Signalment:

Gross Description:

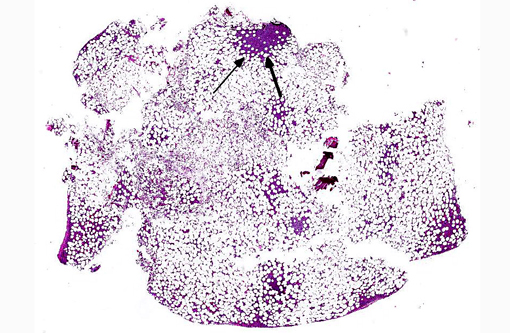

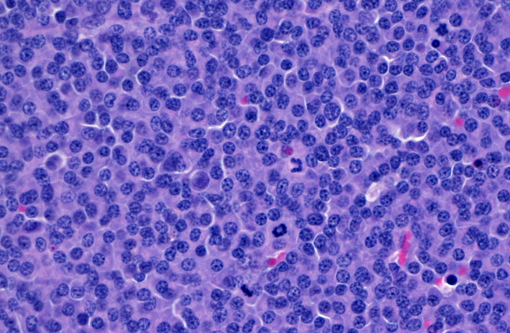

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

| Tests | Results | Reference Range | Units |

| Total Protein | 10.7 (HIGH) | 5.2-8.8 | g/dL |

| Globulin | 7.4 (HIGH) | 2.3-5.3 | g/dL |

| AST | 152 (HIGH) | 10-100 | U/L |

| AST (ALT?) | 155 (HIGH) | 10-100 | U/L |

| Urea Nitrogen | 52 (HIGH) | 14-36 | mg/dL |

| Creatinine | 2.6 (HIGH) | 0.6-2.4 | mg/dL |

| CPK | 1109 (HIGH) | 56-529 | U/L |

| Calcium, ionized | 2.20 (HIGH) | 1.16-1.34 | μmol/L |

| Calcium (verified) | 18.3 (HIGH) | 8.2-10.8 | mg/dL |

| Protein Electrophoresis, serum | |||

| Total Protein | 10.7 (HIGH) | 5.2-8.8 | g/dL |

| Gamma | 4.83 (HIGH) | 0.50-1.90 | g/dL |

| PTHrP | 0.0 | Less than 1.0 | pmol/L |

| PTH | 4.0 | 4-25 | pg/ml |

- CBC: WNL

- Platelet count: 56 (LOW); due to platelet clumping.

- Urinalysis (cystocentesis): Light yellow, clear, SG 1.038, pH 6.0, proteinuria (3+), hematuria (3+) and >50 RBC. Glucose, ketone, bilirubin were negative. No casts, crystals or bacteria. WBC and squamous epithelial cells were WNL.

- Urine microalbumin (feline): 7.4 (HIGH) indicating microalbuminuria.

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

In animals, multiple myeloma is a rare, malignant tumor that arises in the bone marrow. It has a slowly progressive clinical course and sites of metastasis include the spleen, liver, lymph nodes and kidneys. Though rare, it has been reported in horses, cattle, cats and pigs, but it is seen more frequently in older dogs with a mean age of 8-9 years.(1,12) In cats, the median age is 12-14 years and there is possibly a male predisposition.(2,6-8) The cause in domestic animals is unknown, but in people, plasma cell neoplasms are associated with working in agriculture, exposure to petroleum products, and chronic exposure to an antigenic stimulus.(3,9-11) There is no evidence that feline immunodeficiency virus, feline leukemia virus, or feline infectious peritonitis virus infections are related to the development of multiple myeloma in cats.(7)

Neoplastic plasma cells usually secrete large amounts of immunoglobulin (Ig), and the hallmark laboratory finding is hyperglobulinemia. This homogeneous protein fraction is often called paraprotein or M-protein.(5)

Diagnosis of multiple myeloma is based on a minimum of two of the following abnormalities:(1,4-6,12-13)

- Marked increase in numbers of plasma cells in the bone marrow (at least 30% of the nucleated cells are plasma cells which may be well differentiated to poorly differentiated cells with visible nucleoli, marked anisokaryosis and anisocytosis and multinucleation).

- Monoclonal gammopathy because of clonal production of Ig or Ig fragments by the neoplastic cells. This is demonstrated by serum electrophoresis and can be characterized further using immunodiagnostic techniques. Most of the Igs migrate in the gamma-region, but some may migrate to the beta-region (particularly IgA and IgM), hence the usage of the term monoclonal gammopathy. Note that monoclonal gammapathy is not specific to multiple myeloma and has been reported in cases of B lymphocyte lymphoma and some nonneoplastic conditions such as canine ehrlichiosis or leishmaniasis.Â

- Radiographic evidence of osteolysis.

- Light-chain proteinuria: Bence Jones proteins are free Ig light chains of low molecular weight that pass through the glomerular filter in the urine. These proteins do not react with urine dipstick protein indicators and are specifically detected by electroelectrophoresis and immunoprecipitation.

1) hypercalcemia, due to neoplastic cell production of osteoclastic-activating factors (RANKL) resulting in resorption of bone,

2) hemorrhage that is caused by secondary platelet dysfunction due to the binding of the paraprotein to platelets (decreased aggregation),

3) hyperviscosity syndrome (IgM and IgA dimers cause an increased viscosity of blood resulting in tissue ischemia and hemorrhage),

4) cytopenias caused by high numbers of neoplastic cells displacing normal bone marrow elements, and

5) renal disease, which develops from nephrocalcinosis secondary to chronic hypercalcemia, hypoxic damage from hyperviscosity, renal toxicity of light chains and neoplastic cell infiltration into the kidney and/or renal amyloidosis.Â

In this rare feline case of multiple myeloma, the diagnosis was made based on the hallmark laboratory finding of hyperglobulinemia and having two out of the four abnormalities for multiple myeloma: marked increase in numbers of plasma cells in the bone marrow and monoclonal gammopathy. In addition, there was metastasis to the spleen, kidney and liver. Hyperparathyroidism was ruled out based on PTHrP and PTH laboratory findings within normal limits.Â

Acknowledgement: The author thanks Dr. Lynn Facemire for contributing the clinical case history and the tissue samples for histopathology.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

References:

2. Hanna F. Multiple myelomas in cats. J Feline Med Surg. 2005;7(5):275-287.

3. Imahori S, Moore GE. Multiple myeloma and prolonged stimulation of reticuloendothelial system. NY State J Med. 1972;72(12):1625-1628.

4. Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster JC. Diseases of white blood cells, lymph nodes, spleen and thymus. In: Kumar V, Abbas AK, Fausto N, Aster JC, eds. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2009:609-610.

5. Latimer KS. Hematopoietic neoplasia. In: Latimer KS, ed. Duncan and Prasses Veterinary Laboratory Medicine Clinical Pathology. 5th ed. Ames, IA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011:93-95,173-181.

6. Mellor PJ, Haugland S, Smith KC, et al. Histopathologic, immunohistochemical, and cytologic analysis of feline myeloma-related disorders: further evidence for primary extramedullary development in the cat. Vet Pathol. 2008;45(2):159-173.

7. Mellor PJ, Haugland S, Murphy S, et al. Myeloma-related disorders in cats commonly present as extramedullary neoplasms in contrast to myeloma in human patients: 24 cases with clinical follow-up. J Vet Intern Med. 2006;20(6):1376-1383.

8. Patel RT, Caceres A, French AF, et al. Multiple myeloma in 16 cats: a retrospective study. Vet Clin Pathol. 2005;34(4):341-352.

9. Penny R. Hughes S. Repeated stimulation of the reticuloendothelial system and the development of plasma-cell dyscrasia. Lancet. 1970;1(7637):77-78.

10. Rosenblatt J, Hall CA. Plasma-cell dyscrasia following prolonged stimulation of reticuloendothelial system. Lancet. 1970;1(7641):301-302.

11. Speer SA, Semenza JC, Kurosaki T, et al. Risk factors for acute myeloid leukemia and multiple myeloma: a combination of GIS and case control studies. J Environ Health. 2002;64(7):9-16.

12. Valli VE. Hematopoietic system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol. 3. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Ltd; 2007:107-324.

13. Valli VE, Jacobs RM, Parodi AL, Vernau W, Moore PF. Histological Classification of Hematopoietic Tumors of Domestic Animals. 2nd Series, Vol. VIII. Washington DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 2002.