Wednesday Slide Conference, Conference 20, Case 3

Signalment:

11-year-old, female cockatiel (Nimphicus hollandicus).

History:

This cockatiel was first obtained by the owner in September 2019, approximately 5 months prior to euthanasia. Initial veterinary consultation was sought with the complaint of frequent trembling and shaking. Diagnostic evaluation was initially declined, except for Chlamydophila testing pursued at a different clinic (unspecified), which was reported as negative. At subsequent presentation to the submitting veterinarian, the bird was thin (66 g) could barely perch, and seemed painful, with wings drooped forward. On manipulation, the wings were stiff and could not be returned to normal anatomical resting position. Euthanasia was elected.

Gross Pathology:

Examined is the body of a female, 11-month-old, 60 g, Cockatiel with a body condition score of 2 out of 5 (North Carolina Zoo Keel Score) and moderate autolysis. No significant lesions were noted.

Microscopic Description:

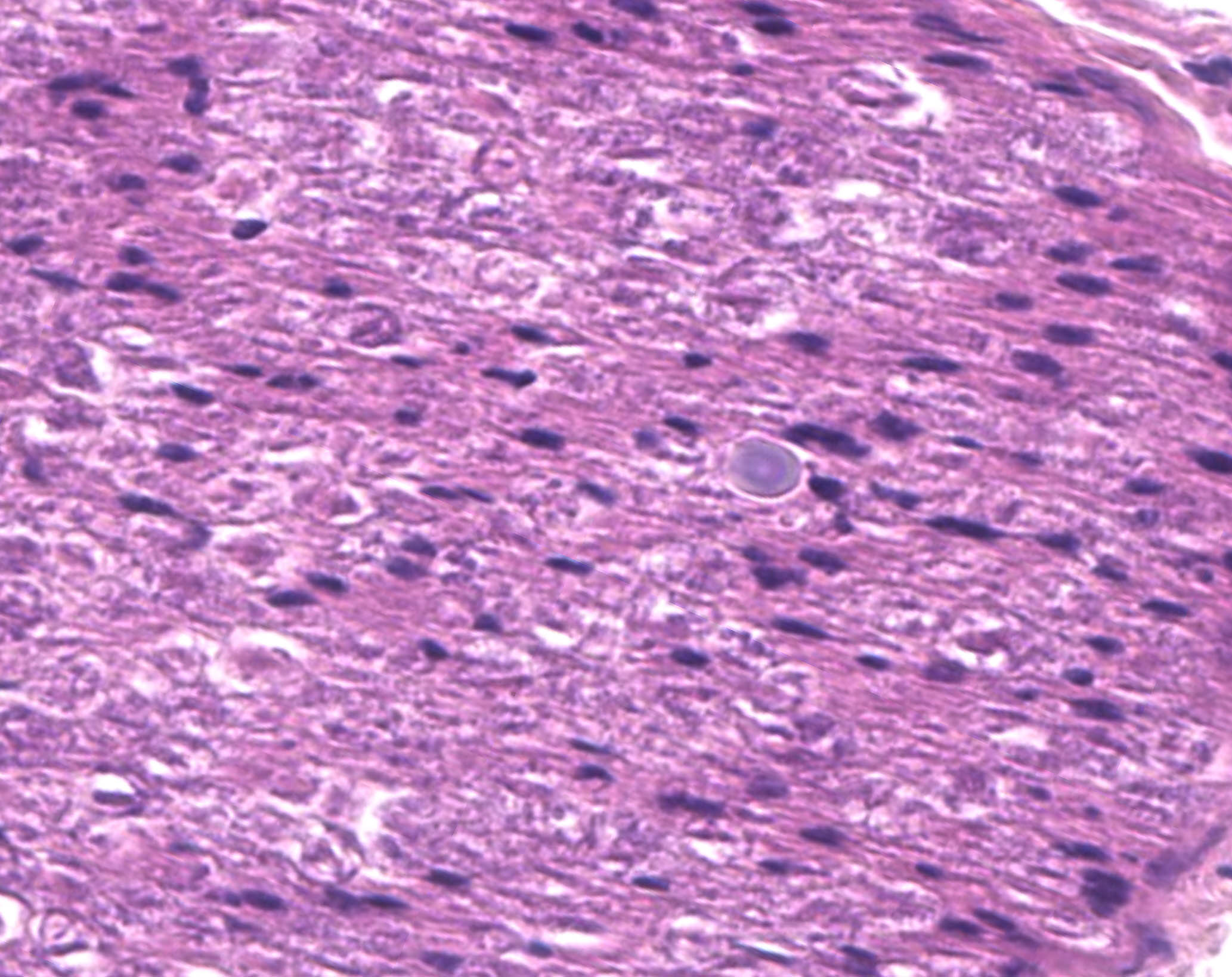

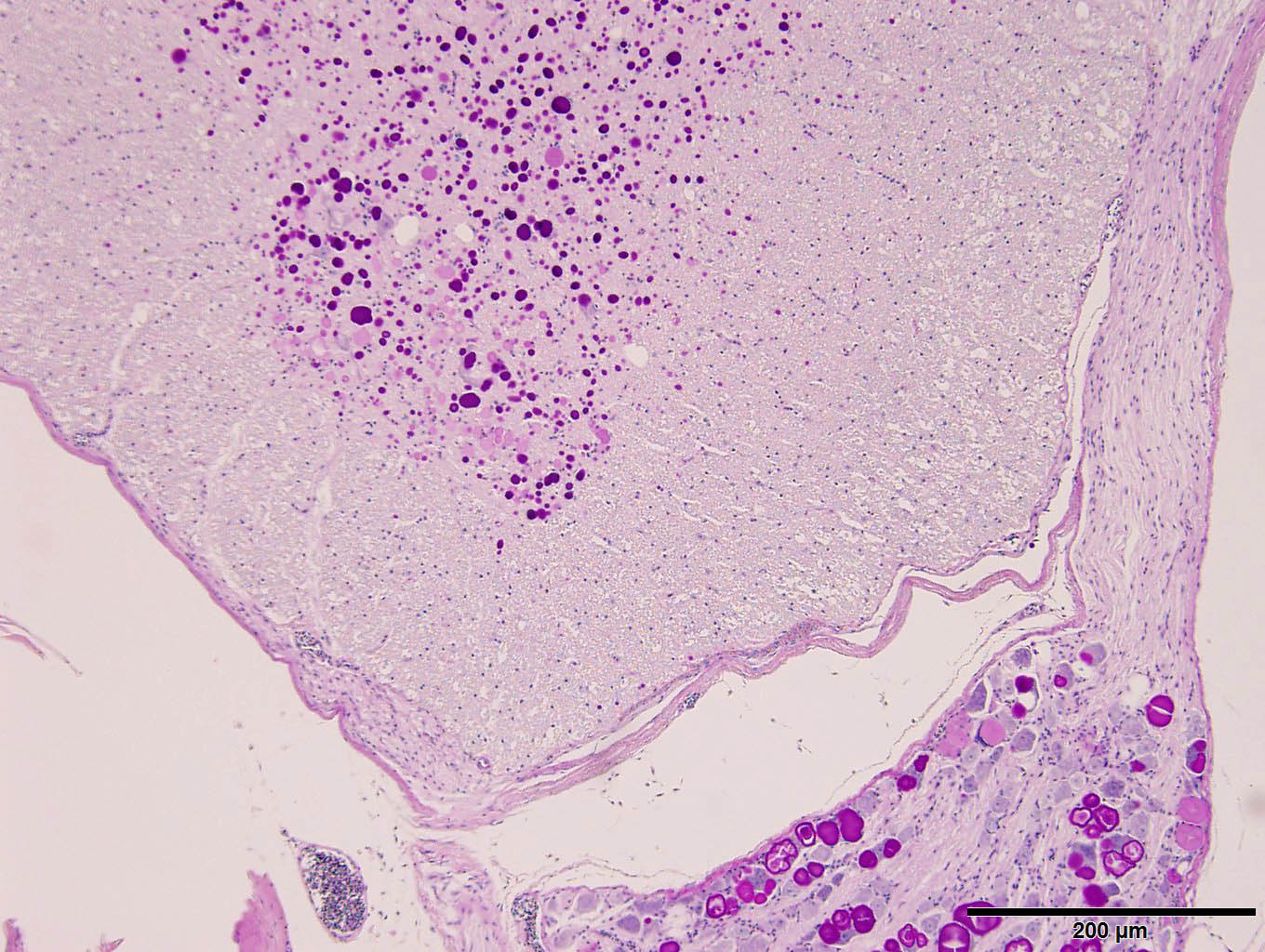

Examined are ten cross-sections of spinal column. Throughout all sections of the spinal cord, including cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and sacral regions, virtually all neurons within the gray matter and in the dorsal root ganglia contain large, intracytoplasmic, lamellar to globular, 5-35 µm in diameter, basophilic to eosinophilic structures. These intracytoplasmic structures often have a central, finely granular, pale center (Lafora bodies). Consistently surrounding the structures is a 2-5 µm wide band of finely granular, amphophilic cytoplasm (peripheral lysed axoplasm). Affecting approximately 20% of the axial muscles, muscle fibers are shrunken in multifocal random areas. Affected fibers have hypereosinophilic sarcoplasm with poorly defined cross striations and enlarged nuclei with open chromatin.

Period acid-Schiff staining with and without diastase applied to formalin-fixed, decalcified (formalin/formic acid solution), paraffin-embedded spinal column tissue highlights intensely PAS-positive, 5-35 µm intraneuronal cytoplasmic inclusions which are resistant to diastase digestion.

Staining of the same tissue using Luxol fast blue with cresyl violet and Acian blue (pH2.5) reveals bright violet and deep blue staining of the described inclusions, respectively.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Spinal cord: Numerous polyglucosan bodies consistent with Lafora disease

Contributor’s Comment:

Lafora disease (neuronal glycoproteinosis) is a rare condition variably characterized by myoclonus, ataxia, weakness, behavioral abnormalities, and seizures in affected animals.1,3-6,9,10 These clinical signs result from abnormal carbohydrate metabolism and accumulation within the perikaryon, dendrites, and axons of neurons as well as freely in the neuroparenchyma of both central and peripheral nervous tissue.2 Inclusion bodies can also be found in other organ systems including skeletal and cardiac muscle, skin, and liver. In this case, inclusions were present in the cerebrum, spinal cord, dorsal root ganglia, perirenal ganglia, and myenteric ganglia.

These inclusion bodies, also called Lafora bodies, are spherical, basophilic, 5-35 µm, PAS-positive and diastase-resistant, and also display staining with Cresyl violet, Alcian blue pH 2.5, Bests carmine, methenamine silver, and Weils (6). Lafora bodies are composed of polyglucosan, an abnormal form of glycogen with low numbers of branches and very long glucose chains.8 On electron microscopy, Lafora bodies are composed of radiating, branched filaments surrounding a dense central core.9

Disease associated with Lafora body accumulation has been described in humans, dogs, cockatiels, cattle, a fox, a cat, and a flying fox,1,3-6,8,9 with associated genetic mutations identified in humans, miniature wirehaired dachshunds, a basset hound, and beagles.4,7 In humans, Lafora disease is a fatal autosomal-recessive condition resulting from loss of function sequence variations in the genes EPM2A (encodeing laforin) or NHLRC1 (also EMP2B, encodes malin),4 encoding glycogen synthesis regulators laforin and malin, and the latter of which has also been implicated in dogs with a massive expansion of a 12 bp repeat in the gene.4.7

Contributing Institution:

Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Biomedical Sciences, Section of Anatomic Pathology

https://www.vet.cornell.edu/departments/biomedical-sciences/section-anatomic-pathology

JPC Diagnosis:

- Spinal cord, spinal nerves, dorsal root ganglion: Intracytoplasmic polyglucosan (Lafora) bodies, numerous, with mild spongiosis

- Spinal muscles: Atrophy, multifocal, mild

JPC Comment:

We have seen Lafora disease several times in conference, to include in an ox (WSC 2017-2018, Conference 17, Case 4) and in multiple dogs (WSC 2021-2022, Conference 7, Case 3; WSC 2012-2013, Conference 22, Case 4). The present case in a bird is interesting, though as the contributor notes this condition has previously been described in a cockatiel.1 There is also a recent case report in a toucan from Brazil with features that mirror this case.11

Inclusion bodies were numerous across the provided sections of spinal cord and spinal nerves and stained readily with PAS, Alcian blue, and Luxol fast blue. We considered whether these inclusions might also be similarly present within skeletal muscle given that select myocytes also contain amphophilic globoid material. However, these myocyte inclusions did not reliably stain with PAS or Alcian blue (or at all with LFB), so we were unable to confirm this impression. As these stains are non-specific, it is possible that inclusions in myocytes may represent an entirely different material.

We added a separate morphologic diagnosis of muscular (neurogenic) atrophy that corresponds to the decreased body condition and inability of this animal to perch. This is best observed from subgross as shrunken, condensed myofibers. Additionally, there is also medullary bone (i.e., endostosis) present which is a normal/expected finding for a mature female bird. This amphophilic to basophilic bone is deposited on the outer aspects of the medullary trabeculae and represents a dynamic calcium depot for the egg-laying cycle. Medullary bone has also been described as a premonitory sign of testicular neoplasms in male birds.12

References:

- Britt JO, Paster MB, Gonzales C. Lafora Body Neuropathy in a Cockatiel. Comp Anim Pract 19:31–33, 1989.

- Cantile C, Youssef S. Nervous system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer’s Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. Vol 1. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016: 255, 292.

- Gabor LJ, Srivastava M. Polyglucosan Inclusions (Lafora Bodies) in a Gray-Headed Flying Fox (Pteropus Poliocephalus). J Vet Diagn Invest. 22:303–304, 2010.

- Hajek I, Kettner F, Simerdova V, et al. NHLRC1 repeat expansion in two beagles with Lafora disease. J Small Ani Pract 2016; 57:650–652.

- Hall DG, Steffens WL, Lassiter L. Lafora Bodies Associated with Neurologic Signs in a Cat. Vet Pathol 35:218–220, 1998.

- Honnold SP, Schulman FY, Bauman K, Nelson K. Lafora’s-Like Disease in a Fennec Fox (Vulpes zerda). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine. 2010; 41:530–534.

- Lohi H, Young EJ, Fitzmaurice SN, et al. Expanded Repeat in Canine Epilepsy. Science 307:81–81, 2005.

- Serratosa JM, Minassian BA, Ganesh S. Progressive Myoclonus Epilepsy of Lafora. In: Noebels J, Avoli M, Rogawski M, Olsen R, Delgado-Escueta A, eds. Jasper’s Basic Mechanisms of the Epilepsies. Oxford University Press; 2012:874–877.

- Simmons MM. Lafora Disease in the Cow? J Comp Path 110:389–401, 1994.

- Swain L, Key G, Tauro A, et al. Lafora disease in miniature Wirehaired Dachshunds. PLOS ONE 12:e0182024, 2017.

- Santana CH, et al. Lafora’s disease in a free-ranging toco toucan (Ramphastos toco) with neurologic disease. Brazilian J Vet Path. 2023; 16(2):144-147.

- Hoggard NK, Craig LE. Medullary bone in male budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulatus) with testicular neoplasms. Vet Pathol. 2022 Mar;59(2):333-339.