CASE 4: L16758 (4114759-00)

Signalment: 16-year-old, female, serval (Leptailurus serval)

History:

The animal was presented to the Baton Rouge zoo's veterinary hospital for recurrent hematuria, pollakiuria and intermittent anorexia. Interpretation of abdominal ultrasound revealed thickening of the urinary bladder wall (image capture was not available). Hematuria and pyuria were confirmed via free catch urinalysis, with hematuria refractory to antimicrobial therapy. Due to persistent anorexia resulting in significant weight loss and an overall loss in the quality of life the serval was humanely euthanized.

Gross Pathology:

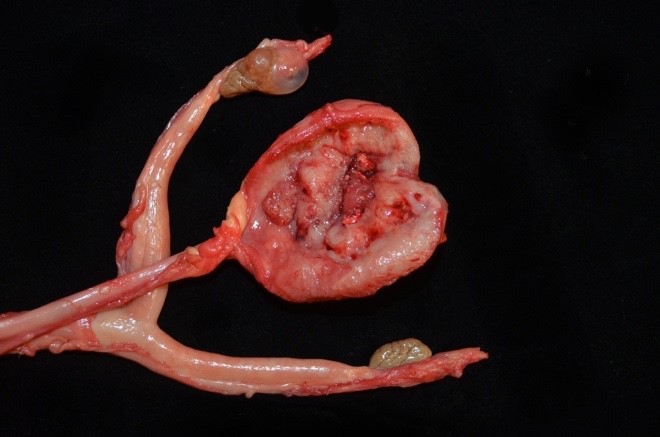

Approximately 80% of the urinary bladder body was transmurally expanded by a pale tan-to-red, multinodular, infiltrative, poorly demarcated neoplasm measuring 3.5 x 3.0 x 0.6cm. Abdominal adipose tissue was segmentally adhered to the ventral adventitial surface of the urinary bladder. The lumen of the urinary bladder was devoid of urine and no significant free fluid was observed in the peritoneal cavity. No evidence to support urinary obstruction (i.e. hydroureter and hydronephrosis) were observed. A yellow fluctuant paraovarian cyst measuring 1.2 cm in diameter was present along the cranial pole of the right ovary. Kidneys were interpreted as within normal limits grossly.

Laboratory results:

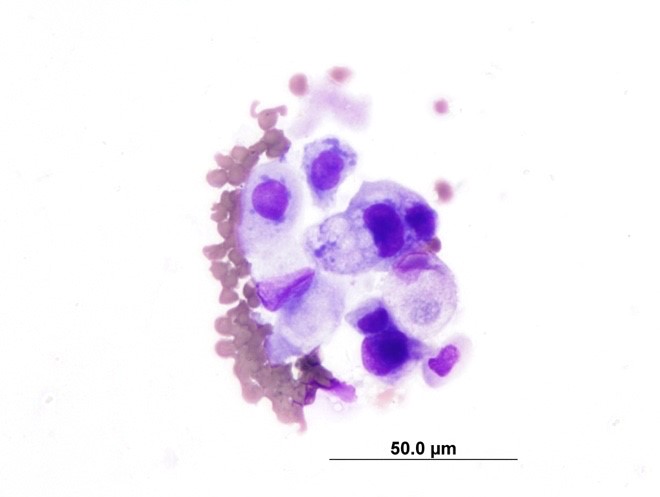

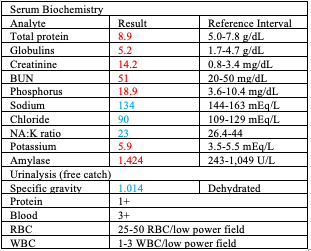

A cytospin preparation of urine sediment (free catch) revealed 1-3 epithelial cells per high power field, some of which displayed moderate atypia including increased cytoplasmic basophilia, variable and increased nucleus:cytoplasm ratio, anisokaryosis, rare multinucleation, and prominent nucleoli. Serum biochemistry findings included hyperproteinemia with hyperglobulinemia, marginal azotemia, hyperphosphatemia, hyponatremia, hypochloremia, decreased NA:K ratio,

hyperkalemia, and hyperamylasemia. Significant urinalysis findings included inappropriately concentrated urine in the face of a clinically dehydrated animal, proteinuria, hematuria, and pyuria.

Microscopic description:

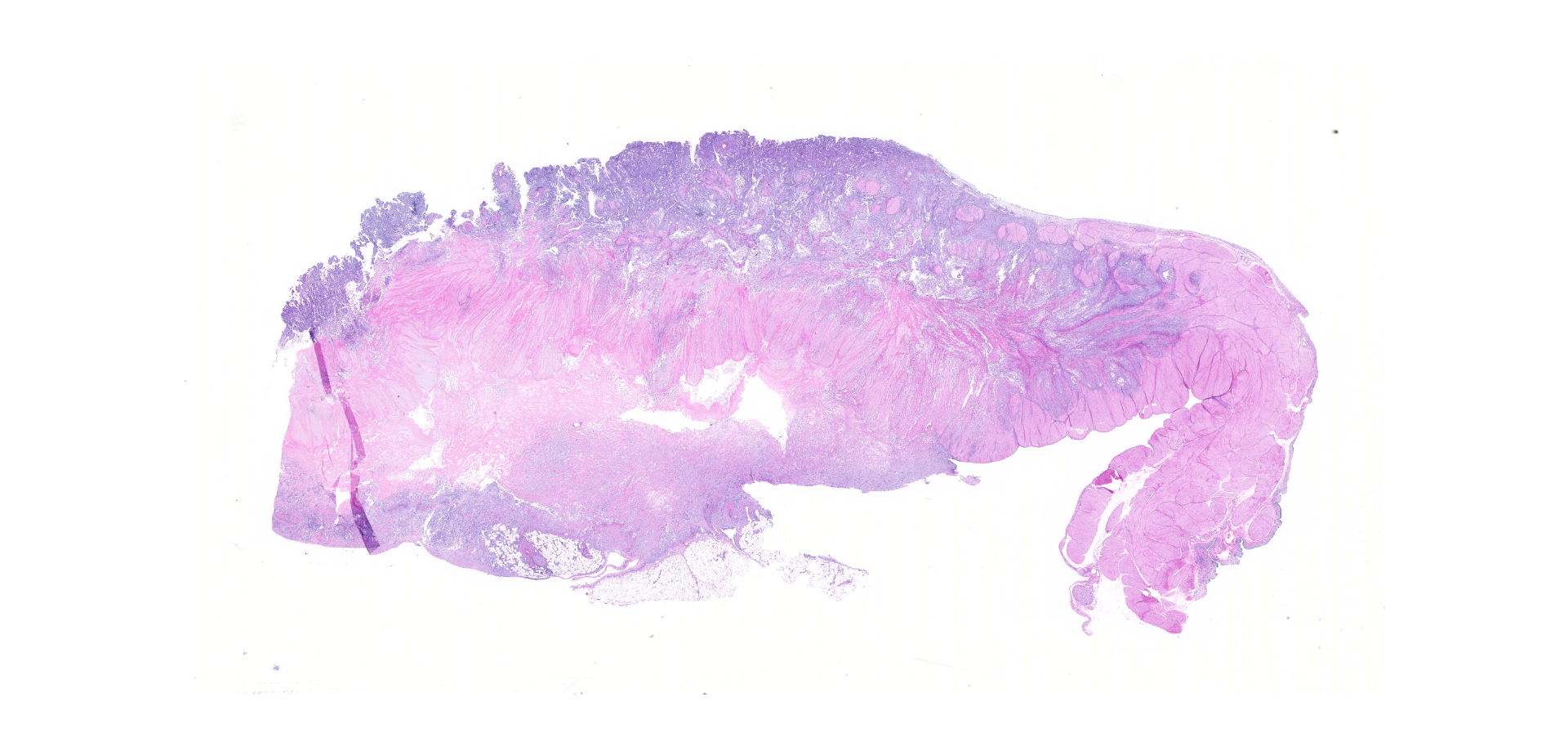

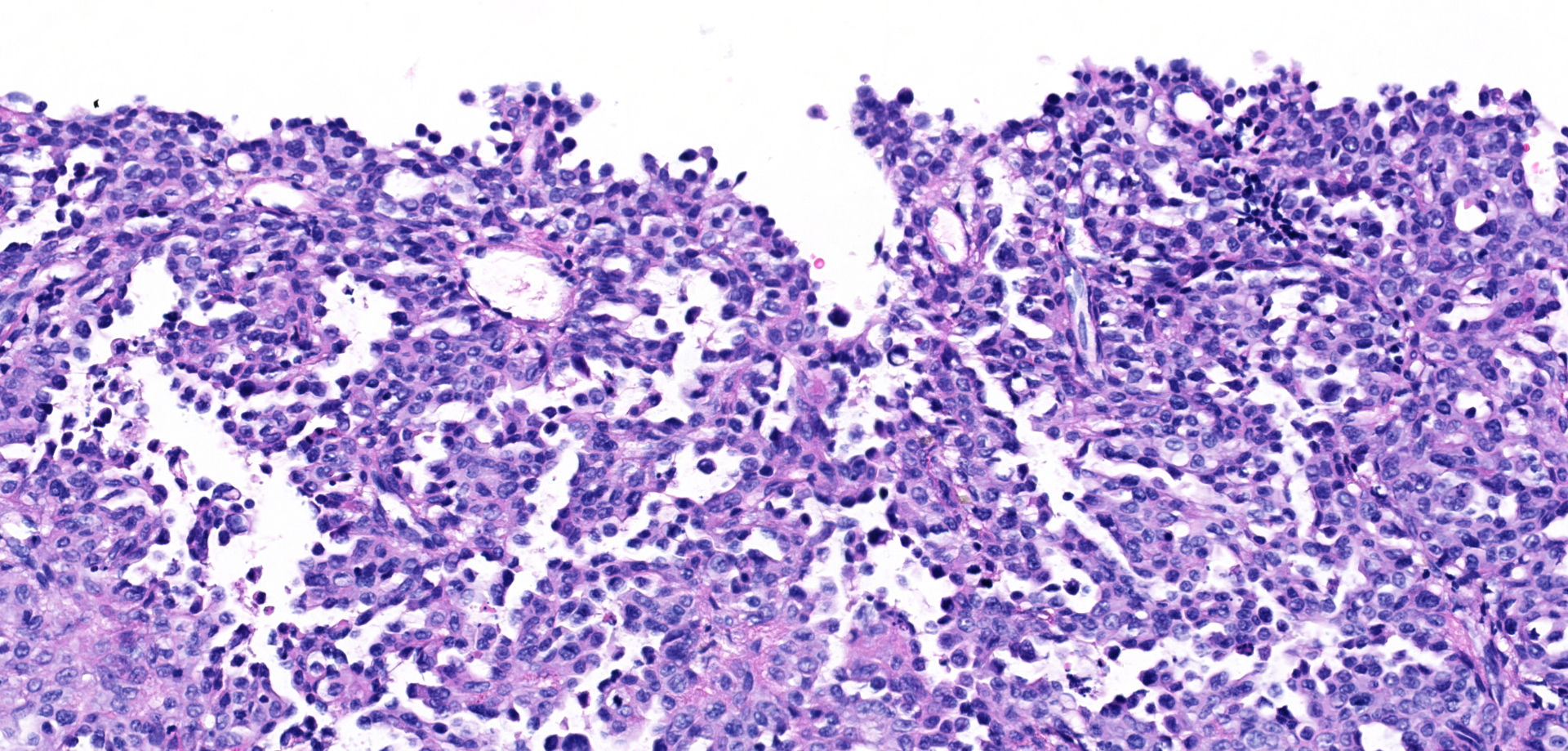

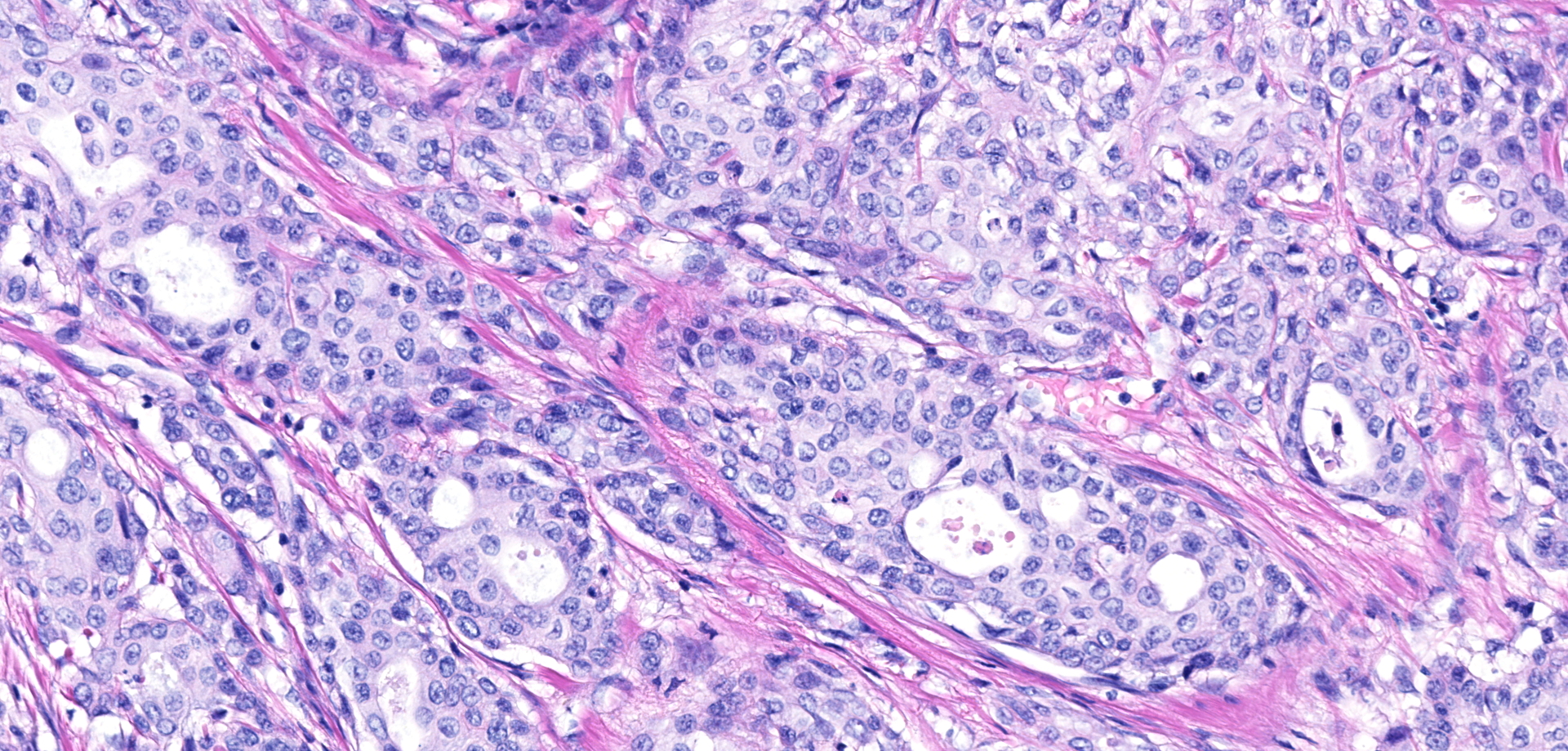

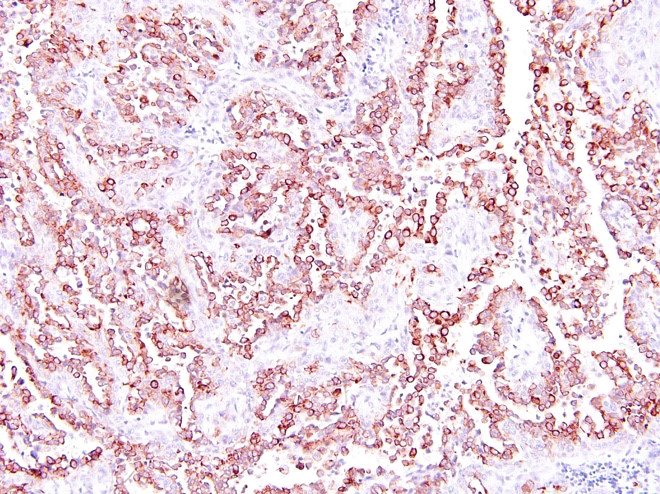

Urinary bladder neoplasm: Arising from transitional urothelium, infiltrating the propria-submucosa and muscularis, with extension into the adventitia and adjacent peritoneal adipose tissue is a raised, non-papillary, infiltrative, unencapsulated, moderately-to-densely cellular neoplasm. Neoplastic cells are composed of cuboidal-to-columnar epithelial cells arranged in acini, tubules, and trabeculae, which are supported by a moderate-to-dense fibrovascular stroma (desmoplasic/scirrhous response). Neoplastic cells have variably distinct cellular borders, a moderate amount of granular eosinophilic cytoplasm, round to oval nuclei with finely stippled chromatin, and 1-2 prominent centrally located magenta nucleoli. Anisocytosis and anisokaryosis are moderate, with 20 mitotic figures per 10 high powered fields. Neoplastic cells display strong cytoplasmic chromogenic immunoreactivity to cytokeratin AE1/AE3, with loss of cytokeratin 7 immunoreactivity when compared to neighboring surface transitional epithelium. Uroplakin III and cytokeratin 20 antibodies were not available for evaluation. Large areas of mural necrosis are represented by lakes of amorphous hypereosinophilic cellular debris and are commonly admixed with foci of basophilic mineralization (dystrophic). Vascular invasion was not observed in the sections examined; however, multiple microscopic foci of pulmonary metastasis were observed expanding alveolar septa.

Kidney (not depicted in submitted slide): The interstitium is expanded multifocally by mild fibrosis associated mild tubular degeneration and atrophy. Some tubules contain large clear spaces within the lumina (lipid casts). Lymphoplasmacytic and histiocytic inflammation surrounds these foci. Some tubules have ruptured resulting in the release of intraluminal lipid content into adjacent interstitium, associated with accumulation of lipid laden macrophages (lipogranulomatous inflammation).

Contributor's morphologic diagnosis:

Urinary bladder: Urothelial carcinoma, non-papillary, infiltrative, with pulmonary micrometastasis (not evident in submitted slide)

Kidneys: Nephritis, tubulointerstitial, lipogranulomatous, with interstitial fibrosis, lipid casts, tubular degeneration and atrophy, mild, chronic

Contributor's comment:

Urothelial carcinomas of the urinary bladder are classified as papillary or non-papillary and as infiltrating or non-infiltrating. Papillary tumors project into the lumen of the urinary bladder, while non-papillary tumors often are either flat or fail to form a discrete exophytic mass. Infiltrating tumors are characterized by extension into the underlying substantia propria and muscularis, with occasional transmural involvement; meanwhile non-infiltrating tumors do not invade the substantia propria. Non-papillary infiltrative tumors are most likely to metastasize, followed by papillary infiltrative tumors. Metastasis is not likely with papillary non-infiltrative tumors. Non-papillary non-infiltrative tumors are synonymous with carcinomas in situ and are confined to the surface epithelium. Histologic features that may suggest an increased likelihood of metastasis include marked cellular atypia, prominent muscular invasion and/or desmoplastic response, and the presence of vascular invasion.4 Metastasis is most commonly reported to regional lymph nodes, lungs, and bones, but peritoneal and cutaneous implantation have been documented.

Urothelial carcinoma represents the most common urinary bladder neoplasm of both cats and dogs with similar reported frequencies. In dogs, females are overrepresented with up to a 2:1 ratio reported in multiple studies.7 Additionally, neutered dogs, independent of sex, are more commonly affected than intact dogs.6 In cats, this predilection for neutered animals has not been consistently observed and one study identified male cats to be at an increased risk when compared to female cats. Several breed dispositions have been identified, including Scottish Terriers, Airedales, Shetland Sheepdogs, Beagles, Collies, Wire Hair Fox Terriers, and West Highland White Terriers4,6, meanwhile no breed predilection has been identified in domestic cats. Risk factors for development of urinary bladder urothelial carcinoma are best described in dogs, which include exposure to topical insecticides, obesity, and administration of cyclophosphamide; meanwhile second hand smoke has not been proven to represent a risk factor as is reported in humans.2,6 In cattle, spontaneous tumor development of the urinary bladder is uncommon; however, up to 25% of animals known to graze pasture rich in bracken fern have been reported to develop urinary bladder tumors including urothelial carcinoma.8 Bracken fern contains ptaquiloside, a known carcinogen, which is believed to act synergistically with Bovine papillomavirus type-2 (BPV-2) to cause neoplastic transformation.

Initially this animal was presumed to be suffering from chronic recurrent bacterial cystitis, as hematuria was initially responsive to antimicrobial treatment. Hematuria ultimately became refractory to treatment and ancillary diagnostics were pursued (i.e. ultrasound and urine sediment interpretation). Interpretation of these diagnostics placed urothelial carcinoma as the top differential. Serum biochemistry findings were in part attributed to the clinically appreciated dehydration, manifesting as pre-renal disease (i.e. azotemia, hyperphosphatemia). The immediate cause of the hyperkalemia, hyponatremia and hypochloremia were unknown, as the animal clinically had no history of vomiting or diarrhea in the face of dehydration. Although the collective electrolyte abnormalities (i.e. hyperkalemia, hyponatremia, and hypochloremia) were highly suggestive of urine and blood equilibration through the peritoneum (i.e. uroperitoneum), no appreciable free abdominal fluid was identified at the time of necropsy. If free fluid was present in the peritoneum at the time of necropsy, ascitic fluid levels of creatinine would have been expected to be markedly higher than those in the blood. In the absence of discrete abdominal fluid and an alternative explanation, we propose that adventitial plugging of the urinary bladder by adipose tissue resulted in a slow, controlled, and chronic release of urine into the abdomen that was able to equilibrate at a rate where accumulation of fluid was no appreciable at necropsy. Inadequate urine concentrating capacity in the face of dehydration (urine specific gravity of 1.014; expect ? 1.035 in a dehydrated feline) supports concomitant renal disease, which is believed to have played a contributory role in the electrolyte disturbances and azotemia observed in this case. Lipogranulomatous inflammation has been documented in domestic cats after various types of renal insults such as experimental ischemia reperfusion injury and nephrotoxicity. Tubular injury and tubulorhexis can lead to release of intraepithelial lipid into the interstitium, which incites a granulomatous inflammatory response. This inflammation can then perpetuate further renal injury by expansion of the interstitium and compression of the peritubular capillaries.9 Planet Earth, Season 2, Grasslands showcases the serval in its natural habitat.

Contributing Institution:

Boston University/NEIDL 620 Albany Street, Boston, MA, 02118

JPC diagnosis:

Urinary bladder: Urothelial (transitional) cell carcinoma, serval, feline.

JPC comment:

During conference discussion, it was noted that different sections had different predominant patterns, including features of non-papillary, infiltrative, or papillary, infiltrative.

While not all urothelial carcinomas share a common cause, approximately 80% of canine urothelial carcinomas are associated with mutation in the BRAF V595E allele. This allele in dogs is homologous to BRAF V600E mutation in humans, which is found in approximately 50% of human melanomas.10 Point of care tests are currently performed on voided urine, and one successful method is the digital droplet PCR test (ddPCR). Even though approximately 20% of canine cases of urothelial carcinoma do not possess the mutation, the ddPCR test has a sensitivity around 80%.5

While the BRAF mutation testing is not available for cats yet, additional work has been performed to characterize the expression of cyclo-oxygenase 1 (COX-1), cyclo-oxygenase 2 (COX-2), lipoxygenase 5 (LOX-5), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). A small study of feline urothelial carcinomas showed that most expressed COX-1 and COX-2, and that the neoplasms responded to the COX inhibitor meloxicam, with increased mean survival times.

LOX-5 over-expression has been linked to human neoplasia, including prostatic, renal, and bladder cancer. LOX-5 has a pro-inflammatory effect, activated by nF-KB, and leading to sustained angiogenesis through induction of VEGF, cell migration, invasion, and resistance to apoptosis by inhibition of caspase 3. An investigation into canine urothelial carcinomas showed that 95% of tumors expressed LOX-5. Additionally, canine urothelial carcinomas also express COX-2, which is generally not expressed in normal canine bladder urothelium.1

Increased receptor tyrosine kinase HER2 activity has been shown in a subset of human breast cancers, as is a recent target of interest for canine urothelial carcinomas. While increased HER2 expression correlates with a poorer prognosis, no correlations between HER2 expression and age, sex, sexual status, tumor size, tumor T stage, lymph node involvement, distant metastasis, or recurrence in canine urothelial carcinomas. However, there was increasing HER2 expression across groups, from polypoid cystitis, to grade 1 carcinoma, to grade 2 carcinoma. Grade 3 urothelial carcinomas had decreased HER2 expression than in grades 1 and 2, which may represent dedifferentiation of neoplastic cells and may be analogous to the loss of uroplakin III expression in grade 3 urothelial carcinomas.11

The UPII-SV40T strain of transgenic mice are a model for urothelial carcinoma, as they develop invasive urothelial tumors due to expression of Simian virus large T antigen (Tag). Most often, these tumors are classified as high grade, invasive carcinomas by 40 weeks of age. The chemopreventive, licofelone, is a dual COX-2 and LOX-5 inhibitor, which has been shown to prevent human colon, lung, and prostate cancers. Mice fed licofelone developed fewer invasive, and fewer high-grade urothelial carcinomas, and may represent a future treatment for other species.3

References:

1. Finotello R, Schiava L, Ressel L, Frohmader A, Silvestrini P, Verin R. Lippoxygenase-5 expression in canine urinary bladder: Normal urotherlium, cystitis and transitional cell carcinoma. J Comp Path. 2019;170:1-9.

2. Landolfi JA, Terio KA. Transitional cell carcinoma in fishing cats (Prionailurus viverrinus): Pathology and expression of cyclooxygenase-1, -2, and p53. Vet Pathol 2006;43:674-681.

3. Madka V, Mohammed A, Li Q, et al. Chemoprevention of urothelial cell carcinoma growth and invasion by the dual COX-LOX inhibitor licofelone in UPII-SV40T transgenic mice. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2014;7(7):708?716.

4. Meuten DJ. Tumors of the Urinary System. In: Meuten DJ. Tumors of Domestic Animals. 4th ed. Ames: Iowa State Press. 2002; 529-535.

5. Mochizuki H, Shapiro SG, Breen M. Detection of BRAF mutation in urine DNA as a molecular diagnostic for canine urothelial and prostatic carcinoma. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(12):e0144170.

6. Mutsaers AJ, Widmer WR, Knapp DW. Canine transitional cell carcinoma. J Vet Intern Med 2003;17:136?144.

7. Norris AM, Laing EJ, Valli VEO, et al. Canine bladder and urethral tumors: a retrospective study of 115 cases (1980-1985). J Vet Intern Med 1992;6:145-153.

8. Pamukcu AM, Price JM, Bryan GT. Naturally occurring and braken-fern-induced bovine urinary bladder tumors. Clinical and morphological characteristics. Vet Pathol 1976;13(2):110-22

9. Schmiedt CW, Brainard BM, Hinson W, et al. Unilateral renal ischemia as a model of acute kidney injury and renal fibrosis in cats. Vet Pathol 2016;53:87-101.

10. Tagawa M, Tambo N, Maezawa M, et al. Quantitative analysis of the BRAF V595E mutation in plasma cell-free DNA from dogs with urothelial carcinoma. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(4):e0232365.

11. Tsuboi M, Sakai K, Maeda S. Assessment of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 expression in canine urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Veterinary Pathology. 2019;56(3):369-376.