Wednesday Slide Conference, Conference 16, Case 3

Signalment:

11-month-old, male Doberman, Canis lupus familiaris, dog.

History:

The dog was presented to the referring veterinarian with a 1-month history of persisting vomiting, diarrhea, and weight loss. On abdominal ultrasound, an approximately 16 x 6 cm echogenic, heterogeneous, poorly vascularized mass was in the mesogastrium extending from the caudal aspect of the liver to the area of the urinary bladder. Peritoneal effusion and reactive intestinal serosa were also appreciated. The dog underwent laparotomy for excision of the mass, but died during surgical procedure.

Gross Pathology:

On necropsy, an 18 x 7 x 5 cm firm, poorly demarcated, tan mass was firmly adhered to the greater curvature of the gastric wall, capsule of the pancreas and serosa of the duodenum and jejunum and gastric lymph nodes. On cut surface, the mass was tan with multiple 1-4 mm yellow to green caseous areas and up to 8 cm cystic necrotic foci with viscous, yellow to brown exsudate. Along the serosa of the stomach, duodenum, and jejunum, there were multiple 2-4 cm in diameter nodules similar to the larger mass. The mucosa of the stomach and intestines was grossly normal, without ulcerations. The peritoneum was diffusely dark red with engorged blood vessels. The left testicle had an approximately 2 cm firm tan nodule within the parenchyma.

Laboratory Results:

The bloodwork revealed leukocytosis (23.160/mm3) with neutrophilia (17.602/mm3) e monocytosis (1853/mm3). Chemistry results were normal.

Frozen fragments of the mesenteric mass were submitted to DNA extraction and panfungal PCR using internal transcribed spacer (ITS) primers. Amplified DNA product was submitted for sequencing and aligned with Scedosporium apiospermum / Pseudoallescheria boydii with 98.9% identity.

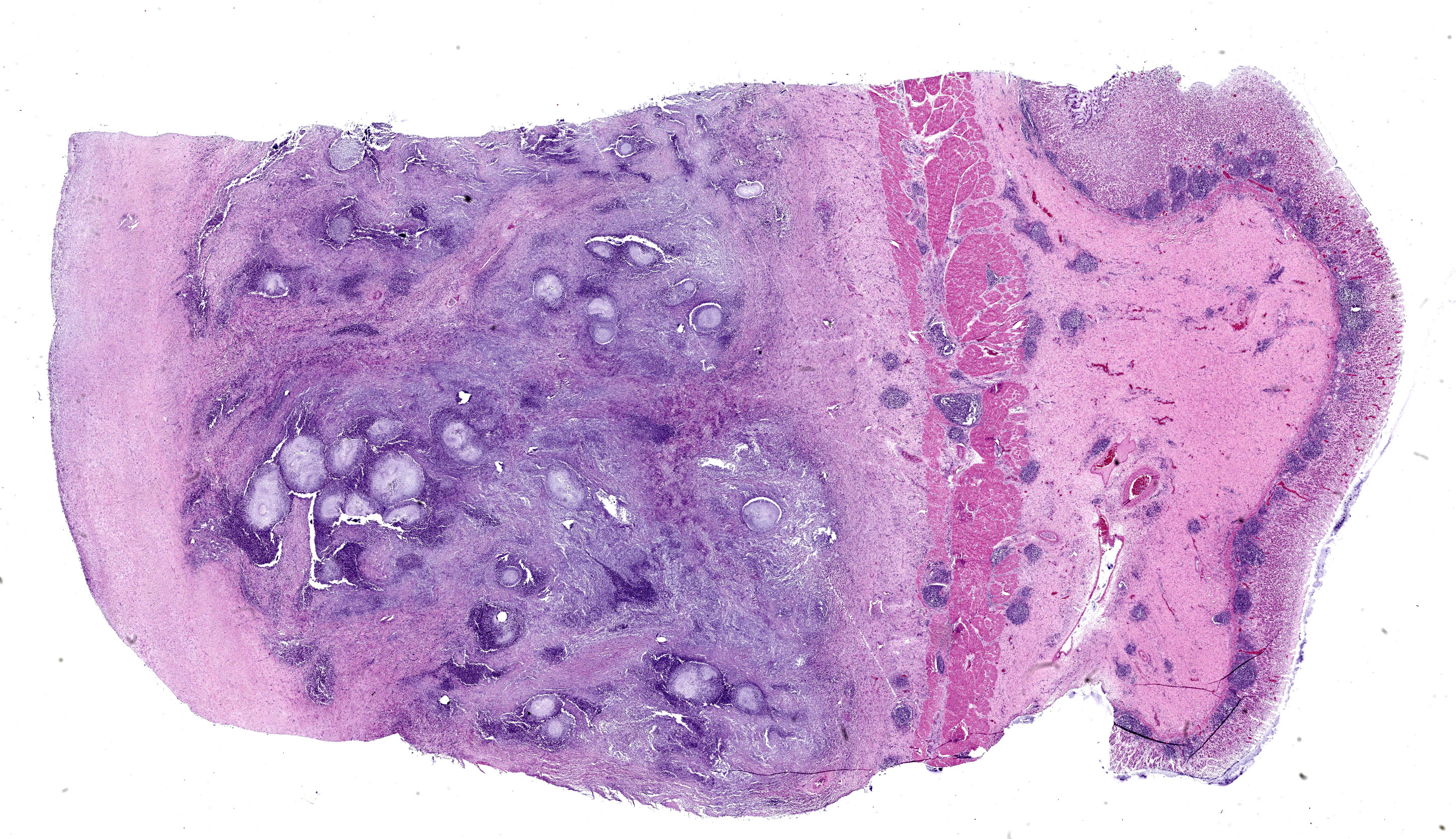

Microscopic Description:

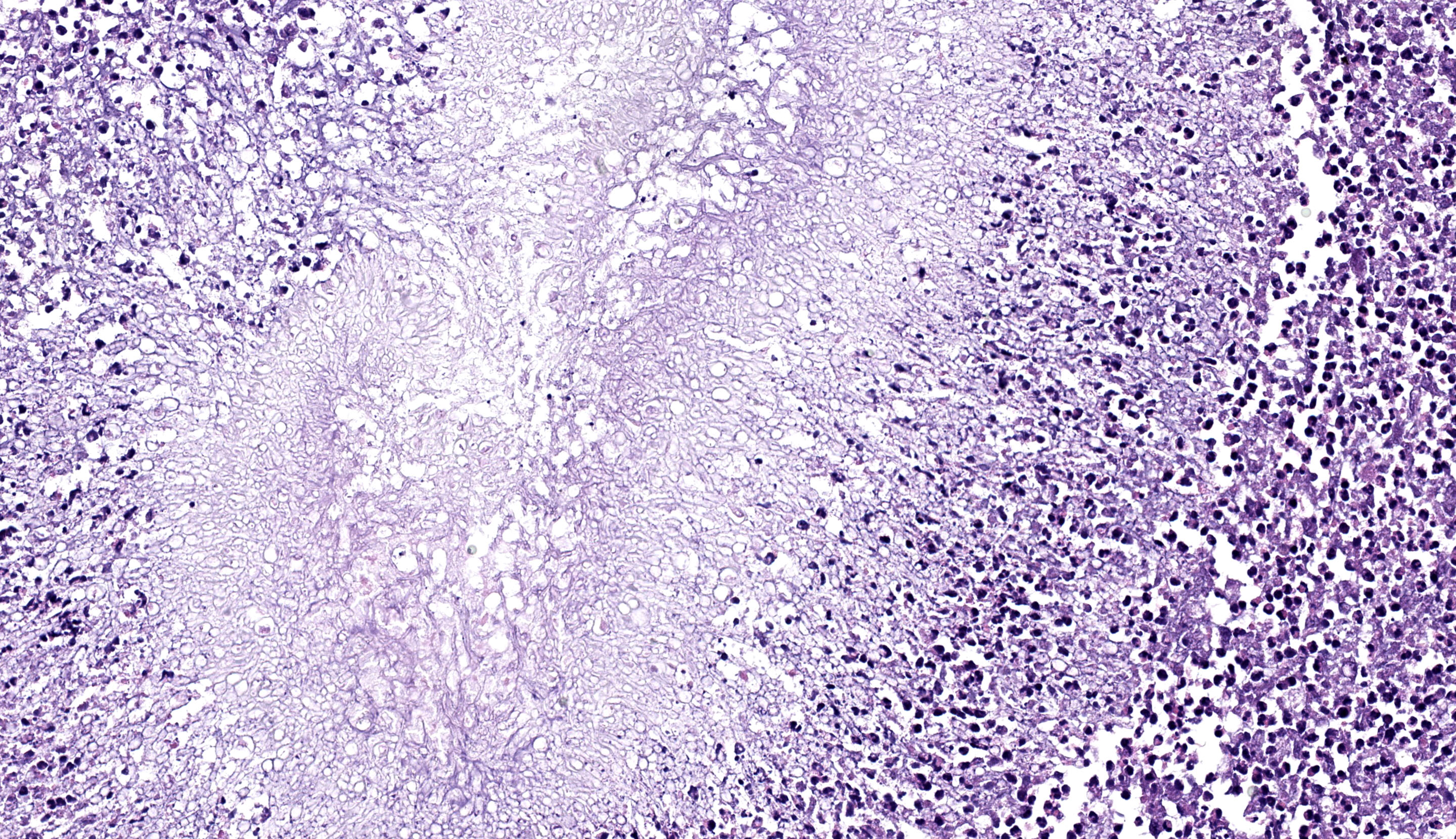

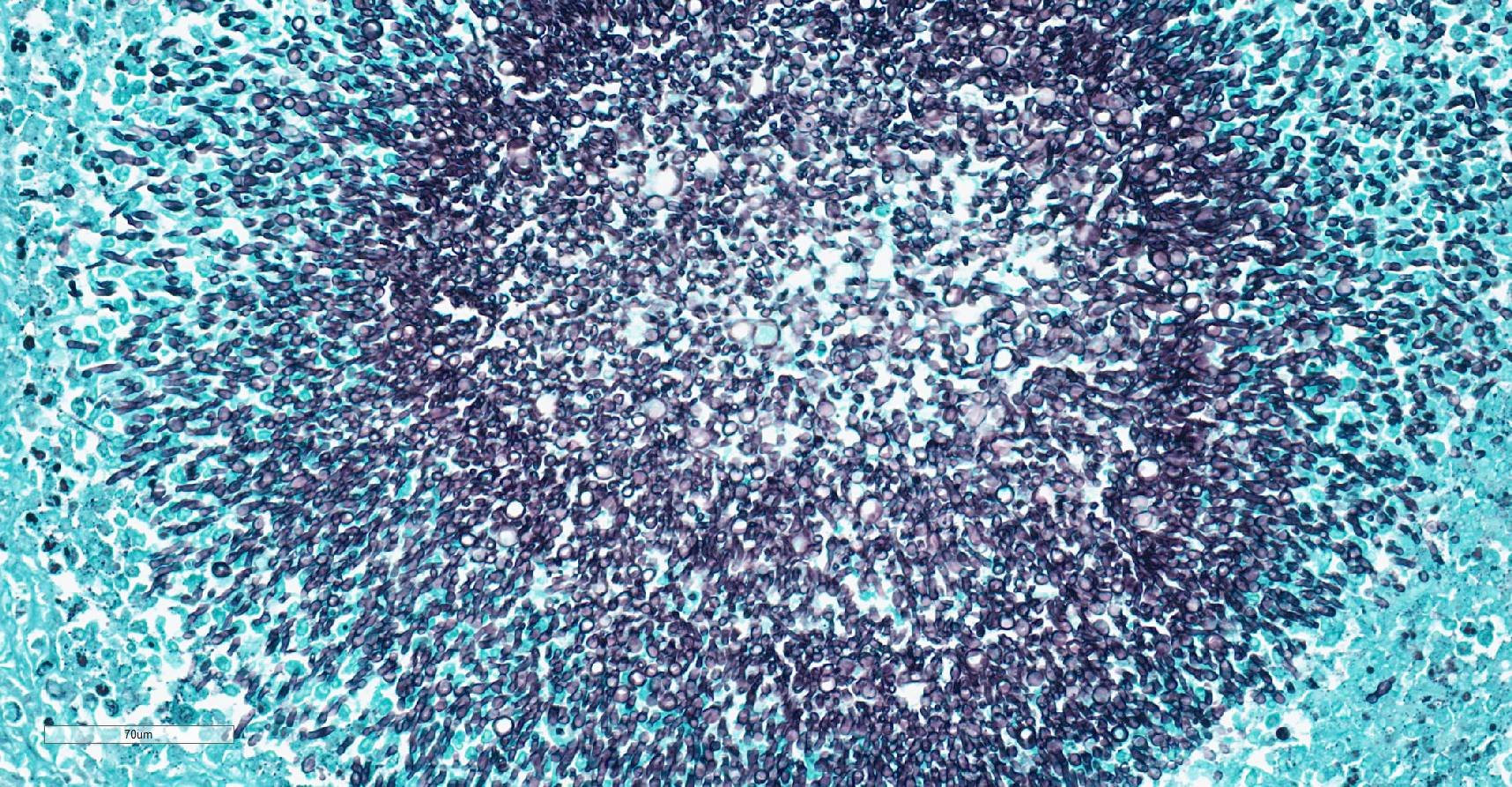

Stomach: expanding the serosa and extending into the muscularis layer and submucosa is a dense inflammatory infiltrate forming multifocal to coalescing pyogranulomas. The center of the pyogranulomas contains myriads of fungal hyphae surrounded by degenerated and intact neutrophils, cellular debris, epithelioid macrophages, macrophages with foamy cytoplasm, fewer lymphocytes, eosinophils, plasma cells, and occasional Langhans multinucleated giant cells. Hyphae are 2-3 µm in diameter wide with thin non-parallel walls containing septations, irregular branching and bulbous dilations up to 9 µm in diameter. Hyphae were positive on periodic acid Schiff and Gomori methenamine silver stain. Melanine was not detected on Fontana Masson stain. The muscularis externa and serosa are expanded by reactive fibroblasts and abundant deposition of fibrous connective tissue. Lymphoid follicles in the lamina propria are hyperplastic.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Stomach: severe, multifocal to coalescing pyogranulomatous gastritis with numerous intralesional hyphae.

Contributor’s Comment:

Fungi within the genus Scedosporium are saprophytes distributed worldwide in soil and fresh water, especially in environments rich in organic matter and manure.1,11,17 Scedosporium apiospermum was previously known as Scedosporium boydii, but they are currently classified as distinct species. Pseudoallescheria is the teleomorph or sexual stage of Scedosporium spp. and usually is not present in tissue samples.7,9

Scedosporiosis is an emerging opportunistic fungal infection described in humans and animals.5,17 In humans, infection with Scedosporium apiospermum, Scedosporium boydii and Scedosporium aurantiacum (collectively, the S. apiospermum species complex) can result in two distinct diseases: mycetoma and systemic scedosporiosis (pseudallescheriasis). Mycetoma is a chronic infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissue characterized by the production of grains.

Most human patients with systemic infection are immunocompromised and common affected organs include lungs, nasal sinuses, bone, joints, and the brain10. Infection is usually through inhalation or traumatic inoculation through the skin. Scedosporium-related pneumonia is reported after near drowning in contaminated water.

In animals, few cases of cutaneous and systemic scedosporiosis are described in dogs, cats, horses, cattle, and an elephant seal.3,4,8,14,18,21,22 In dogs, cutaneous infections are more often described in the digits, face and around the joints.5,6,15 Infections with Scedosporium spp. have been reported after cutaneous traumatic injuries and surgical procedures.6 In the present case, the distribution of the lesions suggests that the infection occurred through ingestion, although the mucosa of the affected gastrointestinal tract was intact. Gastrointestinal foreign bodies were not appreciated on gross examination and the dog had no history of previous surgical procedures. Immunosuppression and concomitant diseases are common predisposing factor for systemic infection in human patients, including infection by human immunodeficiency virus, diabetes, cystic fibrosis, neutropenia, those receiving prolonged high-dose corticosteroid therapy, or those who have undergone allogeneic bone marrow transplantation.2,13,16,17,20 In this dog, all major organs were evaluated by histopathology and there was no evidence of concomitant diseases that could have predisposed to infection or history of previous use of immunosuppressants.

Although special stains (periodic acid-Schiff and Gomori methenamine silver) highlight characteristic morphologic features of the hyphae, these can be impossible to differentiate from Conidiobolus spp., Basidiobolus spp., Aspergillus, and Fusarium spp.12,19 Fungal identification of Scedosporium spp. requires culture along with DNA sequencing or matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry.10 Scedosporiosis should be considered as a differential diagnosis for fungal pyogranulomatous gastroenteritis and peritonitis in dogs, especially when numerous fungal hyphae with bulbous dilations are observed.

Contributing Institution:

Escola de Veterinária, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG).

www.vet.ufmg.br

JPC Diagnosis:

Stomach: Serositis, pyogranulomatous, chronic-active, multifocal, severe, with numerous hyphae.

JPC Comment:

The contributor provides an interesting slide supported by an exhaustive background on Scedosporium apiospermum. The major microscopic features were readily apparent on H&E and special (fungal) stains alike. We interpreted the multifocal presence of lymphoid aggregates as secondary to the profound serosal fibrosis and the resulting decrease in gastric motility.

We differed from the contributor’s morphologic diagosis on two minor points. Similar to the discussion from Case 2, only one layer of the gastric wall is involved in the primary inflammatory process - for this reason, we describe this case as a serositis versus a gastritis. Additionally, we also noted the morphologic features of hyphae were best observed with histologic stains and not as well visualized on HE (which forms the basis of the JPC morphologic diagnosis, as special stains are not available to conference participants in advance of the conference. In this case, a silver stain best highlights the parallel walls, regular septation, irregular branching, and bulbous dilations that were generously present in section. We agree with the contributor that PCR is ideal for confirming identity of fungal agents, though morphology can help to create a prioritized list of differentials. Dr. Uzal suggested to conference participants that Zygomyces was unlikely in this case as hyphae have non-parallel wall hyphae and are pauciseptate23 whereas the hyphae in this section were regularly septate and had conspicuously (and almost perfectly) parallel walls.

References:

- Al-Yasiri MH, Normand AC, Mauffrey JF, et al. Anthropogenic impact on environmental filamentous fungi communities along the Mediterranean littoral. Mycoses. 2017;60(7):477-484.

- Berenguer J, Diaz-Mediavilla J, Urra D, et al. Central nervous system infection caused by Pseudallescheria boydii: case report and review. Rev Infect Dis. 1989;11(6):890-6.

- Coleman MG, Robson MC. Nasal infection with Scedosporium apiospermum in a dog. N Z Vet J. 2005;53(1):81-3.

- Di Teodoro G, Averaimo D, Primavera M, et al. Disseminated Scedosporium apiospermum infection in a Maremmano-Abruzzese sheepdog. BMC Vet Res. 2020;2;16(1):372.

- Elad D. Infections caused by fungi of the Scedosporium/Pseudallescheria complex in veterinary species. Vet J. 2011;187(1):33-41.

- Elad D, Perl S, Yamin G, et al. Disseminated pseudallescheriosis in a dog. Med Mycol. 2010;48(4):635-8.

- Guarro J, Kantarcioglu AS, Horré R, et al. Scedosporium apiospermum: changing clinical spectrum of a therapy-refractory opportunist. Med Mycol. 2006;44(4):295-327.

- Gupta MK, Banerjee T, Kumar D, et al. White grain mycetoma caused by Scedosporium apiospermum in North India: a case report. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2013;12(4):286-8.

- Haulena M, Buckles E, Gulland FM, et al. Systemic mycosis caused by Scedosporium apiospermum in a stranded northern elephant seal (Mirounga angustirostris) undergoing rehabilitation. J Zoo Wildl Med. 2002;33(2):166-71.

- Hospenthal DR. Uncommon Fungi and related Species. In: Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. Part III. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019: 3224-3225.

- Kaltseis J, Rainer J, De Hoog GS. Ecology of Pseudallescheria and Scedosporium species in human-dominated and natural environments and their distribution in clinical samples. Med Mycol. 2009;47(4):398-405.

- Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK. Central nervous system aspergillosis: a 20-year retrospective series. Hum Pathol. 2002;33(1):116-24.

- Kowacs PA, Soares Silvado CE, Monteiro de Almeida S, et al. Infection of the CNS by Scedosporium apiospermum after near drowning. Report of a fatal case and analysis of its confounding factors. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57(2):205-7.

- Leperlier D, Vallefuoco R, Laloy E, et al. Fungal rhinosinusitis caused by Scedosporium apiospermum in a cat. J Feline Med Surg. 2010;12(12):967-71.

- Mauldin EA, Kennedy JP. Integumentary System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 1. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2016:653- 655.

- Montero A, Cohen JE, Fernández MA, et al. Cerebral pseudallescheriasis due to Pseudallescheria boydii as the first manifestation of AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26(6):1476-7.

- Paajanen J, Halme M, Palomäki M, et al. Disseminated Scedosporium apiospermum central nervous system infection after lung transplantation: A case report with successful recovery. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2019;16(24):37-40.

- Singh K, Boileau MJ, Streeter RN, Welsh RD, Meier WA, Ritchey JW. Granulomatous and eosinophilic rhinitis in a cow caused by Pseudallescheria boydii species complex (Anamorph Scedosporium apiospermum). Vet Pathol. 2007;44(6):917-20.

- Smith CG, Woolford L, Talbot JJ, et al. Canine rhinitis caused by an uncommonly-diagnosed fungus, Scedosporium apiospermum. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2018;8(22):38-41.

- Suzuki Y, Oishi H, Matsuda Y, et al. Pneumonia with Scedosporium apiospermum and Lomentospora prolificans in a patient after bilateral lung transplantation for pulmonary hypertension: a case report. Transplant Proc. 2021;53(4):1375-78.

- Swerczek TW, Donahue JM, Hunt RJ. Scedosporium prolificans infection associated with arthritis and osteomyelitis in a horse. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2001;218(11):1800-2, 1779.

- Tsoi MF, Kline MA, Conkling A, et al. Scedosporium apiospermum infection presenting as a mural urinary bladder mass and focal peritonitis in a Border Collie. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2021;15(33):9-13.

- Rodrigues Hoffmann A, Ramos MG, Walker RT, Stranahan LW. Hyphae, pseudohyphae, yeasts, spherules, spores, and more: A review on the morphology and pathology of fungal and oomycete infections in the skin of domestic animals. Vet Pathol. 2023 Nov;60(6):812-828.