Signalment:

11-year-old female spayed Maine coon cat, (

Felis cats).The cat was presented to a local emergency clinic for acute onset of tetraplegia. Neurologic examination revealed normal cranial nerve function, deep pain sensation in all limbs, hindlimb hyperreflexia, and forelimb hyporeflexia, consistent with a C6-T2 spinal cord lesion. The neck was non-painful with normal range of motion. Cervical and thoracic radiographs were unremarkable. The cats neurologic status deteriorated overnight, with worsening forelimb hyporeflexia and loss of deep pain sensation in the left forelimb. A guarded prognosis was given, and the owners elected euthanasia and subsequent necropsy.

Gross Description:

Transverse sectioning of the spinal cord revealed multiple asymmetric brown-grey foci of malacia and hemorrhage, extending from C4-T2. The vertebrae and intervertebral discs were grossly normal.

Histopathologic Description:

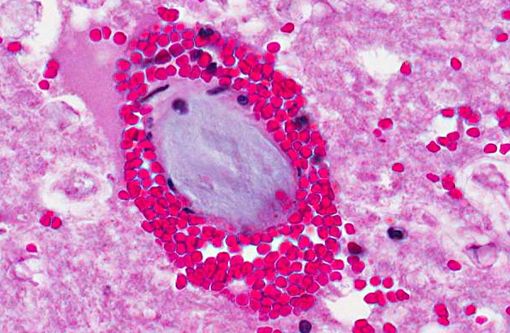

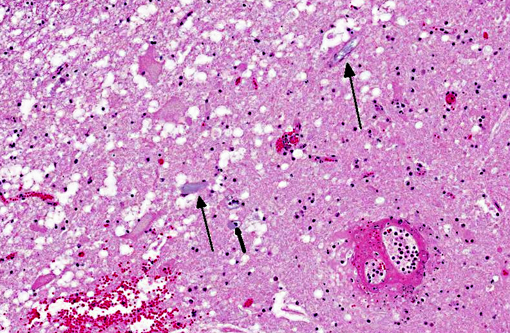

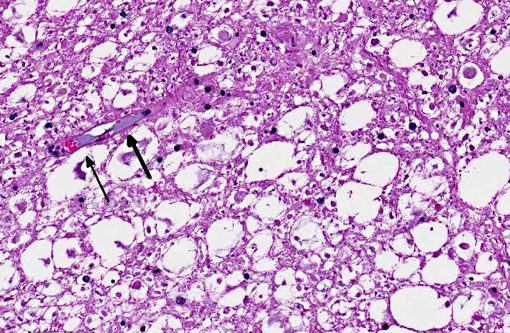

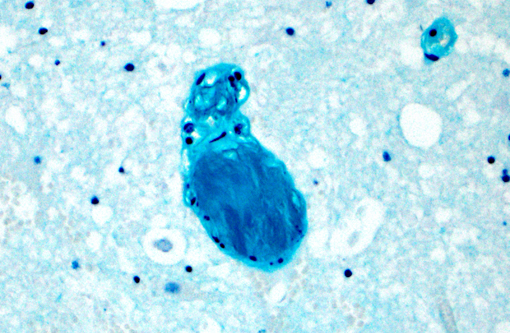

Spinal cord, caudal cervical to cranial thoracic: Affecting up to 75% of the grey and white matter, and most severely affecting the ventral horns and ventral funiculi, are multiple asymmetric foci of malacia characterized by parenchymal vacuolation, hemorrhage, and neuronal necrosis and loss (infarcts). The ventral spinal artery and numerous intramedullary arteries and veins contain luminal amorphous blue-grey material (fibrocartilaginous emboli). Vessel walls are rarely disrupted by brightly eosinophilic fibrillar material and cellular debris (fibrinoid vascular necrosis). Within malacic areas, blood vessels are surrounded by low to moderate numbers of neutrophils that multifocally extend into the surrounding meninges and neuroparenchyma (neutrophilic meningomyelitis) and glial cells are mildly increased in number. Adjacent white matter tracts contain large regions of myelin sheath dilation with numerous swollen axons (spheroids) and rare myelomacrophages (Wallerian degeneration). Within the ventral dura mater are multifocal basophilic concretions (dural mineralization).

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Spinal cord (caudal cervical to cranial thoracic): Severe multifocal acute myelomalacia with intravascular fibrocartilaginous emboli, secondary

neutrophilic meningomyelitis, gliosis, and Wallerian degeneration.

Lab Results:

Brain slices tested negative for rabies virus antigen via immunofluorescence.

Condition:

Fibrocartilaginous embolism

Contributor Comment:

Fibrocartilaginous embolism (FCE), though well-documented in dogs, is considered an uncommon cause of spinal cord disease in cats(4) and has been reported in numerous other species including sheep, pigs, horses, turkeys, mustelids, and humans.(2) Affected cats are non-painful and develop peracute to acute, usually asymmetric, spinal cord-related signs that are non-progressive beyond the first 24-48 hours.(2,5,7) While definitive diagnosis requires histopathologic examination, a presumptive diagnosis may be made antemortem based on history, clinical examination and MRI findings, and exclusion of other causes of myelopathy. Resolution of clinical signs, in the absence of specific therapy, is also highly suggestive of FCE.(4)

The myelomalacia seen in cases of FCE results from occlusion of the blood supply to the spinal cord by fibrocartilaginous emboli, which are thought to originate from the nucleus pulposus of the intervertebral disk.(4,5,7) It is uncertain how the disk material enters the vasculature. Several theories have been proposed, including: 1) penetration of disk material into spinal vessels (e.g. due to trauma), 2) entry into a common blood supply of the intervertebral disk and spinal cord (e.g. remnant embryonic vessels or neovascularization), 3) entry into an anomalous arteriovenous communication, or 4) herniation of disk material into an adjacent vertebral body, allowing entry into the vertebral venous sinus.(1,2,4,5,7)

The distribution and extent of the myelomalacia depends on the size, location, and number of affected blood vessels. Spinal arteries have extensive anastomoses, thus the presence of spinal cord infarcts is consistent with simultaneous occlusion of multiple vessels.(6) Typical histopathologic findings, as seen in this case, include myelomalacia and fibrocartilaginous emboli within leptomeningeal and/or intramedullary blood vessels. Fibrocartilaginous emboli have been described in both arteries and veins, though often the type of vessel affected cannot be definitively identified.(6) While emboli may be evident on routine histologic examination, their identification can be enhanced with Giemsa, toluidine blue, or alcian blue histochemical stains.(7)

JPC Diagnosis:

Spinal cord: Infarcts, multifocal to coalescing, extensive, with wallerian degeneration, hemorrhage and numerous fibrocartilagenous emboli.

Conference Comment:

The contributor provides a concise, thorough summary of the clinical presentation and pathogenesis of fibrocartilagenous embolism. Although FCE is definitively diagnosed via histopathology, a presumptive diagnosis can sometimes be made on the basis of history, clinical signs, a thorough physical and neurologic examination and imaging such as MRI. Differential diagnoses for FCE include causes of acute, asymmetrical paresis such as trauma, spinal cord or vertebral neoplasia, diskospondylitis, intervertebral disk disease, aortic thromboembolism and bacterial, viral or parasitic infections.(1,2,8) In contrast to most of these conditions, however, animals with FCE are typically non-painful on spinal palpation and clinical signs are non-progressive after the first 24-48 hours.(1,2,4)

Metabolic and degenerative disorders as well as toxicities that affect the brain and spinal cord and may result in a similar clinical presentation, but unlike FCE, these conditions generally exhibit a symmetrical distribution. For example, bilaterally symmetrical polioencephalomalacia is observed secondary to dietary thiamine deficiency in carnivores, while lead toxicity can occasionally cause symmetrical laminar cortical necrosis in cattle. A focal, symmetrical poliomyelomalacia of unknown etiology is reported in sheep, goats, pigs and Ayrshire calves, while polioencephalomalacia (PEM) is well described in ruminants; salt toxicity in swine also causes similar lesions. In horses the ingestion of neurotoxin repin, from the yellow star thistle (

Centauea solstitialis) or Russian knapweed (

Centaurea repens), induces symmetrical malacia of the pallidus and substantia nigra, while thiaminase from bracken fern (

Pteridium sp.) and horsetail (

Equisetum arvense) results in bilaterally symmetrical necrosis of the periventricular gray matter.(3)

References:

1. Abramson CJ, Platt SR, Stedman NL. Tetraparesis in a cat with fibrocartilagenous emboli. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2002;38:153-156.

2. Coradini M, Johnstone I, Filippich LJ, Armit S. Suspected fibrocartilaginous embolism in a cat. Aust Vet J. 2005;83:550-551.

3. Maxie MG, Youssef S. Nervous system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals. 5th ed. Vol. 1. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2007:283-455.

4. Mikszewski JS, Van Winkle TJ, Troxel MT. Fibrocartilaginous embolic myelopathy in five cats. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2006;24:226-233.

5. Negrin A, Schatzberg S, Platt S. The paralyzed cat: neuroanatomic diagnosis and specific spinal cord diseases. J Feline Med Surg. 2009;11:361-372.

6. Summers BA, Cummings JF, de Lahunta A. Degenerative diseases of the central nervous system. In: Veterinary Neuropathology. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1995:246-249.

7. Vandevelde M, Higgins RJ, Oevermann A. Vascular disorders. In: Veterinary Neuropathology: Essentials of Theory and Practice. Ames, IA: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012:44-45.Â