Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2017-2018

Conference 23

April 25th, 2018

CASE III: 16-41394 (JPC 4100931).

Signalment: 14-week-old, male, intact, mixed breed (Canis familiaris), canine.

History: This animal had an approximately 4-week-long history of intermittent difficulty or inability to walk and/or stand, and vocalization due to pain upon light palpation. Clinical examination revealed positive deep pain on all four limbs and radiographs were unremarkable. Due to the poor quality of life, the animal was humanely euthanized.

Gross Pathology: The animal was in poor nutritional condition, and the costochondral joints from the seventh to thirteenth ribs were moderately enlarged and prominent. Upon longitudinal sectioning of long bones (femur, radius and ulna, tibia and fibula), no evident abnormalities were observed.

Laboratory Results (clinical pathology, microbiology, PCR, ELISA, etc.): None provided.

Microscopic Description:

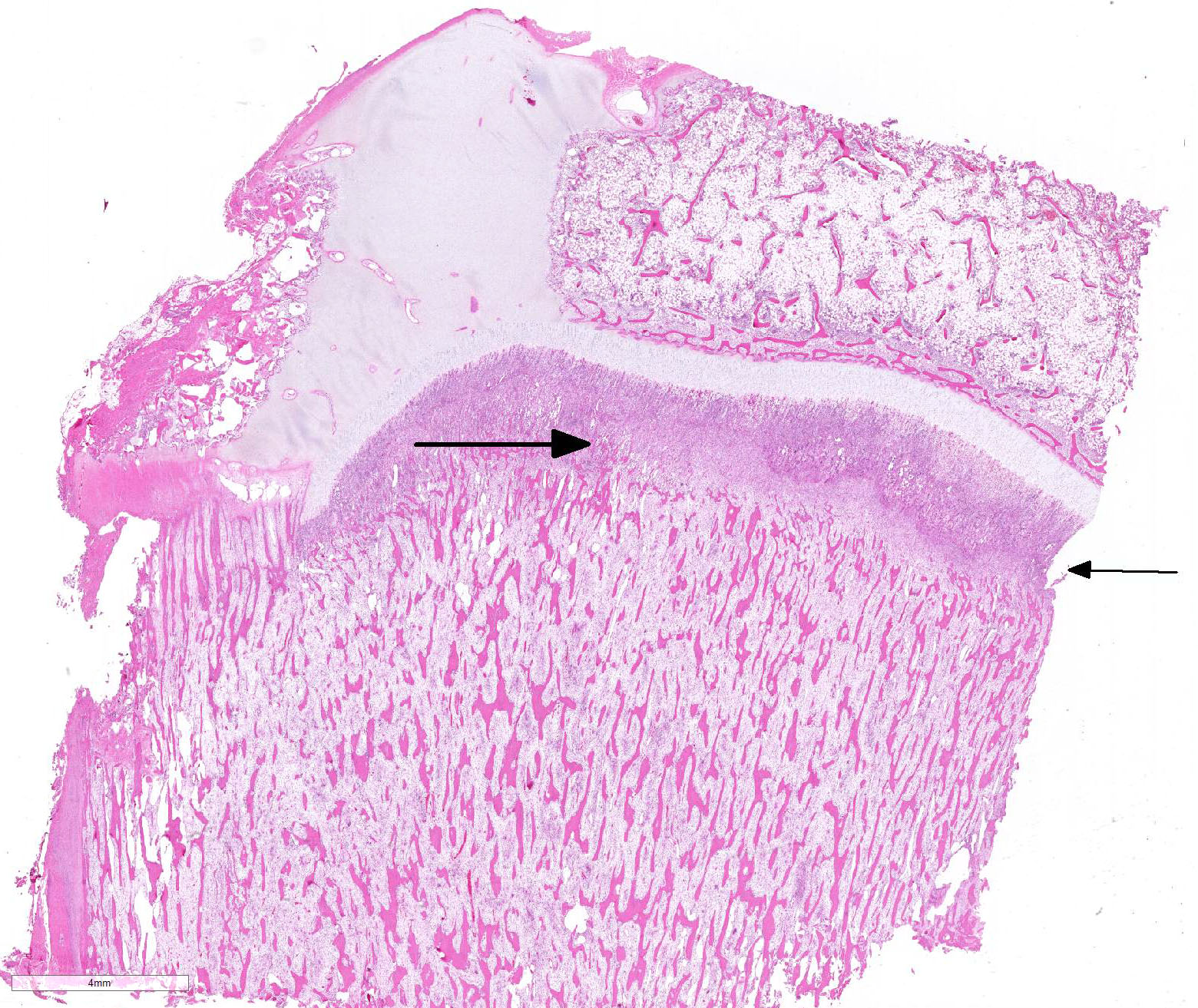

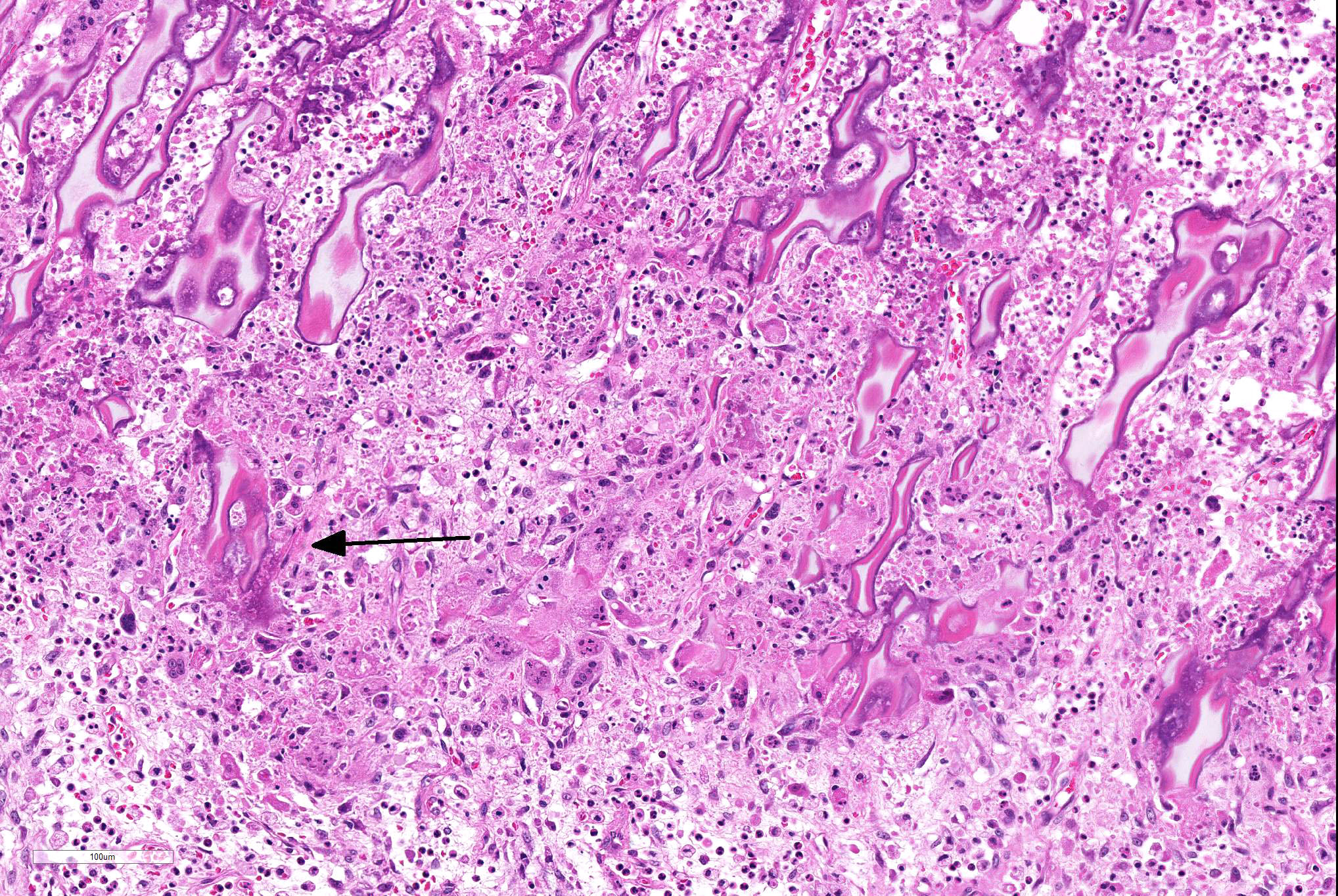

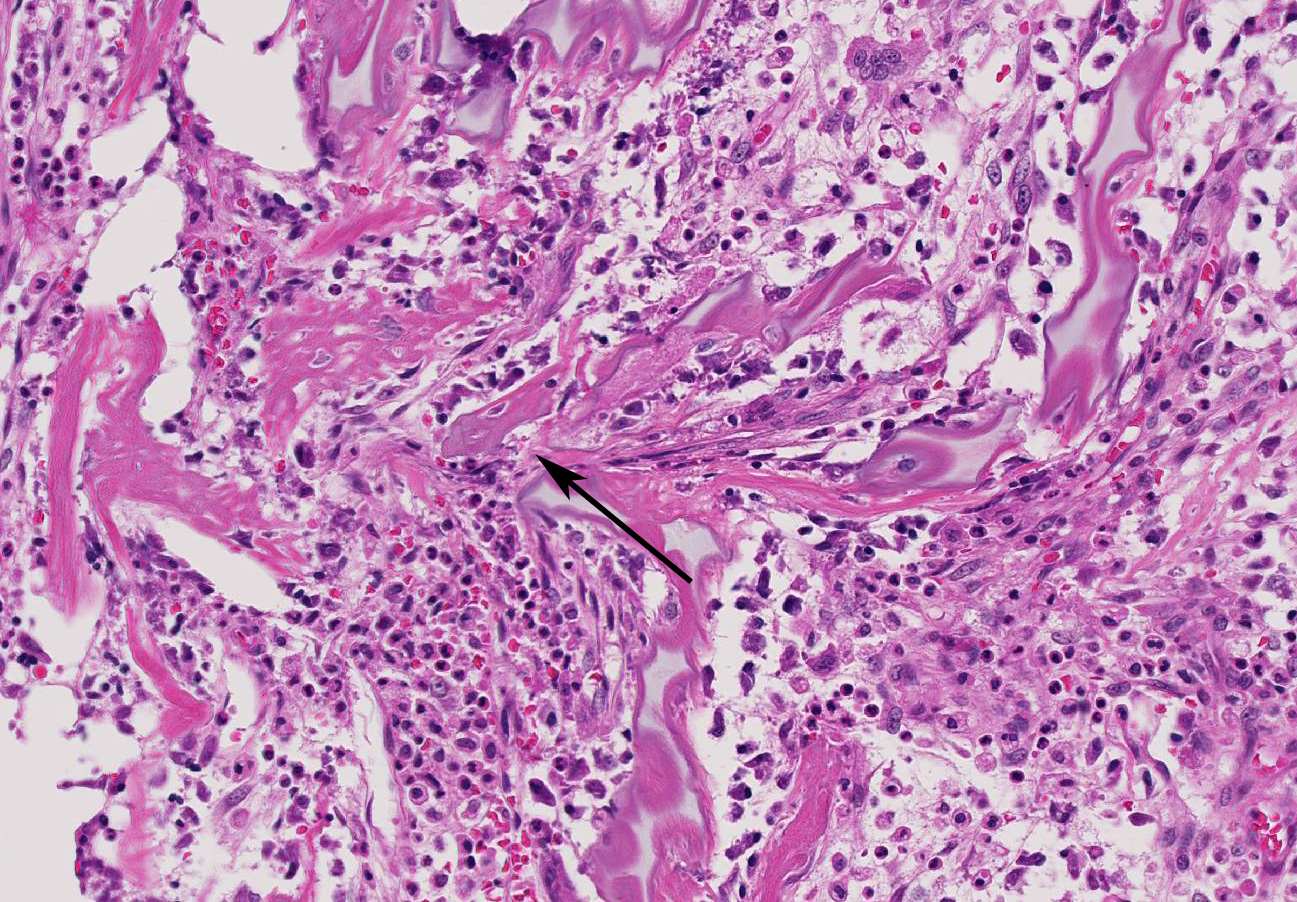

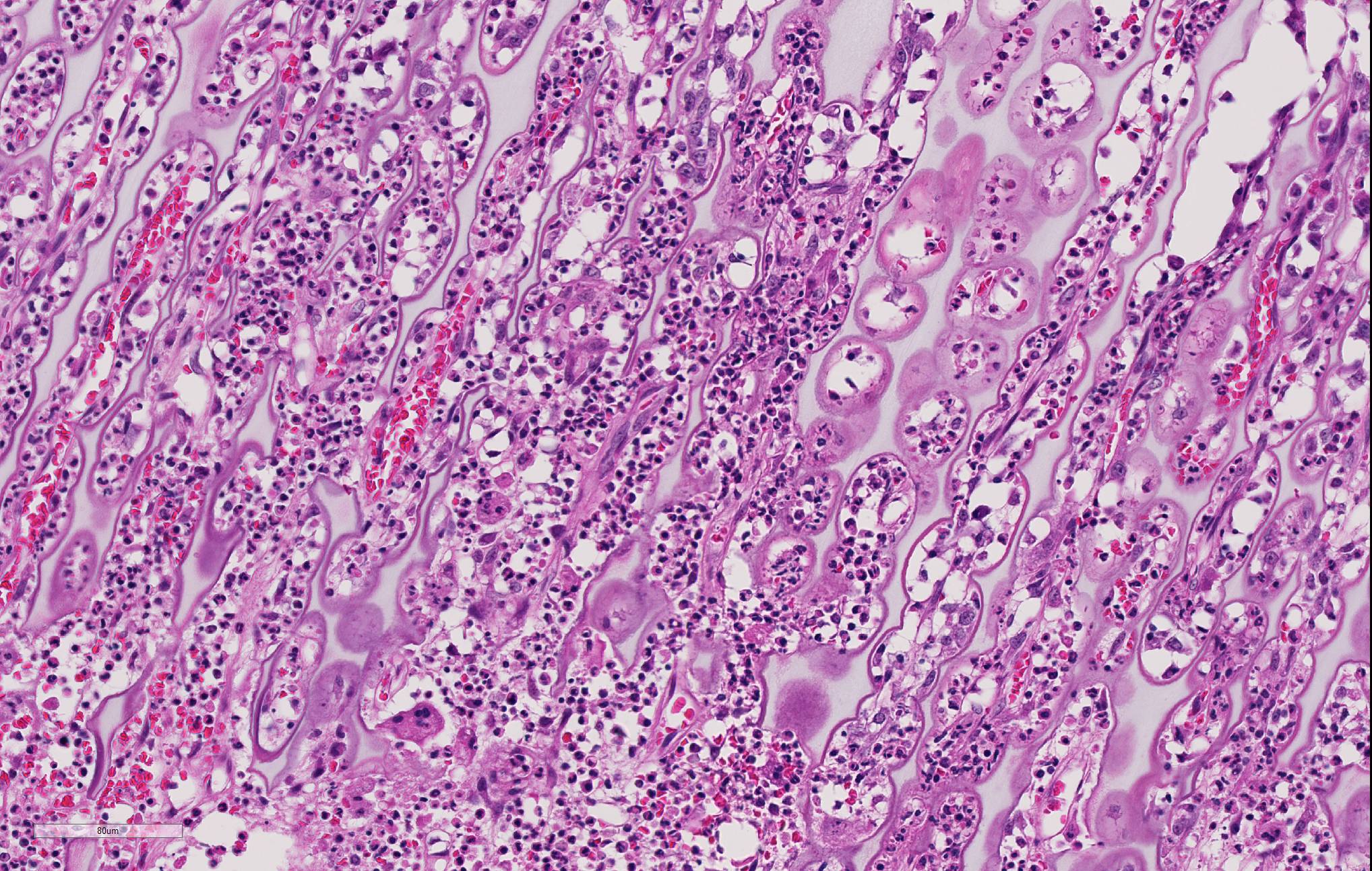

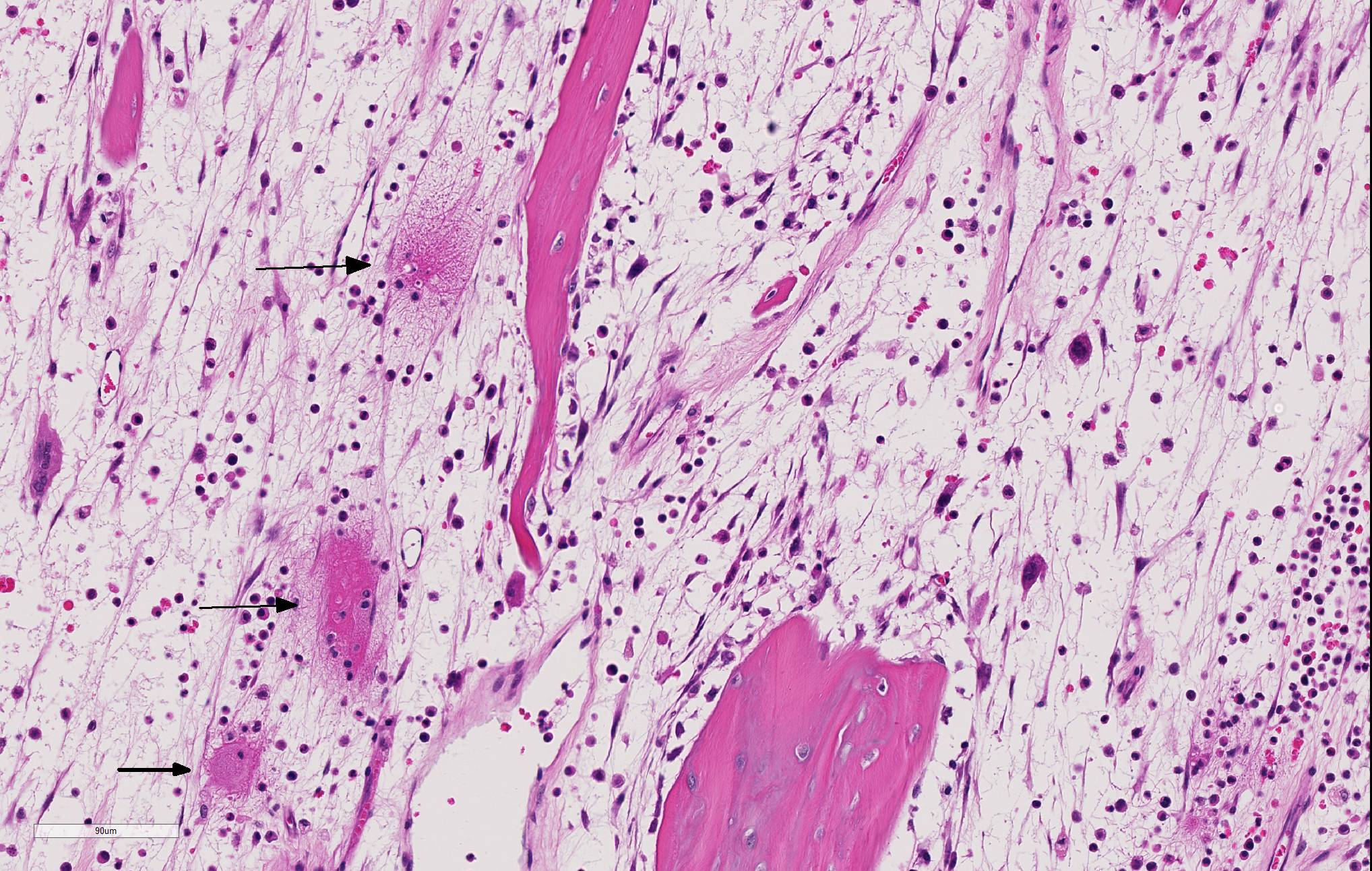

Long bone (tibia): Diffusely, the metaphysis is severely affected by inflammation accompanied by degeneration and necrosis. The primary spongiosa (ossification zone) is diffusely distorted and infiltrated by a thick band of numerous viable and degenerate neutrophils and fewer macrophages, among abundant pyknotic and karyorrhectic cellular debris and eosinophilic, loose, fibrillar material (fibrin). Inflammatory cells frequently replace the primary spongiosa and expand intertrabecular spaces, separating fragmented remnants of thinned and tortuous trabeculae, composed of amphophilic to hyperbasophilic, finely stippled to amorphous material (mineralized cartilage spicules). There is marked paucity to absence of osteoblasts lining the fragmented and sparse trabeculae. There are frequent osteoclasts scattered among the inflammatory infiltrate, abutting scalloped metaphyseal spicules. The inflammatory cells loosely extend into the underlying secondary spongiosa and, in a lesser extent, into the proximal and mid-diaphyseal medullary cavity. Frequent small caliber and thin walled blood vessels within the medullary cavity present hyaline profile due to bright eosinophilic, fibrillar material concentrically replacing the vascular wall (vascular fibrinoid necrosis).

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Metaphysis (tibia): Diffuse, severe, subacute, necrosuppurative osteomyelitis (metaphyseal osteopathy).

Contributor’s Comment: Considering the signalment, clinical history and similar histopathology affecting the costochondral joints, femur and tibia in a bilateral and symmetrical pattern, a diagnosis of metaphyseal osteopathy was concluded in this case.

Metaphyseal osteopathy, also known as hypertrophic osteodystrophy (HOD), is a developmental bone disease involving necrosis and suppurative inflammation affecting the metaphyseal region of long bones of rapidly growing young dogs.1,2 The disease has been reported in over 40 breeds, including mixed breed dogs. However, breed predisposition is commonly reported in Great Danes, Boxers, German Shepherds, Irish Setters, and Weimaraners.1,4 The latter is reported as the only breed where entire litters and closely related animals have been affected by the disease, strongly supporting a heritable component.4

The etiopathogenesis of metaphyseal osteopathy is not fully understood, and proposed mechanisms involving nutritional, infectious or vaccine-related reactions lack supporting scientific evidence.1 A recent study demonstrated overall overexpression of pro-inflammatory cytokines regulating innate immunity, such as Il-1b, IL-18, GM-CSF, CXCL10, TNF and IL-10, in affected dogs of two different breeds (Irish Setter and Weimaraner) supporting the hypothesis of an autoinflammatory disease.3

The condition can range from self-limiting with management with corticosteroid therapy to multisystemic involvement, potentially reaching overall debilitation and eventual death or euthanasia2, as ultimately happened in this case.

JPC Diagnosis: Long bone, metaphysis: Osteomyelitis, metaphyseal, necrotizing and neutrophilic, multifocal, moderate to severe with osteolysis and microfractures of the primary spongiosa, mixed breed (Canis familiaris), canine.

Conference Comment: Metaphyseal osteopathy is a condition with an unknown etiology that affects young, growing, large breed dogs (breed predispositions listed above) with relapsing lameness, joint swelling, and pain of the distal radius and ulna most commonly. Radiographically, these areas correspond to the metaphysis parallel to the physis and have alternating linear, parallel radiodense and radiolucent zones. Grossly, lesions are bilaterally symmetrical and characterized by a pale band in the primary spongiosa adjacent to the physis that can develop into small fractures within the boney spicules of the spongiosa. With chronicity, the periosteum thicken to support the dysfunctional ossification within the spongiosa and appears as bulbous dilations. The microscopic appearance is diagnostic for this condition with persistence of the mineralized cartilage lattice of the primary spongiosa, marked neutrophilic inflammation surrounding trabeculae, necrosis and loss of osteoblasts, and sometimes increased osteoclasts. Secondarily, as noted grossly, trabeculae frequently fracture and the periosteal bone is markedly thickened. The suppurative inflammation frequently extends into the marrow cavity of the metaphysis resulting in necrosis of marrow contents and fibrin thrombi.1

The main differentials for metaphyseal osteopathy include: bacterial osteomyelitis/septic metaphysitis/polyarthritis, hypovitaminosis C, and panosteitis.

All bacterial causes would have a different radiographic appearance and colonies of bacteria microscopically. Hypovitaminosis C, or scurvy, also exhibits decreased osteoid deposition on the cartilaginous trabeculae (“scorbutic lattice”) of the primary spongiosa but lacks inflammation and necrosis. Ascorbic acid (vitamin C) is required for hydroxylation of proline and lysine during fibrillary collagen cross-linking. Cartilage that is not properly cross-linked is inherently weak leading to decreased osteoid, increased fragility of blood vessels (hemorrhages), and microfractures in bone.1

Finally, panosteitis does not occur within the metaphysis and often appears as cotton-like densities within the medullary space of long bones radiographically. Clinically, panosteitis affects similar ages and breeds as metaphyseal osteopathy, but manifests as “shifting leg lameness” which often resolves on its own as the animal grows. The radiodensities seen radiographically correspond to increasing amounts of fibrovascular tissue with are soon replaced by woven bone within the medullary cavity. There are several subsequent episodes of bone resorption and formation leading to characteristic resting and reversal lines microscopically. Additionally, there is rarely any inflammation present, despite the name “panosteitis”.1

Contributing Institution:

http://vetmed.illinois.edu/vet-resources/veterinary-diagnostic-laboratory/

References:

- Craig LE, Dittmer KE, Thompson, KG. Bones and joints. In: Zachary JF, McGavin MD, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby; 2016:83-84, 105-108.

- Greenwell CM, Brain PH, Dunn AL. Metaphyseal osteopathy in three Australian Kelpie siblings. Aust Vet J. 2014; 92(4):115-118.

- Safra N, Hitchens PL, Maverakis E, et al. Serum levels of innate immunity cytokines are elevated in dogs with metaphyseal osteopathy (hypertrophic osteodytrophy) during active disease and remission. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2016; 179:32-35.

- Safra N, Johnson EG, Lit L, et al. Clinical manifestations, response to treatment, and clinical outcome for Weimaraners with hypertrophic osteodystrophy: 53 cases (2009–2011). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2013; 242(9):1260-1266.