Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 14

January 10th, 2018

CASE II: 2 (salmon colored slide) (JPC 4101493).

Signalment: 6-year-old, female, Epagneul Breton (French Brittany), Canis familiaris, canine.

History: The dog was found dead at home 23 days after parturition. The owner reported that delivery was normal and the dog gave birth to three puppies.

Gross Pathology: At the necropsy, the dog was emaciated and moderate hemorrhagic enteritis and diffuse pulmonary edema were observed. The endometrium was hemorrhagic and thickened by the presence of brown ellipsoidal enlargements (previous placental attachment) distributed in the left and right uterine horns. The uterine lumen contained small amounts of serosanguinous fluid. The cause of death was attributed to development of acute pneumonia.

Laboratory results:

None provided.

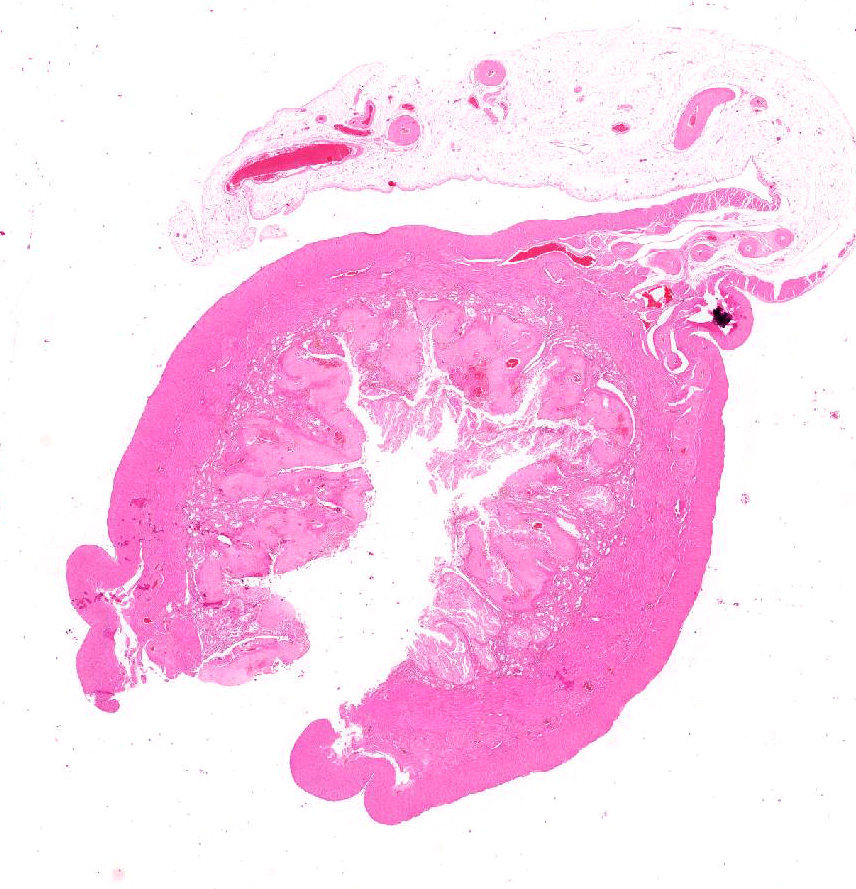

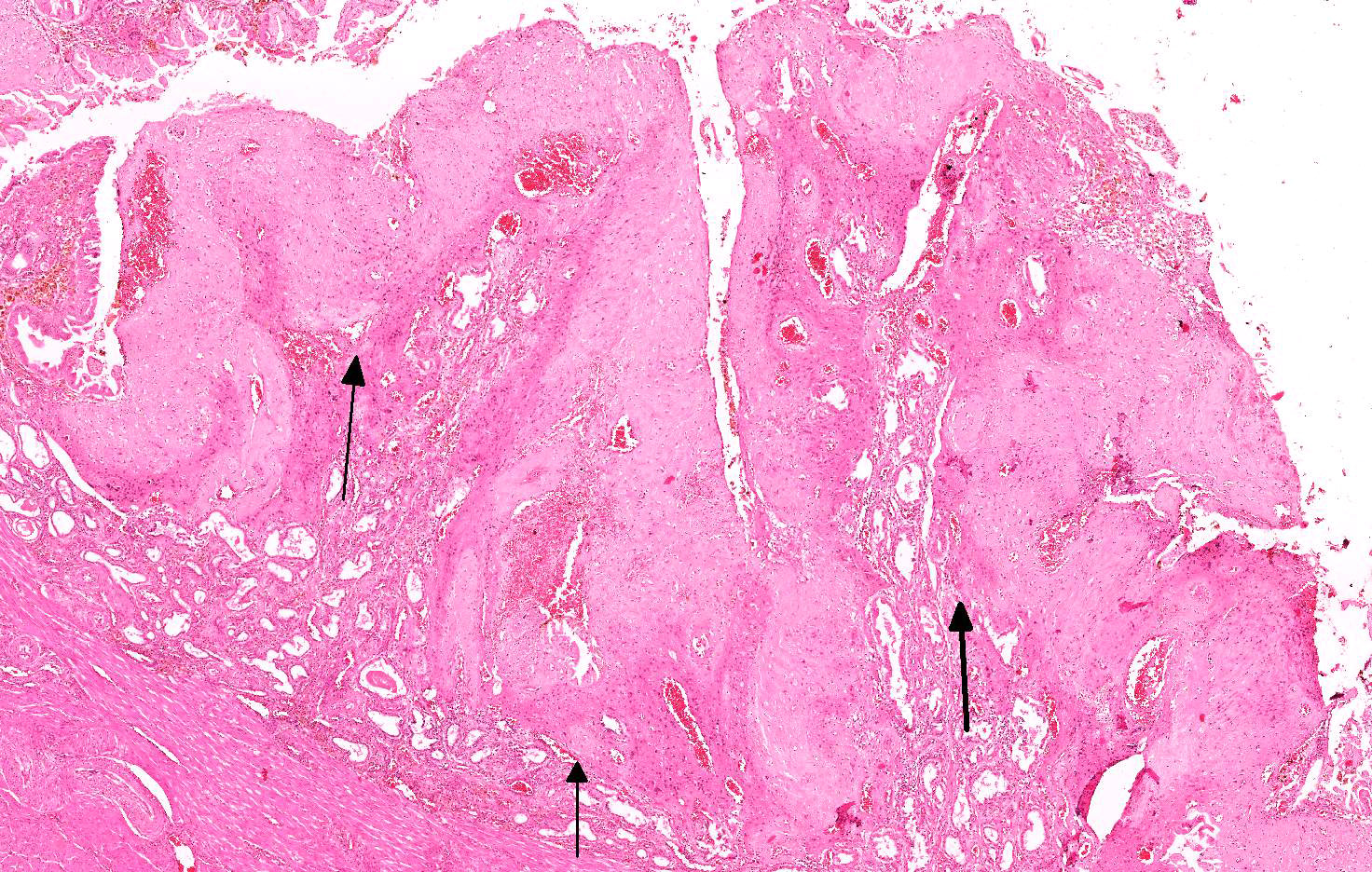

Microscopic Description: Uterus, placental sites: The uterine mucosa is expanded by irregular, multilobulated, eosinophilic projections that compress the adjacent endometrium.

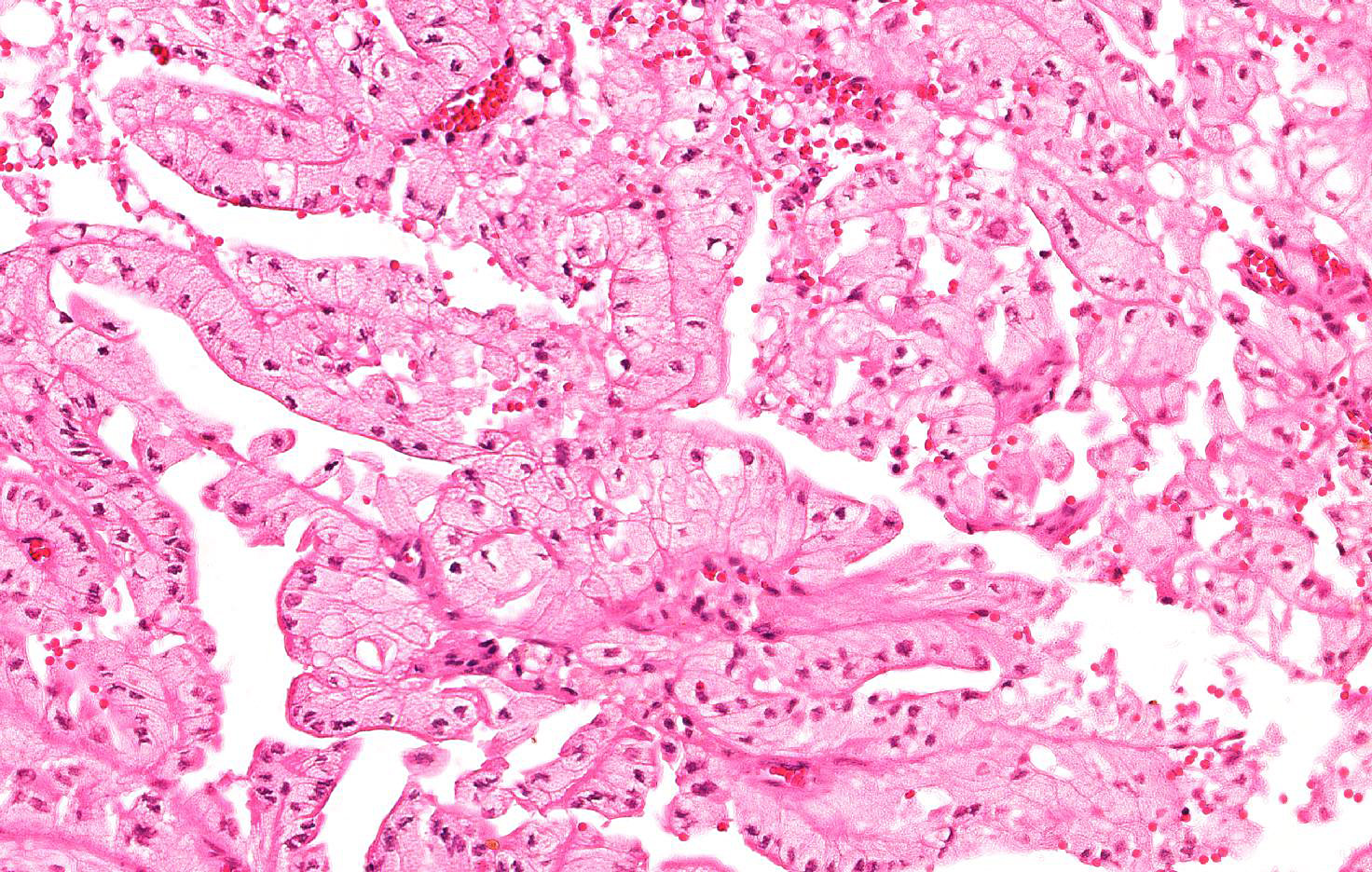

The mass is composed by large amount of fibrillary pale eosinophilic dense material (collagen), finely beaded meshwork of fibrillary, pale eosinophilic material (fibrin), moderate amount of extravasated erythrocytes (hemorrhage), and necrotic and karyorrhectic debris accumulating prevalently in the proximal 1/3rd the projections. Between the deepest portion of the eosinophilc matrix and the glandular zone, there are variable numbers of polygonal multinucleated giant cells with an epithelioid appearance characterized by abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm, often vacuolated (decidual cells/syncytial trophoblast). These cells were often oriented around vascular structures that were characterized by hyaline walls (vascular degeneration). The glandular zone is characterized by reduced number of endometrial glands, that are multifocally variably dilated and filled with moderate amount of eosinophilic fluid and necrotic and karyorrhectic debris. Within the endometrial mucosa, lamina propria is fibrotic and moderate numbers of mature lymphocytes, plasma cells, and lesser numbers of hemosiderin laden macrophages were also present (mild chronic endometritis). Multifocally, the superficial mucosa lining is sloughed, but when present is organized in papillary projections lined by swollen columnar epithelial cells with abundant, clear, foamy vacuolated cytoplasm and apically located vesicular nuclei (progestational epithelium).

Additional findings (not in the slides): numerous follicles and large corpora lutea were present both ovaries.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Uterus, placental site: Coagulative necrosis, subacute, locally extensive, moderate, with retention of trophoblasts/decidual cells, hemorrhages and mild chronic lymphoplasmacytic endometritis (involution of placental sites).

Contributor’s Comment: In dogs, normal involution of the genital tract, after whelping is a slower process compared to other species. More rapid initial involution occurs during the first 4-6 week post-partum. During this period odorless green or dark brown vaginal discharge called “lochia” can be observed (as it was for this dog).

Histologically, placental site involution starts with massive epithelial sloughing into the uterine lumen. Sloughing is at the level of attachment to the endometrial lamina propria that is also expanded by the presence of inflammatory cells (lymphocytes, plasma cells and macrophages).2 Trophoblasts, on the surface of the uterine mucosa and scattered throughout the lamina propria, are numerous, often necrotic and degenerated, and according to Orfanou et al.,7 can be observed even at 84 days post-partum. The area of detachment is soon regenerated and covered by a single layer of columnar epithelial cells. During involution, the majority of the uterine glands return to normal size and shape. By the commencement of the eighth week almost all of the collagen masses have sloughed into the lumen. This process continues until the end of the twelfth week and finally, the uterus can be classified as anestrus from the thirteenth week postpartum.2,7

Subinvolution of placental sites (SIPS) is a disorder of young, primiparous bitches that causes a sanguineous vulvar discharge any time after the fourth week postpartum. In bitches with SIPS, there is a failure or delay in normal uterine involution or a delay of fetal trophoblasts to regress physiologically.1,8

Usually, young bitches are affected, even if the exact etiology of the condition is unknown but factors thought to play a role include failure of thrombus formation and occlusion of endometrial blood vessels due the continuous invasion of trophoblast-like cells into the endometrium and myometrium and the decreased influence of decidual cells on them.1 SIPS has also been reported in women, and although placentation is hemochorial in humans (versus endotheliochorial in dogs), the pathogenesis of SIPS seems similar. In humans, it has been suggested that important factors in the pathogenesis of SIPS include poor interaction between extravillous cytotrophoblasts and maternal decidual tissue, the absence of immunoglobulins and complement proteins in subinvoluted vessels, and persistent expression of the anti-apoptosis protein Bcl-2, which prevents apoptosis and thereby promotes maintenance of utero-placental vessels.3,12

A consistent histological feature is retention and invasion of trophoblast like cells into the underlying stroma and even into the myometrium,1 together with the presence of abundant collagen mass, largely necrotic and hemorrhagic, that can extended down to involve the whole mucosa or even part of the myometrium. Moreover, the retained trophoblastic cells do not regress or degenerate, but continue to invade the deep glandular layer or even the myometrium, preventing normal thrombus formation in endometrial blood vessels6 and can be the reason for the prolonged duration of vulvar discharge observed clinically.

The timing of persistence of trophoblast-like cells in physiological involution and subinvolution of placental sites is debated. According to Al-Bassam and co-workers1 these cells would be present during the first 2 weeks postpartum but in the case of SIPS they persist for a longer period of time. A recent study however, shows that these cells persist on the surface of the uterine epithelium, the placental tissues, as well as in smears of vulvar discharge during the whole period of involution even up to 84 days postpartum in normal involution of the uterus in the bitch.7

Clinically, a chronic post-parturient serous or sanguineous discharge (4 to 16 weeks after parturition or even until the beginning of the next estrous) without any systemic illness is the most common presentation.6 Affected animals can become anemic, and the uterus is prone to ascending infections.

Spontaneous regression of normal placental sites usually occurs in bitches in good health without significant anemia.9 However, dogs should be closely monitored weekly or biweekly with clinical, hematologic and ultrasonographic examinations because of the risk of uterine perforation and peritonitis, albeit rare.6

In cases of severe bleeding, blood transfusions and ovariohysterectomy should be immediately considered. Usually the affected bitches are not predisposed to recurrence of the disorder as this is a condition that only affects primiparous bitches.11

JPC Diagnosis: Uterus, placental site: Normal placental site involution, Epagneul Breton (French Brittany), canine.

Conference Comment: This case accentuates the importance of a good clinical history. Subinvolution of placental sites (SIPS) looks histologically identical to normal involution.

SIPS occurs in young, primiparous bitches and is characterized clinically by prolonged blood-tinged vaginal discharge due to failure of trophoblasts to regress postpartum resulting in delayed re-epithelialization of the endometrium. Sources vary as to duration postpartum that normal uterine bleeding ceases, some say past 7-10 days10 and others 1-6 weeks5, and placental sites should be involuted by the 12th week. Nevertheless, the clinical and microscopic manifestations are diagnostic for this syndrome which currently has an unknown cause.5 Grossly, the uterine horns (cornua) contain segmental, ellipsoidal, irregular, grey to brown thickenings in areas where the placenta previously attached. The adjacent endometrium is normal grossly and microscopically. Microscopically, these thickenings are composed of a combination of amorphous eosinophilic matrix, fibrin, degenerating placental tissue, and regenerating endometrium.5 Trophoblasts are more numerous than in normal involuting placental sites and are often aggregated at the base of the fibrous masses and extend into the myometrium even penetrating the serosa and allowing leakage of uterine contents into the peritoneum. The overlying surface epithelium often has a heavily vacuolated cytoplasm indicating the influence of progesterone. Corpora lutea are consistently present in the ovary but progesterone levels are low.10 Sequella to SIPS are ascending infections, open pyometras, and endometritis. Additionally, in dogs with pre-existing bleeding disorders, like von Willebrand’s disease, rapid exsanguination is a gruesome reality.5

The composition of the large pink masses largely replacing endometrial tissue within the involuting uterus was a subject of spirited discussion, with some favoring a necrotic coagulum and others favoring a collagenous plaque. In truth, the correct answer is a combination of both. During involution, at approximately 2-3 weeks large plaques of collagen are formed in the involuting endometrium; these plaques are generally sloughed around 8 weeks.1 this is consistent with the clinical history in this case of a uterus at 23 days post-partum.

Hamsters and other rodents (see below) have a labryrinthine hemochorial placenta in which the trophoblast cells are in direct contact with the maternal vasculature. Therefore, they routinely have giant trophoblastic cells in the myometrial arteries (they have tropism for arterial blood) and rarely in the pulmonary arteries during gestation and up to 3 weeks postpartum.4

Table 1: Placental types by species4,5,10

|

Species |

Distribution of contact |

Classification by maternal cell layers |

Maternal-fetal interdigitation |

|

Mare, Sow |

Diffuse |

Epitheliochorial |

Villi (horse: “cups”, pig: folded villi) |

|

Ruminant |

Cotyledonary |

(Syn)epitheliochorial (combination) |

Villi |

|

Bitch, Queen |

Zonary |

Endotheliochorial |

Labyrinth |

|

Rhesus macaque |

Double discoid |

Hemochorial |

Villi |

|

Ape, human |

Discoid |

Hemochorial |

Villi |

|

Rabbits, rodents |

Discoid |

Hemochorial |

Labyrinth |

Contributing Institution:

DIMEVET –Anatomical Pathology Section

Faculty of Veterinary Medicine of Milan, Italy

http://www.dimevet.unimi.it/ecm/home

References:

- Al-Bassam MA, Thomson RG and O’Donnell L. Involution abnormalities in the postpartum uterus of the bitch. Veterinary Pathology. 1981;18:208–216.

- Al-Bassam MA, Thomson RG and O’Donnell L. Normal postpartum involution of the uterus in the dog. Canadian Journal of Comparative Medicine. 1981;45:217–232.

- Andrew A, Bulmer JN, Morrison L, Wells M, Buckley CH. Subinvolution of the uteroplacental arteries: an immunohistochemical study. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 1993;12:28–33.

- Barthold SW, Griffey SM, Percy DH. Hamster. In: Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits. 4th Ames, IA: Wiley Blackwell; 2016:174.

- Foster RA. Female reproductive system and mammae. In: Zachary JF, ed. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 6th St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:1189.

- Johnston SD, Kustritz MVR and Olson PNS. Subinvolution of placental sites. In: Johnston SD, Kustritz MVR, Olson PNS, eds. Canine and Feline Theriogenology. 1st Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1991:139–141.

- Orfanou DC, Ververidis HN, Pourlis A, Fragkou IA, Kokoli AN, Boscos CM, Taitzoglou IA, Tzora A, Nerou CM, Athanasiou L, Fthenakis GC. Post-partum involution of the canine uterus – gross anatomical and histological features. Reproduction in Domestic Animals. 2009;44 (Suppl 2):152–155.

- Reberg SR, Peter AT, Blevins W. Subinvolution of placental sites in dogs. Compendium on Continuing Education for the Practicing Veterinarian. 1992;14:789–796.

- Schall WD, Duncan JR, Finco OR, Knecht CD. Spontaneous recovery after subinvolution of placental sites in a bitch. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 1971;159:1780–1782.

- Schlafer DH, Foster RA. Female genital system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. 3. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:441.

- Sontas HB, Stelletta C, Milani C, Mollo A, Romagnoli S. Full recovery of subinvolution of placental sites in an American Staffordshire terrier bitch. J Small Anim Pract. 2011;52:42-45.

- Weydert JA, Benda JA. Subinvolution of the placental site as an anatomic cause of postpartum uterine bleeding: a review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2006;130:1538–1542.