WSC 2023-2024, Conference 25, Case 3

Signalment:

9-year-old female breed unspecified rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus).

History:

The owner noted bloody urine for a few weeks and hemorrhagic urine was found on urinalysis. The clinician suspected uterine adenocarcinoma based on clinical findings, so the patient was spayed.

Gross Pathology:

The uterus contained an 8cm mass.

Laboratory Results:

Hematuria, otherwise no significant findings.

Microscopic Description:

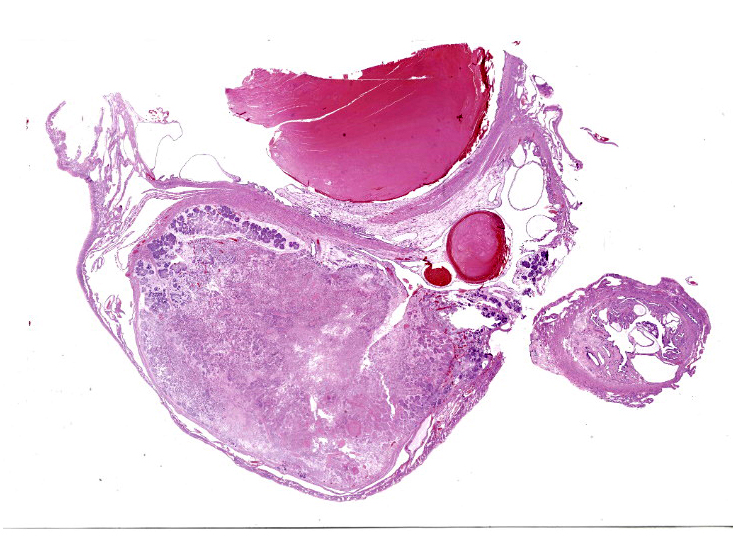

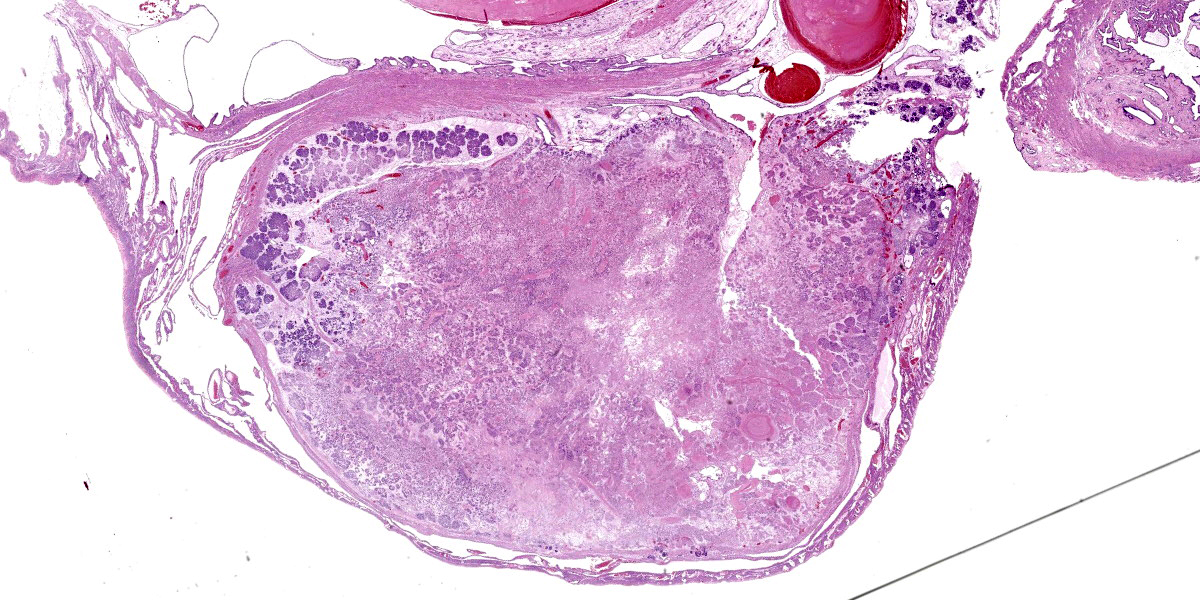

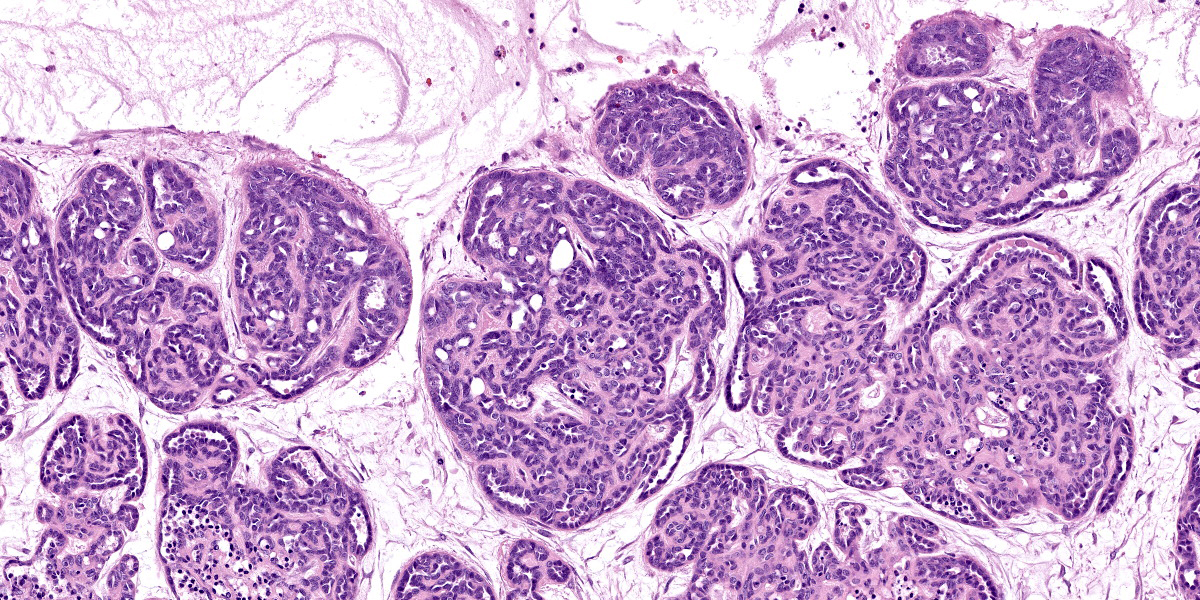

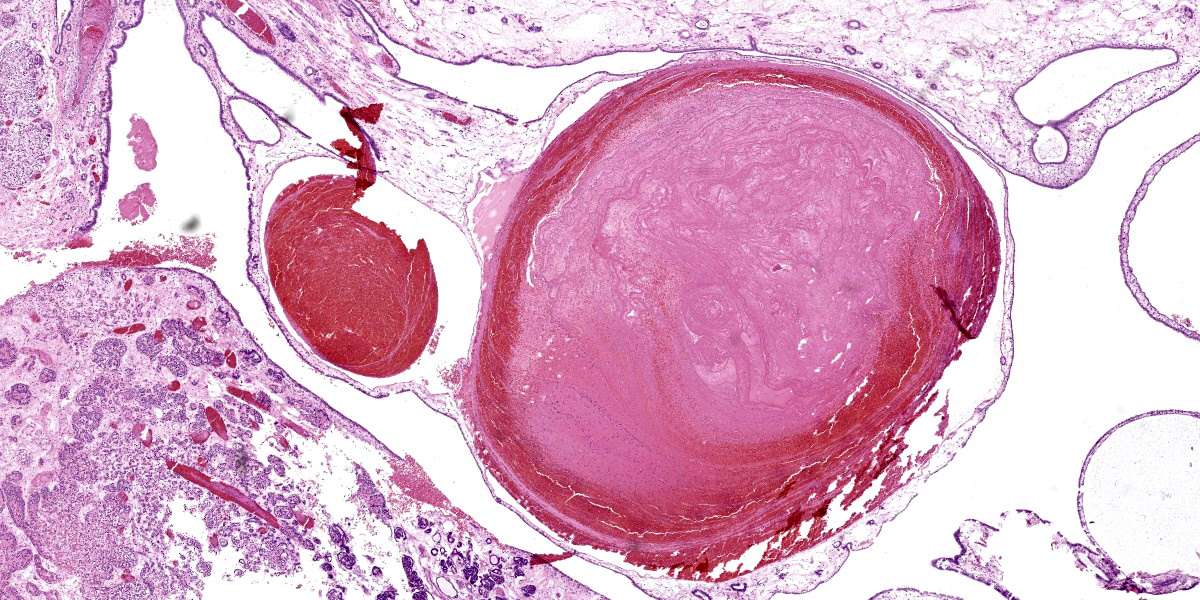

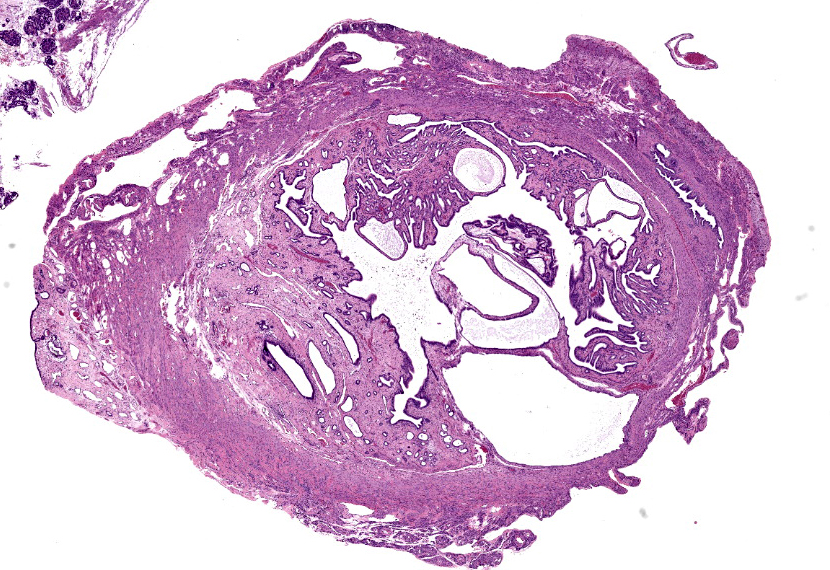

Uterus: Multifocally and transmurally infiltrating and effacing the uterine wall is an unencapsulated, densely cellular, poorly demarcated neoplasm composed of epithelial cells arranged in tubules, acini, and solidly cellular areas on a variably dense collagenous to myxomatous stroma. Neoplastic cells have indistinct cell borders, a small amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm, and a round to oval nucleus with finely stippled chromatin and indistinct nucleoli. Anisocytosis and anisokaryosis are mild, and there are less than 1 mitotic figures per 2.37mm.2 Neoplastic tubules are ectatic with fronds of neoplastic epithelial cells bulging into the lumina, and lumina are often filled with eosinophilic proteinaceous and/or mucinous exudate admixed with variable amounts of necrotic cellular debris. There is abundant predominantly coagulative necrosis at the center of the neoplastic mass characterized by loss of differential staining with retention of architecture. The non-neoplastic uterine mucosal epithelium is multifocally hyperplastic, and uterine glands are multifocally dilated, forming ectatic cysts up to 2 mm in diameter lined by attenuated epithelium (cystic endometrial hyperplasia). Arising from the endometrium and projecting into the uterine lumen, there are several cross sections of markedly dilated, endothelial-lined veins (endometrial venous aneurysm) measuring up to 5 mm in diameter. These veins are subtotally occluded by large fibrin thrombi that often contain well-defined lines of Zahn, low numbers of enmeshed erythrocytes and leukocytes, and a rare dusting of mineral in areas of coagulative necrosis.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

- Uterus: Uterine adenocarcinoma with vascular invasion.

- Uterus: Endometrial venous aneurysm with thrombosis and rare mixed bacteria.

- Uterus: Cystic endometrial hyperplasia, multifocal, moderate.

Contributor’s Comment:

Uterine adenocarcinoma is often considered the most common spontaneous neoplasm of domestic rabbits, although a recent large-scale study found that trichoblastomas and mammary tumors may surpass uterine adencarcinomas in frequency of diagnosis.1-3,6 The incidence of uterine adenocarcinoma increases with age, affecting approximately 80% of 5-6 year old does; most animals in research facilities and commercial rabbitries are relatively young, which explains why this tumor is infrequently seen in this in these facilities.1,3 Uterine adenocarcinomas may be multicentric within the uterus, and may involve both uterine horns.1,3 Metastasis to the lung is most common; metastasis to the liver and intra-abdominal carcinomatosis are also commonly reported.1,3 Intratumoral necrosis is common.1,3 Uterine adenocarcinomas are often concurrently diagnosed with endometrial hyperplasia.2,3,6,10 Additionally, one study found that, of 84 uterine adenocarcinomas, 10 had concurrent uterine leiomyoma or leiomyosarcoma.2

Endometrial hyperplasia follows second to uterine adenocarcinoma in frequency of diagnosis in rabbit uteri and is the most commonly diagnosed non-neoplastic uterine lesion in rabbits.1,3,6 The incidence increases with age, although it has been reported in rabbits less than 1 year of age.3,6,10 It is often cystic and is often diffuse.2,3 Endometrial hyperplasia is controversially considered to be a pre-neoplastic lesion by some, and is considered hormonally induced.1,2,3

Endometrial venous aneurysms were first reported in 1992 in rabbits and have yet to be reported in any species other than lagomorphs.4 They have been reported in New Zealand White rabbits,4 unspecified breeds of pet rabbits,3,5 and a Holland lop rabbit.7 They consist of venous varices that project from the endometrium into the uterine lumen. They have been reported in nongravid, multiparous does, but no predisposing factors have been identified.1,3 They may cause uterine distension with subsequent abdominal enlargement.1,4,7 The venous aneurysms may rupture, resulting in periodic bleeding into the uterine lumen (hemometra) with subsequent urogenital bleeding/hematuria, and clotted blood is often noted within the uterine lumen at necropsy.1,2,4,7 In a recent large-scale study of genital tract pathology in female pet rabbits, Bertram and colleagues identified endometrial venous aneurysms in 1.6% (n=14) of all post-mortem examinations of entire female rabbits and in 3.3% (n=5) of all uterine biopsy samples, with a median age of 32 months.3 In post-mortem examinations in this study, the endometrial venous aneurysms were considered incidental in 4 of the 14 rabbits with this diagnosis.3 In another large-scale study of uterine lesions in 1,928 rabbits, endometrial venous aneurysms were reported in 8 rabbits, none of which had clinical signs.9 Ovariohysterectomy is considered curative and is recommended due to the risk of hemorrhage.5,7

All three of these uterine lesions (uterine adenocarcinoma, cystic endometrial hyperplasia, and endometrial venous aneurysm) can result in hematuria; all three of these lesions are present in this case, and hematuria was clinically noted and confirmed via urinalysis in this case.1 Hematuria and/or serosanguinous vaginal discharge are clinical signs that should raise suspicion of uterine disease.6 Other potential causes of hematuria in rabbits include uterine polyps, cystitis, urinary bladder polyps or tumors, pyelonephritis, and renal infarction.1 Of note, differentials for hematuria in rabbits include pigmented urine due to crystals, porphyrin, or bilirubin; a urinalysis is required to differentiate between these causes.1

Contributing Institution:

Tri-Service Research Laboratory

https://www.afrl.af.mil/

JPC Diagnosis:

- Uterus: Uterine adenocarcinoma.

- Uterus: Endometrial venous aneurysm.

- Uterus: Cystic endometrial hyperplasia, diffuse, severe.

JPC Comment:

This dazzling slide, a lagomorph uterine lesion party pack, delights from subgross and closer inspection in equal measure, and the contributor provides excellent summaries of the component lesions. The endometrial venous aneurysms are particularly striking and, of the trio of uterine conditions vying for attention, the most uncommon.

Aneurysms occur when the quality or quantity of the connective tissue within the vascular wall is compromised.7 In humans, aneurysm formation has been associated with conditions such as defective synthesis of elastin or collagens I and III, vitamin C deficiency, atherosclerosis, systemic hypertension, pregnancy, or trauma.7 In the few reported cases of endometrial venous aneurysm in rabbits, no predisposing factors have been identified, leading to the classification of this condition in rabbits, for now, as congenital.7

The primary clinical signs associated with endometrial venous aneurysms are a palpably enlarged uterus and, as the contributor notes, hematuria. These symptoms are not specific and further diagnostics are typically required. In reported cases, hematologic parameters have shown little diagnostic value, though the degree of anemia may provide clues to chronicity and the amount of blood loss suffered in cases of severe aneurysm rupture.7 Plasma chemistry changes may include hyperglycemia and high creatine kinase, likely due to handling stress rather than any derangement caused by the endometrial aneurysm.7

Histologically, the weakened vessel wall can lead to massive dilation of the vein which, as in this case, can be rather obtrusive and, if we’re being honest, a little gaudy. The focally dilated vein maintains a complete endothelial lining of attenuated cells that expands the surrounding endometrial tissue. The attenuated wall may exhibit loss of smooth muscle cells and replacement with fibrous connective tissue components such as collagen or fibroblasts.7 Within the vein, blood and thrombi are usually present, with thrombi characterized by varying amounts of organization, inflammatory cells, and hemosiderin resulting from erythrocyte degradation.7

Due to the risk of sudden, severe hemorrhage, venous aneurysms carry a poor to grave prognosis unless ovariohysterectomy is performed.7 Additional sequelae include thromboembolism and recurrent bouts of excessive bleeding. Prognosis is good with ovariohysterectomy; however, it is still unknown whether this condition is truly congenital and, if so, whether endometrial venous aneurysm indicates a greater risk of aneurysm in other anatomic locations.7 While there is currently no evidence of an association with a generally heightened risk of aneurysm, more research is needed to determine the prevalence and underlying pathogenesis of this uncommon, striking condition.

Discussion of this case focused generally around the difficult in distinguishing endometrial hyperplasia from neoplasm, and the general consensus was that these two entities likely exist on a neoplasm, though evidence is currently lacking. The moderator discussed a long list of causes for hematuria in rabbits before dropping the inconvenient fact that rabbit urine can normally be red under certain conditions, so be careful about hopping to conclusions. Physiologically normal, red urine should be relatively clear, while true hematuria will have the characteristic opacity of blood.

Discussion of the morphologic diagnosis was similarly straightforward; however, conference participants were unable to identify the vascular invasion or the bacteria noted by the contributor on the section examined at conference and these features were consequently omitted from the diagnoses.

References:

- Barthold SW, Griffey SM, Percy DH. Pathology of Laboratory Rodents and Rabbits. 4th ed. John Wiley and Sons, Inc.;2016:256,310,320.

- Baum B. Not just uterine adenocarcinoma – neoplastic and non-neoplastic masses in domestic pet rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus): a review. Vet Pathol. 2021;58(5): 890-900.

- Bertram CA, Müller K, Klopfleisch R. Genital tract pathology in female pet rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus): a retrospective study of 854 necropsy examinations and 152 biopsy samples. J Comp Pathol. 2018;164:17-26.

- Bray MV, Weir EC, Brownstein DG, Delano ML. Endometrial venous aneurysms in three New Zealand white rabbits. Lab Anim Sci. 1992;42(4):360-362.

- Dettweiler A, Mundhenk L, Brunnberg L, Müller K. Fatal endometrial venous aneurysms in two pet rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus). Kleintierpraxis. 2012;57:69-75.

- Kunzel F, Grinniger P, Shibly S, et al. Uterine disorders in 50 pet rabbits. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2015;51(1):8-14.

- Reimnitz L, Guzman DSM, Alex C, Summa N, Gleeson M, Cissel DD. Multiple endometrial venous aneurysms in a domestic rabbit (Oryctolagus Cuniculus). J Exot Pet Med. 2017;26:230-237.

- Saito K, Nakanishi M, Hasegawa A. Uterine disorders diagnosed by ventrotomy in 47 Rabbits. J Vet Med Sci. 2002; 64(6):495-497.

- Settai K, Kondo H, Shibuya H. Assessment of reported uterine lesions diagnosed histologically after ovariohysterectomy in 1,928 pet rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2020; 257(10):1045-1050.

- Walter B, Poth T, Bohmer E, Braun J, Matis U. Uterine disorders in 59 rabbits. Vet Rec. 2010;166(8):230-233.