CASE II: PV406-20 (JPC 4162140)

Signalment:

Eight-year-old female spayed Border collie, canine.

History:

Alopecia and hyperpigmentation for a few months. Gradually presented with marked areas of alopecia of black skin. Negative for demodecosis. No response to antimycotic treatment for two weeks. Biopsies of skin from the leg and from the side of the mouth.

Gross Pathology:

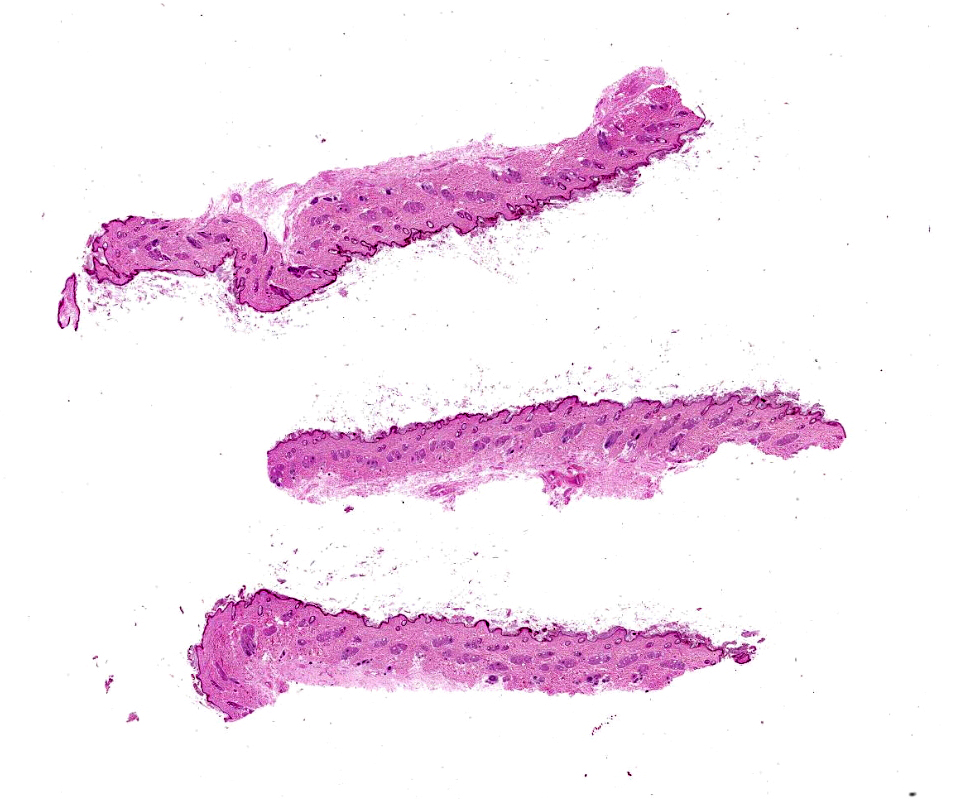

Wedge biopsies of skin.

Laboratory results:

No laboratory findings reported.

Microscopic Description:

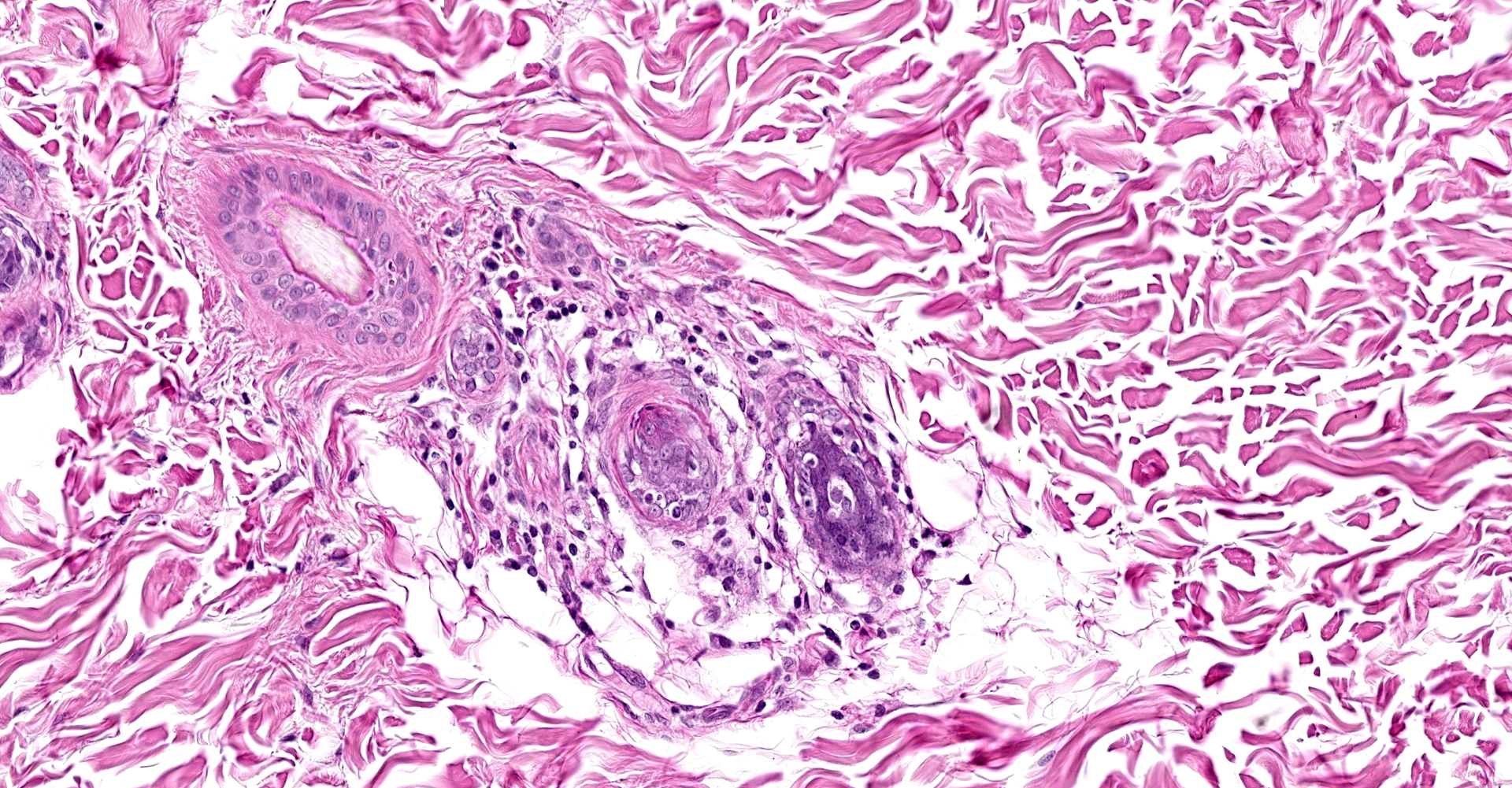

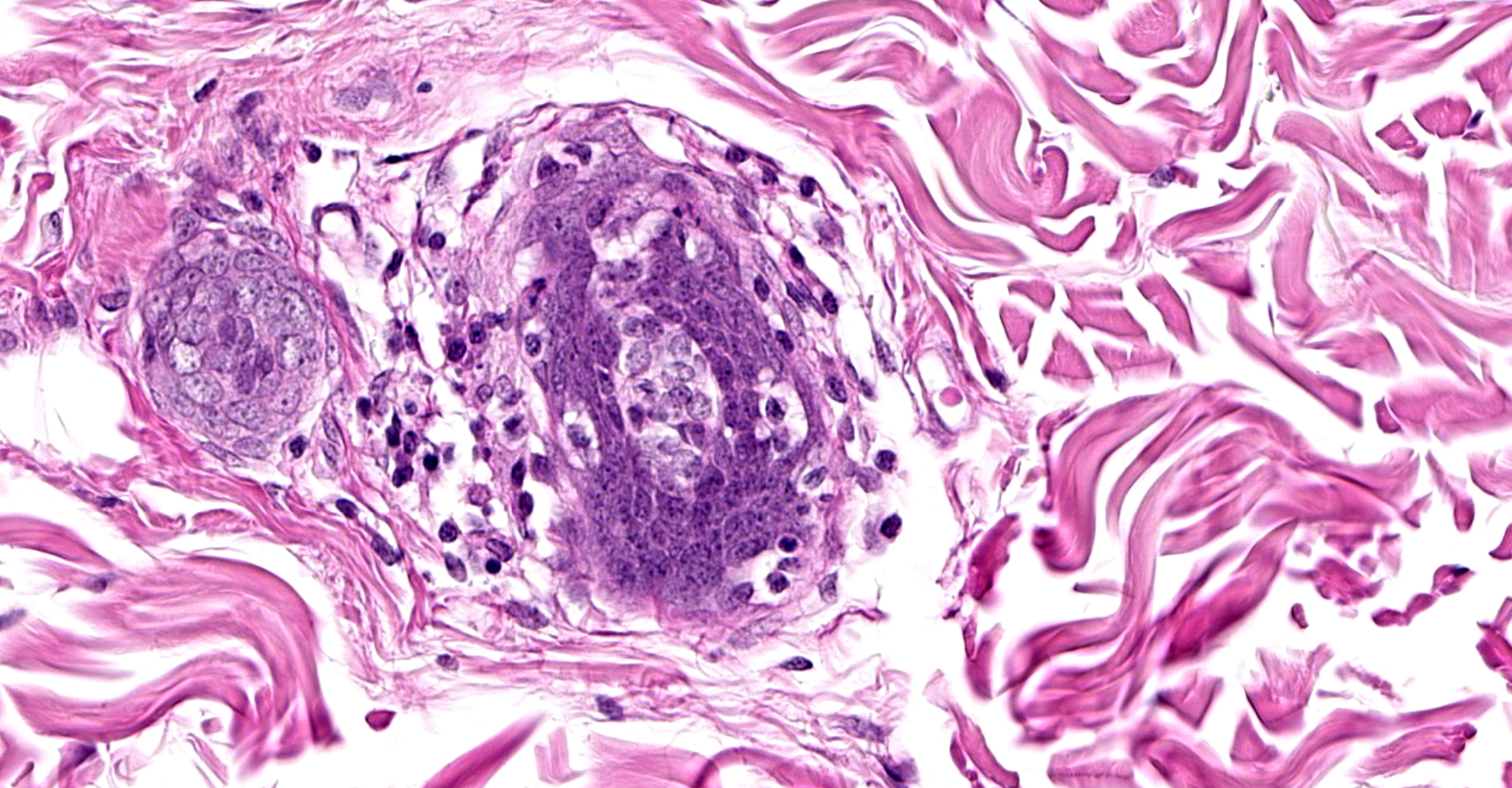

Serial sections of the skin samples submitted are evaluated. The epidermis appears to be thinner than normal. There is mild diffuse hyperkeratosis. Hair follicles are in all stages of growth. Small to moderate numbers of lymphocytes are forming aggregations around hair follicles, infiltrating anagen bulbs. There is occasional swelling of acanthocytes of the bulb epithelium and pyknosis of epithelial cells in occasional anagen bulbs.

Contributor's

Morphologic Diagnoses:

Lymphocytic

folliculitis (bulbitis), findings most compatible with alopecia areata.

Contributor's Comment:

Alopecia areata is uncommon in dogs and very rare in cats. It may be focal, multifocal or generalized (alopecia universalis). It is mostly characterized by well-defined patches of hair loss, usually non-scarring and non-inflammatory.2,3,4 The patches of alopecia most commonly present in the skin of the head or face. Legs may also be affected. Leukotrichia is occasionally observed. The areas of alopecia may become variably pigmented and may be bilaterally symmetrical. Occasionally, alopecia areata may be confined to the dark-haired areas of multicolored hair coats.3 There is no apparent age predilection and there are no studies on breed predisposition, but it is thought that German shepherds, dachshunds and beagles may be predisposed.4

In alopecia areata cycling is interrupted. It is believed that the lesions are caused by an immune-mediated mechanism directed against hair follicles in humans, nonhuman primates, dogs, cats, horses and cattle, which may be modulated by genetics and hormones.3,4 Environmental factors such as stress, vaccination, infection and diet may affect the development of the disease.4

The histological findings initially may present by accumulation of lymphocytes ("swarm of bees") in and around the inferior segment of anagen hair follicles. But more commonly subtle aggregations of lymphocytes, macrophages and even some plasma cells are observed around the inferior portion of the hair follicle (peribulbar).2 Occasionally neutrophils may be observed.4 Peribulbar mucin deposition and pigmentary incontinence may also be seen.4 Sebaceous glands are normal.2

Immunostaining to detect CD3+ and CD8+ lymphocytes may be helpful in some cases.

In chronic cases the histological findings consist of a predominance of catagen and telogen hair follicles as well as follicular atrophy.1 Therefore, early sampling and submission of multiple biopsies is strongly recommended for accurate diagnosis.4

Diagnosis is fairly straightforward if bulbitis is observed histologically. Differential diagnosis should include other syndromes with mural/isthmus folliculitis, such as pesudopelade, as in some severe cases, the lymphocytic infiltration of alopecia areata may progress towards the isthmus of the hair follicle, and isthmus and mural folliculitis of other syndromes may progress towards the bulb. It is important to note though, that in other syndromes, the follicular bulb is not affected.1

The differential diagnosis is of prognostic importance because hair loss in alopecia areata is usually transient. Alopecia in pseudopelade is usually permanent.

Reorientation and/or step sectioning of skin samples should be considered in cases where the clinical presentation is highly suspicious and subtle bulbitis can't be observed histologically.1,4

The prognosis for alopecia areata is good, with 60% of the cases having spontaneous and complete hair regrowth. However, sometimes the hair regrowth is white.1,2,3

Treatment with immunosuppressive doses of prednisone is often effective.3

Contributing Institution:

The Weizmann Institute of Science

JPC Diagnosis:

Haired skin, anagen follicles: Bulbitis, lymphocytic, multifocal, mild.

JPC Comment:

The contributor provides a concise review of alopecia areata, a condition that affects multiple species, including humans. In the United States, this condition affects 4.5 million people. Amongst the worldwide human population, the prevalence is up to 0.2% with a calculated lifetime risk of 2%. Although children are rarely affected, 66% of those affected are younger than 30 years of age and only 20% are older than 40 years of age. The condition is also associated with in increased risk of other autoimmune disorders, such as lupus erythematosus, vitiligo, and autoimmune thyroid disease.1

Normal hair growth occurs via a repetitive cyclic process. Healthy hair follicles transition from a period of very rapid growth, pigmentation, and hair-shaft production (anagen) to a short, apoptosis-driven phase of involution (catagen). Following catagen, hair follicles undergo a period of relative quiescence (telogen) before reentering anagen. This regenerative cycle is made possible by an abundance of keratinocyte and melanocyte stem cells predominantly located in the hair bulb. Hair follicle cycling and regeneration are stem-cell dependent and hair-shaft production and pigmentation are accomplished by differentiated progeny of these stem cells. These rapidly proliferating keratinocytes and pigment producing melanocytes reside in the anagen hair matrix, the primary target of inflammation in alopecia areata.1

A key feature of alopecia areata is inflammatory cells only attack anagen hair follicles, resulting in their premature reentry into the catagen phase. The hair shaft is rapidly shed from the follicle as a result of inflammation induced dystrophy. However, the follicle often retains the ability to regenerate and continue cycling since hair follicle stem cells are not usually lost, which is in contrast to other disorders that may result in scarring.1 Histologic sections obtained from chronic and clinically static cases often demonstrate predominately telogen follicles and follicular atrophy, which are non-diagnostic and may result in the misdiagnosis of an endocrine skin disorder.3

The pathogenesis of alopecia areata is not completely understood although it is presumably an autoimmune alopecic inflammatory disorder directed against hair follicles.2 Notably, several autoantigens associated with pigment production are immunogenic. One theory is alopecia areata occurs as the result of melanogenesis-associated autoantigens generated during active hair shaft pigmentation (in addition to other anagen associated hair follicle autoantigens) attracting autoreactive CD8+ T cells. Clinically, this theory is supported in that alopecia areata is occasionally confined areas of darkly pigmented hair. Under normal conditions, a key immunologic feature of the normal hair follicle is its creation of an environment of relative immune privilege, suppressing an autoimmune attack on intrafollicularly expressed autoantigens. This relative site of immune privilege results primarily from the suppression of surface molecules required for presenting autoantigens to CD8+ T lymphocytes (i.e. MHC class Ia antigens). Notably, the down-regulation of MHC class I molecules increases the risk of the hair follicle being attacked by natural killer (NK) cells, as these are primed to recognize and eliminate MHC class I negative cells. However, healthy hair follicles also counter this process by down regulating ligands that stimulate the activation of NK cell receptors (NKG2D) while also secreting molecules that inhibit NK cell and T cell functions, such as transforming growth factors β1 and β2, α melanocyte?stimulating hormone, and macrophage migration inhibitory factor.1

The moderator discussed the advantage of using immunohistochemical stains to aid in the diagnosis of alopecia areata, particularly in regard to the identification of CD3 positive lymphocytes within the hair bulb, which was observed in this case. Although CD79a lymphocytes were also observed, these cells were present within the adjacent perifollicular dermis, not within the follicular epithelium.

References:

1. Gilhar A, Etzioni A, Paus R. Alopecia areata. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(16):1515-1525.

2. Gross, T.L. et al. Mural diseases of the hair follicle. In: Skin diseases of the dog and cat, 2nd edition; Blackwell publishing. 2005:460-464.

3. Mauldin EA, Peters-Kennedy J. Integumentary system. In: Maxie MG ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 1. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Ltd. 2016:614-615.

4. Miller, W.H. et al. Autoimmune and immune-mediated dermatoses. In: Muller & Kirk's Small animal dermatology; 7th edition. Elsevier. 2013:462-463.