Conference 25, Case 1

Signalment:

3-year-old, 9-month pregnant, female, Jersey (Bos taurus taurus).

History:

The cow was dried o? on June 28, 2022. She had been doing well until August 17, 2022, when she was found recumbent and was diagnosed with possible pink eye. She was treated with aspirin, penicillin, and dexamethasone subconjunctivally. On August 18, 2022, she remained recumbent, began convulsing, and died at 9:30 am. She was submitted for postmortem examination by 11:00 am on the same day.

Gross Pathology:

Fair body condition with mild muscle mass, minimal external adipose stores, and moderate internal adipose stores in all expected locations. Avulsion of the lateral right hind limb dew claw; multifocal 2 to 15 cm diameter area abrasions on the right hip and on the lateral aspect of the right fore limb; and, a 15 x 11 cm area of subcutaneous edema and a 35 x 20 cm area of subcutaneous hemorrhage on the right thorax over the ribs and right shoulder.

Thoracic negative pressure and mild, serosanguineous pleural effusion. Multifocal thoracic cranioventral fibrous adhesions that span between lung, pericardial sac, diaphragm, and body wall. Mild ventrocranial laryngeal edema. Severe, diffuse, frothy, white foam extending from the larynx to the secondary bronchi. Mild to moderate, white frothy fluid oozes from the lungs on the cut section. Multifocal epicardial and left ventricular endocardial petechiae. A focal, 5.5 x 3 cm hemorrhage at the base of the right atrium overlaying adipose tissue.

A focal well-demarcated, 4 x 1 cm subacute healing ulcer on the right lateral aspect of the tongue. Rumen has decreased dry ingesta (dehydrated) with admixed birdshot and rocks. No magnet. There is expected postmortem rumen mucosal sloughing.

The abomasum contains rocks admixed with green organic material and the mucosa has multifocal occasional subacute ulcers. The biliary tract is patent with normal bile. There is a fibrous adhesion of the right liver lobe to the omentum. The liver is moderately congested.

The right caudal mammary quarter has a thick, viscous, white-to-tan discharge without flocculent material, and on section, the mammary gland is pale tan and oozes a cloudy white thick fluid. The supramammary lymph nodes are enlarged and wet.

The subdural space of the brain and the cervical spinal cord has viscous, translucent to yellow serous meningeal fluid and multifocal hemorrhage. The right ventrocranial aspect of the cerebral frontal lobe and olfactory lobe and bulb are regionally tan to yellow, soft, and friable (encephalomalacia). The area’s meninges are thickened by fibrin, edema, and hemorrhage.

The left eye has a regional soft expansion of the conjunctiva (iatrogenic) and is overlaid by at least 3 thin white linear nematodes (favor Thelazia gulosa).

FETUS: The left uterine horn has a single female fetus. The fetus is well muscled with abundant adipose stores. The maternal aspect of the chorioallantois is overlaid by multifocal brown, mucoid material. There are multiple (< 5) small (< 0.5 cm), white, discrete, firm, and focal nodules on the amniotic sac. The fetus is 18.4 kg, 72.5 cm from crown to rump, has erupted incisors, and is fully haired with eyelashes (9 month, near term). No thoracic negative pressure and lung sections sink in formalin. The thoracic cavity has mild, serosanguineous fluid. The right lateral and cranial aspect of the liver has a large 10 x 6 cm cyst. When cut, the cyst oozes red-tinged serous fluid with scant fibrin. There is focal hemorrhage of the ruminal serosa and regional suffusive hemorrhage on the right ventricle epicardium.

Laboratory Results:

1) A multiplex real-time PCR performed by the USA CDC on fresh brain from the right frontal/olfactory lobe was positive for Naegleria fowleri and negative for Acanthamoeba spp. and Balamuthia mandrillaris.

2) Immunohistochemistry performed by the USA CDC on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded right frontal/olfactory lobe was immunoreactive for free-living amoeba and Naegleria-specific antibodies.

3) Three environment water samples were submitted to Biological Consulting Services of North Florida Inc. for N. fowleri analysis. Water from the concrete pond and from the drinking trough of an adjacent pen did not detect N. fowleri. Water from the drinking trough of the pen that housed the affected cow was positive for N. fowleri.

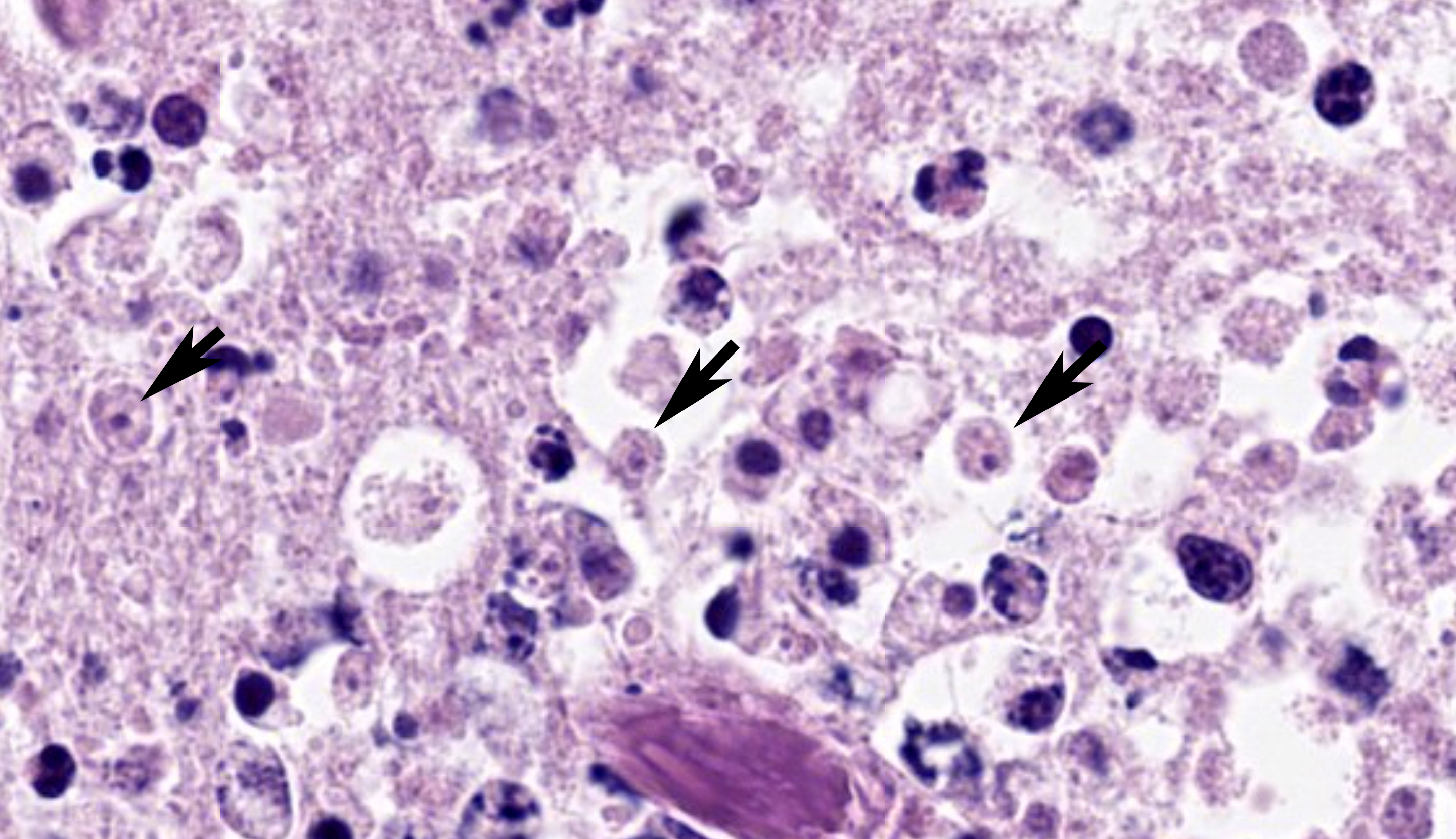

Microscopic Description:

Brain, right frontal lobe/olfactory lobe: Involving 40% of the section and extending to the leptomeninges, there is locally extensive encephalomalacia with fibrin thrombi, vasculitis, vascular fibrinoid degeneration, neutrophils, cellular debris, hemorrhage, and fibrin. Within these areas, often perivascular admixed with neutrophils, are ovoid to polygonal 8-10 um diameter organisms that have small 1-2 um nuclei that contain a single central nucleolus (karyosome) with a granular amphophilic vacuolated cytoplasm (amoeba trophozoites). Bordering the area of malacia are streams of degenerate neutrophils and fibrin, and within the adjacent intact neuropa

Cranium, ox: The remnant neuroparenchyma of the right frontal/olfactory lobe is soft, friable, tan to light yellow, and has multifocal hemorrhage (encephalomalacia). The adjacent subdura is thickened by fibrin and edema. (Photo courtesy of: Midwestern University, College of Veterinary Medicine, Diagnostic Pathology Center. https://www.mwuanimalhealth.com/diagnostic-pathology-center.)

The cow’s drinking water trough that tested positive for N. fowleri was heavily fouled by organic debris (Photo courtesy of: Midwestern University, College of Veterinary Medicine, Diagnostic Pathology Center. https://www.mwuanimalhealth.com/diagnostic-pathology-center.)

renchyma and leptomeninges, are frequent dense perivascular cuffs of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes with variable spongy change, fibrin, vascular fibrinoid degeneration, reactive vascular endothelium, and hemorrhage.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Brain, frontal right lobe/olfactory bulb: Meningoencephalitis, necrotizing, suppurative, mononuclear, multifocal, severe, acute to subacute, with intralesional amoeba trophozoites

Contributor’s Comment: The cow’s morbidity and mortality were due to necrotizing encephalitis caused by Naegleria fowleri, a eukaryotic, amphizoic, thermophilic, and free-living amoeba that is ubiquitous in the environment. Multiplex PCR performed on fresh brain from the right frontal and olfactory lobe confirmed N. fowleri. Immunohistochemistry performed on a formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded section of the affected brain detected intralesional N. fowleri. Analysis of the cow’s drinking water visually detected amoeba trophozoites, and PCR confirmed N. fowleri, thereby determining the probable environmental source. Although the necrotizing inflammation was most severe in the right frontal and olfactory lobes, histopathology recognized similar lesions with fewer amoeba in the ventral periventricular cerebellum, brainstem, fourth ventricle choroid plexus, and cervical spinal cord. The distribution of these secondary inflammatory nidi suggests the amoebae spread via the cerebrospinal fluid following primary invasion of the right olfactory bulb.

Naegleria fowleri, Balamuthia mandrillaris, Acanthamoeba spp., and Sappinia pedata are pathogenic free-living amoebae that naturally cause central nervous system (CNS) disease in mammals.3,6 These ubiquitous amoebae are opportunistic, target immunocompetent and immunosuppressed hosts, and may occupy soil, air, and water.3,6 Infections occur in humans and animals; however, S. pedata has

|

Cerebrum, ox: There is necrosis of the neuroparenchyma with abundant perivascular inflammation. (HE, 135X) |

occurred in only one human case of encephalitis.4,6 Unlike other amoeba, N. fowleri, the cause of fulminating primary amoebic meningoencephalitis, causes encephalitis following a direct entry into the CNS via the olfactory neuroepithelium, and the resulting lesions lack intralesional cysts.6

Naegleria fowleri naturally subsists on phagocytosed bacteria and thrives in unchlorinated warm bodies of water (upwards of 45ºC), including freshwater pools, puddles, lakes, rivers, hot springs, aquaria, sewage, irrigation canals, ponds, irrigation ditches, and thermally polluted effluents of power plants.1,6 Resistant cysts form during adverse environmental conditions; otherwise, the protozoa is in a transitory flagellate stage or, more frequently, is an infectious amoeboid trophozoite equipped with a vesicular nucleus that has a single central nucleolus (karyosome).6 Trophozoites reproduce by binary fission and will become cysts if food is lacking or the environment impairs growth.6 Human and animal infections develop when nasal passages are inadvertently (e.g., during aquatic activities) or purposefully (e.g., nasal flush) exposed to warm unchlorinated or inadequately chlorinated water harboring infectious trophozoites. Trophozoites are first phagocytosed by the sustentacular cells of the olfactory neuroepithelium, then migrate through the cribriform plate, invade the leptomeninges, and finally, access the rostral neuroparenchyma where they can proliferate and potentially spread to other neuroanatomical locations.6 Generally, onset of disease is rapid, as soon as 24 hours, and death usually occurs within a week.6 This cow was likely exposed to N. fowleri during drinking activities and perhaps inadvertently snorted contaminated water or transferred amoeba to the nostrils during licking, which allowed trophozoites to reach and invade the right cribriform plate and subsequently cause malacia of the right frontal/olfactory lobe. Although the cow’s drinking water was purported to be chlorinated, the trough contained warm stagnant water, there was surface scum, and a thick layer of organic debris lined the bottom-collectively, these factors probably inhibited efficient chloramination and facilitated the survival of N. fowleri trophozoites.

Meningoencephalitis due to N. fowleri is reported in cattle from Costa Rica, the state of Paraiba, Brazil, California, USA, and now Arizona, USA.2,4,5 As in this case, the incidence of N. fowleri in California cows correlated with warm summer temperatures, acute CNS clinical signs, olfactory and cerebellar necrosuppurative lesions, and the probable exposure to trophozoites in drinking water.2

Although uncommon in cattle, amoebic meningoencephalitis caused by N. fowleri is an important differential diagnosis of an acutely neurologic cow that is most likely during the summer in a geographic area with high ambient temperatures. Other important and more common differential diagnoses for neurologic disease in cattle include rabies virus, polioencephalomalacia, lead toxicosis, salt toxicity, thrombotic meningoencephalitis, cerebral abscess, and bacterial meningitis.2

Contributing Institution:

Midwestern University, College of Veterinary Medicine, Diagnostic Pathology Center

https://www.mwuanimalhealth.com/diagnostic-pathology-center

JPC Morphologic Diagnosis: Cerebrum: Meningoencephalitis, necrotizing and suppurative, focally extensive, subacute, severe, with vasculitis, thrombosis, and numerous amoebic trophozoites.

JPC Comment: This week’s moderator was Dr. Jey Koehler from Auburn University who selected an array of neuropathology cases to discuss with conference participants. Her preconference lecture on evaluation of the nervous system proved helpful in refining descriptive elements and recognizing important artifacts within the brain and spinal cord – herein we capture some of these pearls of wisdom in our discussion.

This first case leaves little doubt from subgross where the lesion is on the slide, though there are several descriptive features not to miss on higher magnification. The cause of the abundant necrotizing inflammation is characteristic with amoeba having distinct, round central nuclei and round karyosomes that were best appreciated with the iris diaphragm closed down. In comparison to Balamuthia and Acanthamoeba, we did not note any tissue cysts, though Dr. Koehler posited that Naegleria infection is rapidly fatal to most (all?) animals, leaving little time for these to develop.8 The marked fibrinoid vasculitis and many fibrin thrombi reflect both direct damage to vessels from secreted amoebic proteases and trogocytosis of neural tissue (literally, nibbling of host cells to gain nutrients!)7 in addition to the indirect ischemic effects. The large presence of neutrophils reflects both amoebic recruitment and response to cellular injury. Dr. Koehler emphasized that remembering the number of neutrophils (granulocytes) within the neuroparenchyma was easy – that number should be zero (or else prompt you to look further for why they are there). For another example of amoebic disease (Entamoeba) with necrotizing inflammation in a colobus monkey, see Conference 9, Case 1 from this year.

The contributor provides an interesting take on Naegleria that is cemented by a solid gross photo of the waterer for this animal. Absent this highly suggestive image, conference participants also discussed other causes of focal encephalitis which included dehorning injury/trauma, abscessation (e.g. from a nose ring), bovine herpesviruses, Histophilus, and angioinvasive fungi (Aspergillus). We did not identify any other agents present in section, however.

Finally, conference participants enjoyed an enlightening discourse on the nature of necrosis within the brain, encephalitis, and true malacia. We differed from the contributor’s interpretation of this case slightly in that we feel that the separation of the neuroparenchyma is largely artifactual (i.e. the process of cutting a soft brain) versus true cavitation due to necrosis. Dr. Koehler emphasized that thin gliovascular strands extending between adjacent vessels within increased clear space histologically are consistent with malacia (see Conference 5, Case 4 of the current year for an excellent example in a SV40-infected macaque) which was not observed here and not consistent with the mechanism of injury expected for Naegleria. We briefly debated whether this case represents an encephalitis versus meningoencephalitis given the minimal involvement of the overlying meninges and the notion that observed changes may simply extend outward towards the meninges. We ultimately accepted the contributor’s note that this lesion was distributed multifocally and features may have differed in other sections.

References:

- Blair B, Sarkar P, Bright KR, Marciano-Cabral F, Gerba CP. Naegleria fowleri in Well Water. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(9):1499-1501.

- Daft BM, Visvesvara GS, Read DH, Kinde H, Uzal FA, Manzer MD. Seasonal meningoencephalitis in Holstein cattle caused by Naegleria fowleri. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2005;17:605-609.

- Hawkins SJ, Struthers JD, Phair K, et al. Diagnostic evaluation of fatal Balamuthia mandrillaris meningoencephalitis in a captive Bornean orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus) with identification of potential environmental source and evidence of chronic exposure. Primates. 2021;62(1):51-61.

- Pimentel LA, Dantas AF, Uzal F, Riet-Correa F. Meningoencephalitis caused by Naegleria fowleri in cattle of northeast Brazil. Res Vet Sci. 2012;93(2):811-812.

- Visvesvara GS, De Jonckheere JF, Sriram R, Daft B. Isolation and Molecular Typing of Naegleria fowleri from the Brain of a Cow That Died of Primary Amebic Meningoencephalitis. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(8):4203-4204.

- Visvesvara G, Moura H, Schuster F. Pathogenic and opportunistic free-living amoebae: Acanthamoeba spp., Balamuthia mandrillaris, Naegleria fowleri, and Sappinia diploidea. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2007;50:1–26.

- Herman EK, Greninger A, van der Giezen M, et al. Genomics and transcriptomics yields a system-level view of the biology of the pathogen Naegleria fowleri. BMC Biol. 2021 Jul 22;19(1):142.

- Fouque E, et al. Cellular, biochemical, and molecular changes during encystment of free-living amoebae. Eukaryot Cell. 2012 Apr;11(4):382-7.