Signalment:

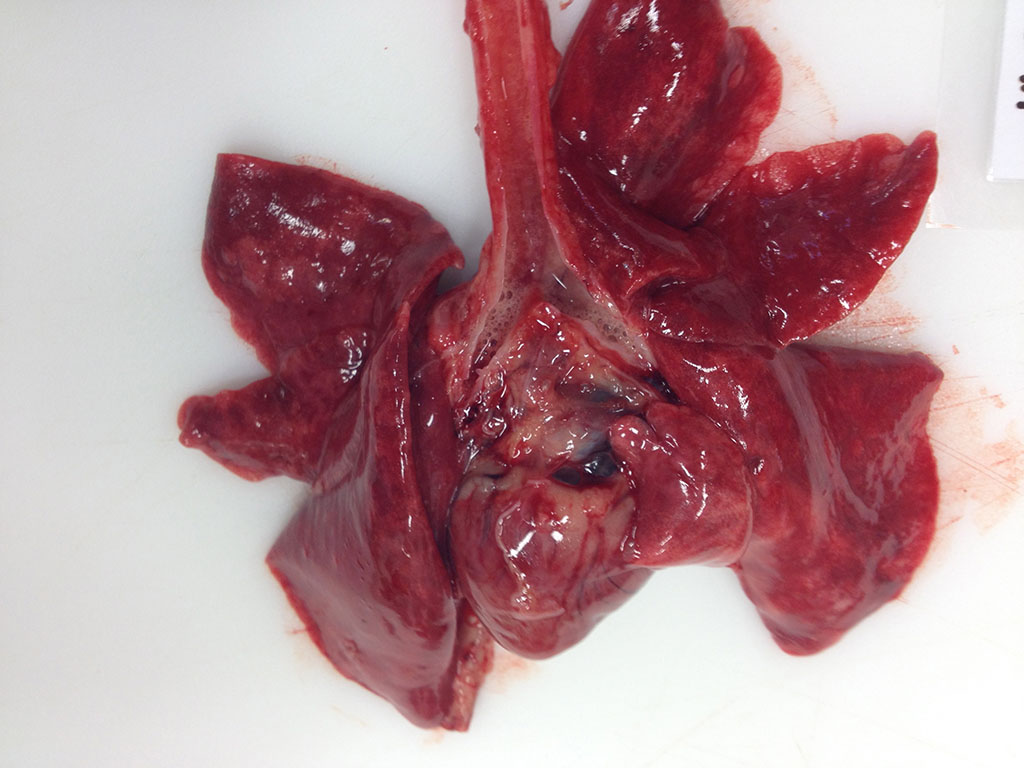

Gross Description:

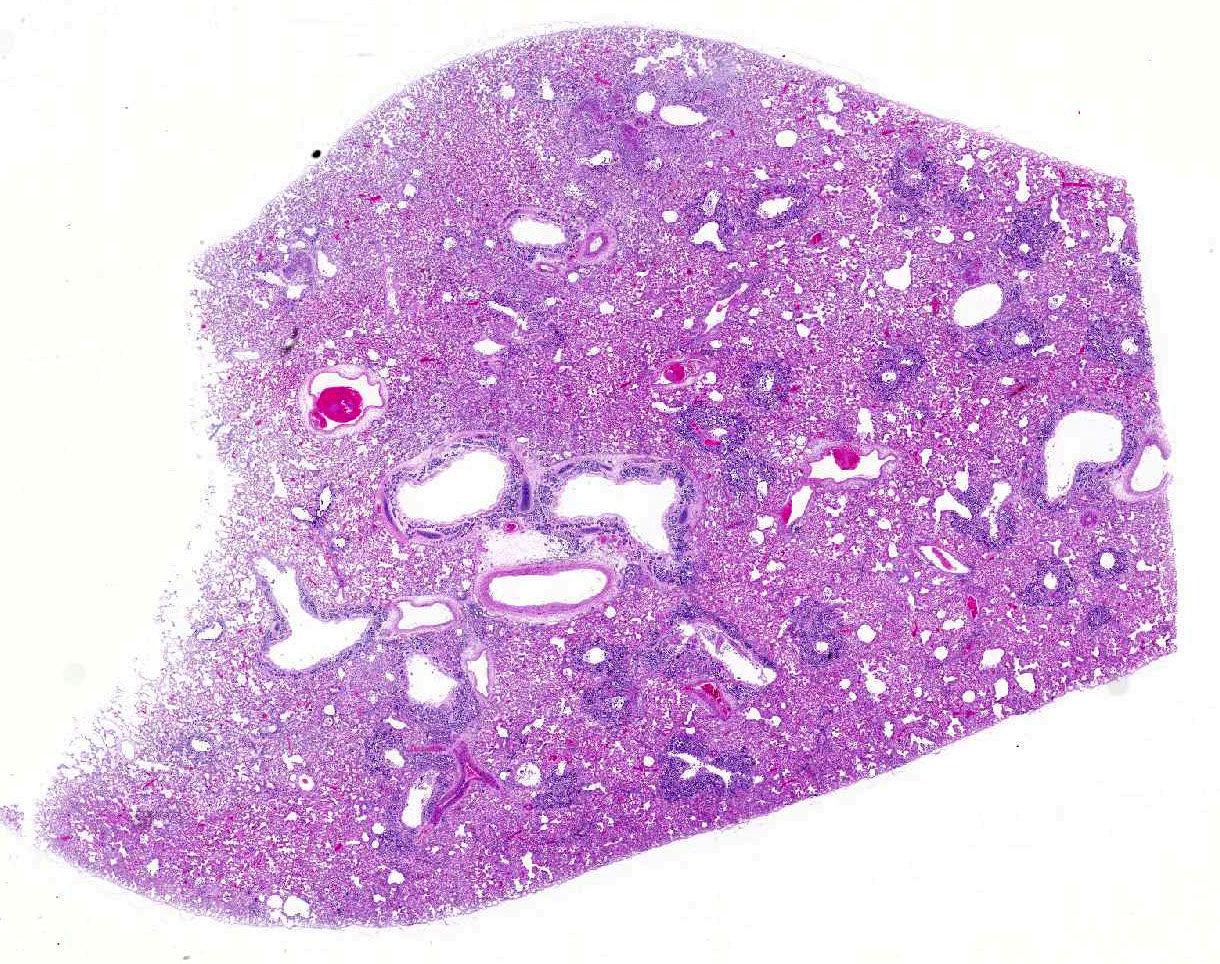

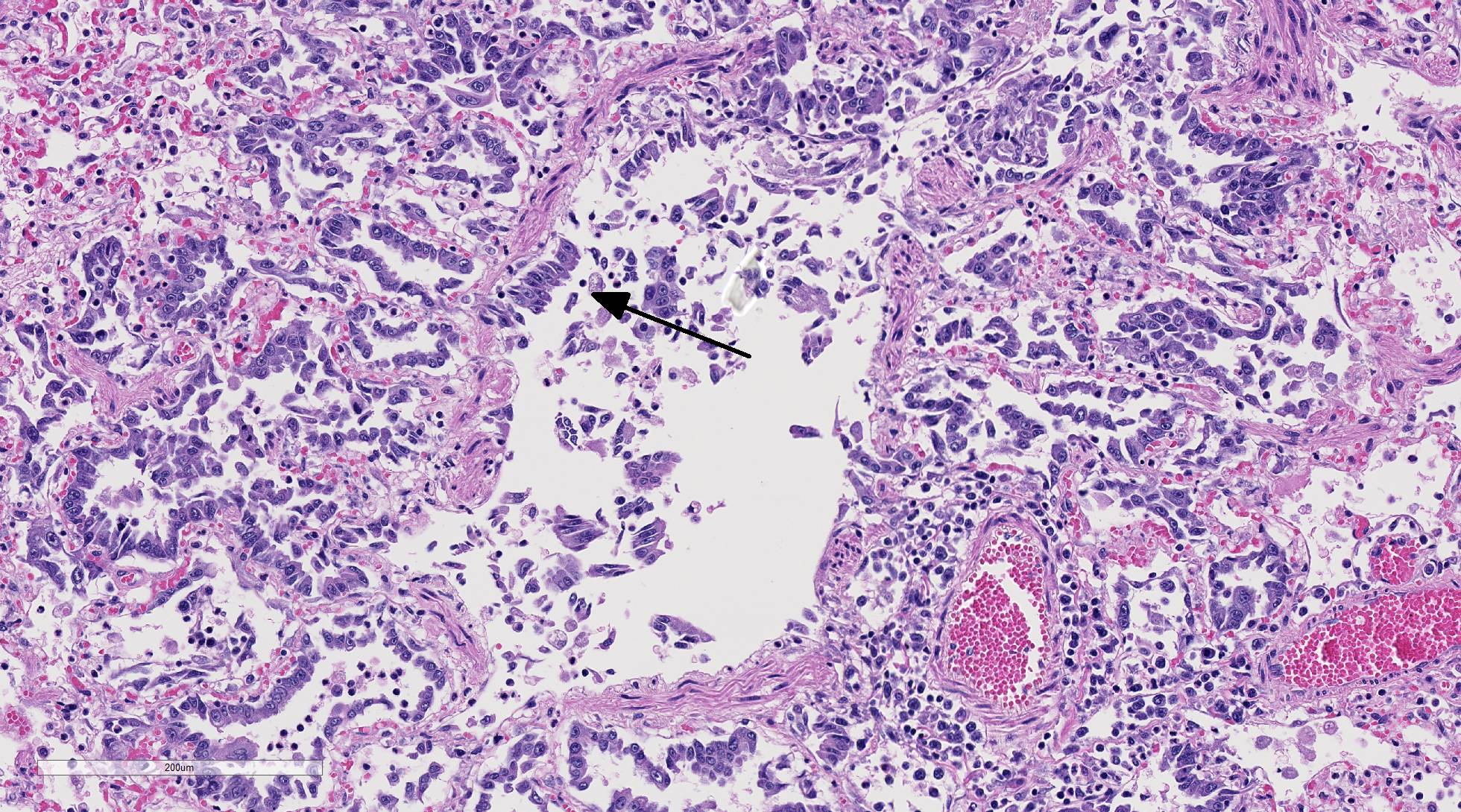

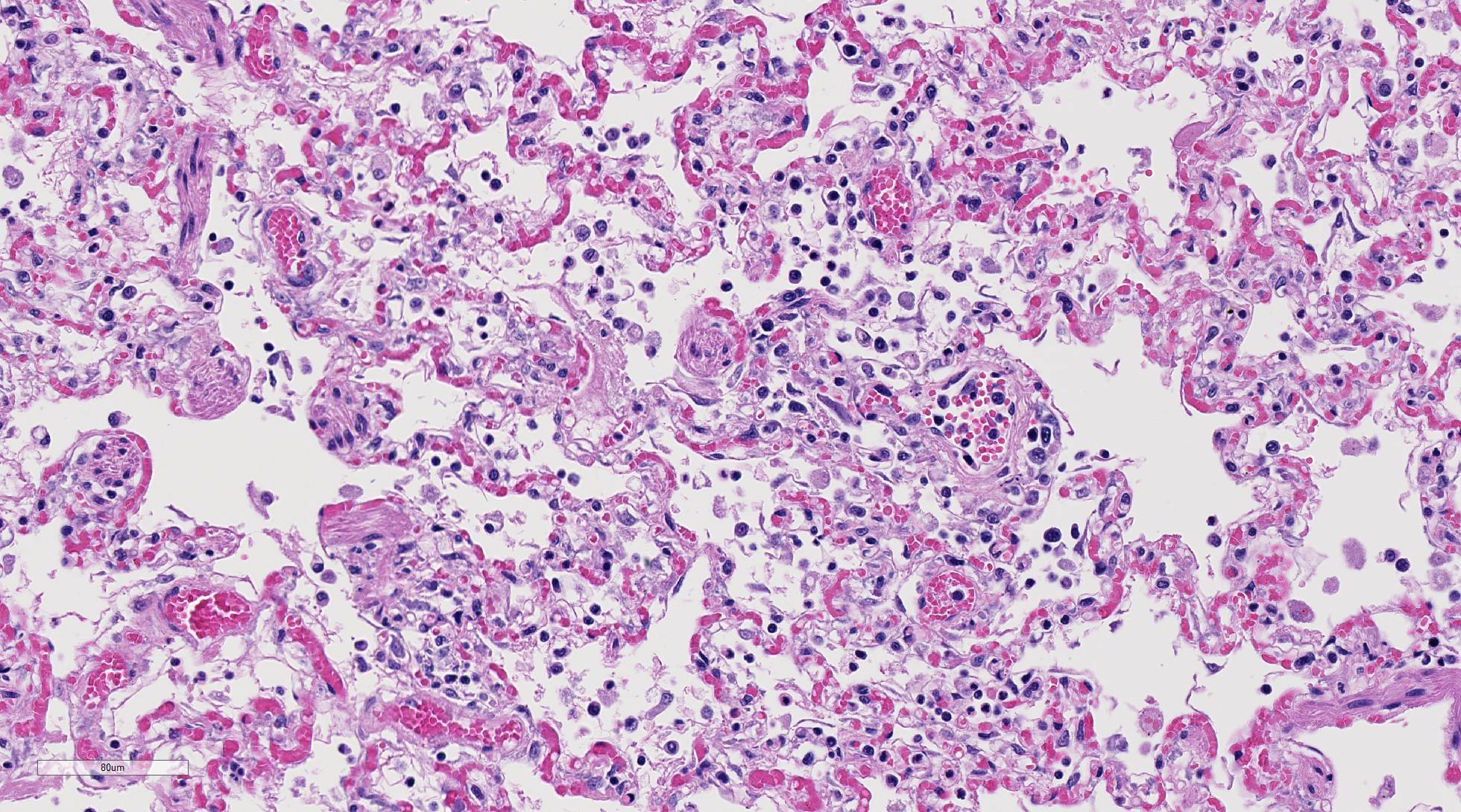

Histopathologic Description:

Diffusely, alveolar airspaces contain moderate numbers of cells, predominantly macrophages and lymphocytes, with fewer non-degenerate neutrophils and red blood cells. In addition, alveolar airspaces contain abundant eosinophilic beaded to fibrillar material (fibrin). Numerous peribronchiolar alveoli are lined by markedly hypertrophied cuboidal epithelial cells with large nuclei and prominent nucleoli (type II pneumocyte hyperplasia). Multinucleate pneumocytes are occasionally seen.

Around larger pulmonary vessels, connective tissue is moderately expanded by clear space (perivascular edema). Throughout all sections, muscular pulmonary arteries and arterioles have moderately thickened walls (smooth muscle hyperplasia).

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Influenza A viruses are RNA viruses in the family Orthomyxoviridae that can infect multiple species of mammals and birds, although different viral subtypes tend to be host-specific.17 These viruses have caused multiple epidemics and pandemics in human populations,11 as well as epizootics and panzootics in animal species.12,16 Rapid mutation and gene reassortment of influenza A viruses lead to a high diversity of viral subtypes, and this genetic flexibility results in a propensity for between-species and cross-class transmission.18 The so-called pandemic strain of the H1N1 influenza virus isolated in 2009 (influenza A(H1N1)pdm09) contained a novel combination of genetic segments from influenza viruses affecting humans, pigs, and birds.6

Cats are susceptible to infection by multiple influenza A virus subtypes;1 however, reports of clinical disease in cats resulting from natural infection with A(H1N1)pdm09 are relatively scarce.3,5,8,10,13 The source of this particular cats infection could not be determined. The owner lived alone, had received a seasonal influenza vaccination in October of 2013, and had never become sick. However, she had hosted two house guests for a three day period after Christmas 2013, approximately 10 days before the deaths of her two cats in early January, 2014. One guest had flu-like symptoms and remained indoors for the majority of the visit. Although the cause of this guests illness was never known, the 20132014 influenza season was intensive in Alberta; there were 35% more lab-confirmed cases of human influenza infection than the previous year and the predominant circulating strain was influenza A(H1N1)pdm09.14 Thus, the sick guest could not be ruled out as the source of this cats, and/or her littermates, infection.

The possibility of anthroponotic transmission of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 to cats is supported by two earlier reports. The first describes an indoor-only cat that was infected with influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 after exposure to human family members with a non-diagnosed flu-like illness.13 The second shows that pet cats are nearly three times more likely to be seropositive for influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 than free-roaming cats.18 Cat-to-cat transmission of influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 has also been documented, both experimentally15 and in an outbreak in cats with little human contact living in a cat colony in Italy.5 Zoonotic transmission of influenza viruses from cats to humans may also occur, and the role that cats may play in the epidemiology of human influenza infections needs further investigation.1

The cat described here died from severe pneumonia caused by pandemic influenza A virus infection. This virus was not detected in samples sent to a commercial laboratory, but was detected in samples sent to a second laboratory. Therefore, if clinical signs, history (exposure to people or animals infected with influenza virus), gross lesions, and histologic findings are suggestive of influenza virus infection, it is reasonable to test samples in a second laboratory should a first laboratory provide a negative result for influenza virus infection. This case highlights the importance of including influenza virus infection in the differential diagnosis for respiratory disease in cats. It also further demonstrates the importance of investigating any discrepancy between histologic findings and expected laboratory results.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

The conference moderator also noted that in this case the virus appears to exhibit a tropism for terminal airways with relative sparing of the larger bronchi. The specific anatomic location of lesions associated with influenza virus has been reported to correlate with the distribution of sialic acid molecules on the cell surface of the host.8,9 In human pandemic H1N1 influenza A, these sialic acids are distributed in the trachea and larger airways, resulting in necrotizing tracheitis and bronchitis in severely affected human patients. In pathogenic avian influenza H5N1, the virus binds to sialic acids present mainly on terminal bronchioles and pneumocytes.8,9 Interestingly, the distribution of lesions in this case differs from the typical presentation of human H1N1 influenza A, and resembles binding of avian influenza viral particles. This distribution pattern has been reported in other cases of H1N1 infection in cats.8

Influenza viruses are RNA viruses of the Orthomyxovridiae family, and are able to rapidly mutate through antigenic drift and genetic reassortment.1,7,8,9 This leads to a high degree of viral diversity and genetic flexibility, thus allowing the virus to quickly adapt and infect multiple different species.7,8 In addition to human origin H1N1, presented in this case, cats are also susceptible to highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 and H7N2 viruses.4 Cats have been reported to be infected with H1N1 by interaction with infected humans, as is suspected in this case, and then transmit the disease horizontally to other felids. There are currently no reports of transmission from cat to human with H1N1 virus.7,8 Infection with highly pathogenic avian influenza in cats is thought to be secondary to both inhalation of aerosolized virus and consumption of infected birds.4

In December 2016, there was an outbreak of H7N2 avian influenza in almost 400 shelter cats in New York City.2 A shelter veterinarian who had prolonged and unprotected exposure to affected cats was also infected with the virus. This is the first documented case of cat to human transmission of influenza and only the third case of human H7N2 avian influenza infection in the United States.2 Given their close relationship with humans and susceptibility to both human and avian influenza strains, cats have the potential to be important reservoirs for infection.2,7,8 Feline co-infection with human and avian strains may allow genetic reassortment and antigenic shift creating a novel influenza A subtype and provide the basis for a new influenza pandemic.7 As a result, influenza virus should be carefully considered as a differential diagnosis for respiratory disease in cats.

References: