Signalment:

Gross Description:

In the abdominal cavity renal lipidosis and hyperhaemia of most organs was evident.Â

In the thoracic cavity severe pulmonary edema and severe constrictive cardiomyopathy were present

Histopathologic Description:

The epidermis is hyperkeratotic, irregularly hyperplastic and occasionally characterized by infiltration of plasmacells. Superficial erosion or serocellular crusting characterizes some of the sections.Â

Additional microscopic findings:

Hepatic lipidosis, diffuse membranous glomerulonephritis, renal tubular hyaline casts and diffuse tubular lipidosis.Â

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

The cause and pathogenesis of feline plasmacytic pododermatitis are still unknown however, the marked plasma cell infiltrate, consistent hypergammaglobulinemia and response to immunosuppressive (i. e. glucocorticoids) or immunomodulating (i. e. tetracyclines) therapy suggest an immune dysfunction(7,11). In some cats concurrent plasmacytic stomatitis, renal amyloidosis or immune-mediated glomerulonephritis have been reported .In some cases, spontaneous remission of the lesions occurs, whereas in others there is a seasonal exacerbation of the disease. Recurrence in warm weather may support an allergic origin. Doxycycline monohydrate has been reported to produce partial or complete clinical remission in more than half of the cases (1). The response of feline plasma cell pododermatitis to doxycycline is possibly due to its immunomodulatory effects, but since doxycycline has also antibacterial activity an infectious etiology has also been suggested. In a recent study, no infectious agent has been demonstrated by anti-BCG immunohistochemistry and by PCR assays for Bartonella spp., Ehrlichia spp., Anaplasma phagocytophilum, Chlamydophila felis, Mycoplasma spp., Toxoplasma gondii, and Feline herpesvirus 1 (FHV-1), further supporting the non-infectious hypotesis (2). A possible link between feline plasma cell pododermatitis and concurrent feline immunodeficient virus (FIV) infection was suggested in one study, but the role of the virus remains controversial. Plasma cell pododermatitis has been also treated with wide surgical excision of the affected footpads, suggesting that other factors are probably involved (4).

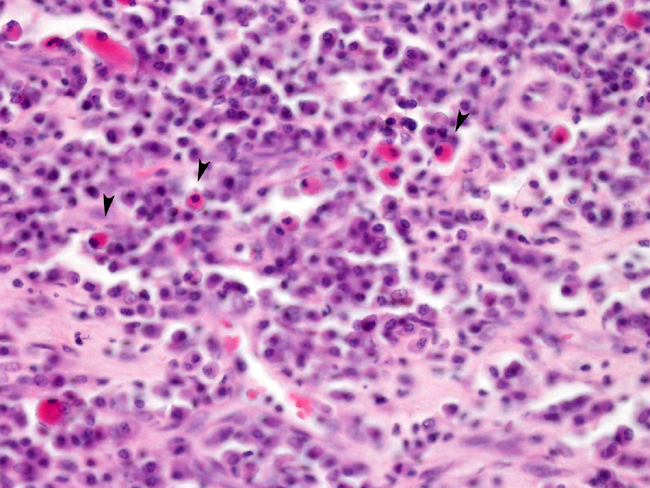

Histologically, lesions are characterized by large numbers of plasma cells, occasionally in a predominantly perivascular pattern. The dermis and often the underlying adipose tissue of the pawpads are diffusely infiltrated with plasma cells. Russell body-containing plasma cells (Mott cells) are often conspicuous. Binucleated plasma cells and mitoses have also been described (4). The epidermis is acanthotic with variable erosion, ulceration, and exudation. Neutrophilic infiltration is variable, but neutrophils can be up to 50% of the infiltrate and their presence is not dependent upon ulceration. Eosinophils are rare. Edema of the dermis, deep perivascular tissue, or interlobular septa of the fat pad may be seen. Blood vessels are often prominently dilated and congested, and hemorrhage may be present (6).

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Mott cells are plasma cells that contain large eosinophilic, amorphous globules (Russell bodies) within their cytoplasm. These Russell bodies are composed of immunoglobulin (γ globulin).(8) Characteristic features of plasma cells on a transmission electron micrograph include an eccentric nucleus, alternating areas of electron dense heterochromatin, and electron lucent euchromatin forming a cart-wheel pattern, a prominent Golgi apparatus (the perinuclear hof seen in light microscopic section), abundant rough endoplasmic reticulum (cytoplasmic basophilia in light microscopic section), and few mitochondria.(9)

Conference participants discussed the concurrent findings of plasmacytic stomatitis, immune-mediated glomerulonephritis, and renal amyloidosis that are occasionally seen in animals with plasmacytic pododermatitis. AA amyloid (reactive systemic amyloidosis) is the most common form found in animals, where AL amyloid (Immunoglobulin-derived amyloidosis) is the most common form in humans.(3) In cats, amyloid in the kidney is most commonly deposited in the interstitial spaces of the medulla with relative sparing of the glomerulus. In most other animals, amyloid is primarily deposited in the glomerulus.(3) However, in familial amyloidosis, the amyloid is primarily deposited in the renal medullary interstitium in the Shar Pei dog and the glomerulus in the Abyssinian cat, while it is primarily deposited in the liver in Siamese cats.(10)

References:

2. Bettenay SV, Lappin MR, Mueller RS: An immunohistochemical and polymerase chain reaction evaluation of feline plasmacytic pododermatitis. Vet Pathol 44:80-83, 2007

3. Charles JA: Pancreas. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 4th ed., vol. 2, pp. 463465. Elsevier Limited, St. Louis, MO, 2007

4. Dias Pereira P, Faustino AM: Feline plasma cell pododermatitis: a study of 8 cases. Vet Dermatol 14:333-337, 2003

5. Ginn PE, Mansell JEKL, Rakich PM: Skin and appendages. In: Pathology of Domestic Animals, eds. Jubb KVF, Kennedy PC, Palmer N, 5th ed., vol. 1, pp. 661-662. Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 2007

6. Gross TL, Ihrke PJ, Walder EJ, Affolter VK: Plasma cell pododermatitis. In: Skin disease of the dog and the cat, 2nd ed., pp. 363-364, Blackwell Science, Ames, IA, 2005

7. Gruffydd-Jones TJ, Orr CM, Lucke VM: Foot pad swelling and ulceration in cats: a report of five cases. J Small Anim Pract 21:381-389, 1980

8. Myers RK, McGavin MD: Cellular and tissue responses to injury. In: Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease, eds. McGavin MD, Zachary JF, 4th ed., p. 43. Elsevier, St. Louis, MO, 2007

9. Porter KR, Bonneville MA: Fine Structure of Cells and Tissues, 3rd ed., pp. 2-5, Lea & Febiger, Philadelphia, PA, 1968

10. Snyder PW: Diseases of immunity. In: Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease, eds. McGavin MD, Zachary JF, 4th ed., pp. 247-249. Elsevier, St. Louis, MO, 2007

11. Taylor JE, Scmeitzel LP: Plasma cell pododermatitis with chronic footpad haemorrhage in two cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 197:375-377, 1990