Signalment:

Gross Description:

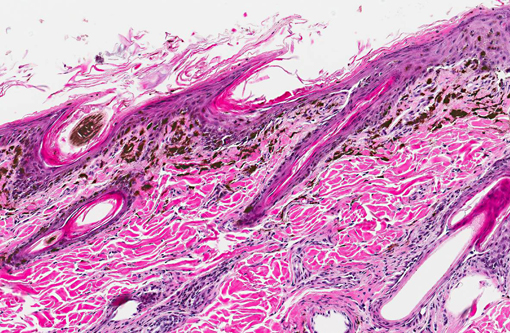

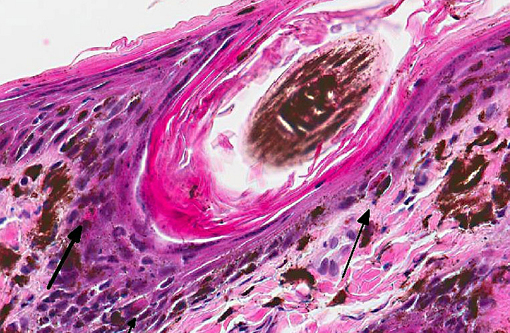

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

This disease was first reported in 1992 under the name of Hereditary lupoid dermatosis of the German Shorthaired Pointer.(3) In a relatively recent study, 17 patients were evaluated. The lesion distribution among the sexes was approximately 2:1 (female:male).(1) Young dogs were affected with a mean of 10 months of age (1.8-48 months). Prominent clinical findings in the study were initially scaling (100%), alopecia (76%), crusting with or without ulceration (52%), generalized lymphadenopathy (32%), follicular casts (28%), mild pruritus (28%), and intermittent pyrexia (12%). Lesion distribution early in the course of the disease was reported at the muzzle, pinnae, and the dorsal trunk. The distribution progressed to the limbs and ventral trunk with 52% of the dogs displaying generalized disease.

Clinical pathologic changes included lymphopenia (3/17), hyperglobulinemia (4/17), mild thrombocytopenia (4/17), and lack of antinuclear antibodies in all 17 patients.(1,5) Bryden et al additionally reported anemia.

Histologic findings reported parallel the microscopic findings in our case. They include a moderate to marked lymphocytic interface dermatitis, diffuse hyperkeratosis, basal keratinocyte vacuolation and individual necrosis, exocytosis of lymphocytes into the epithelium, with the interface dermatitis and hyperkeratosis being the most common findings.(1,5)

Primarily CD3 + lymphocytes were identified in the inflammatory infiltrate in the deep epidermis, superficial dermis, hair follicular infundibula, and surrounding sweat glands.(3) In greater than half of the dogs examined, indirect immunofluorescence detected the presence of IgG specific to the follicular basement membranes and specific against sebaceous glands.(1)

Some patients receiving immunomodulatory therapy additionally had generalized demodicosis.(5) Noncutaneous findings consisted of peripheral lymphadenopathy, colitis, eosinophilic and lymphoplasmacytic enteritis.

A recent study evaluating the genetic heritability of this disease showed an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance due to singular nucleotide polymorphism of an as-of-yet unidentified gene on chromosome 18.(8)

Histologic differential diagnoses include sebaceous adenitis, lupus-like drug reactions, lupus erythematosus and erythema multiform.(4) Sebaceous adenititis can be differentiated from the above condition by a lack of an interface dermatitis. Lupus-like drug reactions are reported commonly to otic preparations placed topically and may have a similar histologic appearance. Other forms of lupus erythematosus can be differentiated by the breed and age of the patient and decreased instensity of an inflammatory infiltrate when compared to discoid lupus erythematosis. Erythema multiforme has a similar distribution, is more ulcerative than exfoliative, has a mixed lymphocytic and histiocytic interface dermatitis, may have apoptosis in all levels of the epidermis, and generally occurs in animals greater than one year of age.(4)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Lupus erythematosus occurs in two distinct forms in animals: Systemic lupus erythematous (SLE), which affects multiple tissues, occasionally including the skin; and cutaneous or discoid lupus erythematous (CLE/DLE), in which lesions are localized to the skin. There is some controversy over the designation of DLE; some pathologists prefer the term generalized chronic cutaneous lupus.(2) Exfoliative cutaneous lupus erythematosus (ECLE) of the German shorthaired pointer is a unique form of CLE.(5)

In addition to humans, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is recognized in mice, non-human primates and various domestic animals. SLE is characterized by the loss of B- and T-cell tolerance to self-antigens, resulting in polysystemic inflammation.(6) Patients with SLE produce autoantibodies against a range of nuclear and cytoplasmic components of the cell, including histones, double-stranded DNA, nonhistone proteins bound to RNA, and nucleolar antigens.(2) Autoantibodies and self-antigen complexes deposit within glomeruli, blood vessels, skin and joints, inciting a type III hypersensitivity reaction. To a lesser extent, tissue damage is induced by antibodies directed toward self-antigen on erythrocytes, leukocytes and thrombocytes initiating a type II hypersensitivity reaction, or cell-mediated immunity (type IV hypersensitivity).(7) As a result of all of these variables, SLE generates a wide spectrum of clinical presentations and is often referred to as -Ç-ÿ-Ç-ÿthe great imposter. Affected patients may exhibit a combination of renal disease (glomerulonephritis, interstitial nephritis, vasculitis, and proteinuria), polyarthritis, skin lesions, hematologic disorders, respiratory, or neurologic dysfunction.(6)

Although the definitive cause of SLE remains unknown, numerous endogenous (genetic, hormonal, metabolic, immunologic) and exogenous (drugs, ultraviolet light, infectious agents) factors have been implicated in its pathogenesis.(7) In NZB/W mice, one of the most common strains used in models of SLE, multiple genes have been shown to contribute to the development of SLE, including major histocompatibility complex (MHC) and several non-MHC genes. Recent research has also shown that SLE patients often have hypomethylated DNA, which may lead to an antiMHC class II response and apoptosis of MHC class II antigen presenting cells. In addition to loss of phagocytic cells, genetic deficiencies of complement components may lead to decreased clearance of apoptotic debris and circulating immune complexes, which is another predisposing factor for SLE.(6) Sex hormones, nutrition and both humoral (via autoantibodies) and cell-mediated immunologic factors also contribute to SLE. In dogs, abnormalities in cellular immunity result in lymphopenia characterized by a high CD4+:CD8+ ratio. In normal dogs this ratio is less than 2, while it may reach as high as 6 in dogs with SLE. Additionally, cutaneous disease in affected dogs is exacerbated by ultraviolet light, which may be related to tissue damage and inflammation resulting in elaboration of IL-1, IL-1, IL-2, IL-6, and TNF-b and further damage to the epidermis.(2,7) Alternatively, UV radiation may render DNA immunogenic.(7) Interestingly, ECLE in German shorthaired pointers occurs/progresses without the influence of ultraviolet light.(5) In humans, drugs such as hydralizine, procainamide and D-penicillamine are also associated with SLE, while in animals, drug exposure is a suspected trigger, but specific drugs have not been implicated.(7)

In domestic animals, lupoid skin disorders, such as CLE, are most frequently seen in the dog, often localized to the nose. Lupus-specific histopathological features include hyperkeratosis, epidermal atrophy, basal cell vacuolar degeneration or necrosis (Civatte bodies), basement membrane thickening, mononuclear cell infiltration at the dermoepidermal interface and subepidermal cleft formation. Gross lesions range from alopecia to ulcerative dermatitis.(2,5) On the other hand, skin disorders associated with SLE are non-specific and may not display the lupus specific findings enumerated above.(5)

References:

2. Ginn PE, Mansell JEKL, Rakich PM. Skin and appendages. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 1. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2007:652-655.

3. Gross TL, Ihrke PJ, Walder EJ. Hereditary lupoid dermatosis of the German shorthaired pointer. In: Veterinary Dermatopathology: a Macroscopic and Microscopic Evaluation of Canine and Feline Skin Diseases. St Louis, MO: Mosby Year Book; 1992:2628.

4. Gross TL, Ihrke PJ, Walder EJ, Affolter VK. Skin Diseases of the Dog and Cat: Clinical and Histopathologic Diagnosis. 2nd ed. Ames, IA: Blackwell Science; 2005:59-68.

5. Mauldin EA, Morris DO, Brown DC, Casal ML. Exfoliative cutaneous lupus erythematosus in German shorthaired pointer dogs: disease development, progression and evaluation of three immunomodulatory drugs (ciclosporin, hydroxychloroquine, and adalimumab) in a controlled environment. Vet Dermatol. 2010;21(4):373382.

6. Rottman JB, Willis CR. Mouse models of systemic lupus erythematosus reveal a complex pathogenesis. Vet Pathol. 2010;47:664-676.

7. Snyder PW. Diseases of immunity. In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2012:275-278.

8. Wang P, Zangerl B, Werner P, Mauldin EA, Casal ML. Familial lupus erythematosus (CLE) in the German shorthaired pointer maps to CFA18, a canine orthologue to human CLE. Immunogenetics. 2011;63(4):197-207.