li L, McGraw S, Zhu K, Leuttenegger CM, Marks SL et al. Circovirus in tissues of dogs with vasculitis and hemorrhage. Emerg Infect Dis 2013; 19 (4): 534-541.

- Nicholson WL, Allen KE, McQuiston JH, Breitschwerdt EB, Little SE. The increasing recognition of rickettsial pathogens in dogs and people. Trends Parasitol 2010; 26 (4): 205-2012.

- Parola P, Paddock DC, Socolovschi C, Labruna MG, Mediannikov O, Kernif T, Abdad MY, Stenos J, Bitam I, Fournier P, Raoult. Update on tick-borne rickettsioses around the world: a geographic approach. Clin Microbiol Rev 2013; 26(4):657-702

- Robinson WF, Robinson NA. Cardiovascular system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer’s Pathology of domestic animals. 6th ed Vol 3. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2015: 1-101.

- Shaw SE, Day MJ, Birtles RJ, Breitschwerdt EB. Tick borne infectious diseases of dogs. Trends Parasitol 2001; 17 (1): 74-80.

- Swann JW, Priestnall SL, Dawson C, Chang YM, Garden OA. Histologic and clinical features of primary and secondary vasculitis: A retrospective study of 42 dogs (2004-2011). J Vet Diagn Invest 2015; 27 (4): 489-496.

- Ueno TE, Costa FB, Moraes-Filho J, Agostinho WC, Fernandes WR, Labruna MB. Experimental infection of horses with Rickettsia rickettsii. Parasit Vectors 2016; 9(1):499.