Signalment:

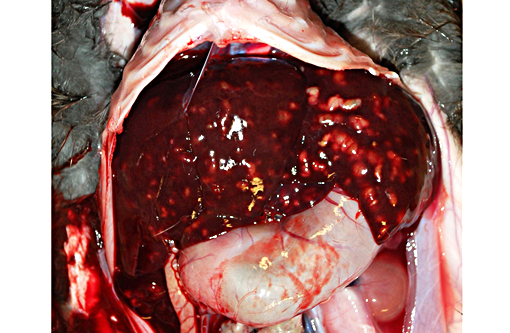

Gross Description:

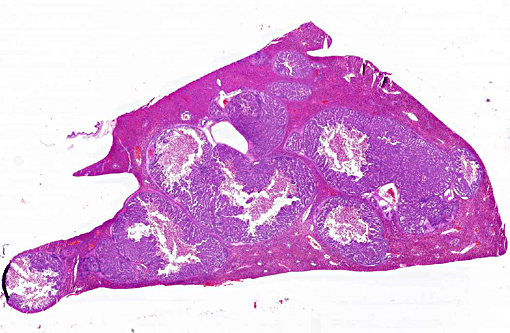

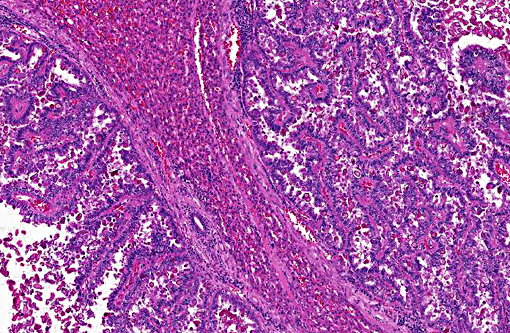

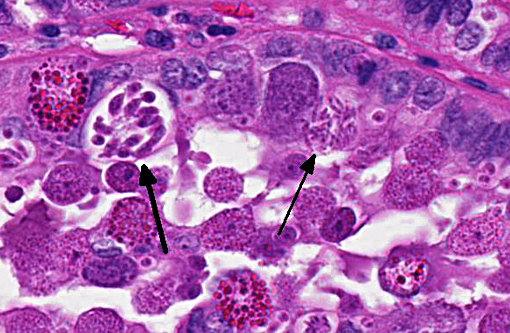

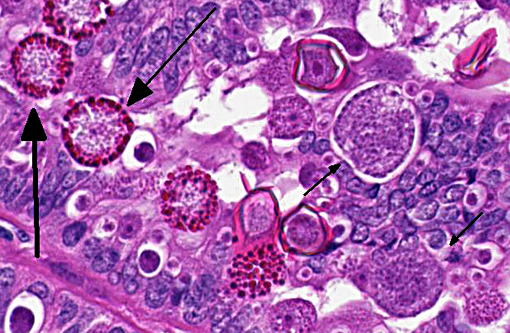

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

1. Marked proliferative and nonsuppurative cholangitis with large numbers of intralesional coccidial organisms.Â

2. Marked hepatic atrophy.Â

3. Ascites.

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Infection with Eimeria stiedae is usually subclinical and historically, hepatic coccidiosis has been associated with significant condemnations of livers from meat-type rabbits at processing but not with elevated mortality during grow-out.(7) However, if young, na+�-�ve rabbits are exposed to high enough levels of sporulated oocysts, clinical disease including anorexia, poor weight gain, weight loss, development of a distended abdomens, diarrhea and elevated mortality can occur.(2,7) In this particular situation, only the rabbits being reared on the floor were clinically affected and although the rabbits submitted for postmortem did not have diarrhea, histologically, they also had significant numbers of coccidial organisms within the intestinal mucosa and results of flotations conducted on feces from all rabbits indicated large numbers of mixed Eimeria spp. oocysts. Despite weekly cleaning and rebedding, the environment was heavily contaminated with coccidial oocysts and these rabbits were being continually challenged with both intestinal and hepatic coccidia.

Recommendations for the control of hepatic coccidiosis parallel the recommendations for control of intestinal coccidiosis, and sanitation is of great importance.(2,7) Coccidial oocysts are extremely resistant to environmental influences and no commonly available disinfectants will kill them. Removal of organic material from cages, feed pans and around waterers where oocysts can reside can help reduce the challenge.(7) Rabbits can develop long-lasting immunity to Eimeria stiedae as long as they are not exposed to an excessively high dose initially and are immunocompetent.(2)

With the advent of increased interest in raising small groups of rabbits and allowing them access to the ground, hepatic coccidiosis may re-emerge as a clinical disease.Â

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

The oocyst initially contains a single cell called a sporont, and through a process known as sporulation or sporogony, the sporont develops into four sporocysts, each with two sporozoites. This appearance of the sporulated oocyst (4 sporocysts and 8 sporozoites) is a distinguishing feature of Eimeria spp. from other coccidian apicomplexans.(1) The sporulated oocyst is now infectious, and sporozoites will be released when ingested by the host.(1) The sporozoites invade epithelial cells and round up to become trophozoites which are the growing forms.(3) Trophozoites undergo asexual nuclear division, called both schizogony and merogony, to form a schizont/meront.(1,3,4) These two terms are used synonymously in most references of this stage, with the term schizogony referring to multiple nuclear divisions (as occurs in Eimeria spp. while merogony equates with nonspecific asexual division. Each schizont develops within it numerous merozoites, which following rupture of the host epithelial cell, are released to infect additional cells and subsequently develop into additional schizonts.(4) This process repeats over a variable number of generations depending on the individual species. For reasons still unknown, eventually some merozoites will infect epithelial cells and begin the sexual phase of the life cycle called gametogony.(3) The majority become females (macrogametocytes), while some become males (microgametocytes) which form numerous biflagellate microgametes within epithelial cells.(4) Each microgamete can fertilize a macrogamete to form a zygote known as the oocyst, which are then shed in the feces.(4) Among the phases of this elaborate life cycle, conference participants identified oocysts, schizonts containing merozoites, micro- and macrogametocytes, and micro- and macrogametes in abundance in this case.Â

In hepatic coccidiosis, this life cycle still begins within gastrointestinal epithelial cells, particularly in the duodenum. Following exposure, sporozoites have been documented in the regional lymph nodes within 12 hours, in bone marrow within 24 hours, and in the liver within 48 hours.(6,7) Thus, spread by both hematogenous and lymphatic routes have been proposed. Additionally, the organism may infect mononuclear cells which aid in their dissemination.(7) Following gametogony in the biliary epithelium, the oocysts are shed in the bile and passed to the intestines.(7) Numerous oocysts are present in multiple blood vessels in many sections, a finding most participants attributed to an artifact of processing.Â

Eimeria stiedae have a characteristic appearance to the oocyst, with a thinning of the opercula that distinguishes it from all other coccidians in rabbits. There are eight other species of Eimeria known to infect rabbits and mixed infections are common, as demonstrated by the fecal results obtained in this case.Â

Intestinal Coccidia of Rabbits

| HIghly Pathogenic | Intermediately pathogenic | Minimally Pathogenic |

| E. flavescens | E. magna | E. media |

| E. intestinalis | E. irresidua | E. perforans |

| E. piriformis | E. neoleporis |

References:

1. Gardiner CH, Fayer R, Dubey JP. An Atlas of Protozoan Parasites in Animal Tissues. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology/ American Registry of Pathology; 1998.

2. Harkness, JE, PV Turner, S VandeWoude, Wheler CL. Coccidosis (Hepatic) in Rabbits. In: Harkness and Wagners Biology and Medicine of Rabbits and Rodents. 5th ed. Ames, Iowa: Blackwell Publishing; 2010:272-275.Â

3. Kreier JP, Baker JR. Parasitic Protozoa. Winchester, MA: Allen & Unwin; 1987:134.

4. Levine ND. Protozoan Parasites of Domestic Animals and of Man. 2nd ed. Minneapolis, MN: Burgess Publishing Co; 1973:156-245.

5. Morgan KJ, Alley MR, Pomroy WE, Gartrell BD, Castro I, Howe L. Extra-intestinal coccidiosis in the kiwi (Apteryx spp.). Avian Pathol. 2013;42(2):137-146.

6. Owen D. Life cycle of Eimeria stiedae. Nature. 1970;227:304.

7. Percy DH, Barthold SW. Rabbit. In: Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits. 3rd ed. Ames, Iowa, USA: Blackwell Publishing; 2007:253-307.