CASE 3: X-27229-14 (4066657-00)

Signalment:

Approximately 1 year-old, male, pastel, farmed mink, Neovison vison (formerly Mustela vison)

History:

A new line of pastel mink was purchased in the spring of 2014. One of the purchased juvenile mink subsequently developed irregular, coalescing, areas of alopecia and scaling over the dorsal trunk. That animal was culled. Later that fall, 4 more animals (out of 900) developed similar skin lesions. One of these mink was euthanized (using carbon monoxide inhalation) and sent for necropsy. This condition does not appear highly contagious as other mink in contact with affected ones did not develop lesions and the incidence of lesions was low. The farm of origin has rarely seen similar cases. The current ranch is reportedly free of Aleutian disease.

Gross Pathology:

A young, adult, male, pastel (light tan colored) mink was examined. The carcass had been frozen and thawed prior to examination. Along the dorsal trunk, extending from the shoulder to the lumbar area were irregular, coalescing, serpiginous or track-like, partially alopecic areas where the exposed skin was scaly and scabby. The remaining carcass was grossly unremarkable.

Laboratory results:

Bacterial culture of the affected skin yielded a moderate growth of normal flora and a heavy growth of fungi. The fungal isolates were subsequently cultured on both Sabouraud dextrose and potato-dextrose agar which produced powdery, white to cream-colored spores and hyaline hyphae with a distinct yellow pigmentation. Microscopic examination of these fungi identified macroconidia composed of 3-4 cells that were club-shaped with smooth walls. Spherical to pyriform or oblong, microconidia that formed dense grape-like clusters long the sides of mycelia were also noted. These findings were compatible with Trichophyton sp. Genomic DNA was extracted from the cultured isolates for gene amplification by PCR and sequencing that identified this organism as Trichophyton equinum (publication in process).

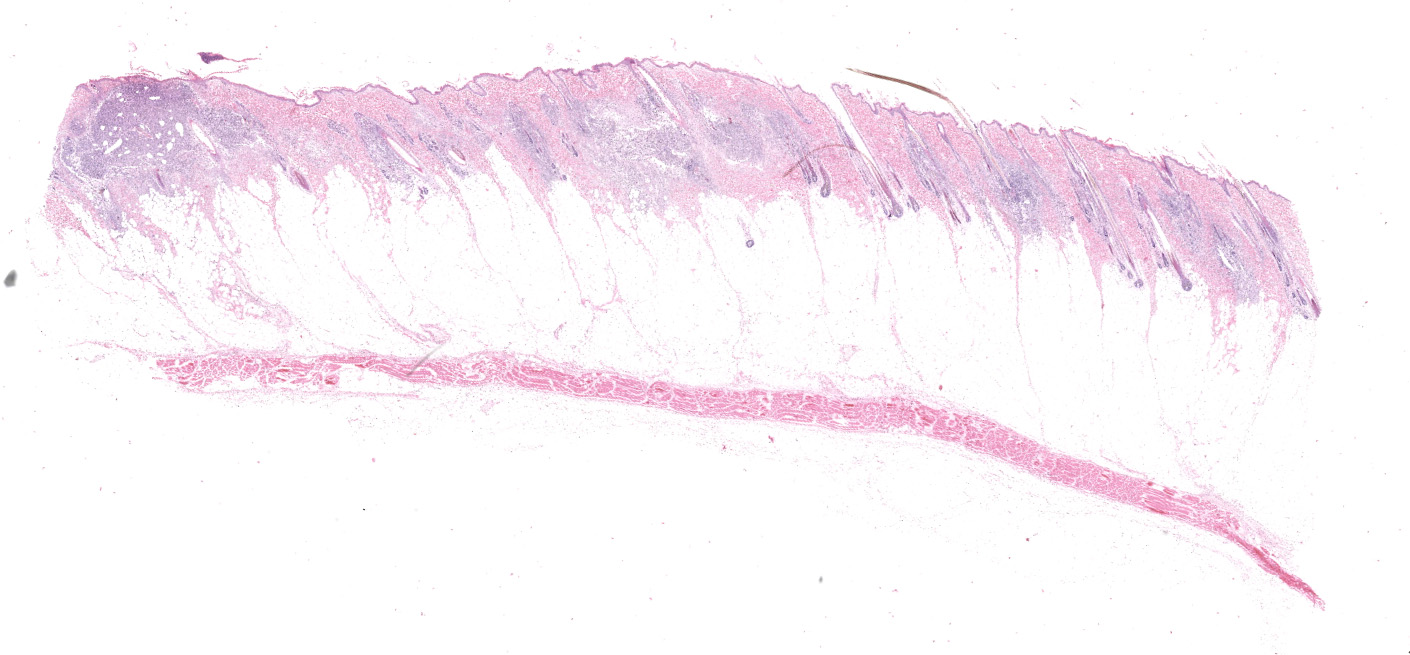

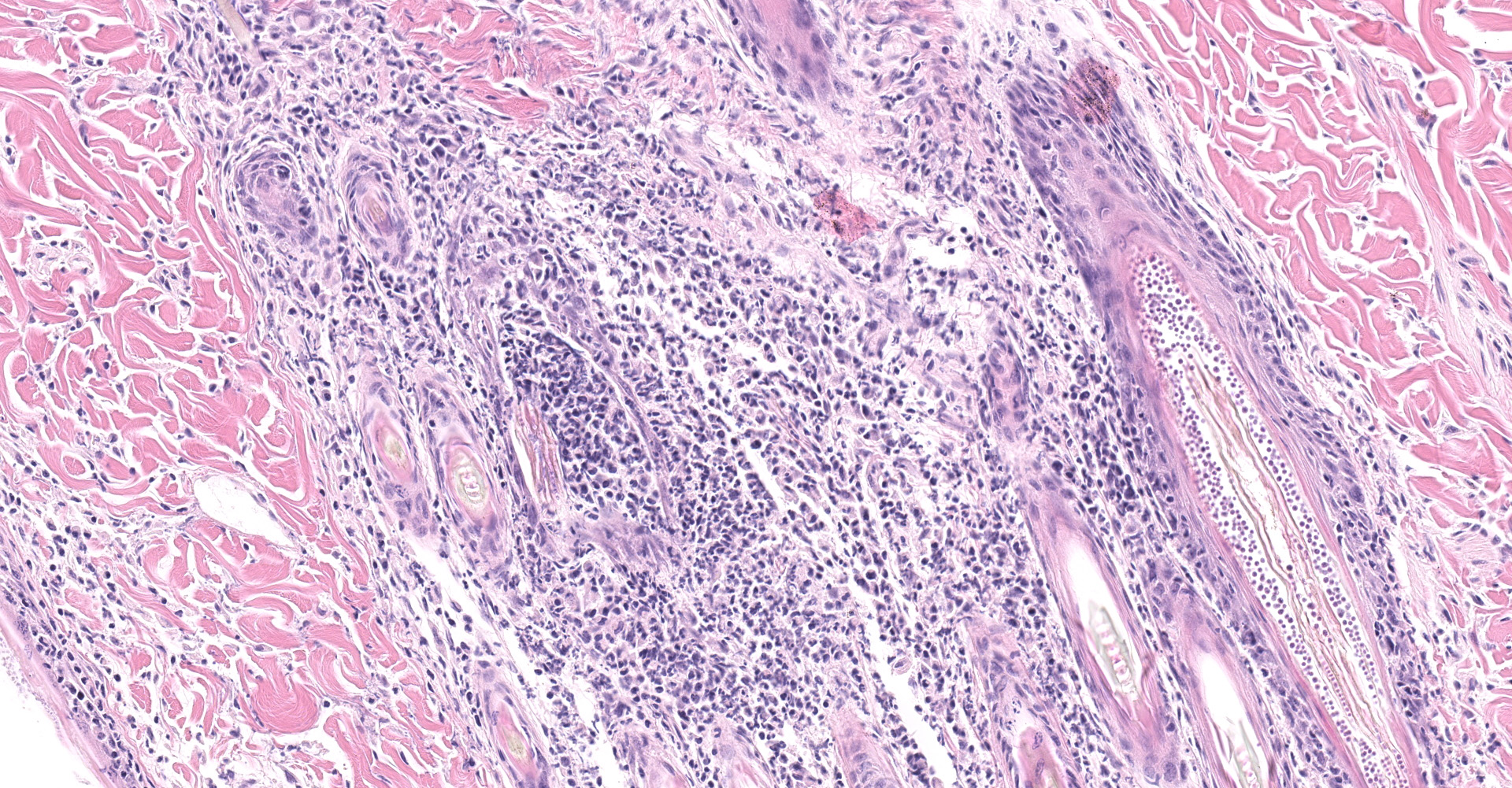

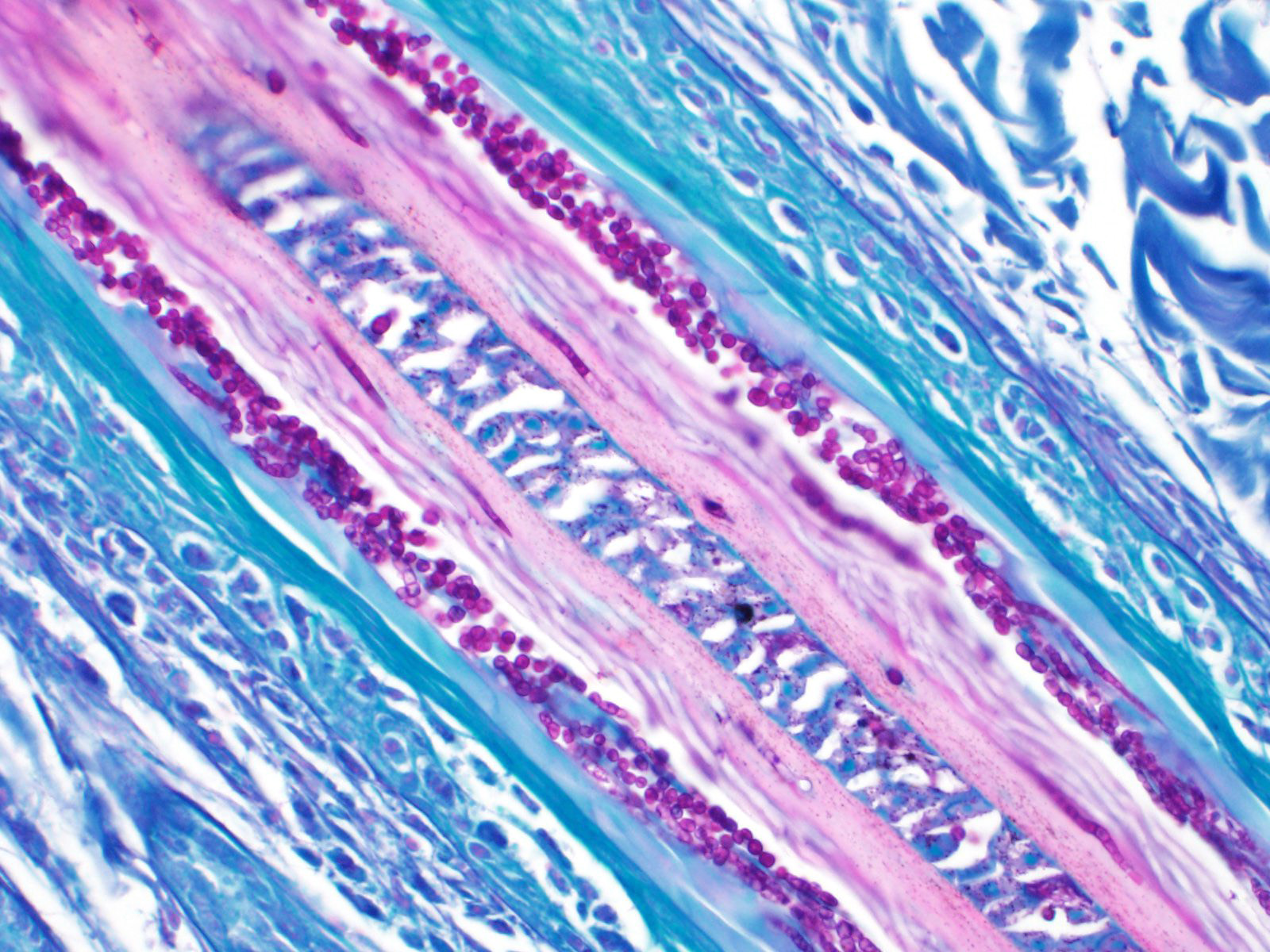

Microscopic description:

The epidermis was mildly hyperplastic and covered by increased amounts of dense, ortho- and parakeratotic keratin which contained occasional small intracorneal aggregates of degenerate neutrophils. The upper portions of the walls of hair follicles were similarly, mildly thickened. In scattered follicles, myriads of densely packed, round, basophilic, 1-2 micron in diameter, arthrospores encircled hair shafts (ectrothrix arthrospores). Fewer, similar endothrix arthrospores and pale staining endothrix hyphae were present within affected hair shafts. These follicles were surrounded by mild infiltrates of lymphocytes, plasma cells, few macrophages and rare neutrophils. Several adjacent hair follicles had ruptured and were replaced by dense, nodular aggregates of macrophages admixed with neutrophils and cell debris often centered on hair shaft fragments. The latter also often contained endothrix arthrospores and pale hyphae. Arthrospores and hyphae were highlighted with PAS and Grocott's methenamine silver stains. With PAS staining, hyphae appeared septate, non-branching, and measured approximately 1.0 um in width.

Contributor's morphologic diagnosis:

Haired skin, dorsal trunk: Moderate, multifocal, subacute, folliculitis/furunculosis with foci of nodular, pyogranulomatous dermatitis, mild, hyperkeratosis and numerous intralesional fungal arthrospores and hyphae (findings consistent with dermatophytosis or ringworm)

Contributor's comment:

Dermatophytosis (or ringworm) infections are relatively common and affect species of farmed and domestic animals. In farmed mink, outbreaks many are relatively rare and have been attributed to Microsporum canis and Trichophyton mentagrophytes infections. In most reports, kits are most frequently and severely affected. Lesions in adult mink are much less common. Morbidity and mortality are generally low but, fungal infection can cause significant damage to pelts, and thus large outbreaks can have a significant financial impact on producers.1,4

Transmission of infection generally occurs via direct contact with infected animals or by fomites contaminated with hair or dandruff from an infected animal. Dermatophytes are keratinophilic and invade actively growing hair and follicular keratin. In most instances, patchy areas of alopecia and scaling are noted. Peripheral papules or erythematous rims generally surround more centrally located areas of clearing and healing.3

In most instances, dermatophytes are well-adapted to their hosts and have a preferential host range likely due to their specific nutritional requirements. In their preferred host, dermatophyte infection often induces minimal host inflammatory response. Many dogs and cats are asymptomatic carriers. Infection with dermatophytes that are not well adapted to a particular animal species may elicit a greater inflammatory reaction. In most cases, infections are self-limiting and healthy, immune-competent animals will eventually eliminate infection. Immunocompromised animals are at a greater risk of chronic and generalized disease. Most dermatophytes can cause zoonotic disease.

The microscopic lesions in this case are quite classic of dermatophytosis and this case is not much of a diagnostic challenge. What makes it interesting, is the identification of the causative agent via gene sequencing. Trichophyton equinum, as the name implies, is typically associated with dermatophytosis in horses with a worldwide distribution. Reports of T. equinum infection in species other than horses is rare and limited to dogs and cats and humans with direct contact with infected horses. We could find no report of T. equinum infection in mink in the literature. Interestingly, near the time this case was diagnosed, another outbreak of dermatophytosis was diagnosed in 3 week old, kits on a different ranch. These were all dark color phase mink and involved seven litters in 2 different sheds. No adult mink developed lesions. All the mink in each affected litter were euthanized. Microscopic lesions were identical to that described above and T. equinum was isolated from lesions. Testing for Aleutian disease in animals from both ranches was negative and there was no evidence of concurrent or underlying disease in any of the mink examined.

In both instances, culling of infected animals resulted in control of infection and no new cases were reported. The origin of the T. equinum infection in both these ranches remains a mystery. The first case involving the adult pastel mink may have been the result of infection arising from the source farm. However, the source of infection in the second outbreak involving the mink kits is unknown. There were 2 different ranches with no close contact. Contaminated straw or wood-shaving bedding and transmission from handlers were suggested possibilities. However, the bedding used had never been stored or been in direct contact with horses and no animal handlers on the ranch had lesions consistent with dermatophytosis. Contact with potentially infected cats and dogs and the ranch mink not considered likely.

Contributing Institution:

Department of Pathology/Microbiology

Atlantic Veterinary College, University of Prince Edward Island

JPC diagnosis:

Haired skin: Dermatitis, folliculitis, and furunculosis, pyogranulomatous, multifocal, severe, with numerous endothrix and ectothrix arthrospores and hyphae.

JPC comment:

The contributor provides a concise summary on this case of dermatophytosis in mink, and subsequently published this case in 2015.7 There are a number of different species specific dermatophytes that affect domestic species, with occasional exceptions. There are more than 30 species of dermatophytes that affect dogs and cats, but relatively few consistently cause infection and disease. Microsporum canis, Microsporum persicolor, Trichophyton spp., Trichophyton erinacei, and Microsporum gypseum are the most often implicated agents in these species, with dogs occasionally being infected by multiple species of dermatophyte.6

Contrary to naming convention, M. canis is most commonly associated with cats. Trychophyton mentagrophytes is typically acquired from small rodents, and M. gypseum is assumed to be acquired from outdoor activities involving digging or rooting, since M. gypseum is saprophytic. In the event of disruption of the stratum corneum, fungal arthrospores adhere to keratinocytes and migrate to the follicular orifice. Through production of keratinolytic enzymes, endoproteases, and exoproteases, dermatophytes are able to hydrolyze keratin, penetrate the hair shaft, and avoid some of the body's host defenses and sometimes UV light.5

During the conference, there was discussion about culturing fungi. While Sabouraud's dextrose agar and potato-dextrose agar are commonly used for some species, dermatophyte test medium (DTM) is most commonly used for culturing dermatophytes. While most fungi metabolize carbohydrates, dermatophytes use nitrogen sources (keratin, proteins, amino acids) and produce alkaline byproducts. DTM contains Sabouraud's agar for a nutrient source, cycloheximide as a fungicide to prevent saprophytic fungal growth, an antibiotic (often chloramphenicol) to prevent bacterial growth, and phenol red to signal alkaline product production.2

During discussion about which species of dermatophytes typically affect which animals, the moderator introduced most of the group to the term fossorial, characterizing animals that dig and burrow. The analogous adjective to describe tree dwelling animals is arboreal. The discussion was enjoyed by all.

References:

1. Bildfell RJ, Hedstrom OR, and Dearing PL. Outbreak of dermatophytosis in farmed mink in the USA. Vet Rec. 2004; 155:746-748.

2. Chengappa MM, Pohlman LM. Dermatophytes. In: McVey DS, Kennedy M, Chengappa MM, eds. Veterinary Microbiology, 3rd Ed. Ames, IA:John Wiley and Sons. 2013:324.

3. Gross TL, Ihrke PJ, Walder EJ, Affolter VK, eds. Pustular and nodular disease without adnexal destruction. In: Skin Diseases of the dog and cat: Clinical and histopathologic diagnosis. 2nd ed. Blackwell Publishing Company. 2005:406-419.

4. Hagen KW, Gorham JR. Dermatomycosis in fur animals: Chinchilla, ferret, mink and rabbit. US Department of Agriculture. Jan 1972.

5. Maudlin EA, Peters-Kennedy J. Integumentary System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals, Vol 1, 6th Ed. St. Louis, MO:Elsevier. 2016:649.

6. Moriello KA, DeBoer DJ. Dermatophytosis. In: Greene CE, ed. Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat, 4th Ed. St. Louis, MO:Elsevier. 2012:388-390.

7. Overy DP, Marron-Lopez F, Muckle A, et al. Dermatophytosis in farmed mink (Mustela vison) caused by Trichophyton equinum. J Vet Diag Invest. 2015; 27(5):621-626.