CONFERENCE 10, CASE III:

Signalment:

12-year-old, intact female, dog (Canis lupus familiaris)

History:

The dog was submitted to a local veterinary clinic for computed tomography examination. Imaging revealed a tumor of the right adrenal gland measuring 2.5 x 2 cm adjacent to the caudal caval vein. There was no evidence for an intracaval infiltration or a thrombosis of the caval vein but infiltration of the phrenicoabdominal vein was detected. Both ovaries showed multiple cysts. The pre-surgical blood work showed a mildly decreased amount of lymphocytes (0.82, range: 1.05 – 5.1 M/l). Low-dose dexamethasone suppression test revealed inadequately suppressed cortisol secretion with plasma cortisol concentrations of 3.5 µg/dl after three hours, and 3.7 µg/dl after 8 hours of dexamethasone administration, respectively. During surgery, the right adrenal gland including the phrenicoabdominal vein and both ovaries were removed and submitted for histological examination.

Laboratory Results:

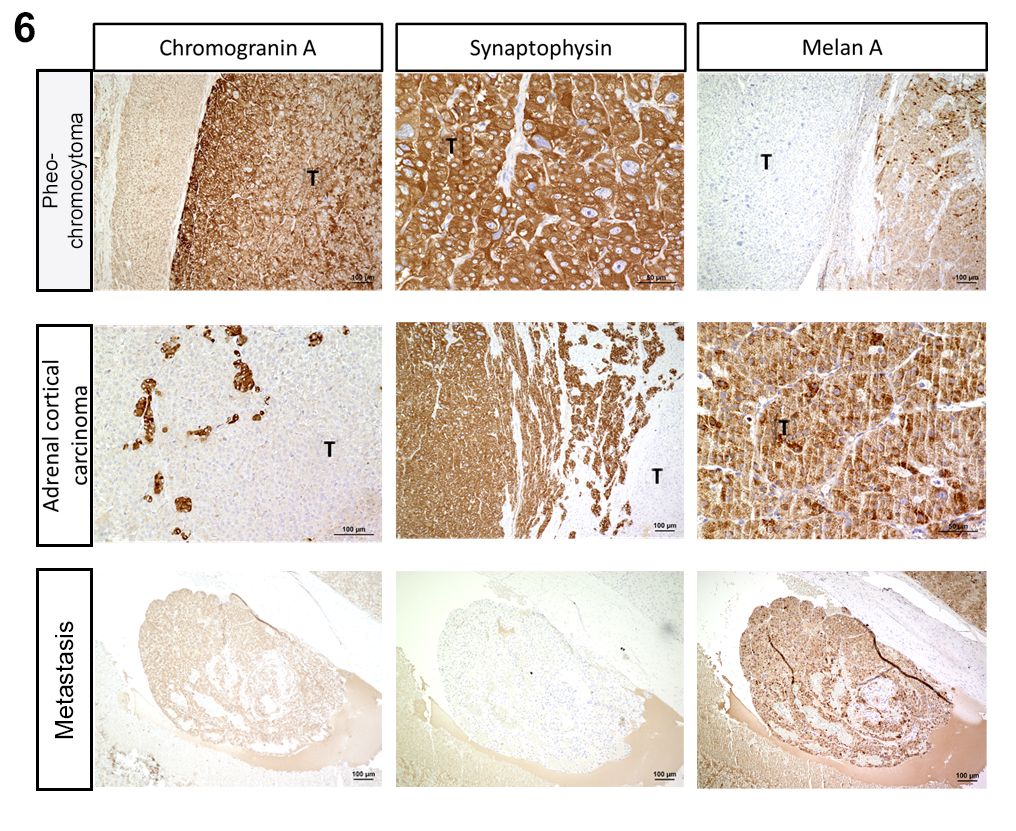

The adrenal sample was immunostained using the ABC method with commercially available antibodies specific for chromogranin A, synaptophysin and Melan A. The larger of the two proliferations stained positive for Melan A, the smaller one stained positive for chromogranin A and synaptophysin. The intravascularly detected cellular aggregate also stained positive for Melan A.

Microscopic Description:

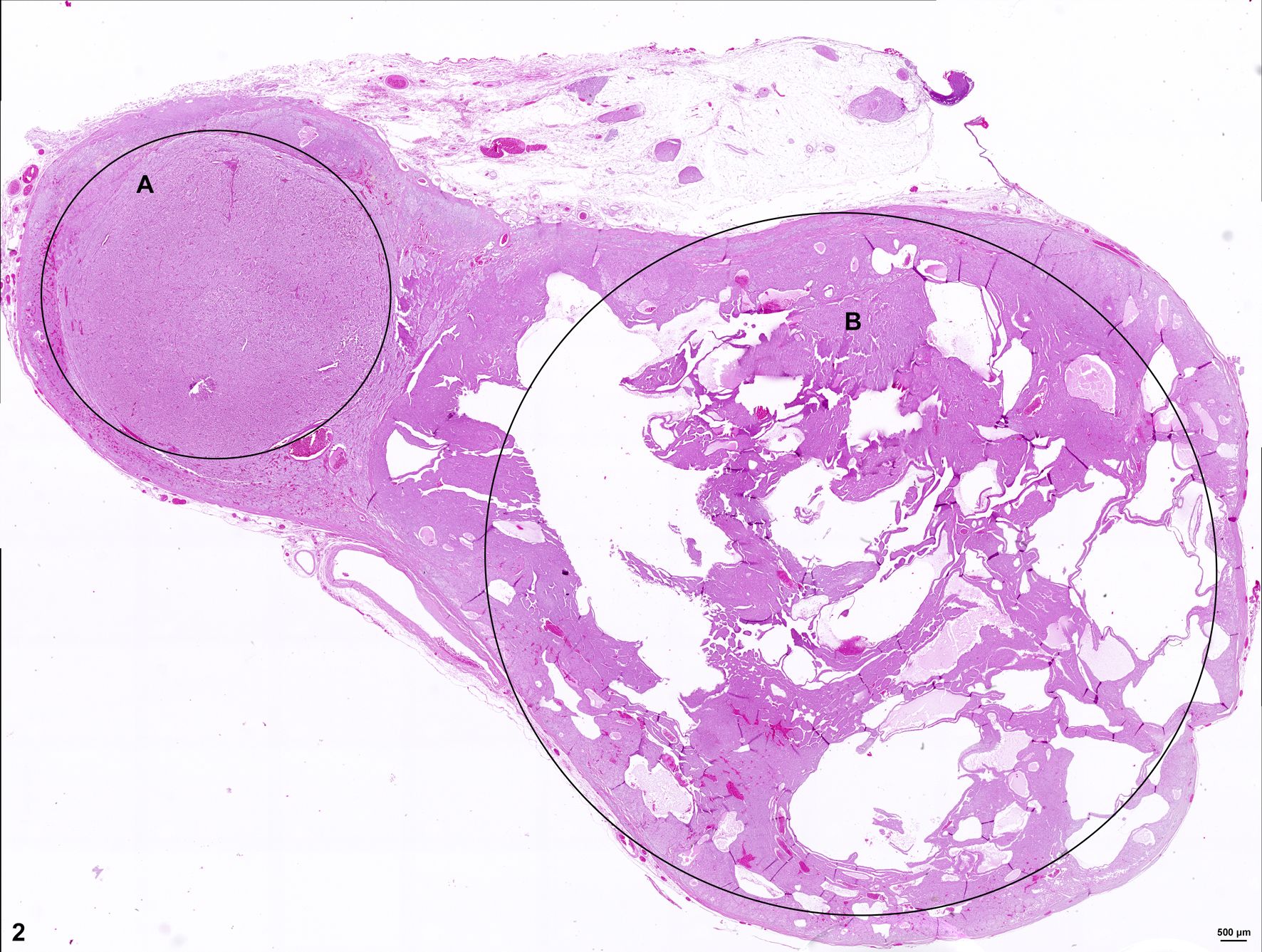

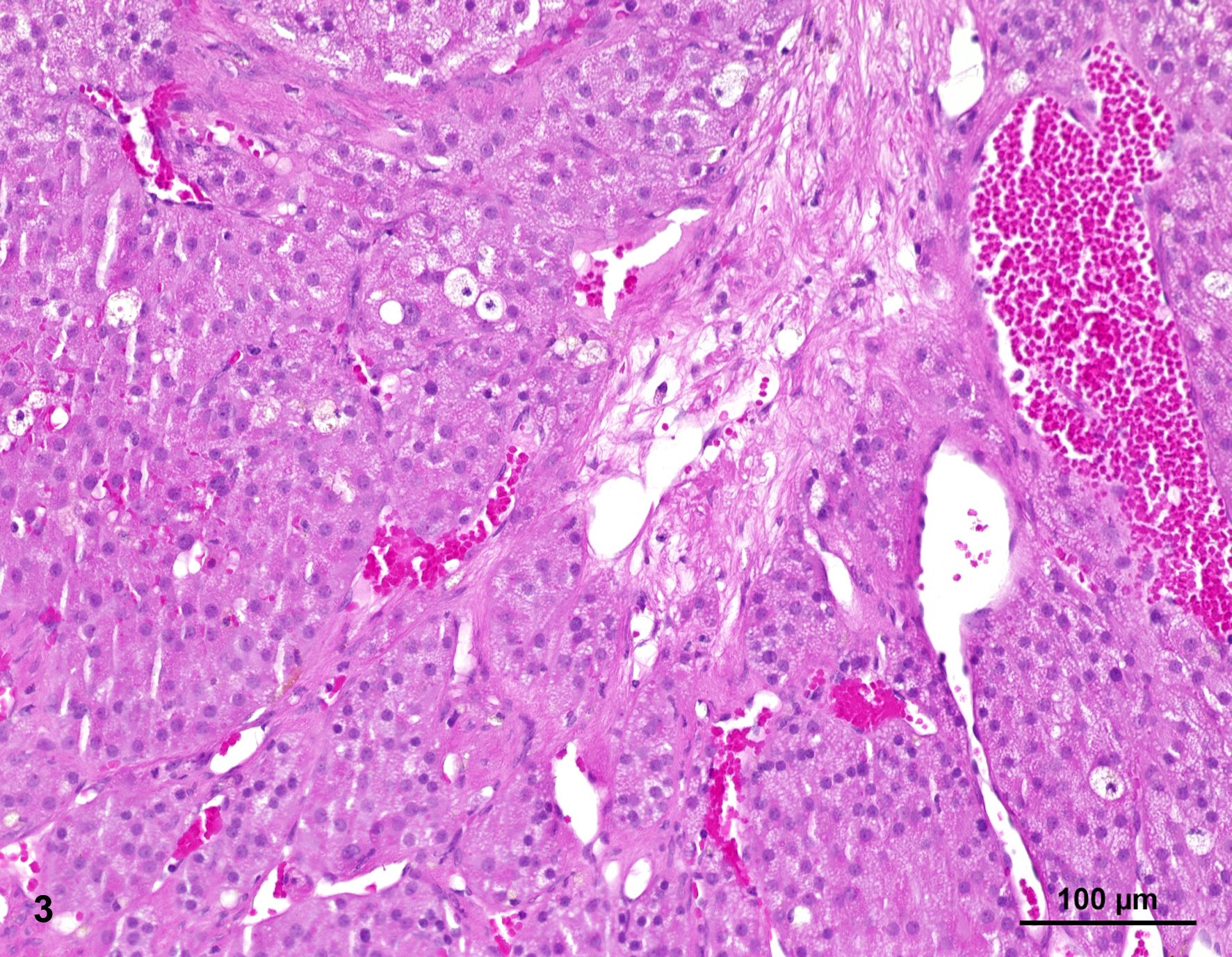

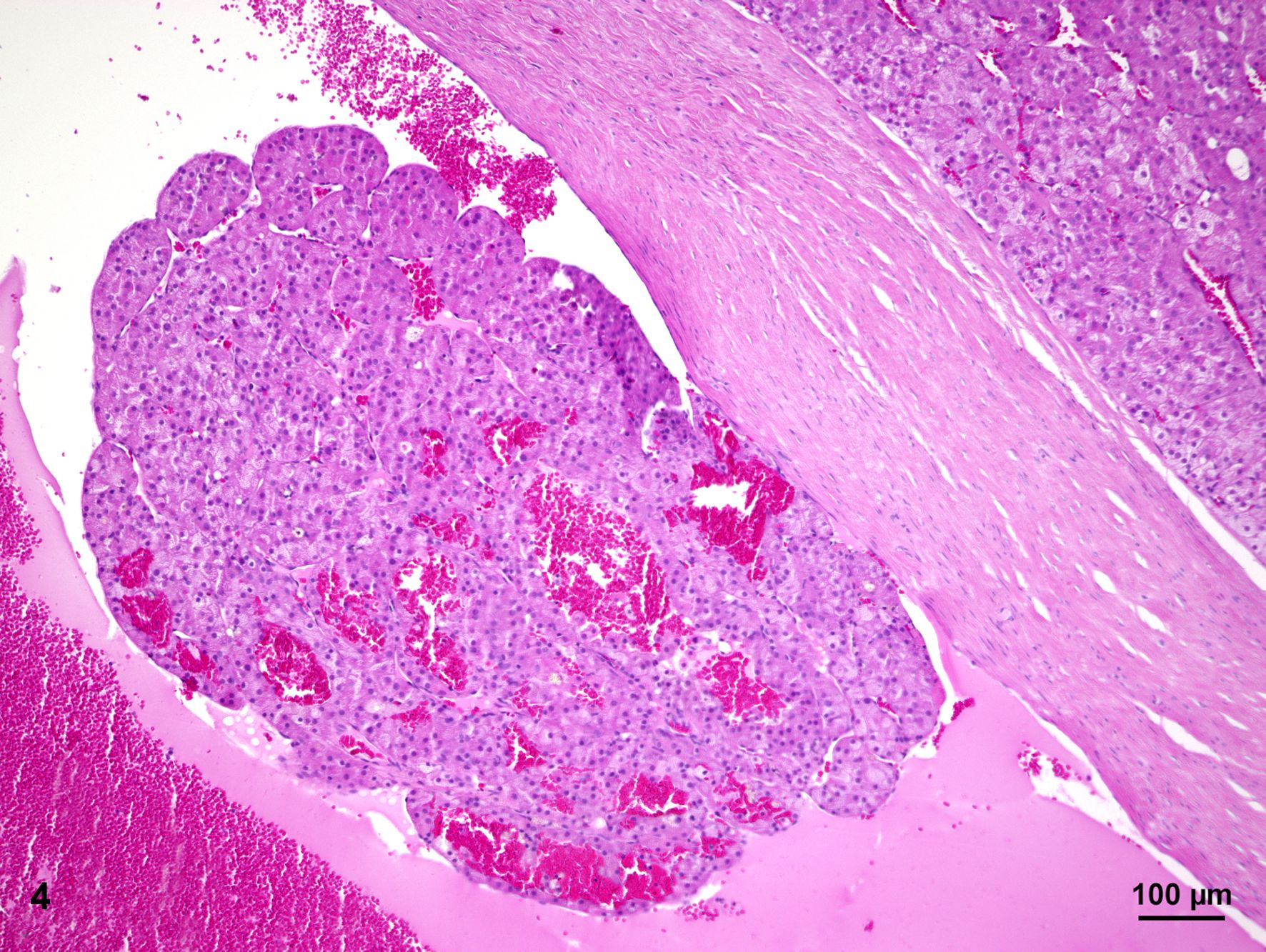

Histologically, two separate neoplastic proliferations are found in the adrenal gland. Both nodules are clearly circumscribed, expansile and separated from each other by normal adrenal tissue (Fig. 2). The larger, more cortically located proliferation measures approximately 1.4 cm in diameter. The nodular, moderately cell-rich, incompletely encapsulated, focally infiltrative mass is characterized by a predominantly solid growth pattern consisting of trabeculae of variable width, partly separated by optically empty or blood-filled spaces (dilated sinusoids). Polygonal, neoplastic cells measure approximately 15 µm in diameter (Fig. 3). The cells show distinct cellular borders and contain a moderate amount of a homogenous eosinophilic, partly highly vacuolated cytoplasm. The centrally located round nucleus displays a moderate amount of heterochromatin and one basophilic nucleolus. There is mild anisocytosis and -karyosis. Mitotic figures are not evident. The cells are accompanied by a scant fibrovascular stroma. Focally, a large aggregate of these tumor cells is present in a blood vessel (angiosis carcinomatosa) (Fig. 4).

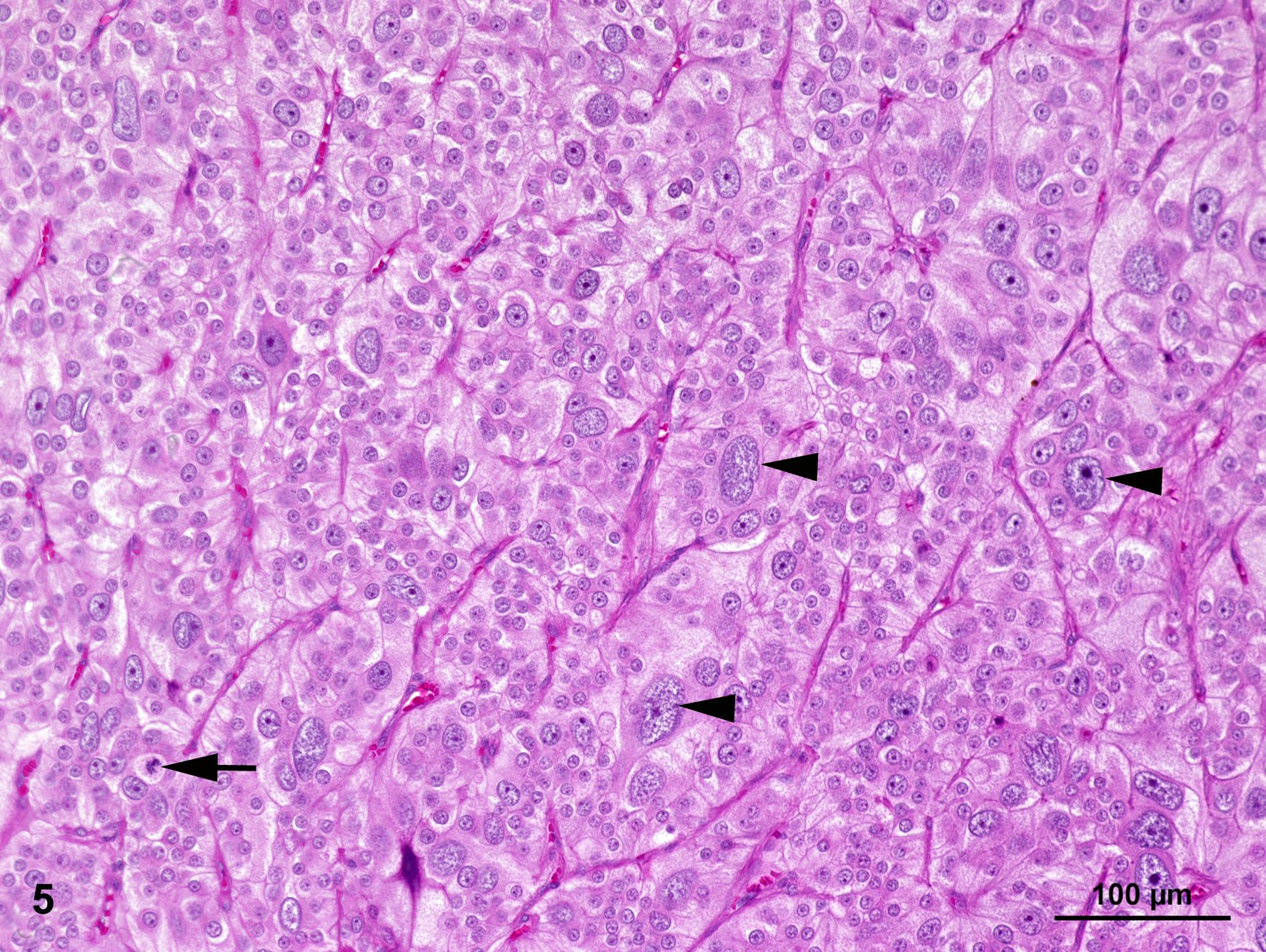

The smaller nodule, located within the medullary area of adrenal gland measures approximately 0.5 cm in diameter. The well demarcated encapsulated neoplastic mass shows predominantly expansile growth of small polygonal cells measuring approximately 10-12 µm in diameter. Cells are arranged in small lobules and packages separated by thin, fibrous septa (neuroendocrine packaging; Fig. 5). Neoplastic cells are characterized by distinct cell borders, a moderate amount of fine granular, brightly eosinophilic cytoplasm, and a slightly eccentrically located, round, moderately heterochromatin-rich nucleus with up to one distinct nucleolus. There is a moderate anisocytosis and –karyosis. Multifocally, cells measuring up to 30 µm in size with karyomegaly are present. Up to 2 mitotic figures are found per high power field (400x).

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Adrenal gland: adrenocortical carcinoma with angiosis carcinomatosa and pheochromocytoma, canine.

Contributor’s Comment:

The submitted case represents an unusual double lesion of the adrenal gland consisting of concurrent emergence of an adrenocortical carcinoma and a pheochromocytoma. Interestingly, when the dog was first presented to the clinicians, the animal did not show any obvious clinical signs of an altered adrenal function indicating a functional cortical or medullary neoplasia (excessive cortisol and/or catecholamine secretion).

Adrenocortical carcinomas occur in cattle, cats and elderly dogs and are also infrequently described in other species.12,13 They tend to be larger than adenomas and bilateral occurrence is observed more frequently.10,12,13 Affecting the zona fasciculata as well as the zona reticularis,2 they often exhibit an infiltrative growth pattern into the adjacent tissue including the caudal caval vein, where large tumor-cell aggregations can form.5,12,13

Adrenocortical tumors can be found in 10-20% of dogs with Cushing syndrome,6 and severe atrophy of the contralateral adrenal gland occurs in functional neoplasms due to a negative endocrine feedback loop.12,13 It is estimated that most of the occurring adrenocortical tumors in dogs (up to 80%) are adrenocortical carcinomas.4 Common sites for metastases are liver and lung.12,13 The functional variants (endocrinologically active) of adrenocortical tumors usually secrete a massive amount of cortisol causing hyperadrenocorticism.2,6,11 Clinical signs associated with functional adrenocortical tumors are polydipsia and polyuria, pendulous abdomen, polyphagia, muscle weakness, hypokalemia, hypertension, atrophic dermatosis with thin skin and hair loss as well as bilateral, symmetrical hypotrichosis or alopecia, hyperpigmentation scaling, comedones, and calcinosis cutis.4,9,10,11,14

Neoplastic cells of adrenocortical tumors typically show a specific immunoreactivity with antibodies targeting Melan-A, α-inhibin, vimentin, neuron specific enolase. Expression of synaptophysin may be variable.5,12,13 The larger proliferation in the presented case as well as the intravascularly located neoplastic cells stained immunopositive for Melan-A which proves the presence of an adrenal cortical carcinoma.

Pheochromocytomas represent the most common tumor of the adrenal medulla and mostly occur in older dogs with no gender or breed predisposition. They can also be found in cattle and horses,12,13 and are described in humans too.1,3,8 They represent catecholamine-secreting tumors of the neuroectoderm-derived, chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla or sympathetic ganglia, also termed sympathetic paragangliomas. They are composed of epinephrine-secreting cells, norepinephrine-secreting cells or both and occur mostly unilaterally and vary greatly in size.1,3,7,12,15 These tumors often go along with clinical signs such as tachycardia, edema, panting, cardiac hypertrophy, hypertension, anorexia, lethargy, ascites, polyuria and polydipsia as well as diarrhea and vomiting resulting from excessive secretion of catecholamine.3,7,12,13,15 In severe cases, the term ‘pheochromocytoma crisis’ is used to describe a serious complication characterized by obtundation, shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation, seizures, rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure.1 Malignancy of these tumors is assumed when invasion of the adrenal capsule and/or the caudal vena cava and the aorta or the surrounding tissue with potential metastases in distant organs is present.1,5,12,13,15 Common sites for metastasis are adjacent lymph nodes, kidney, liver, spleen, lung and bone.1,3,15 The pheochromocytoma of the presented case does not clearly show capsular invasion and/or an infiltrative growth pattern. However, especially the increased mitotic rate as well as the marked amount of pleomorphic cells can be interpreted as indications of a possible precancerous transformation.

During necropsy, a pheochromocytoma may present itself as a large mass occupying the entire adrenal gland, which is partly surrounded by a thin, compressed rim of adrenal cortex, sometimes forming small nodules.15 Small pheochromocytomas remain confined to the adrenal medulla and are well encapsulated. The tissue shows light brown to yellow-red coloring emerging from hemorrhage and necrosis.

Immunohistological expression of chromogranin A and synaptophysin can be used to confirm the diagnosis.1,5,12,13 In this case, the neoplasm stained immunopositive for chromogranin A and synaptophysin which confirms a pheochromocytoma in this case.

Contributing Institution:

Department of Pathology, University of Veterinary Medicine, Hannover, Buenteweg 17, 30559 Hannover, Germany.

http://www.tiho-hannover.de/kliniken-institute/institute/institut-fuer-pathologie/

JPC Diagnosis:

- Adrenal gland, cortex: Adrenocortical adenoma

- Adrenal gland, medulla: Pheochromocytoma.

JPC Comment:

This third case is another ‘two-fer’ case that the contributor has skillfully presented.

We agree with the contributor that the smaller neoplasm best represents a pheochromocytoma, although we differed from the contributor on the malignancy of the larger adrenocortical neoplasm. Conference participants were somewhat split, with the lack of nuclear atypia and well-demarcated nature of this neoplasm as helpful features supportive of an adenoma interpretation. Conference discussion also focused on whether lymphovascular invasion was present. We carefully reviewed the contributor’s supplied image and the accompanying feature of the case slide of a large cluster of adrenocortical cells within the lumen of a blood vessel. In line with Meuten et al,9 we felt that this was more likely to be pseudo-vascular invasion due to tissue sectioning and/or processing.

We performed a number of IHCs for this case to support these diagnoses with one surprise. Chromogranin and synaptophysin are both neuroendocrine markers that label pheochromocytomas, but are not specific per se as they do label other neuroendocrine and ganglion cell tumors. (It should be noted that pheochromocytoma is a specific form of paraganglioma, and all paragangliomas label for chromogranin and synaptophysin.)

Dr. Smedley graciously ran a met-enkephalin IHC at MSU for this case as both normal and neoplastic chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla should react strongly. In this case, both chromogranin and synaptophysin were strongly and diffusely immunoreactive within this smaller neoplasm as well as highlighting the remnant portion of the adrenal medulla. Curiously, met-enkephalin labeled the adrenal medulla, but not the neoplasm, an odd finding which was new to Dr. Smedley (we do not have this immunomarker available to us at the JPC). . Although we report this neoplasm as being consistent with a pheochromocytoma, we cannot exclude the remote possibility of a metastasis of a neuroendocrine tumor to the adrenal gland.

The nuclear features of this particular neoplasm display greater atypia and a higher mitotic rate than expected with most pheochromocytomas, so the the possibility of a “malignant pheochromocytoma” should be considered. Pheochromocytomas are generally termed "pheochromocytoma" when considered benign and "malignant pheochromocytoma" when considered malignant. Malignant pheochromocytomas are composed of small cells closely resembling chromaffin cells which are admixed with larger and more pleomorphic cells with a higher mitotic rate than those described in pheochromcytomas.5

References:

- Barthez PY, Marks SL, Woo J, et al. Pheochromocytoma in dogs: 61 cases (1984-1995). J Vet Intern Med. 1997;11:272–278.

- Bielinska M, Parviainen H, Kiiveri S, et al. Review paper: origin and molecular pathology of adrenocortical neoplasms. Vet Pathol. 2009;46:194–210.

- Gilson SD, Withrow SJ, Wheeler SL, et al. Pheochromocytoma in 50 dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 1994;8: 228–232.

- Goiska-Zygner O, Lechowski R, Wojciech Z. Functioning unilateral adrenocortical carcinoma in a dog. Can Vet J. 2012;53:623–625.

- Kiupel M. Histological Classification of Tumors of the Endocrine System of Domestic Animals, vol. 12. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 2008:44–47.

- Labelle P, Kyles AE, Farver TB, et al. Indicators of malignancy of canine adrenocortical tumors: histopathology and proliferation index. Vet Pathol. 2004;41:490–497.

- Machida T, Machida N. Invasion of pheochromocytoma from the caudal vena cava to the right ventricular cavity in a dog. Case Rep Vet Med. 2020; Feb 11;2020:5382687.doi: 10.1155/2020/5382687.

- Mauldin EA, Peters-Kennedy J. Integumentary system In: Maxie G, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer`s Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th Vol. 1. St. Louis: Elsevier, 2016:509–736.

- Meuten DJ, Moore FM, Donovan TA et al. International Guidelines for Veterinary Tumor Pathology: A Call to Action. Vet Pathol. 2021 Sep;58(5):766-794.

- Nabeta R, Osada H, Ogawa M, et al. Clinical and pathological features and outcome of bilateral incidental adrenocortical carcinomas in a dog. J Vet Med Sci. 2017;79: 1489–1493.

- Reusch CE, Feldman EC. Canine hyperadrenocorticism due to adrenocortical Pretreatment evaluation of 41 dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 1991;5: 3–10.

- Rosol T, Gröne A. Endocrine Glands. In: Maxie G, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmer`s Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th Vol. 3. St. Louis: Elsevier, 2016:326–428.

- Rosol TJ, Meuten. Tumors of the endocrine glands. In: Meuten DJ, ed., Tumors in Domestic Animals: 6th, Iowa: Wiley & Sons; 2016:766–833.

- Taylor J, Lee M, Nicholson M, et al. Functional ectopic adrenal carcinoma. Can Vet J. 2014; 55:845–848.

15. Zini E, Nolli S, Ferri F, et al. Pheochromocytoma in dogs undergoing adrenalectomy. Vet Pathol. 2019;56:358–368.