Signalment:

Gross Description:

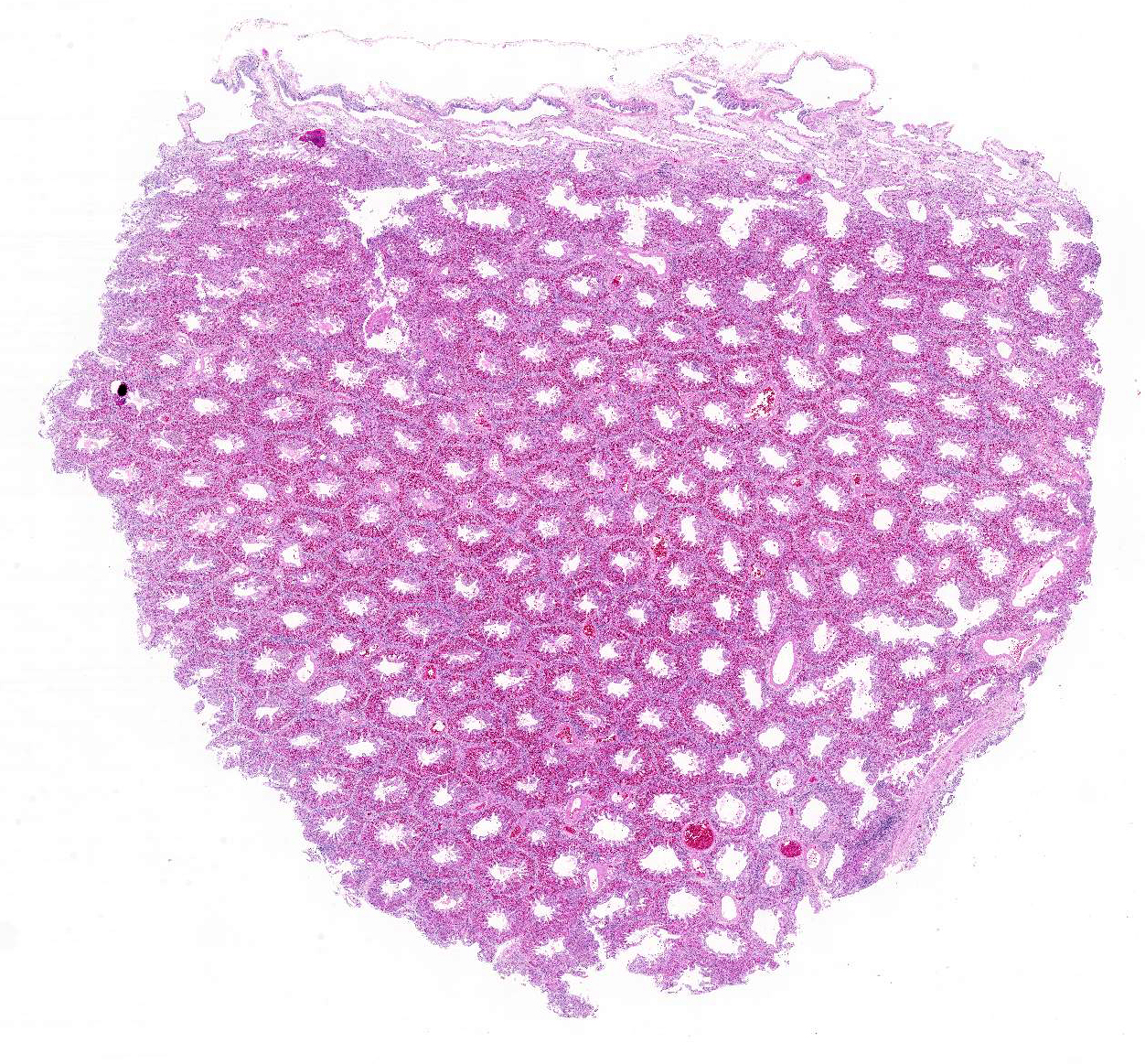

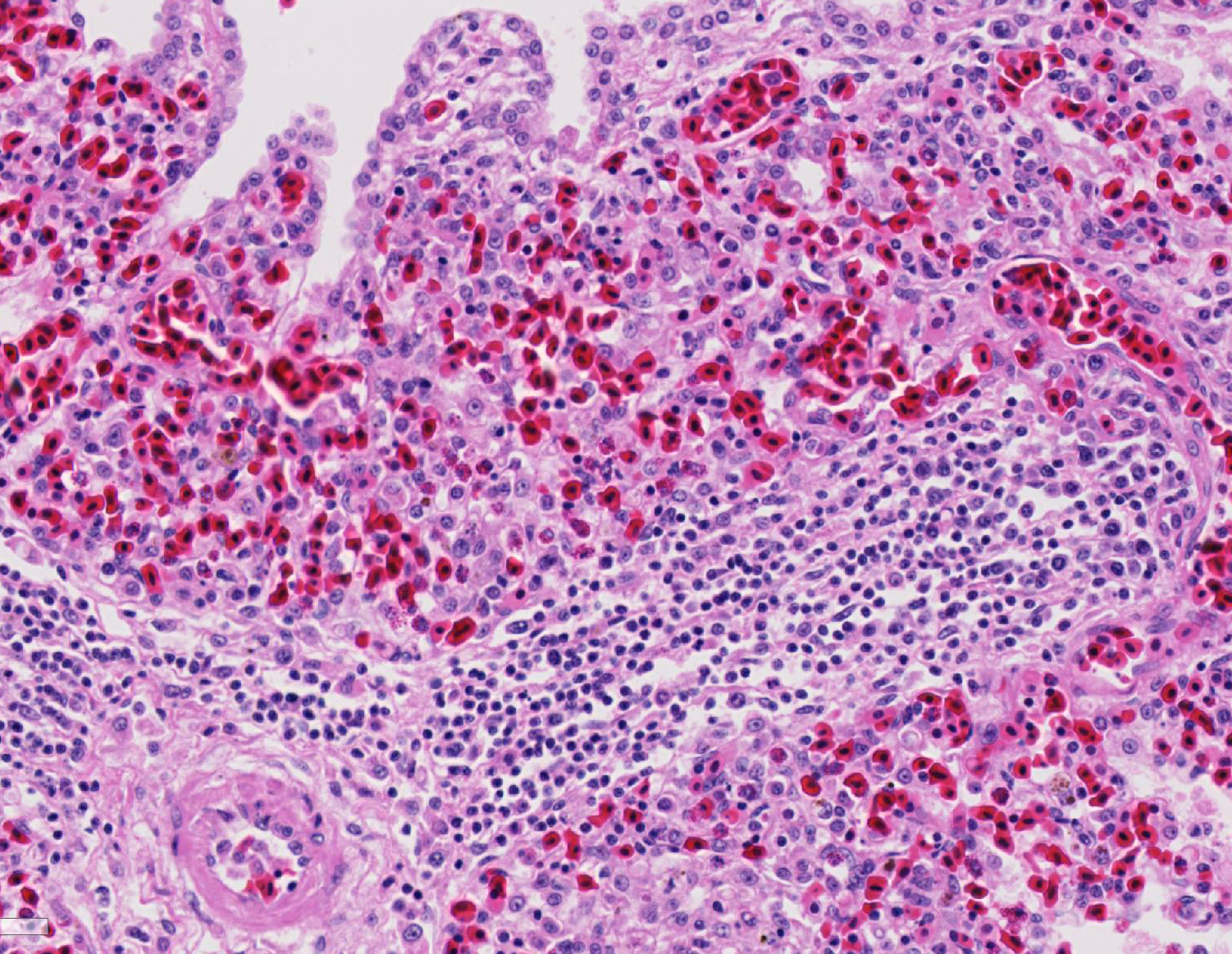

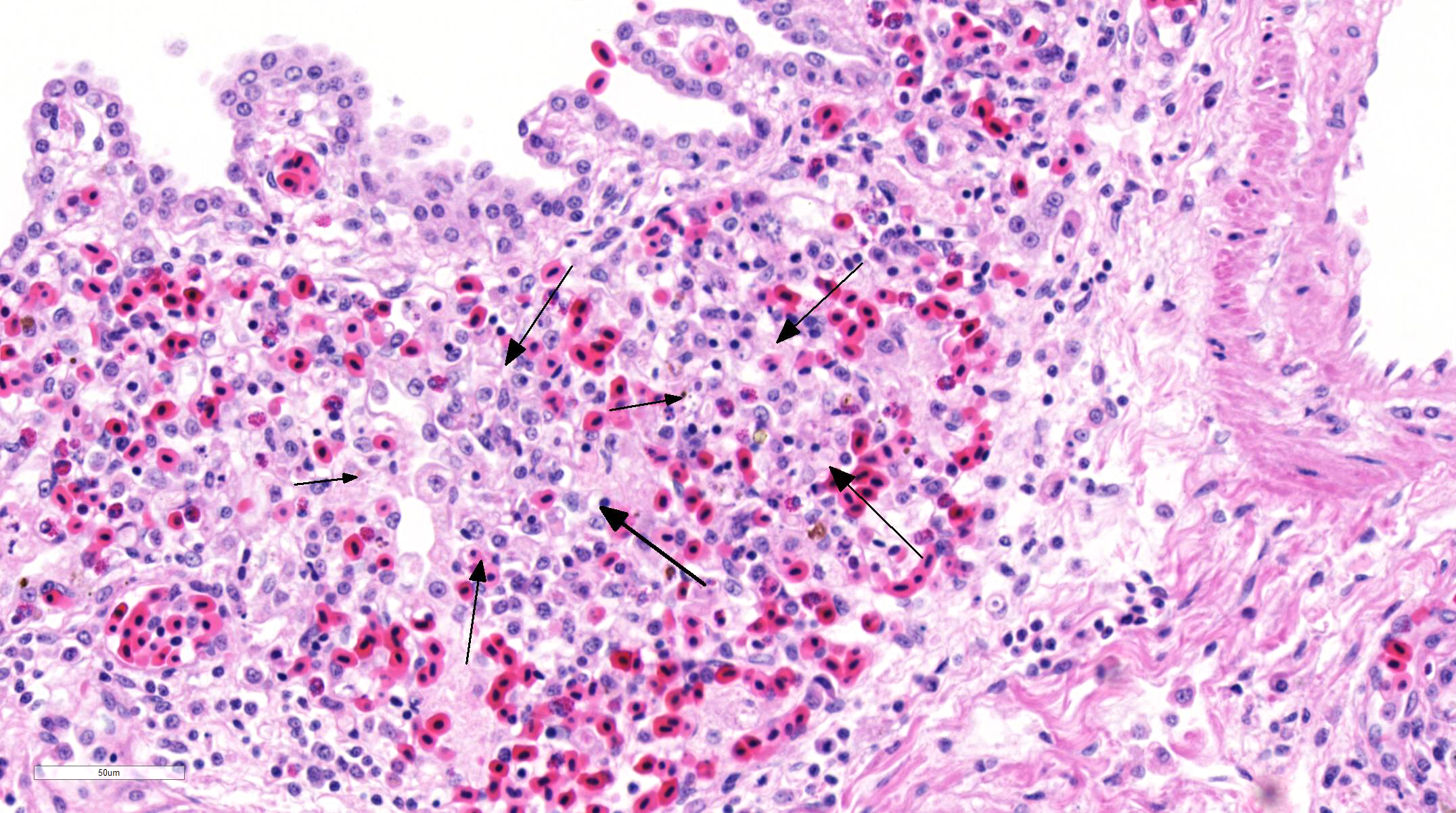

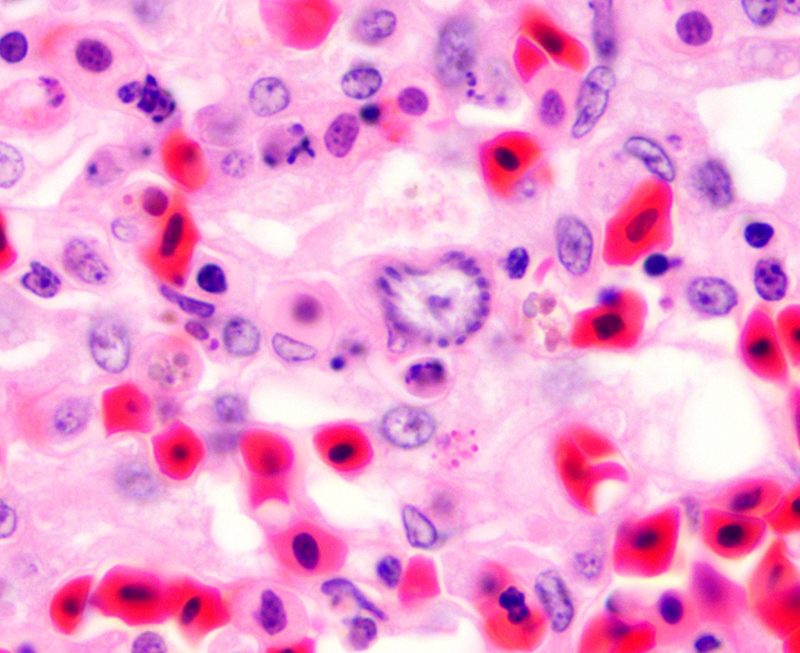

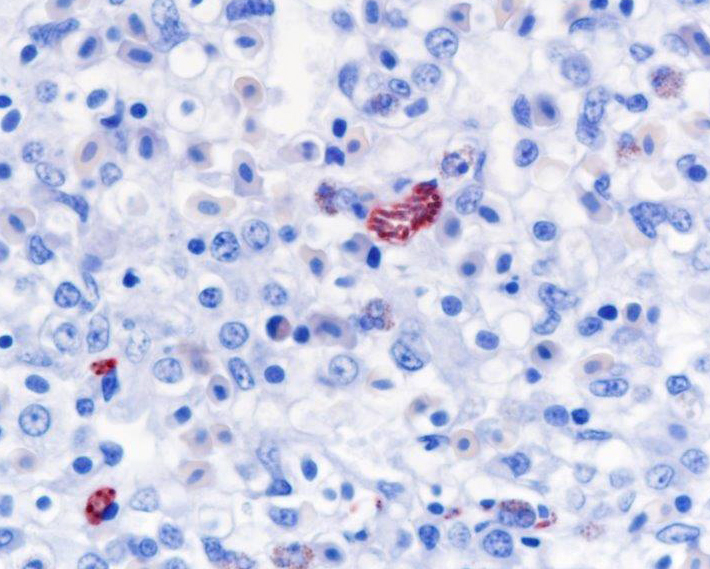

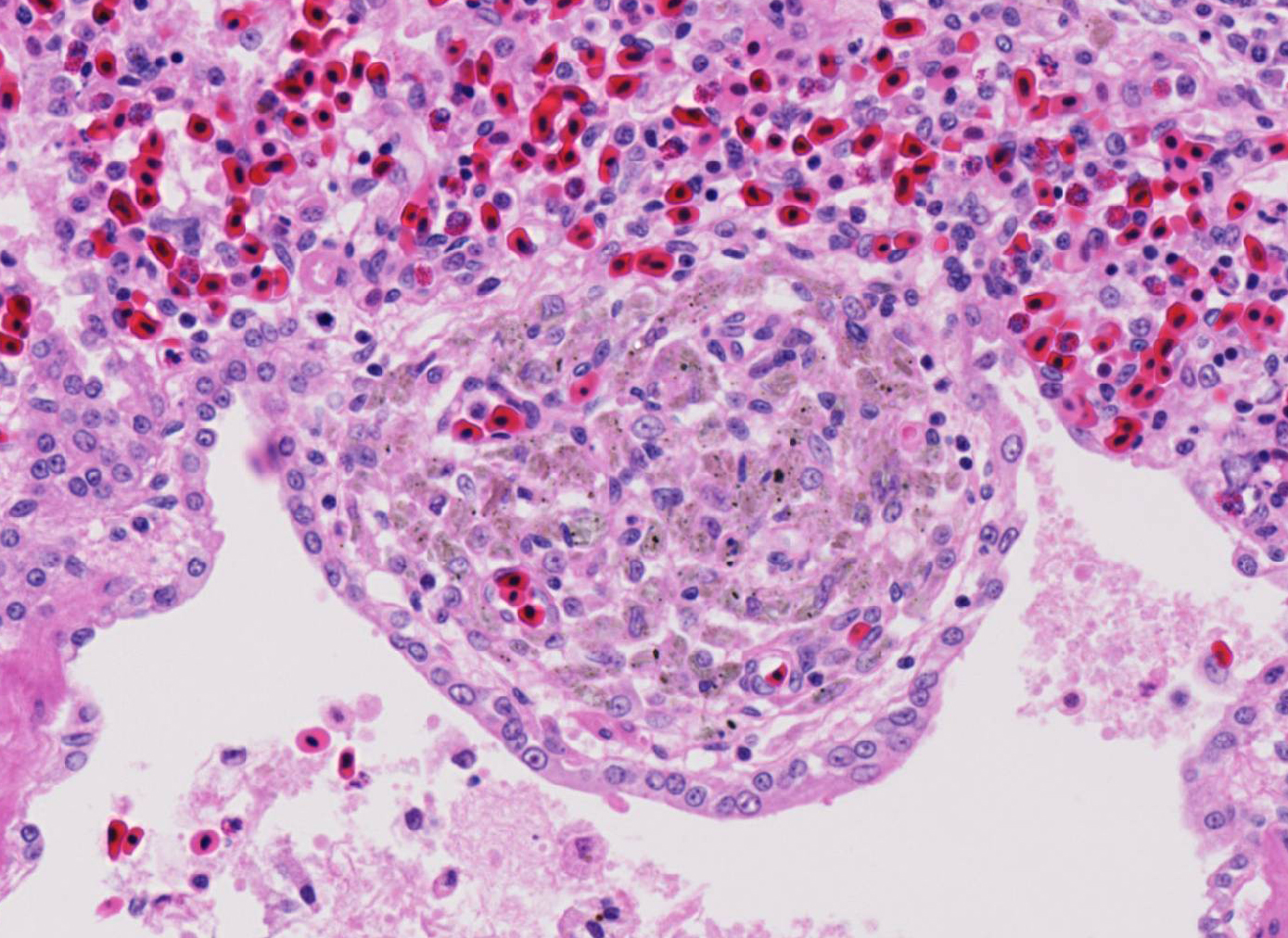

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

In North America, the definitive host for S. falcatula and the closely related S. neurona is the Virginia opossum, Didelphis virginiana, which sheds infective sporocysts in feces.9 Opossums had been seen on the premises of the aquarium institution where this penguin was housed. Infection of various bird species, most naturally grackles and cowbirds, as intermediate hosts is typically through ingestion of food contaminated with opossum feces, but insects such as cockroaches can serve as mechanical vectors.2 In the intermediate host, asexual reproduction (mero-gony/schizogony) occurs in endothelial cells in various tissues but especially in the lung.9,10 The merozoites produced eventually infect skeletal and cardiac muscle cells and form sarcocysts filled with bradyzoites, which are infective to the definitive host upon ingestion of the intermediate host tissue.9 Replication in pulmonary endothelial cells can result in severe interstitial pneumonia, the most common form of fatal infection, although two other clinical forms of disease have been characterized: a neurologic form and a muscular form.14 The neurologic form has been reported in psittacines and raptors.14,15

Fatal pulmonary infection with S. falcatula has been reported most often in psittacines,2-5,14 and this is thought to be the first report in a penguin. The microscopic features of the pneumonia in this penguin were similar to what has been described in other avian species infected with S. falcatula, namely edema, fibrin deposition, congestion, hemorrhage, mononuclear inflammatory infiltrates, endothelial cell lysis, and pneumocyte hyperplasia.7,10,14 The schizonts were rare in this case, occasionally exhibiting a sunburst or somewhat elongated arrangement, but characteristic serpentine forms that conform to pulmonary capillary lumens2-5,7-10,14 were not seen in this penguin. Identification of the infected cells as endothelial cells was not possible in this case from microscopic examination alone. A complete set of tissues was examined histologically from this penguin, including brain, skeletal muscle and heart, but no extrapulmonary schizonts or sarco-cysts were seen. There was, however, a mild lymphohistiocytic portal hepatitis in this bird, which can be seen with S. falcatula infection,7,8 and for which no other etiology was identified.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Sporulated oocysts are then ingested by susceptible intermediate hosts, such as herbivorous mammals or birds. After ingestion by the intermediate host, sporozoites excyst in the intestine and undergo two generations of asexual merogony (schizogony). Sporozoites are released and first migrate to endothelial cells where they undergo the first two generation of asexual reproduction, resulting in the development of meronts.3,9,11,15 In birds, merogony is most pronounced in vascular endothelial cells within the lungs. Pulmonary capillary endothelial cells can become markedly swollen and inflamed, leading to lymphohistiocytic vasculitis, airway edema, interstitial pneumonia, and even vascular obstruction in birds with a heavy protozoan burden.11,15 Merogony has also been reported in vessels of the liver, pancreas, spleen, adrenal glands and heart.11In animals that survive the maturation of the second generation of meronts, merozoites are liberated from meronts within capillaries and enter circulating mononuclear cells. Merozoites then undergo endodyogeny and enter muscle fibers to eventually form sarcocysts containing bradyzoites. They will remain encysted and viable in the muscular or nervous tissue until they are ingested by the definitive host to complete the lifecycle. There are over 90 Sarcocystis sp. known to infect mammals, birds, and reptiles. The vast majority of species are considered non-pathogenic; however, some species, such as S. falcatula in birds, are associated with severe clinical disease in the intermediate host.3,4,11,15

As mentioned by the contributor, the only known definitive host for this protozoan in North America is the opossum (Didelphis virginiana). Most Sarcocystis sp. infect a specific intermediate host; however, Sarcocystis falcatula is unique in that it can infect a heterogeneous population of avian intermediate hosts from numerous avian species (Passeriformes, Psittaciformes, and Columbiformes).4,9,11,15 Birds become infected by eating feed contaminated with opossum feces containing infective oocysts or sporocysts or ingestion of cockroaches, which is the main mechanical vector for the parasite.2

References:

1. Barr BC, Conrad PA, Dubey JP, Anderson ML. Neospora-like encephalomyelitis in a calf: Pathology, ultrastructure and immunoreactivity. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1991;3:39-46.

2. Clubb SL, Frenkel JK. Sarcocystis falcatula of opossums: Transmission by cockroaches with fatal pulmonary disease in psittacine birds. J Parasitol. 1992; 78(1):116-124.

3. Gardiner CH, Fayer R, Dubey JP. Apicomplexa. In: An Atlas of Protozoan Parasites in Animal Tissues. 2nd ed. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, American Registry of Pathology, Washington DC; 1998:20-42.

4. Godoy SN, De Paula CD, Cubas ZS, Matushima ER, Catão-Dias JL. Occurrence of Sarcocystis falcatula in captive psittacine birds in Brazil. J Avian Med Surg. 2009; 23(1):18-23.

5. Hillyer EV, Anderson MP, Greiner EC, Atkinson CT, Frenkel JK. An outbreak of Sarcocystis in a collection of psittacines. J Zoo Wildlife Med. 1991;22(4):434-445.

6. Ploeg M, Ultee T, Kik M. Disseminated toxoplasmosis in black-footed penguins (Spheniscus demersus). Avian Dis. 2011; 55:701-703.

7. Smith JH, Neill PJG, Dillard III EA, Box ED. Pathology of experimental Sarcocystis falcatula infections of canaries (Serinus canarius) and pigeons (Columba livia). J Parasitol. 1990; 76(1):59-68.

8. Smith JH, Neill PJG, Box ED. Pathogenesis of Sarcocystis falcatula (Apicomplexa: Sarcocystidae) in the budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulates). III. Pathologic and quantitative parasitologic analysis of extrapulmonary disease. J Parasitol. 1989; 75(2):270-287.

9. Smith JH, Meier JL, Neill PJG, Box ED. Pathogenesis of Sarcocystis falcatula in the budgerigar. I. Early pulmonary schizogony. Lab Invest. 1987; 56(1): 60-71.

10. Smith JH, Meier JL, Neill PJG, Box ED. Pathogenesis of Sarcocystis falcatula in the budgerigar. II. Pulmonary pathology. Lab Invest. 1987; 56(1):72-84.

11. Sundermann CA, Estridge BH, Branton MS, Bridgman CR, Lindsay DS. Immunohistochemical diagnosis of Toxoplasma gondii: potential for cross-reactivity with Neospora caninum. J Parasitol. 1997; 83(3):440-443.

12. Uzêda RS, Schares G, Ortega-Mora LM, et al. Combination of monoclonal antibodies improves immuno-histochemical diagnosis of Neospora caninum. Vet Parasitol. 2013; 197:477-486.

13. Vanstreels RET, da Silva-Filho RP, Kolesnikovas CKM, et al. Epidemiology and pathology of avian malaria in penguins undergoing rehabilitation in Brazil. Vet Res. 2015; 46:30.

14. Villar D, Kramer M, Howard L, Hammond E, Cray C, Latimer K. Clinical presentation and pathology of sarcocystosis in psittaciform birds: 11 cases. Avian Dis. 2008; 52:187-194.

15. Wünschmann A, Rejmanek D, Conrad PA, et al. Natural fatal Sarcocystis falcatula infections in free-ranging eagles in North America. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2010; 22:282-289.