WSC 2023-2024, Conference 24, Case 3

Signalment:

1-year-old, gender not specified Nile crocodile (Crocodiles niloticus).

History:

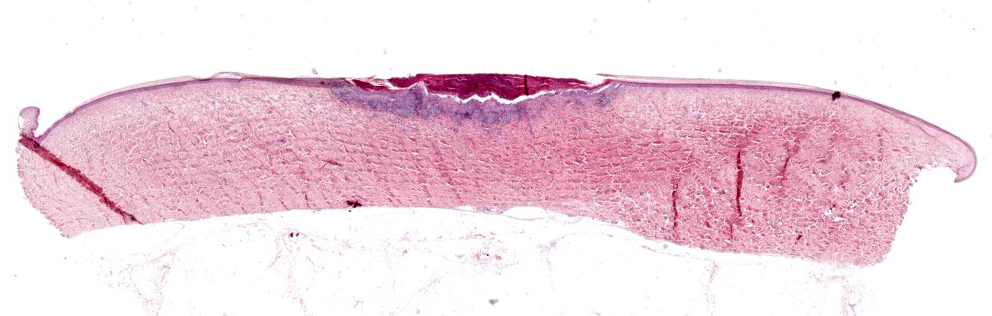

Biopsy from a farmed yearling Nile crocodile (Crocodiles niloticus) that presented with multifocal to coalescing 3-5 mm ovoid ulcerated lesions on the abdominal ventrum. There were no associated clinical abnormalities.

Gross Pathology:

Multifocal to coalescing 3-5 mm ovoid ulcerated lesions on the abdominal ventrum.

Laboratory Results:

Lesions were PCR positive for crocodile pox.

Microscopic Description:

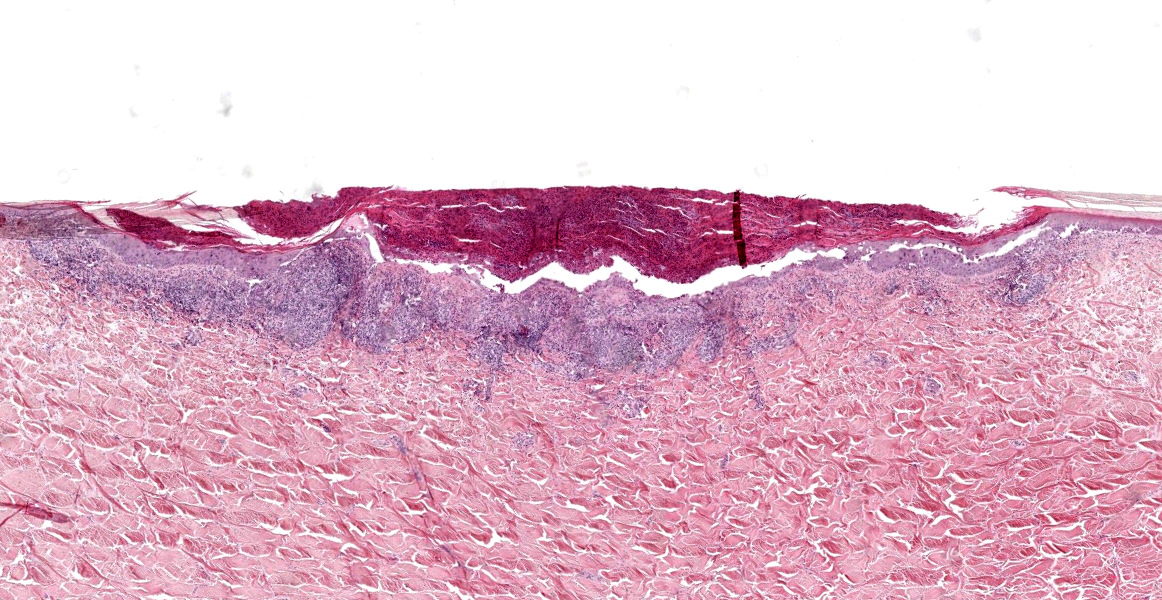

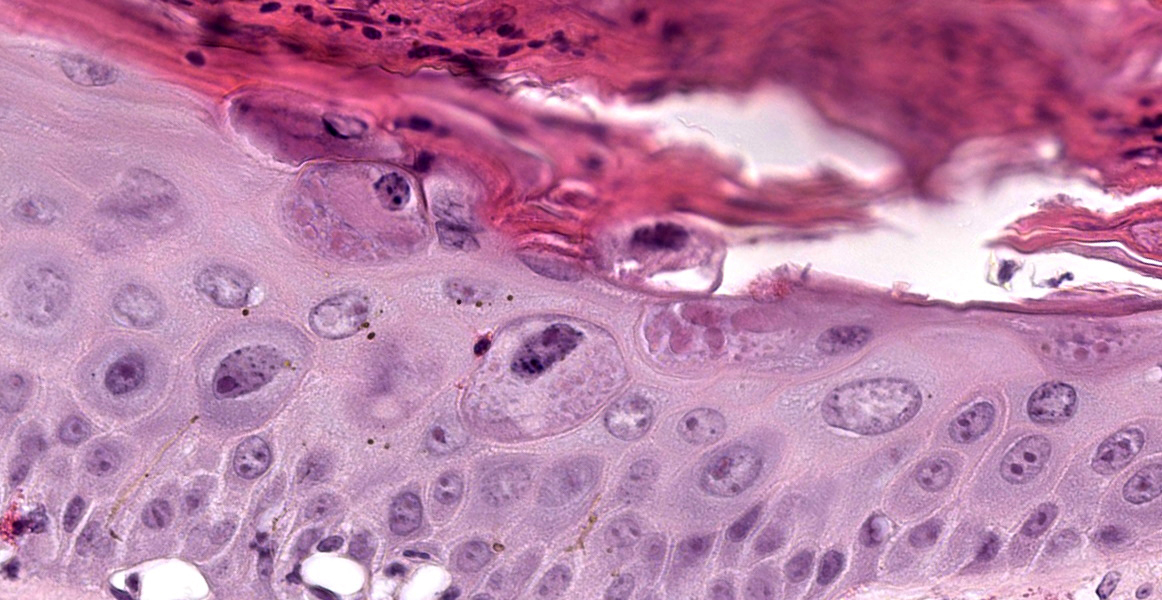

Focal erosion, ulceration and hyperplasia of the epidermis with thick adherent serocellular crust. Ballooning degeneration of keratinocytes is a feature and numerous eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions are observed.

There are marked perivascular to more widespread accumulations of admixed heterophils, lymphocytes, and macrophages within the subjacent superficial dermis.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Skin: Dermatitis, necrotizing and proliferative with ballooning degeneration and intracytoplasmic, eosinophilic inclusions consistent with poxvirus infection, Nile crocodile (Crocodiles niloticus), reptile.

Contributor’s Comment:

The pathognomonic features of keratinocyte ballooning and eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions, taken together with the clinical appearance and positive PCR result, are consistent with a diagnosis of crocodile poxvirus infection. Infection typically results in proliferative skin lesions approximately 1-3 mm diameter, grey to brown, and sessile or slightly depressed in contour. Lesions are variously encrusted, ulcerated or, less frequently, exophytic and wart-like and can occur over the entire body.3, 4 Sequelae can include opportunistic infections by Dermatophilus-like bacteria or by fungi. The presence of pox virions can be confirmed by electron microscopy with visualization of characteristic 100 nm by 200 nm virions with a dumbbell-shape with cross striations.2,4

While some members of the poxvirus family are host specific, others can infect many species.5 The Poxviridae family is subdivided into the Entomopoxvirinae and Chordopoxvirinae subfamilies and members of the latter subfamily cause disease where skin lesions are the predominant clinical sign. Currently, 29 members of this subfamily are known to infect mammals, 10 are found in birds and one species is associated with disease in reptiles including several crocodilian species.5

Poxvirus-associated disease in reptiles has been described in caimans (Caiman crocodilus), Nile crocodiles (Crocodilus niloticus), and in both saltwater (Crocodylus porosus) and freshwater (Crocodilus johnstoni) crocodiles.2 Although found in crocodilians worldwide, only three crocodile poxvirus genomes have been published to date and the source of infection remains unclear, although mosquitos have been suggested as potential vectors following infection of saltwater crocodiles.1,6

Contributing Institution:

Veterinary Sciences Centre

School of Veterinary Medicine

University College Dublin

Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland

http://www.ucd.ie/vetmed/

JPC Diagnosis:

Skin: Dermatitis, necrotizing and proliferative, focal, moderate with epidermal ballooning degeneration and intracytoplasmic viral inclusions.

JPC Comment:

This small piece of tissue packs a big punch, managing to illustrate both the characteristic histologic lesions of poxviral dermatitis and the wide variety of hosts in which the disease can occur. While the Poxviridae family is familiar to most, it likely comes a surprise to some that the family includes a small, evolutionarily divergent group of poxviruses in the genus Crocodylidpoxvirus that affects the order Crocodylia worldwide.5 The currently-characterized members of this group include Nile crocodilepox virus-1 (CPV) and saltwater crocodilepox viruses 1 and 2.6

CPV most commonly causes a nonfatal dermatitis with complete recovery which is mostly of economic importance to the commercial crocodile leather farming industry. Occasionally, however, more severe disease can develop with clinical signs of ophthalmia, rhinitis resulting in asphyxia, and debilitating illness with stunting and high mortality.1 Histopathologic features are characteristic of poxviral infection generally (necrosis, hyperkeratosis, ballooning degeneration, and intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies) as nicely illustrated by this histologic section.

The progression of poxviral dermatitis lesions has been detailed in the saltwater crocodile and classified into four stages: early active, active, expulsion, and healing.4 Early active lesions are 1-3 mm in diameter, white to grey foci of pinpoint of keratin damage. Early active lesions are histologically characterized by epidermal hyperplasia and hypertrophy with visible intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies and in intact overlying kertain layer.4 With progression to the active stage, affected surface area increases and lesions develop a distinct raised outer contour with a depressed central core of abnormal keratin. The stage is characterized histologically by disruption of the superficial keratin layer and the development of a mild perivascular lymphocytic dermal infiltrate.4

In the expulsion stage, the central core of necrotic cells is released revealing a crust of necrotic inflammatory cells that given the gross lesion an orange/tan color; the underlying epidermis at this stage is of normal thickenss and cellular morphology.4 In the final healing phase, the lesion surface area decreases, with the surface keratin appearing abnormal, though with the color of normal skin. The lesions slowly become less visible during this phase, eventually returning to an almost normal macroscopic appearance.4

CPV is most phylogenetically related to molluscum contagiosum virus, but is rather distinct from other Chordopoxviruses.1 CPV lacks many recognizable virulcence genes common to other Chrodopoxviruses, including interferon responses, intracellular signaling, and host immune response modulation. The CPV genome contains many putative genes which are speculated to perform these functions in novel ways, though none have yet been characterized.1 CPV remains a bit mysterious, with seemingly familiar gross and histomorphologic lesions that belie a unique, recently diverged, and largely unknown biological armamentarium.

Conference participants had no difficult identifying the poxviral etiology for these lesions, though there was some discussion about the size, quantity, and character of the intracytoplasmic viral inclusions, which participants felt looked slightly different from normal poxviral inclusions. The moderator, who has extensive experience with crocodile pathology and husbandry, noted that this histologic section is an excellent, quality example of crocodile skin. The moderator also directed participants to the lateral edges of the section to appreciate normal crocodile skin, which typically has a very thin epidermis. Comparing the normal skin to the lesional skin highlights the degree hyperkeratosis that is typical of poxviral dermatitis in any species.

References:

- Afonso CL, Tulman ER, Delhon G, et al. Genome of crocodilepox virus. J Virol. 2006;80(10):4978–4991.

- Buenviaje G, Ladds P, Melville L. Poxvirus infection in two crocodiles. Aust Vet J. 1992;69(1):15-16.

- Buenviaje G, Ladds P, Martin Y. Pathology of skin diseases in crocodiles. Aust Vet J. 1998;76(5):357-363.

- Moore RL, Isberg SR, Shilton CM, Milic NL. Impact of poxvirus lesions on saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) skins. Vet Microbiol. 2017; 211:29-35.

- Oliveira G, Rodrigues R, Lima M, Drumond B, Abrahão J. Poxvirus host range genes and virus–host spectrum: a critical review. Viruses. 2017;9(11):331.

- Sarker S, Isberg SR, Milic NL, Lock P, Helbig KJ. Molecular characterization of the first saltwater crocodilepox virus genome sequences from the world’s largest living member of the Crocodylia. Sci Rep-UK. 2018;8(1):5623.