CASE II: MB19-317 (JPC 4166552)

Signalment:

An 8-year-old, 28.5 kg, castrated male, boxer dog (Canis lupus familiaris)

History:

The intact male dog was presented for bilateral perineal hernia and right unilateral cryptorchidism. The left testicle was descended in the scrotum. Abdominal ultrasound noted prostatomegaly, sublumbar lymphadenomegaly, minimal abdominal effusion, and an intraabdominal mass suspected to be an enlarged retained right testicle (cryptorchid). Surgical intervention included bilateral perineal hernia repair, left orchiectomy with scrotal ablation, and right cryptorchidectomy. Noted during the celiotomy, the peritoneum was diffusely thickened and multinodular with increased peritoneal effusion. The left testicle with scrotum, the intraabdominal enlarged right testicle, and portions of the multinodular peritoneum were submitted for pathological examination.

Gross Pathology:

Received 3 labeled jars with tissue fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin. Jar 1, "body wall", has one tissue (peritoneum) that is 1.4 x 0.9 x 0.5 cm, is tan and irregularly rectangular. Jar 2, "intraabdominal wall testicle", has one tissue that is 5.5 x 4 x 3.5 cm with features that are consistent with testicle (right). The epididymis and an area of the tunica albuginea are roughened, tan, and granular. The portion of the tissue that corresponds to testicle measures 4.5 x 3.5 x 3.5 cm. On cross-section, the testicle is firm, tan, and multilobular traversed by haphazard and arborizing subtle tan streaks. Jar 3, "scrotum descend testicle", has one tissue composed of testicle (left) and skin (scrotum) that measures 4.5 x 3 x 1 cm. The elliptical portion of skin has a 2 cm long and 0.5 cm diameter tan fibrous stalk that attaches to the teste. The testicle measures 3.5 x 2.5 x 2 cm and on section the tunica albuginea is diffusely thickened and firm up to 0.5 cm and this tissue melds with the previously described stalk.

Laboratory Results:

No laboratory findings reported.

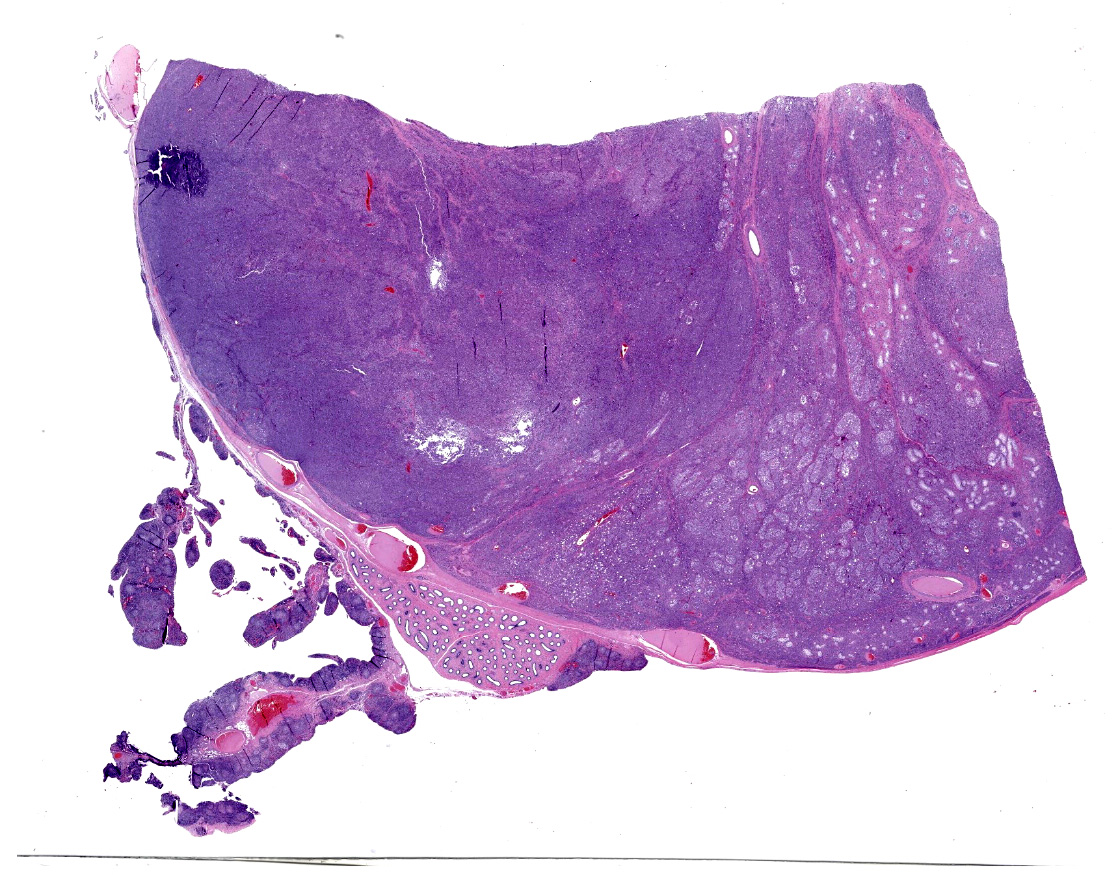

Microscopic Description:

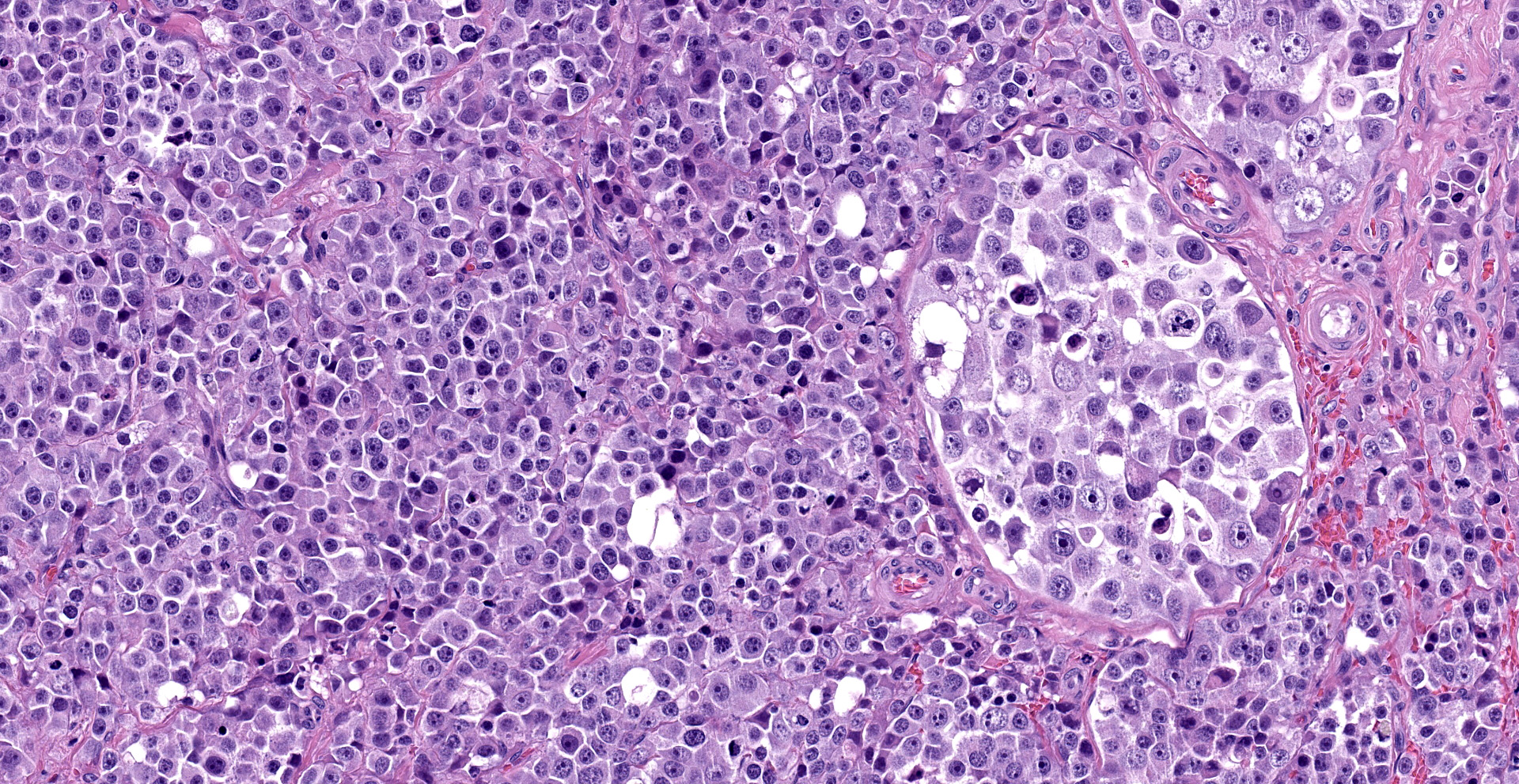

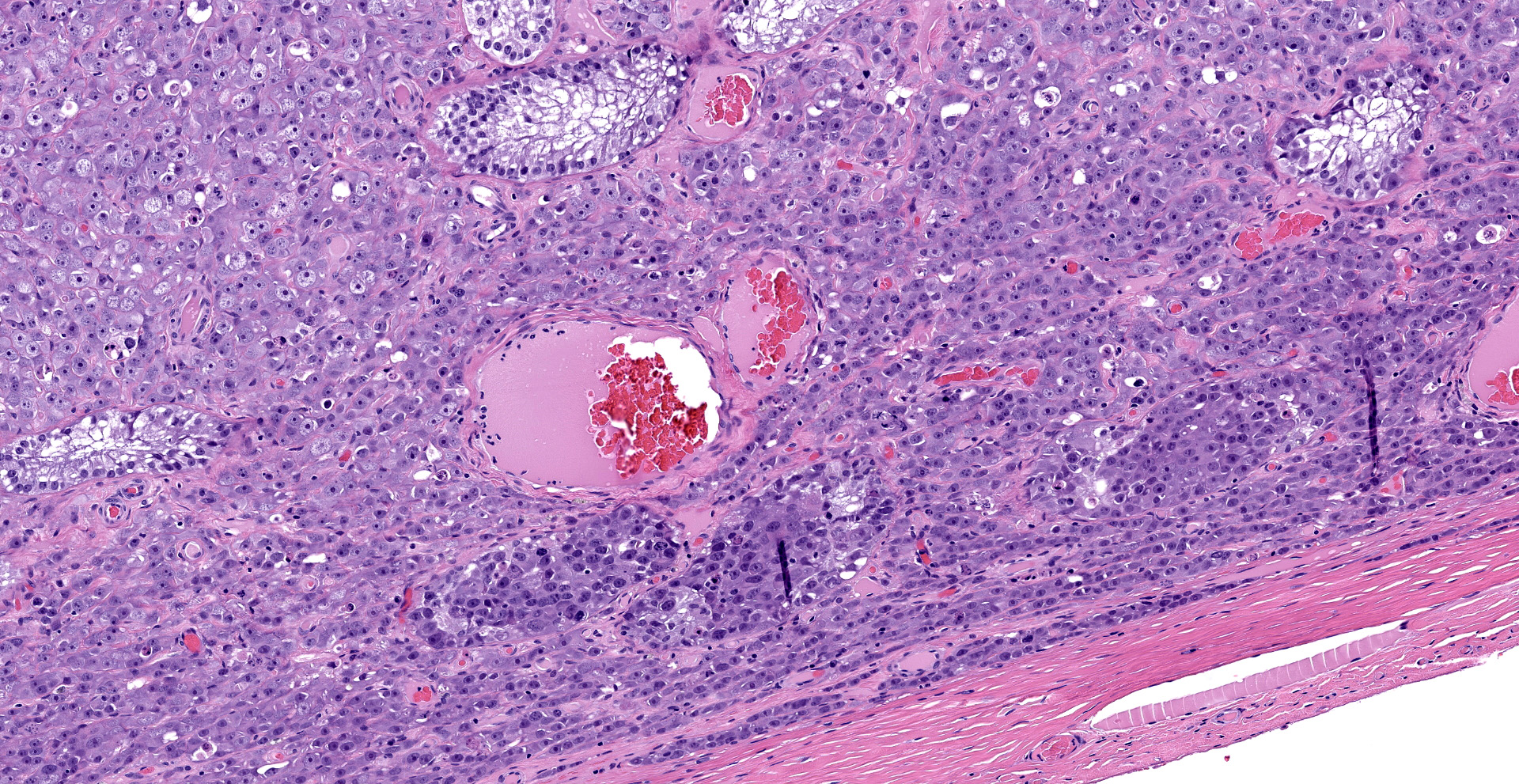

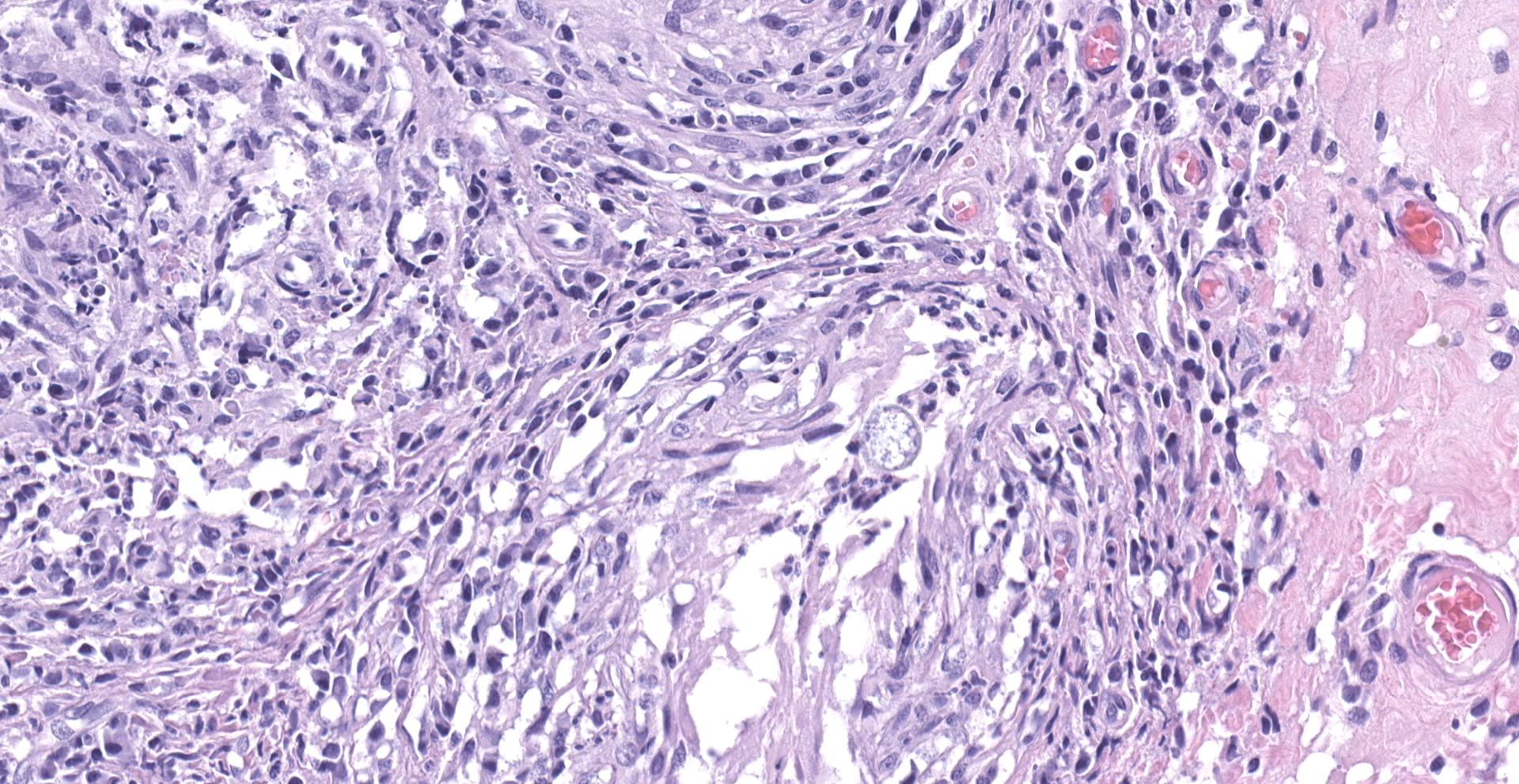

"Intraabdominal wall testicle", enlarged cryptorchid right testicle: Nearly diffusely replacing tissue architecture, associated with few atrophied remnant seminiferous tubules that contain only Sertoli cells, and extending into the tunica albuginea there is a moderately well-demarcated, unencapsulated, infiltrative, and highly cellular testicular germ cell tumor that is arranged in intratubular to diffuse sheets of densely packed round cells. Arrangements are supported by marked haphazard arborizing fibrous connective tissue. Cells are round to polygonal, have moderate eosinophilic cytoplasm, and large round to oblong vesiculated nuclei with prominent up to 4 central magenta nucleoli and occasional nuclear cytoplasmic inclusions. There is frequent individual cell apoptosis/necrosis with suspected phagocytosis (starry-sky pattern). Mitoses are 13 per 2.4 mm2 (equivalent to 10 FN22/40X fields) and some are atypical. Multifocally in the stroma are lymphocyte and plasma cell aggregates. There is moderate to marked anisocytosis and anisokaryosis. There is karyomegaly and occasional multinucleation. Multifocal vessels contain luminal tumor cells (unclear if this represents true vascular invasion or transposed cells that occurred during trimming). Tumor cells extend into the tunica albuginea (invasion). Lining the serosa of the epididymis, the ductus deferens, the tunica albuginea, and the vascular adventitia are multifocal to coalescing pyogranulomas. Centrally, admixed with neutrophils and cell debris, there are round, < 30 um diameter organisms that have a refractile capsule that surround vacuolated basophilic wispy material or that contain packed 3 um round basophilic structures (developing spherules, variably with endospores) (Coccidioides spp.). This is followed by epithelioid

macrophages, few multinucleated giant cells, lymphocytes, plasma cells, fibrosis, neovascularization, and reactive hypertrophied mesothelium. At one aspect of the tissue, architecture is smudged and coagulated with nuclear streaming (cautery artifact).

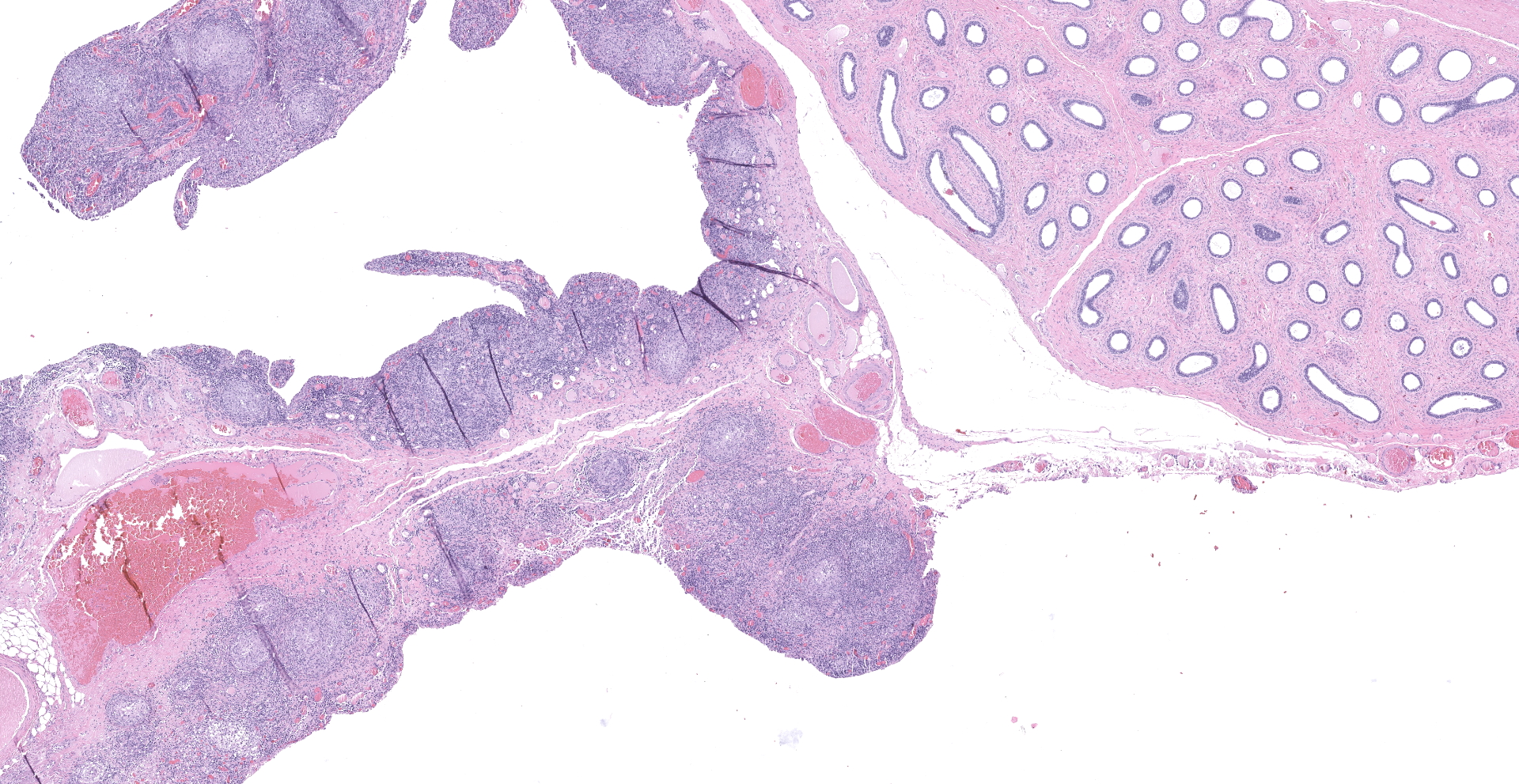

Body wall (peritoneum) (not submitted): Thickening the peritoneum, admixed with fibrosis, reactive hypertrophied mesothelium, and above regions of skeletal muscle bundles there are pyogranulomas containing fungal spherules with occasional endosporulation (Coccidioides spp.), as previously described.

Descended testicle (left) with scrotum (not submitted): Multifocally thickening and infiltrating the tunica albuginea and tunica vaginalis, among portions of the epididymis and supported by fibrosis, there are pyogranulomas containing fungal spherules with occasional endosporulation (Coccidioides spp.), as previously described. The testicular parenchyma is variably compressed by the peripheral enflamed fibroplasia, and seminiferous tubules have reduced cellularity without spermatids (atrophy) with mild interstitial fibrosis.

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnosis:

1. Testicle, intraabdominal cryptorchid, right: Seminoma, intratubular and diffuse-types, with invasion of the tunica albuginea.

2. Testicle, intraabdominal cryptorchid, right: Periorchitis, pyogranulomatous, lymphoplasmacytic, marked, chronic, with intralesional fungal spherules (Coccidioides spp.).

3. Abdomen and descended testicle (not submitted), left: Peritonitis and periorchitis, pyogranulomatous, lymphoplasmacytic, marked, chronic, with intralesional fungal spherules (Coccidioides spp.).

Contributor's Comment:

The dog was diagnosed with two simultaneous but unrelated disease processes, one neoplastic and one infectious. The cryptorchid right testicle was enlarged by a seminoma with features of both, intratubular and diffuse type patterns.2 Definitive vascular invasion was lacking, but neoplastic cells did regionally invade the tunica albuginea. The biopsy of peritoneal tissue, the intraabdominal testicle's capsule, and the descended testicle's capsule and peripheral space (tunica vaginalis) were diffusely thickened by chronic inflammation dominated by pyogranulomas containing fungal spherules with variable endosporulation, consistent with Coccidioides spp. The fungal periorchitis of the descended left testicle was likely the extension of the peritoneal infection to the vaginal process, since the latter, demarcated by the parietal and visceral vaginal tunics, is a continuation of the abdominal cavity. A regional intrascrotal fungal inoculation of the left testis is another possibility, though less likely given the dog's marked fungal peritonitis.

Common testicular tumors of the dog are Sertoli cell tumor, interstitial or Leydig cell tumor, and seminoma.2,8 Typically, these testicular tumors are benign; however, their malignancy is difficult to determine based solely on cell morphology. Therefore, a definitive designation of malignancy requires recognizing metastasis in the spermatic cord, regional lymphatics, sentinel lymph nodes, or in distant sites.2 Seminomas are the most common germ cell tumor of older dogs, and these tumors are typically hormonally inactive and prevalent in cryptorchid testes.2 Grossly, seminomas are lobulated, white to gray-white, soft, bulge on section, and may have hemorrhage.2 Microscopic features are characteristic, and include the growth of densely packed sheets of polygonal round cells that may arrange in tubules or diffuse pattern or a combination.2,8 As in humans, the expression of c-KIT and PLAP in dog seminomas may allow further differentiation between spermatocytic or classical

seminoma, which may have prognostic implications.8

Coccidioidomycosis is a localized to systemic infection caused by the dimorphic fungi Coccidioides immitis and Coccidioides posadasii.5 These fungi are saprobic and endemic in dry climates of the southwestern United States (US), Mexico, Central America, and South America.9 Current climate change scenarios predict that by 2100 Coccidioides spp. endemicity in the US will expand northward into drying western states accompanied by a 50% increase in human infections.4 In addition to humans, these fungi infect a wide range of mammals with varying susceptibility.1,5,11 The primary route of infection is through the inhalation of environmental arthrospores or less likely, following direct cutaneous inoculation.5 Once inhaled, the infection may be limited to the lung (pneumonia) and draining lymph nodes (lymphadenitis) or the infection may become disseminated, spreading hematogenously or lymphogenously to distant sites.5 Lameness resulting from fungal granulomatous osteomyelitis is a common indication of disseminated disease.5

Young, large breed dogs spending time outdoors in endemic areas, especially as working or sporting dogs or roaming deserts, are at increased risk for coccidioidomycosis.5 Infected dogs display a variety of clinical signs and disease severity, which renders definitive diagnosis difficult.5,7,9 Because of the inhalation route of infection, clinical signs attributable to fungal pneumonia are common; however, dogs with disseminated disease may not always have history of respiratory morbidity.5 Moreover, the highly diverse patterns of systemic dissemination preclude a case definition and result in atypical infections, such that in endemic areas coccidioidomycosis is often a differential diagnosis in ill dogs. Coccidioides spp. can disseminate anywhere in the body, including central nervous system, bone, pericardium, eye, reproductive tissue, parenchymal organs, endocrine tissue, gastrointestinal tract, and, as in this case, peritoneum.9 Where a clinical suspicion of coccidioidomycosis exists, serology for immunoglobin (Ig) G and IgM is an available screening tool in dogs, albeit imperfect.7 A retrospective study found that the sensitivity of a commercially available agar gel immunodiffusion assay (AGID) serologic test for canine coccidioidomycosis was 87% for IgG and 46% for IgM.7 The advent of an enhanced enzyme immunoassay to detect Coccidioides spp. antibodies shows promise to be more sensitive and specific than AGID.7 Multiple studies suggest that elevated IgM occurs with acute disease, while elevated IgG indicates chronic or disseminated disease or both.7

This dog's diagnosis of disseminated coccidioidomycosis was fortuitous. The primary complaint was perineal hernia and unilateral cryptorchidism with likely neoplasia. This dog did not present with morbidity concerning for Coccidioides spp. infection. However, all biopsies detected peritoneal coccidioidomycosis. Serum collected the day after the biopsies yielded positive Coccidioides spp. IgM (1:4) and IgG (1:32) titers. It is probable that this patient's coccidioidomycosis involved more than the peritoneal cavity, but additional diagnostics, including thoracic radiographs were not pursued. The patient's sublumbar lymphadenomegaly could represent fungal lymphadenitis or perhaps seminoma metastasis or may simply be immunologic lymphoid hyperplasia. Following the Coccidioides spp. diagnosis, the dog was prescribed fluconazole per os twice daily. Six months later, upon titer reevaluation, the patient continued to have positive Coccidioides spp. IgM (1:4) and IgG (1:8) titers. The decreasing IgG titer is likely a result of treatment.5 More than a year later, the patient is alive, though the extensiveness of its coccidioidomycosis and the possibility of seminoma metastasis was never fully investigated.

Contributing Institution:

Midwestern University, College of Veterinary Medicine

Diagnostic Pathology Center

5725 West Utopia road

Glendale, Arizona 85308

JPC Diagnoses:

1. Testis: Seminoma.

2. Testis: Hypoplasia and aspermato-genesis, diffuse, severe.

3. Testis, vaginal tunics and spermatic cord: Pyogranulomas, multiple, with endosporulating spherules, etiology consistent with Coccidioides sp.

JPC Comment:

The contributor provides an excellent review of both entities presented in this patient that presented for what was anticipated to be a "routine" cryptorchid castration.

Cox, Wallace, and Jessen first suggested a hereditary basis for cryptorchidism in dogs in 1978; however, Gubbels, Scholten, Janss, and Rothuizen provided convincing evidence in 2009 following the evaluation of data from 11,230 litters in 12 purebred dog breeds. Matings involving presumed carriers (parent of at least one previously identified cryptorchid) were associated with a 24.1% rate of cryptorchidism compared to 2.1% in the overall population.10

Cryptorchid dogs are at increased risk for testicular neoplasia (especially Sertoli cell tumors and seminomas) and spermatic cord torsion. In addition, cryptorchidism has been found to be associated with umbilical and inguinal hernias, hip dysplasia, patellar luxation, penile and preputial defects, and occurs in up to 50% of dogs with persistent Müllerian duct syndrome (PMDS).10, 12 PMDS is rare form of male pseudohermaphroditism characterized by the existence of a hypoplastic oviduct, uterus, and cranial vagina and is associated with an autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance most commonly observed in miniature schnauzers.12

Testicular neoplasia commonly occurs in dogs, with one study6 reporting 62 (27%) of 232 male dogs between 80 days and 15 years (mean 10.7 years) of age presented for necropsy to be affected. Many affected animals had more than one testicular tumor, with a total of 110 identified. Although seminiomas are commonly reported to be the most common testicular neoplasm, interstitial cell tumors were the most commonly reported testicular neoplasm in this study (50%), followed by seminomas (42%), and Sertoli cell tumors were the least common (8%). Of the 62 dogs with testicular tumors, 19 had more than one tumor type while two had all three.6

Testicular tumors typically have unique macroscopic and histologic features, with those of seminomas being previously described by the contributor. Macroscopically, interstitial cell tumors are typically yellow to brown, soft, nodular masses with hemorrhagic foci. Histologically, interstitial cell tumors are composed of round to polygonal cells with finely vacuolated eosinophilic cytoplasm, an eccentric round nucleus, and have rare mitotic figures. Sertoli cell tumors typically present as grey to white, firm, multinodular masses that are clearly demarcated from surrounding parenchyma. Histologically, Sertoli cell tumors may demonstrate diffuse, intratubular, or a combination of growth patterns and are characterized by elongated cells with faintly eosinophilic cytoplasm often arranged in palisades lining well-delineated tubular structures associated with abundant fibrous stroma and rare mitotic figures.6

Dr. Myrnie Gifford, an assistant health officer in Kern County, California was the first physician to identify Coccidioides spp. as the etiologic agent of "San Joaquin Valley Fever" in 1934. Shortly thereafter, between 1945 and 1951, Drs. Phyllis Edwards and Caroll Palmer conducted an extensive seroprevalence study using over 110,000 Navy recruits, student nurses, and college students, resulting in the first known map of the disease's distribution across The United States.3

As noted by the contributor, the environment plays a significant role in this pathogen's growth and life stages. Thought to proliferate during short-lived wet conditions in an otherwise arid environment, Coccidiodes subsequently autolyzes into infective arthroconidia when stressed by hot and dry conditions, which are then dispersed by wind. As a result, the climate of preceding seasons has been shown to play a significant role in the incidence of coccidiomycosis. For example, higher rates of human coccidiomycosis have been reported in the San Joaquin Valley of California during autumns following cooler and wetter springs.3

Between 7000 and 9000 protein coding genes exist in the Coccidioides genome, which as a whole is poorly understood. Less than 10 genes have been functionally characterized so far, many of which are related to virulence. Interestingly, ammonia production appears to play a role in virulence during spherule development and rupture. Deletion of urease gene (URE) resulted in partial reduction of ammonia and increased the survival of mice by 60%, whereas double deletion of urease and ureidoglycolatehydrolase (Ugh) genes resulted in even lower ammonia levels and increased the survival of mice to 90%.

Studies have shown the host's innate immune response to Coccidiodes spherules relies on TLR2, myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88) and Dectin-1. In addition, T cells have been shown to play a crucial role in the body's defense against Coccidiodies, as Th1 responses associated with IL-12 and IFN-γ and Th17 responses activated by IL-17 and IL-22 are both critical for protection against coccidiomycosis.3

During the conference the moderator emphasized the risk posed to laboratory personnel by Coccidiodes spp. Infected animals are not contagious; however, infective arthroconidia formed when the organism is cultured can be inhaled if proper safety protocols are not followed. Therefore, laboratory personnel should always be notified when samples from potential cases of coccidiomycosis are submitted for culture as a professional courtesy.

References:

1. Adaska JM. Peritoneal Coccidioidomycosis in a Mountain Lion in California. J Wildl Dis 1999;35(1):75-77

2. Foster RA. Male Genital System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO; 2016:465-510.

3. Gorris ME, Caballero Van Dyke MC, Carey A, Hamm PS, Mead HL, Uehling JK. A Review of Coccidioides Research, Outstanding Questions in the Field, and Contributions by Women Scientists [published online ahead of print, 2021 Aug 2]. Curr Clin Microbiol Rep. 2021;1-15.

4. Gorris ME, Treseder KK, Zender CS, Randerson JT. Expansion of coccidioidomycosis endemic regions in the United States in response to climate change. GeoHealth 2019:308-327.

5. Graupmann-Kuzma A, Valentine BA, Shubitz LF, et al. Coccidioidomycosis in Dogs and Cats: A Review. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2008;44(5):226?235.

6. Grieco V, Riccardi E, Greppi GF, Teruzzi F, Iermanò V, Finazzi M. Canine testicular tumours: a study on 232 dogs. J Comp Pathol. 2008;138(2-3):86-89.

7. Gunstra A, Steurer JA, Seibert RL, Dixon BC, Russell DS. Sensitivity of Serologic Testing for Dogs Diagnosed with Coccidioidomycosis on Histology: 52 Cases (2012?2013). J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2019;55(5):238?242.

8. Hoh?teter M, Artuković B, Severin K, et al. Canine testicular tumors: two types of seminomas can be differentiated by immunohistochemistry. BMC Vet Res 2014;10:169

9. Izquierdo A, Jaffey JA, Szabo S, et al. Coccidioides posadasii in a Dog With Cervical Dissemination Complicated by Esophageal Fistula. Front Vet Sci 2020;7:285.

10. Khan FA, Gartley CJ, Khanam A. Canine cryptorchidism: An update. Reprod Domest Anim. 2018;53(6):1263-1270.

11. Koistinen K, Mullaney L, Bell T, et al. Coccidioidomycosis in Nonhuman Primates: Pathologic and Clinical Findings. Vet Pathol. 2018;55(6): 905?915.

12. Park EJ, Lee SH, Jo YK, et al. Coincidence of Persistent Müllerian duct syndrome and testicular tumors in dogs. BMC Vet Res. 2017;13(1):156. Published 2017 Jun 2.