Signalment:

Gross Description:

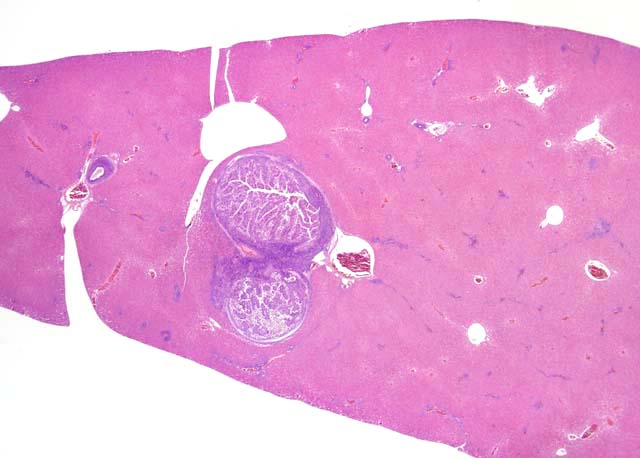

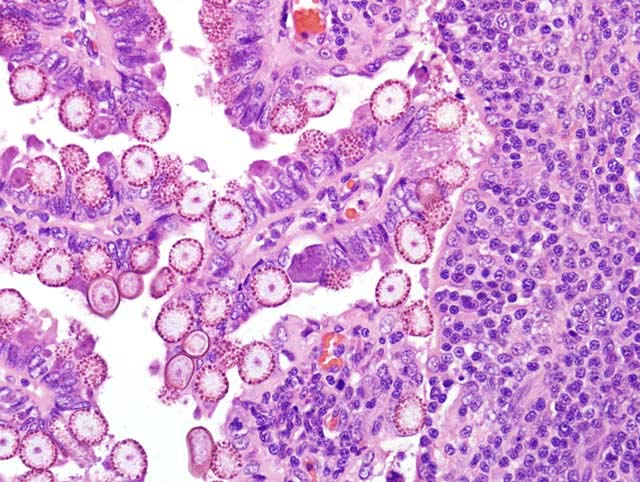

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

The life cycle of E. stiedae is typical of Eimeria spp, in that all Eimeria are host-specific and have a direct life cycle.(2) Oocysts are not infective until sporulation, so ingestion of cecotroph feces does not result in autoinfection. Ingestion of sporulated oocysts (sporocysts) results in release (excystation) of sporozoites in the duodenum. Sporozoites invade the intestinal mucosa, are carried to the liver in the portal veins and/or lymphatics where they enter biliary epithelial cells and multiply asexually by schizogony.(5) Developing schizonts containing merozoites are evident within 3-6 days following infection, and gametogony can be identified eleven days post infection. In gametogony, the final generation merozoites form either macrogametes (female) or microgametes (male). After fertilization, macrogametes develop into oocysts, and enter the intestine through the bile, pass out of the host in the feces, and undergo sporulation. The prepatent period is 14-18 days, and oocysts may be shed in the feces for up to 7 or more weeks. Oocysts of E. stiedae contain 4 sporocysts, each of which contains two sporozoites. They are ovoid to elliptical, 28-42 um by 16-25 um with a micropyle. Sporocysts are 8-10 by 17-18 um and contain a Stieda body.(5)

Eimeria stiedae is common in domestic rabbits throughout the world, as well as cottontail rabbits and hares.(3) It is an important cause of morbidity and mortality in commercial rabbitries (the source of this rabbit) but is rarely seen in laboratory rabbits raised according to strict barrier procedures. E. stiedae infections may be subclinical or manifest as clinical disease, with occasional mortality. Weanling rabbits are most often affected (4) and may exhibit anorexia, lethargy, diarrhea, abdominal enlargement due to hepatomegaly, and icterus.Â

At necropsy, the liver contains variable numbers of raised, linear, bosselated, yellow to gray circumscribed lesions scattered throughout the hepatic parenchyma.(4) In severe cases there is hepatomegaly, with the liver comprising up to 20% of body weight.(5) Microscopically there is marked dilation of bile ducts, extensive portal fibrosis, and a mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate in the portal zones. In affected bile ducts, there is hyperplasia of epithelium with papillary projections, with large numbers of gametocytes and oocysts typically present in affected ducts. The characteristic histologic findings of proliferative biliary changes and coccidial organisms are essentially diagnostic for this disease.

Changes in serum chemistry seen during the acute and convalescent stages of the disease indicate significant metabolic aberrations.(4) There is some evidence that rabbits heavily infected with E. stiedae may have an impaired immune response.Â

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

| Animal | Coccidia | Organ affected |

| Cattle | E. zuernii E. bovis | Distal small intestine Distal small intestine |

| Sheep | E. ovinoidalis E. ashata E. bakuensis E. crandallis | Terminal ileum/ cecum and colon Distal small intestine Distal small intestine Distal small intestine |

| Goats | E. ninakohlyakimovae E. caprina E. christenseni E. arloingi | Cecum and colon Cecum and colon Distal small intestine Distal small intestine |

| Swine | Isospora suis (neonatal pigs) E. scabra (weaners, growers) E. debliecki (weaners, growers) E. spinosa (weaners, growers) | Distal small intestine Distal small intestine Distal small intestine Distal small intestine |

| Equine | E. leuckarti | Small intestine |

| Dogs | C. canis C. ohioensis complex = (C. burrowsi, C. ohioensis, C. neorivolta) | Distal small intestine, large intestine Distal small intestine, large intestine |

| Cats | C. felis C. rivolta | Small intestine, large intestine Small intestine, large intestine |

| Chickens | E. acervulina E. necatrix E. tenella | Small intestine Small intestine Ceca |

References:

2. Gardiner CH, Fayer R, Dubey JP: An Atlas of Protozoan Parasites in Animal Tissues, 1st ed., pp 20-30. USDA Agricultural Research Service Agricultural Handbook Number 651, 1988

3. Levine, ND: Veterinary Protozoology, pp178. Ames, IA, Iowa State University Press, 1985

4. Percy DH, Barthold SW: Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits, pp 288-290. Ames, IA, Blackwell Publishing, 2007

5. Schoeb TR, Cartner SC, Baker RA, Gerrity LW: ï Parasites of rabbits. In: Flynn's Parasites of Laboratory Animals, ed. Baker DG, 2nd ed., pp. 454-457. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2007