Wednesday Slide Conference, 2025-2026, Conference 5, Case 2

Signalment:

5 years old, male intact, cynomolgus macaque (Macaca fascicularis)History:

A 5-year-old training animal from the stock colony, not actively enrolled in a study presented with decreased activity and reactivity and was emaciated, pale, dehydrated, and hypothermic. Cardiothoracic examination revealed increased respiratory effort, muffled cardiac sounds with a suspected systolic murmur, and thoracic edema. The animal was euthanized in extremis.Gross Pathology:

Lung: Discoloration, dark, brown, diffuse Heart: Irregular surface, right AV valve, 100% affectedLaboratory Results:

Aerobic bacterial culture, heart: Moderate Escherichia coli, Few Staphylococcus warneri, Few Streptococcus mitisMicroscopic Description:

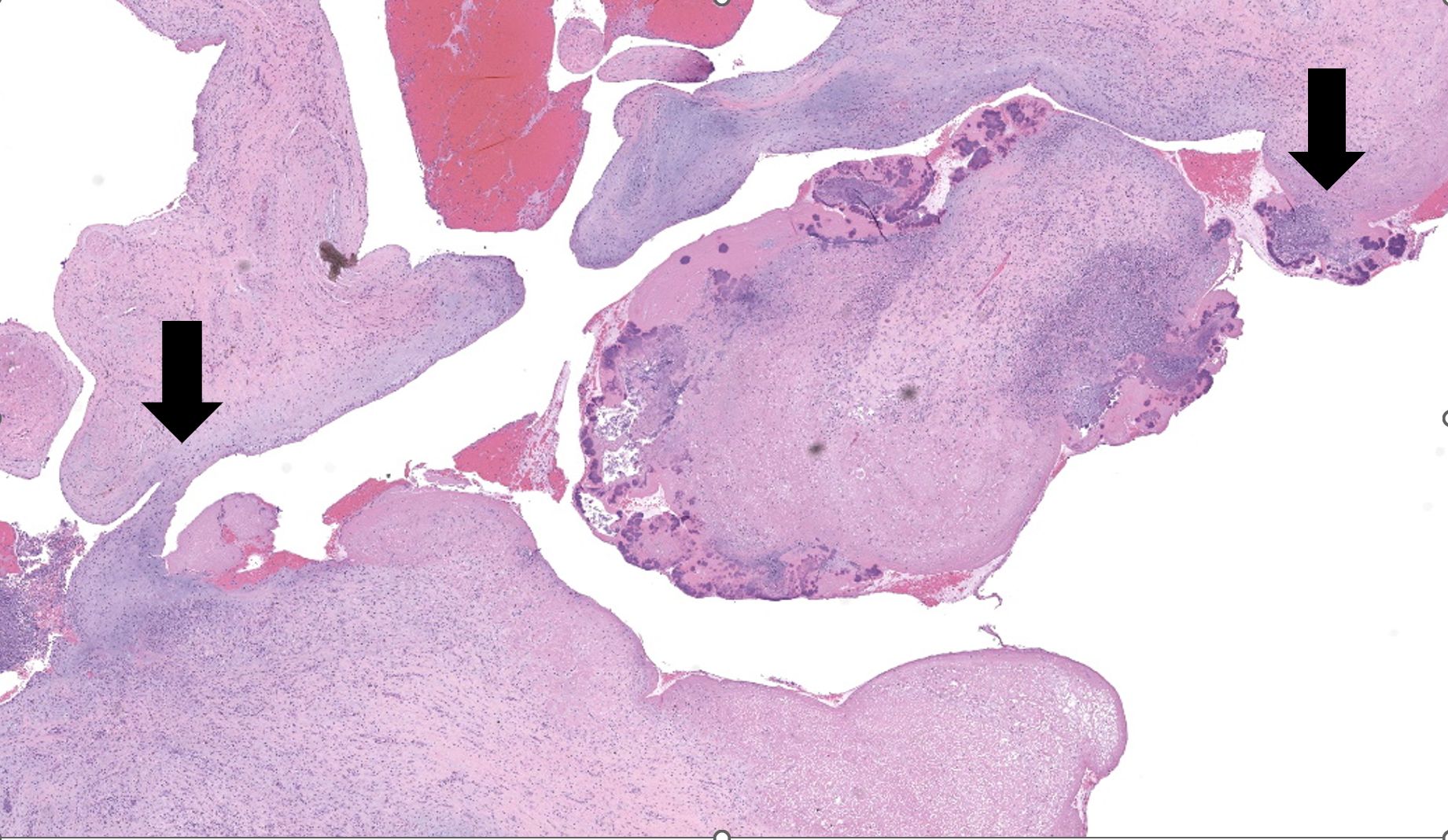

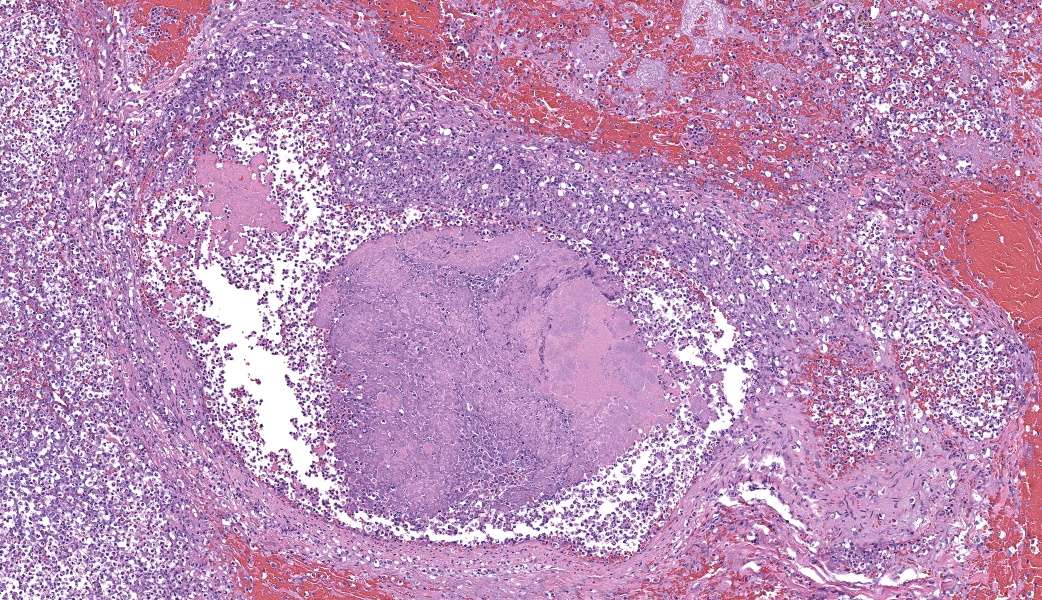

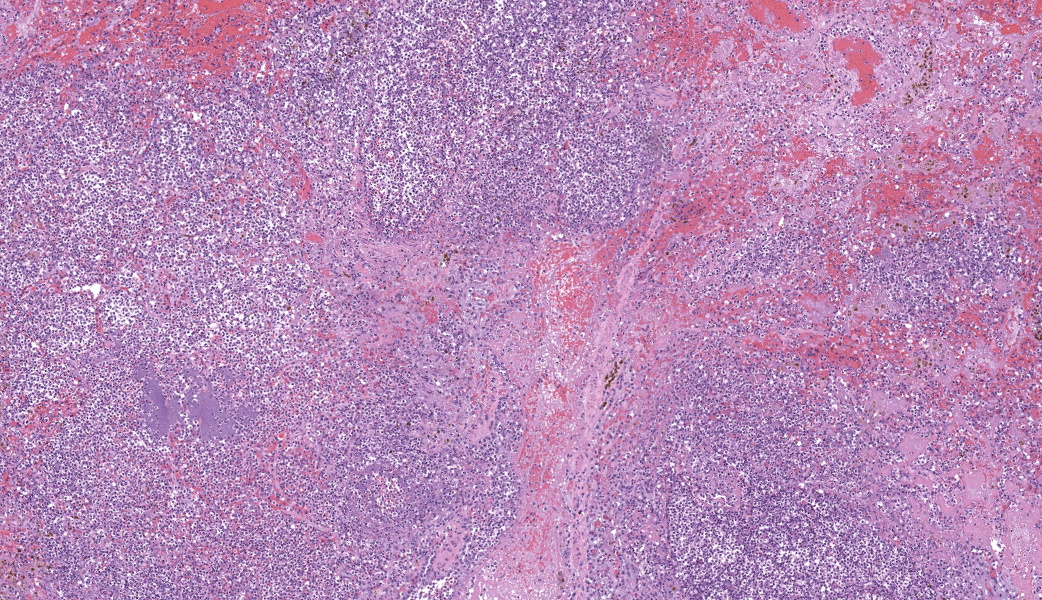

Representative sections of heart and lungs are examined.In the heart, the right atrioventricular valve is extensively overlain by large mats of fibrin, admixed with numerous degenerate and viable neutrophils and multiple coccobacilli bacterial colonies. The valvular stroma is diffusely expanded by moderate myxedema and there are moderate numbers of neutrophils and lesser numbers of hemosiderin-laden macrophages, plasma cells and lymphocytes scattered throughout the valvular stroma and expanding the endocardium of the adjacent papillary muscles. The epicardium and surrounding adipose tissue are mildly infiltrated by small numbers of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells.

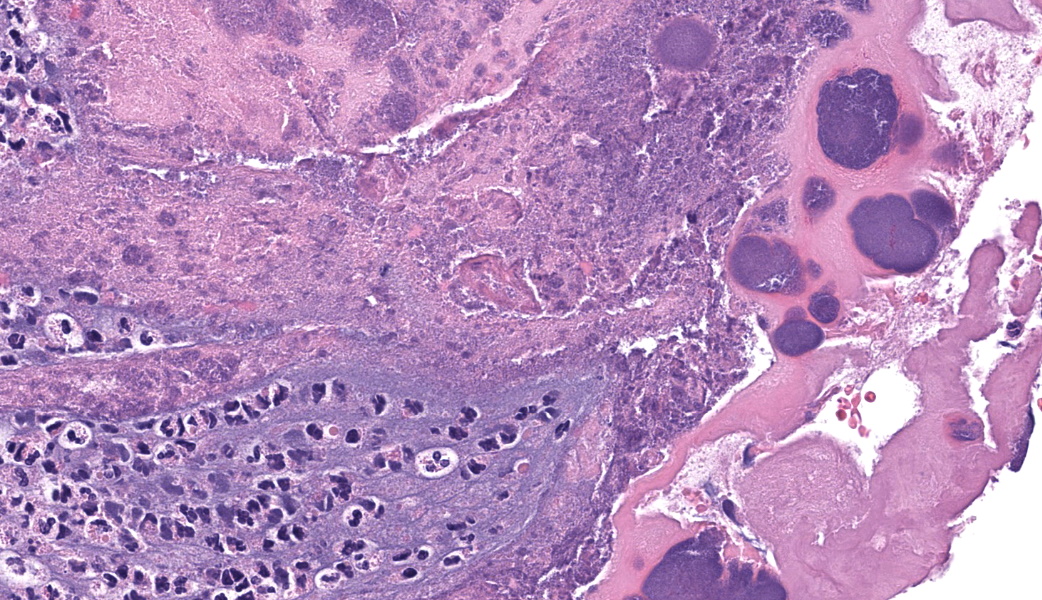

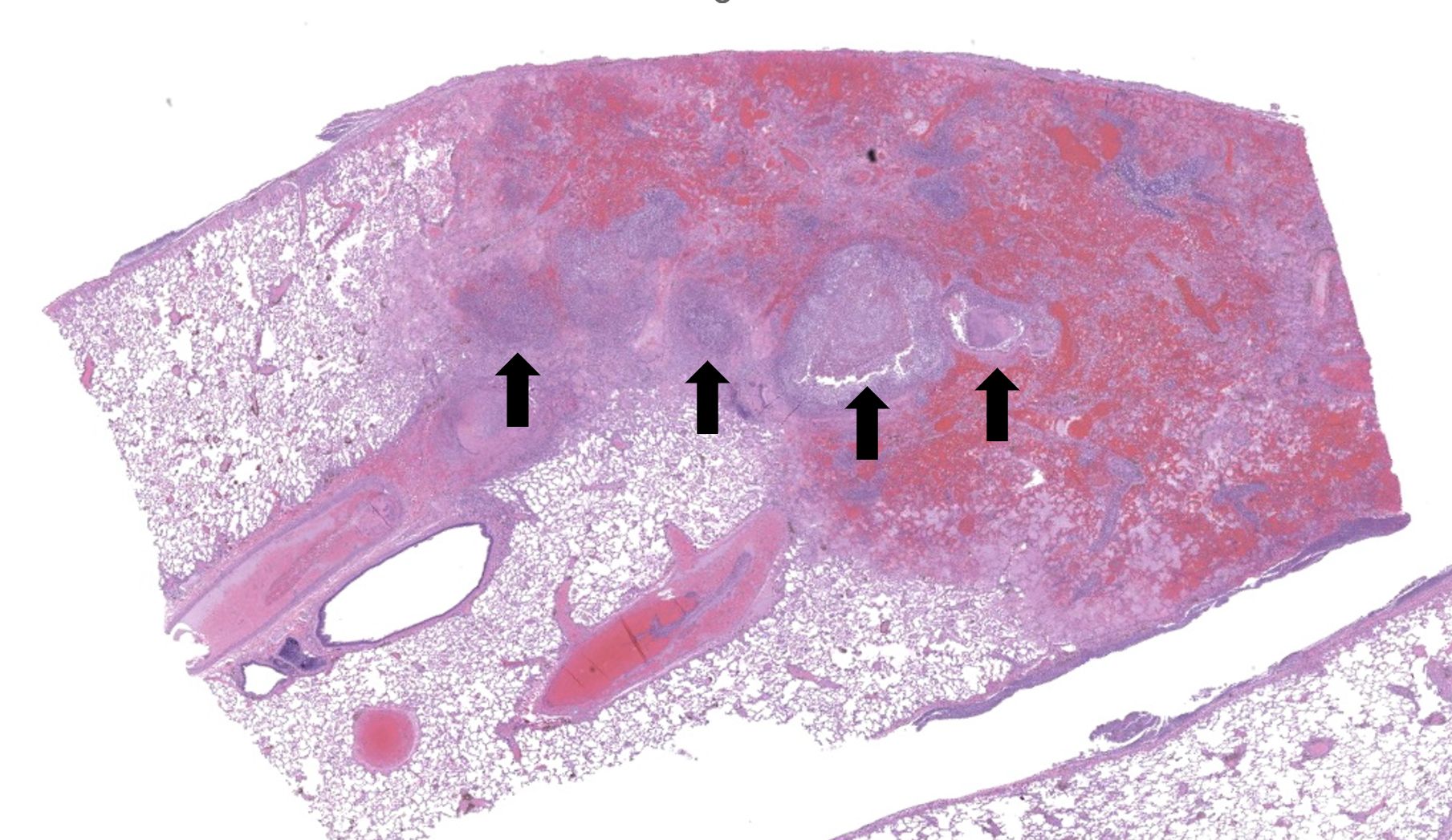

Regionally, sharply demarcated areas of the pulmonary parenchyma are markedly necrotic and replaced by abundant hemorrhage, fibrin, inflammatory infiltrates composed mainly of neutrophils and macrophages, and necrotic cellular debris. In these areas, multiple blood vessels contain thrombi consisting of large numbers of degenerate neutrophils, organizing fibrin, occasional colonies of bacterial coccobacilli, and necrotic cellular debris that variably obscure the lumen and vessel walls. Affected vessels often have smudgy, hypereosinophilic walls that are transmurally infiltrated by neutrophils, lymphocytes, and macrophages. In less affected regions, the alveolar spaces contain a small amount of fibrin, numerous foamy alveolar macrophages (some of which contain brown granular hemosiderin pigment), and fewer neutrophils and erythrocytes. There are moderate numbers of hemosiderin-laden macrophages mostly concentrated around pulmonary arteries, multifocally. Regionally, along the pleural surface there is a large amount of fibrin admixed with numerous degenerate neutrophils and necrotic cellular debris. The pleura itself is mildly thickened by fibrous connective tissue and edema and is multifocally lined by markedly reactive mesothelium, characterized by plump, rounded mesothelial cells.

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

Heart, right atrioventricular valve: Marked, chronic, fibrinosuppurative valvular endocarditis with intralesional bacterial colonies; Mild, multifocal, suppurative epicarditisLungs: Marked, regional, suppurative, necrotizing embolic pneumonia with vascular thrombosis and intrathrombotic bacteria; Marked, regional, fibrinosuppurative pleuritis

Contributor's Comment:

Endocarditis refers to the inflammation of the endocardium, primarily of the heart valves, and can affect most animal species.7 Mechanistically, endothelial lesions tend to start at areas of highest trauma, particularly the lines of apposition of the valvular surface exposed towards the direction of blood flow.2,5 Bloodborne microorganisms may become adhered to these regions, resulting in a localized infection, which can cause valvular injury and subsequent insufficiency.2,5 Infectious causes are usually of bacterial origin, usually from systemic infection, but can also be of mycotic or parasitic origin.5 The bacteria most commonly involved in valvular endocarditis varies among species, but Streptococcus sp., Staphylococcus sp., and Enterococcus sp. have been implicated in endocarditis in humans and most animal species.5 In cattle, Trueperella pyogenes is the most common agent involved in bacterial endocarditis, whereas in pigs, Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae is most common. Bacterial endocarditis is less common in horses, dogs, and cats.5Valvular endocarditis usually involves the left atrioventricular valve, followed by the aortic valve, right atrioventricular valve, and pulmonic valve.5 In non-human primates, valvular endocarditis is an uncommon spontaneous finding, with an incidence of 0.6% of all spontaneous cardiovascular lesions observed.1 Endocarditis can be associated with systemic bacterial infections or, particularly in the laboratory environment, contaminated venous indwelling catheters, the latter more commonly affecting the right atrioventricular valve.6 Interestingly, in cattle, the right atrioventricular valve is mostly affected, most likely due to the increased incidence of liver abscesses and subsequent bacterial venous spread to the caudal vena cava and right side of the heart.4

As the adherence of bacteria and blood components to the valve leaflets progresses, irregular, raised vegetations replace the smooth valvular surface.5 Portions of such vegetations may become detached and travel throughout the body as septic emboli.5 Emboli arising from the right side mainly affects the lungs, while emboli from the left side may dislocate and travel to distant organs, such as kidney and spleen.5

In the current case, right-sided valvular endocarditis was observed, most likely a consequence of a contaminated venous injection. Septic emboli translocated to the lungs, causing pulmonary thrombosis and infarction. Bacterial cultures of the heart and lungs revealed large numbers of E. coli and fewer Staphylococcus sp.

Contributing Institution:

Charles River Laboratories Mattawan (criver.com/products-services/safety-assessment/preclinical-facilites/Mattawan-michigan)JPC Diagnoses:

1. Heart, right AV valve: Valvulitis, fibrinosuppurative, chronic, focally extensive, severe, with valvular remodeling and numerous colonies of coccobacilli.

2. Lung: Pneumonia, embolic, necrotizing and suppurative, chronic, multifocal to coalescing, severe, with septic arterial thrombi and suppurative pleuritis.

JPC Comment:

This second case provides a beautiful example of an infective endocarditis with subsequent embolic bacterial pneumonia, stimulating value-added educational discussion of a classic pathogenesis that the contributor sums up nicely in their comment. Other major points of discussion included clinical signs associated with either right or left-sided emboli and associated gross lesions with endocarditis, including those seen in acute cases where only irregular ulcerations on swollen valve leaflets may be seen instead of the more classic irregular “vegetations” on affected valves.Conference participants were again asked to recall the “YAACSS-NT” acronym of large colony-forming bacteria, which was previously spelled out in this year’s Conference 3, if a refresher is needed. (Repetition is key!) To drive home the dramatic degree of valvular expansion seen in the heart in this case, a review of valvular anatomy followed and included discussion of the normal composition of valves, which are made up of collagen, ground substance (proteoglycans and elastin fibers), and endothelium lining both sides of the valve leaflets.

Endocarditis was first documented almost 350 years ago.3 The term “vegetative” in the term “vegetative valvular endocarditis” refers to the clumps of bacteria, fibrin, platelets, and other cellular material that adhere to a damaged heart valve. This conglomeration has traditionally been referred to as a “vegetation”. This term was first used by French physician Jean-Nicolas Corvisart in 1806 to describe “wart-like growths” he observed on the heart valves of patients with endocarditis at autopsy, stating that they appeared to resemble natural plant life.3 Considering this information, one must wonder of Dr. Corvisart had, in fact, ever seen a plant in his own natural life to have named it thus. Despite its historical use, the medical community as a whole is has moved away from that term in favor of either “infective endocarditis” when microorganisms are present, or “nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis” when the lesion is sterile.

References:

- Chamanza R, Parry NM, Rogerson P, Nicol JR, Bradley AE. Spontaneous lesions of the cardiovascular system in purpose-bred laboratory nonhuman primates. Toxicol Pathol. 2006;34:357-363.

- Chorianopoulos E, Bea F, Katus HA, Frey N. The role of endothelial cell biology in endocarditis. Cell Tissue Res. 2009;335:153-163.

- Geller SA. Infective endocarditis: a history of the development of its understanding. Autops Case Rep. 2013;3(4):5-12.

- Gudmundson J, Radostits OM, Doige CE. Pulmonary thromboembolism in cattle due to thrombosis of the posterior vena cava associated with hepatic abscessation. Can Vet J. 1978;19:304-309.

- Robinson WF, Robinson NA. Chapter 1 - Cardiovascular System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy & Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals: Volume 3 (Sixth Edition). B. Saunders; 2016:1-101.e101.

- Saravanan C, Flandre T, Hodo CL, et al. Research Relevant Conditions and Pathology in Nonhuman Primates. ILAR Journal. 2020;61:139-166.

- Vilcant V, Hai O. Bacterial EndocarditisStatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL);2023.