Wednesday Slide Conference, Conference 18, Case 1

Signalment:

Young adult female wild pigeon (rock dove, Columba livia).

History:

The pigeon was found dead with no known history. Necropsy was performed as part of a wildlife disease screening program.

Gross Pathology:

Gross examination identified moderately thin body condition and mild pallor of the spleen.

Laboratory Results:

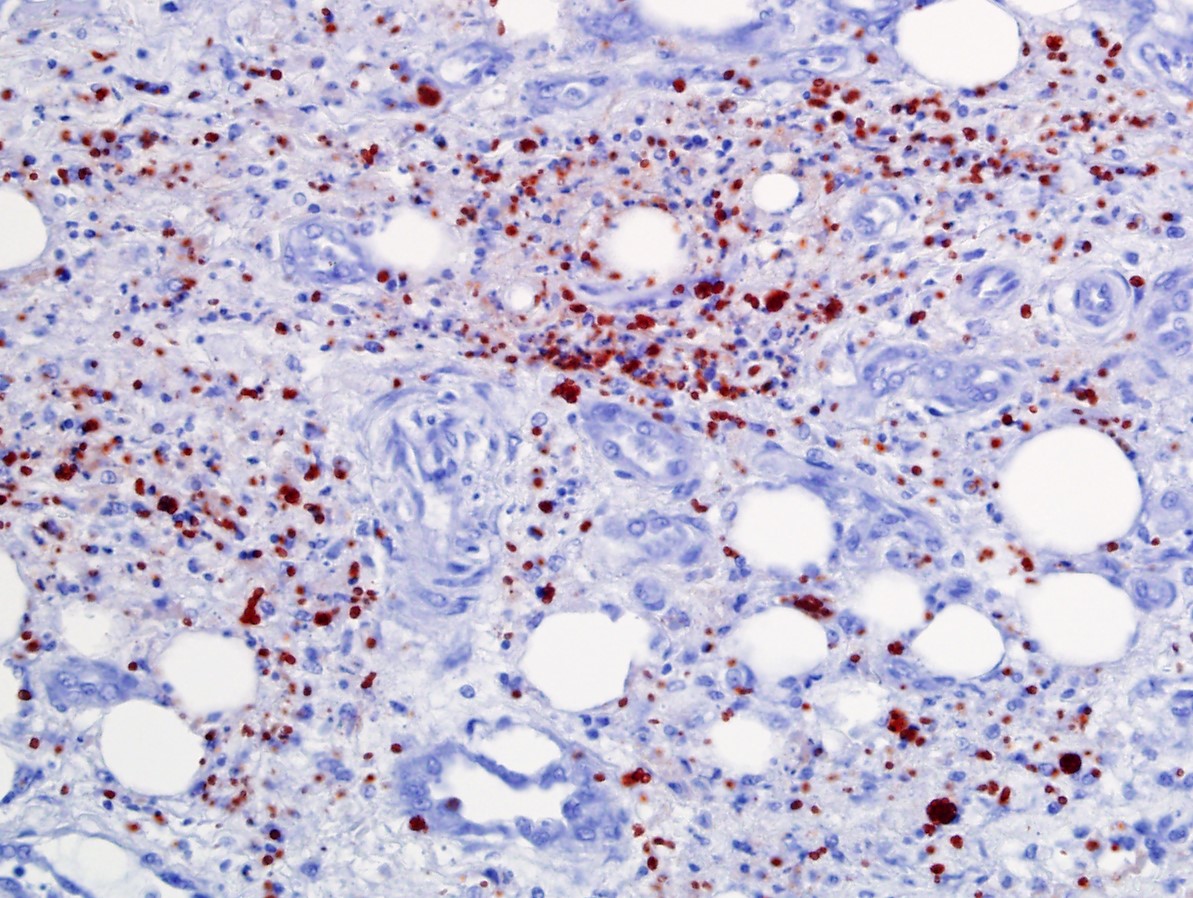

Immunohistochemistry for Toxoplasma gondii and Sarcocystis sp. showed strong positive immunolabeling of abundant intralesional zoites for T. gondii in multiple tissues (e.g., liver, lung, cloaca, brain) and no immunolabeling for Sarcocystis sp.

A pan-Apicomplexan PCR (18s rDNA) and sequencing of the amplicon confirmed a sequence with 100% identity to several isolates of Toxoplasma gondii in Genbank.

Microscopic Description:

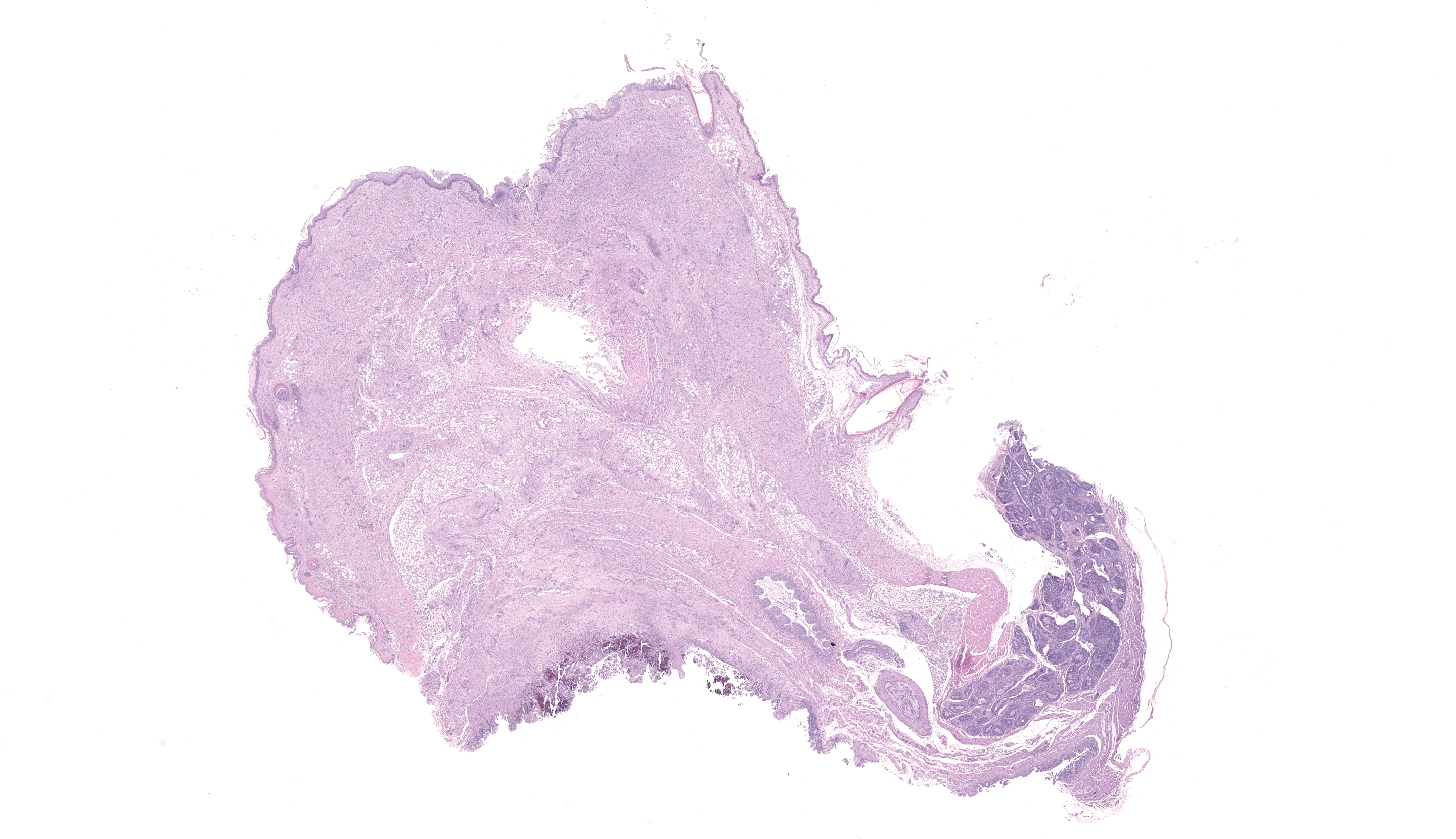

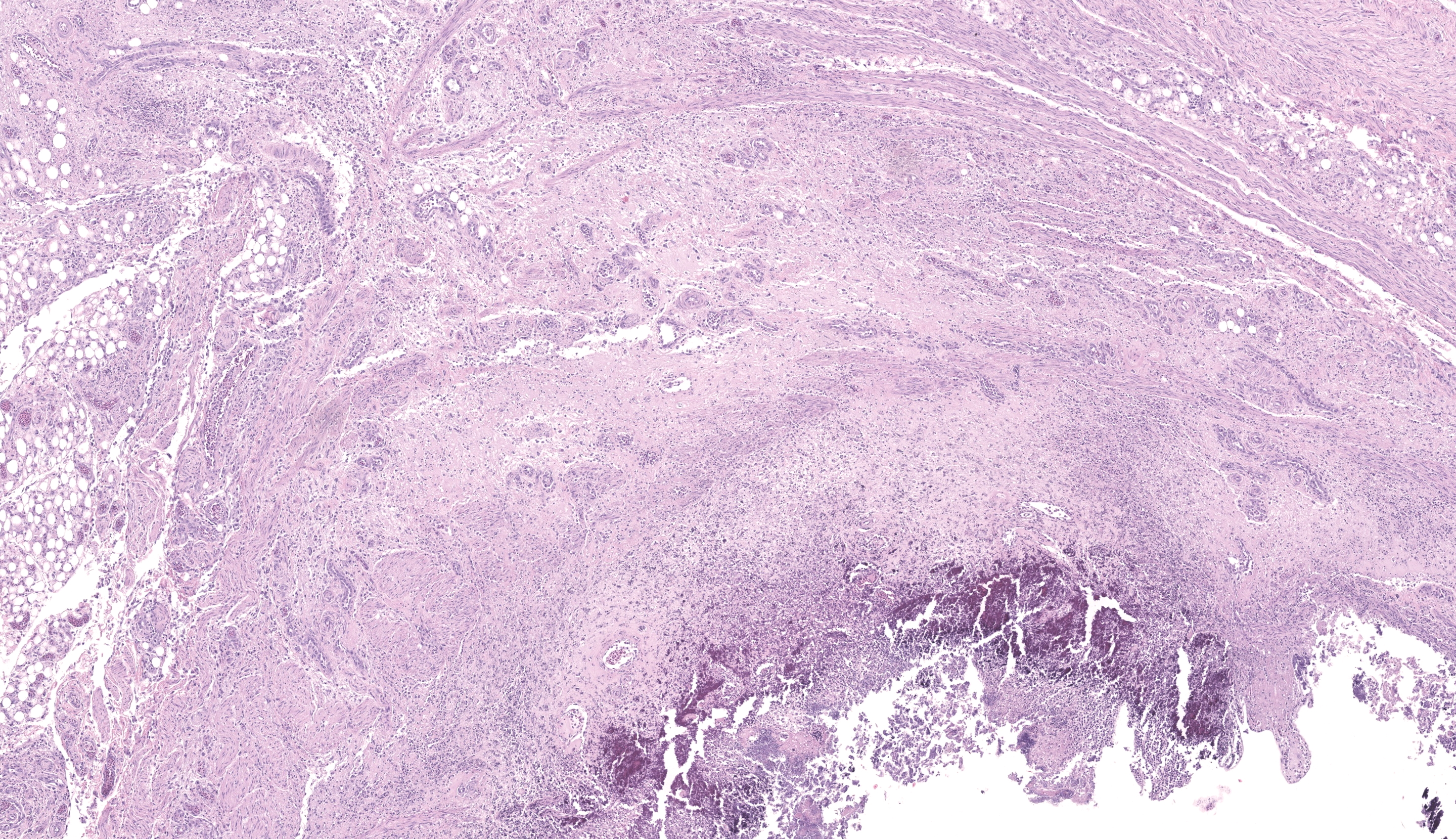

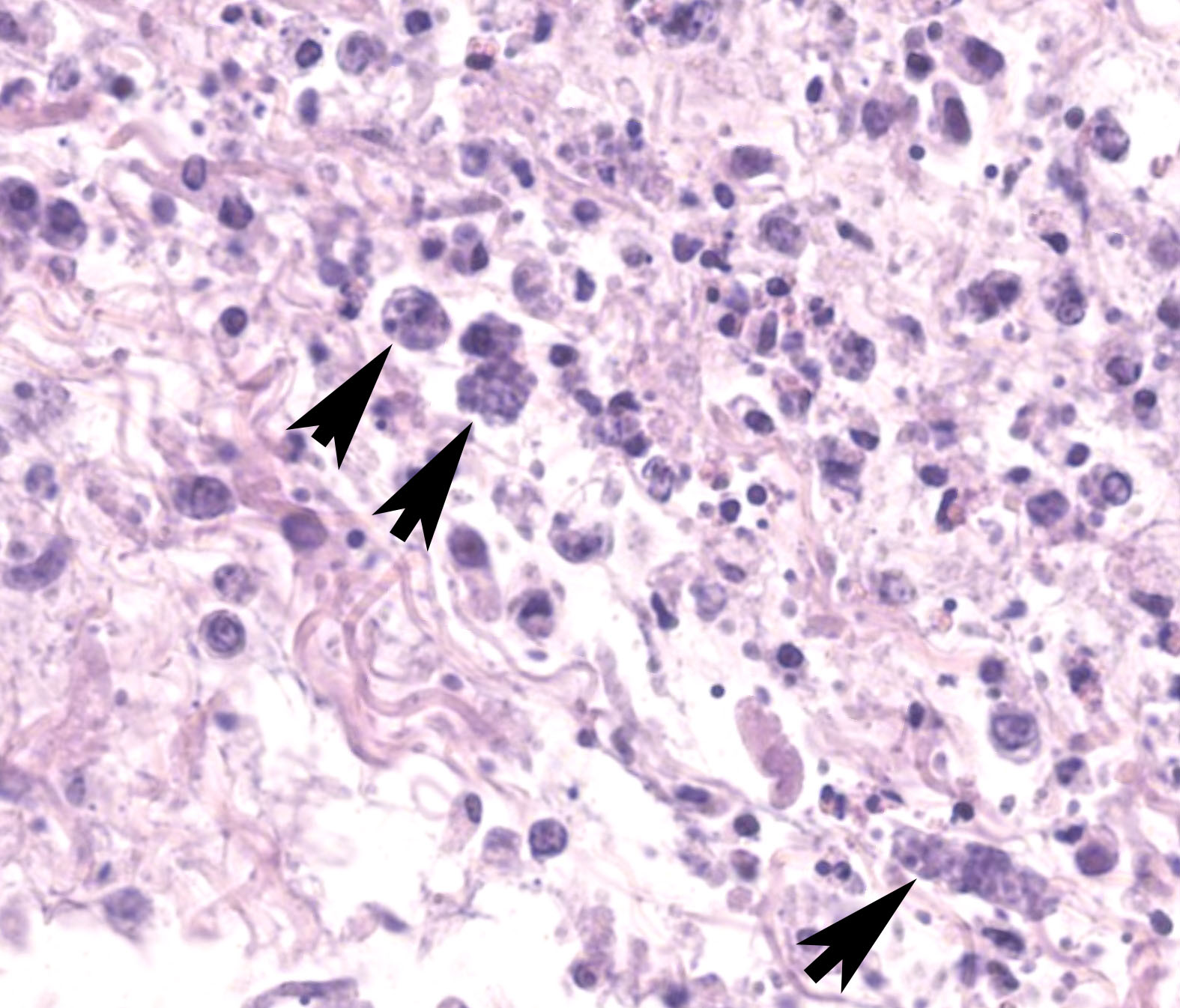

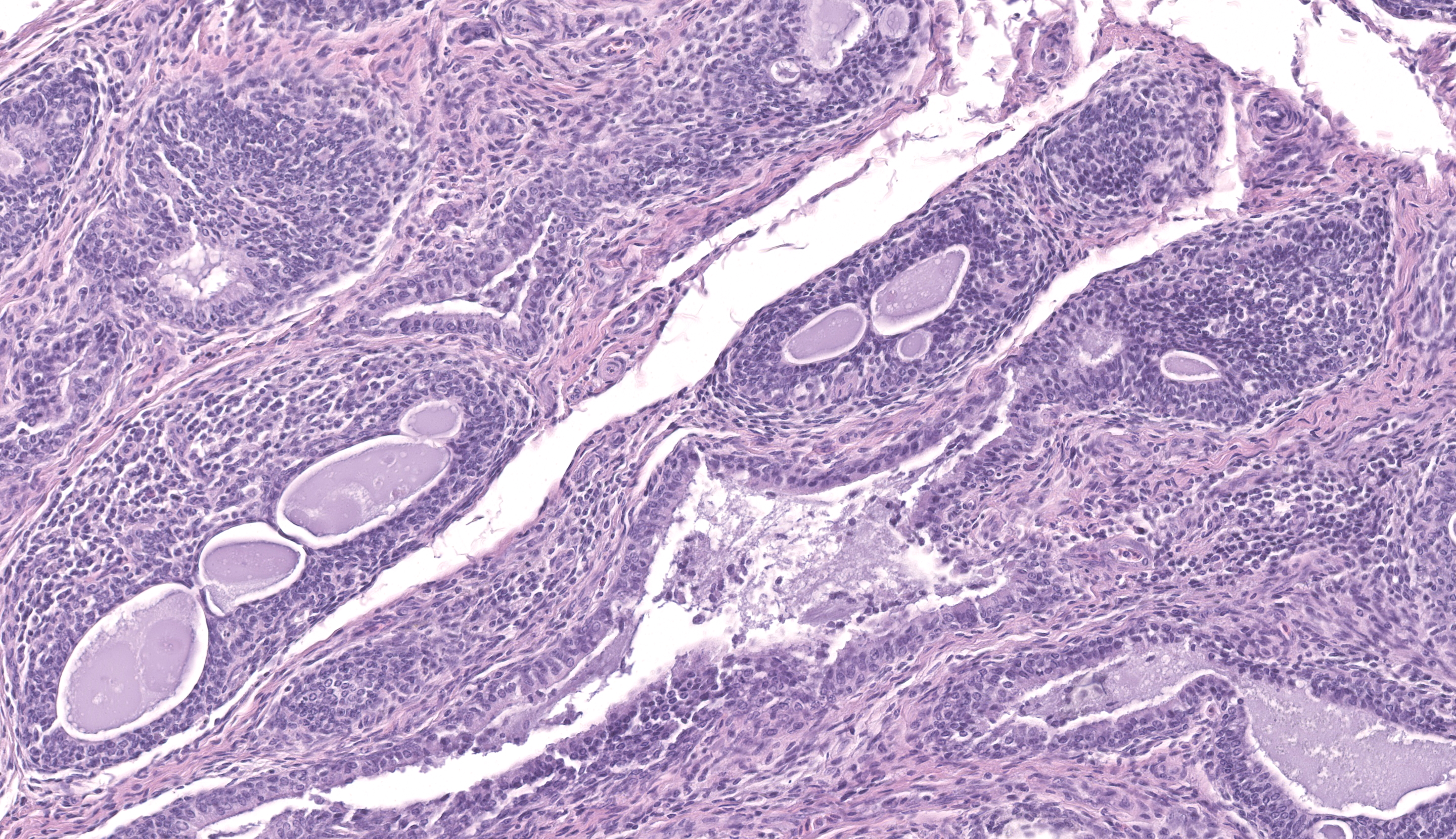

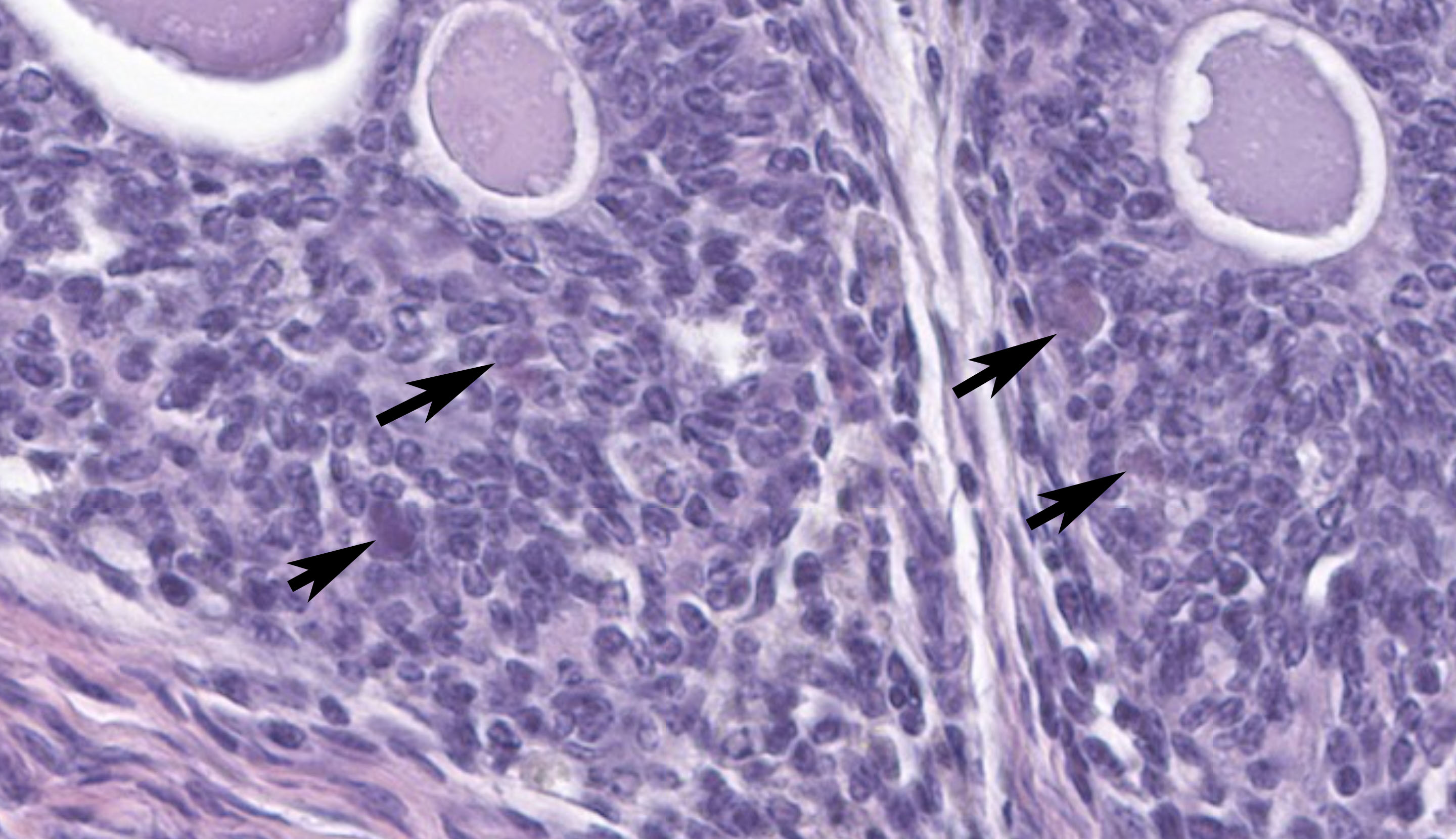

The sections of cloaca include variable proportions of cloacal mucosa, oviduct, pericloacal skeletal muscle, subcutis, skin, and adjacent Bursa of Fabricius. There is marked, diffuse, necrotizing cloacitis and pericloacal cellulitis (panniculitis, myositis, dermatitis). Moderate numbers of inflammatory cells, abundant admixed pyknotic and karyorrhectic cell debris (necrosis), amorphous eosinophilic material (edema), and myriad protozoal zoites are present transmurally in the cloaca and throughout the pericloacal subcutis, skeletal muscle, and dermis. Inflammatory cells consist primarily of histiocytes with fewer heterophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells. Zoites (tachyzoites) are approximately 2-3 um diameter and variably oval to crescentic (banana-shaped) with a pinpoint central nucleus and pale basophilic cytoplasm; many are individualized and extracellular, and moderate numbers are intracellular and range from individual zoites to haphazardly-arranged clustered groups (schizonts) often containing 6-16 distinct zoites. The intracellular organisms are present in endothelial cells, presumed histiocytes, fibroblasts, and myofibers. Lymphatics and blood vessels throughout the affected region are lined by hypertrophied endothelium (reactive), or are occasionally mildly thickened by intramural leukocytes or eosinophilic debris (vasculitis). The cloacal mucosa is variably moderately to markedly eroded to ulcerated, mineralized (dystrophic), and multifocally bordered by mixed bacteria along the denuded luminal surface. Skeletal myofibers are multifocally moderately fragmented, hypereosinophilic with loss of cross striations, and mineralized. The pericloacal epidermis is multifocally, variably, mildly to moderately hyperplastic, inflamed, and eroded, with intraepidermal leukocytes (heterophils, histiocytes, lymphocytes), intra- and inter-cellular swelling (edema), multifocal keratinocyte apoptosis and separation, and mild superficial dermal mineralization and pigmentary incontinence. Along the skin surface are mild segments of superficial orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis, and mild scattered loose mixed bacteria, occasional budding yeast, and debris (environmental). (A focal artefactual rent into the skin/subcutis is present in some levels).

The Bursa of Fabricius is atrophied with moderate to marked lymphocyte depletion, relative prominence of interstitial stroma, and multifocal dilated intrafollicular spaces containing basophilic fluid and occasional stippled basophilic material (mineral). Low numbers of cells (presumed histiocytes and Bursal epithelial cells) contain botryoid amphophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions (consistent with circoviral inclusions).

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

1. Cloaca and pericloacal tissue (skeletal muscle, subcutis, skin), Cloacitis and pericloacitis, necrotizing, histiocytic, diffuse, acute to subacute, moderate to marked, with abundant intralesional extra- and intra-cellular protozoal tachyzoites and schizonts, regional cloacal mucosal ulceration, multifocal vasculitis, edema, and mineralization

2. Bursa of Fabricius, Lymphoid depletion (follicle atrophy), chronic, diffuse, moderate to marked with scattered intracellular intracytoplasmic botryoid circoviral inclusions

Contributor’s Comment:

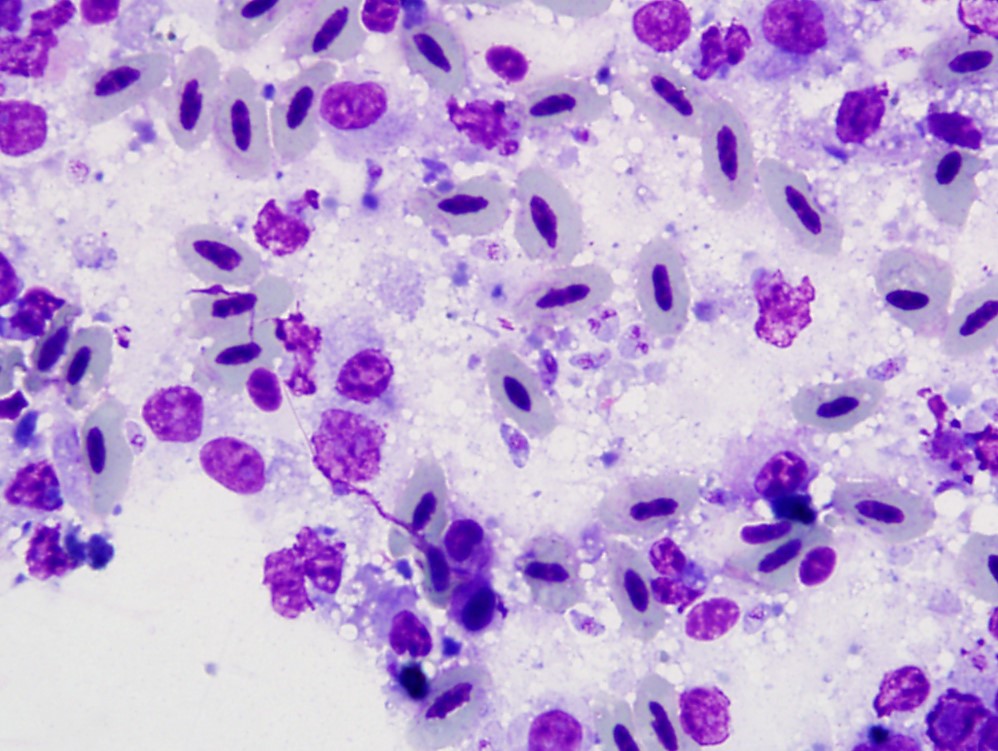

Protozoal infection consistent with toxoplasmosis was initially identified by cytologic examination of organ imprints (lung, spleen, and liver) obtained during necropsy. Histologic examination confirmed disseminated protozoal infection with prominent zoite-induced necrotizing hepatitis, pneumonia, and encephalitis amongst other lesions. Infection by Toxoplasma gondii (toxoplasmosis) was confirmed by immunohistochemistry and PCR. The cloacal tissue section demonstrated notably florid ‘cutaneous’ toxoplasmosis in addition to circoviral inclusions captured within the adjacent segment of Bursa of Fabricius, a not unexpected finding in wild pigeons and possible contributory factor for the extent of disease in this case.

Toxoplasmosis is a common obligate intracellular, apicomplexan, coccidian, protozoal infection affecting warm-blooded animals worldwide, including domestic and wild birds. Clinical toxoplasmosis has been reported in a variety of columbiformes (pigeons, doves), including individual and epizootic cases.4 Pigeons have shown high sensitivity to natural and experimental infection with high morbidity and mortality,3 and cases of natural infections are reported in a wide range of domestic and non-domestic pigeon species. Whereas the intermediate hosts of T. gondii infection are diverse, only felids are known to serve as definitive hosts for the sexual (coccidian) life stage. Major routes of intermediate and definitive host infection, respectively, are ingestion of infective oocysts, and predation of intermediate hosts by felids.

Reported clinical signs in birds include anorexia, weakness, emaciation, ocular signs (e.g., conjunctivitis, blepharitis, and exudate), dyspnea, and neurologic signs. Protozoal stages are found in many tissues, often including spleen, lung, and brain. In canaries (passeriformes) blindness has been reported as a unique but repeatable clinical presentation of natural infections, with intraocular and/or encephalitic toxoplasmosis seen histologically.4,11

Regardless of infected species, typical lesions of active toxoplasmosis consist of necrotizing inflammation with intralesional protozoal organisms. As in this case, the zoites and, less frequently, schizonts can be identified on cytologic tissue impression smears as individualized or clustered, extracellular or intracellular, oval to crescent-shaped pale basophilic organisms with a small nucleus and pale basophilic cytoplasm. Histology with immunohistochemistry and/or molecular testing are commonly employed for definitive diagnosis. Historically, bioassays of infected tissue homogenized and administered into mice were common.

Another apicomplexan infection, Sarcocystosis, was considered the primarily differential diagnosis in this case, but was excluded by ancillary testing (i.e. PCR and IHC). Other differentiating features of Toxoplasma gondii and Sarcocystis sp. include: predominant forms of schizogony (endodyogeny for T. gondii, in which two zoites are produced, and endopolygeny for Sarcocystis sp., in which four or more zoites are produced and can be seen as a radial rosette arrangement); and ultrastructure (in which Sarcocystis sp. lack rhoptries, excretory organelles, that are present in T. gondii).4 Although Neospora caninum is a classic differential for T. gondii cytologically and histologically, N. caninum is not known to infect birds. Systemic isosporosis (atoxoplasmosis) is another systemic coccidian infection of birds, but is morphologically distinct and was not a major differential in this case.

The heavy toxoplasmal dermatitis, panniculitis, and myositis around the cloaca in this case prompted a review of cutaneous toxoplasmosis which has been described in humans, few cats, and in rare cases, dogs. This infection can variably present as single localized, or up to many generalized, ulcerative, pustular, or nodular lesions, with or without pruritis. The lesions are histologically characterized by necrotizing and granulomatous or pyogranulomatous dermatitis, panniculitis, and vasculitis with extra-cellular or intra-cellular tachyzoites inhabiting a variety of cell types (e.g., macrophages, fibroblasts, glandular epithelium, and endothelium).2,6,8 Organism numbers can vary and parasite identification is reported as histologically challenging in some cases.6 Immunosuppression from concomitant illness and/or therapy (e.g., treatment for immune-mediate disease or transplantation) is a common predisposing factor.6,8,10

Basophilic botryoid cytoplasmic inclusions typical of circovirus were identified within the Bursa of Fabricius in this case. Pigeon circovirus is an incompletely described infection of young birds linked to acquired immunosuppression due to lymphocytic depletion in primary and secondary lymphoid tissues. It has been associated with propensity for a variety of secondary infections.1,13 Circoviral infection has been linked to Young Pigeon Disease Syndrome (Young Bird Syndrome, Swollen Gut Syndrome) in racing and fancy pigeons in parts of Europe.7 Immunosuppression was a possible contributing factor to the occurrence and severity of toxoplasmosis in this case.

Contributing Institution:

Wildlife Conservation Society

www.wcs.org

JPC Diagnosis:

1. Cloaca and pericloacal tissue (skeletal muscle, subcutis, skin): Cloacitis and pericloacitis, necrotizing, pleocellular, subacute, marked, with abundant zoites and schizonts

2. Bursa of Fabricius: Lymphoid depletion, chronic, diffuse, moderate, with cystic follicular ectasia and botryoid intracytoplasmic viral inclusions

JPC Comment:

This week’s moderator was Dr. Elise LaDouceur who serves as JPC’s Chief of Extramural Projects and Research. Her four cases featured birds across separate classes which allowed conference participants to appreciate the role of taxonomy in formulating differential diagnoses for each case.

We thank the contributor for their submission of this neat pigeon double feature. Conference participants reviewed the anatomy of the cloaca which is composed of 3 parts – the coprodeum (continuous with the intestine), the urodeum (entry of ureters and genital ducts), and the proctodeum (terminal portion). There are two lymphoid centers within the cloaca with the larger Bursa of Fabricius overshadowing a smaller dorsal proctodeal ‘lymphoglandular ridge’ near the terminus proper. The section submitted represents a dorsal sagittal section that captures the bursa, dorsal proctodeum, and external portion of the vent.

We agree that the predominant slide feature was necrotizing inflammation which is characteristic of Toxoplasma across species and tissues. We described the cellular infiltrate as ‘pleocellular’ given the mixed and significant presence of histiocytes, granulocytes, lymphocytes, and plasma cells. Zoites and schizonts were generously present in section. Finding the circovirus inclusions was more difficult, particularly on the scanned slide (one benefit of reviewing glass!) – in this case they are characteristically botryoid though slightly more eosinophilic that typically seen. Dr. LaDouceur emphasized that the loss of bursal lymphocytes with concurrent prominent interstitial tissue and cystic dilatation of follicles is characteristic of lymphoid depletion, which could be caused by multiple viral infections of the bursa; however, the presence of botryoid inclusions is diagnostic for circovirus.

We conclude our case discussion with a brief review of Isospora and Sarcocystis in birds. Notably, Isospora (Atoxoplasma) most commonly infects passerine birds, not columbiform birds, such as pigeons. Histologically, it appears as coalescing nodules to sheets of histiocytes (with intracytoplasmic zoites) and lymphocytes which may be confused for lymphoma.5,12 As the contributor mentions, Sarcocystis exhibits schizogony that differs from Toxoplasma. Tissue sarcocysts can be a helpful finding if skeletal and/or cardiac muscle is available to review. Schizogony with associated necrosis, lymphohistiocytic inflammation, and free and intracytoplasmic protozoal organisms appears similar to Toxoplasma, however.7

References:

- Abadie J, Nguyen F, Groizeleau C, Amenna N, Fernandez B, Guereaud C, et al. Pigeon circovirus infection: pathological observations and suggested pathogenesis. Avian Pathol. 2001;30:149-158.

- Anfray P, Bonetti C, Fabbrini F, Magnino S, Mancianti F, and Abramo F. Feline cutaneous toxoplasmosis: a case report. Vet Dermatol. 2005;16:131-136.

- Biancifiori F, Rondini C, Grelloni V, and Frescura. Avian toxoplasmosis: experimental infection of chicken and pigeon. Comp lmmun Microbiol Infect Dis. 1986;9:337-346.

- Dubey JP. A review of toxoplasmosis in wild birds. Vet Parasitol. 2002;106:121-153.

- Flach EJ, Dodhia HS, Guthrie A, Blake DP. Systemic isosporiasis (atoxoplasmosis) in passerine birds at the Zoological Society of London, London Zoo. J Zoo Wildl Med. 2022 Mar;53(1):70-82.

- Hoffmann AR, Cadieu J, Kiupel M, Lim A, Bolin SR, Mansell J. Cutaneous toxoplasmosis in two dogs. J Vet Diag Invest. 2012;24:636-640.

- Mete A, Rogers KH, Wolking R, Bradway DS, Kelly T, Piazza M, Crossley B. Sarcocystis calchasi Outbreak in Feral Rock Pigeons (Columba livia) in California. Vet Pathol. 2019 Mar;56(2):317-321.

- Pena HF, Moroz LR, Sozigan RKB, et al. Isolation and biological and molecular characterization of Toxoplasma gondii from Canine Cutaneous Toxoplasmosis in Brazil. J Clin Microbiol. 2014;52:4419-4420.

- Raue R, Schmidt V, Freick M, Reinhardt B, Reimar J, Kamphausen L, et al. A disease complex associated with pigeon circovirus infection, young pigeon disease syndrome. Avian Pathol. 2005;34:418-425.

- Webb JA, Keller SL, Southorn EP, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of disseminated toxoplasmosis in an immunosuppressed dog. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2005;41:198-202.

- Williams SM, Fulton RM, Render JW, Mansfield L, and Bouldin M. Ocular and encephalitis toxoplasmosis in canaries. Avian Dis. 2001;45:262-267.

- Wong TS, Stalis IH, Witte C, Kubiski SV. Unique Isospora-associated histologic lesions in white-rumped shama (Copsychus malabaricus). Vet Pathol. 2022 Sep;59(5):869-872.

- Woods LW, Latimer KS, Niagro FD, Riddell C, Crowley AM, Anderson ML, et al. A retrospective study of circovirus infection in pigeons: nine cases (1986-1993). J Vet Diagn Invest. 1994;6:154-164.