Signalment:

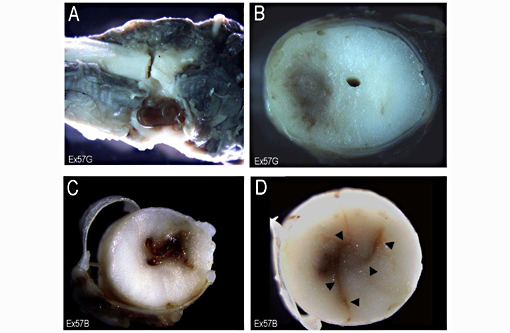

Gross Description:

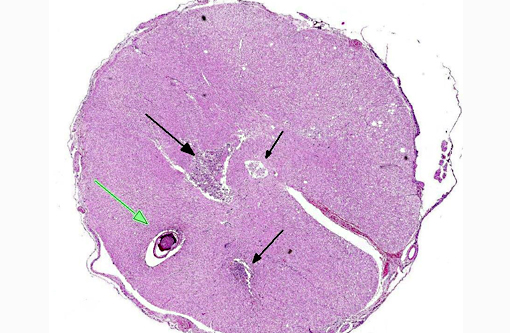

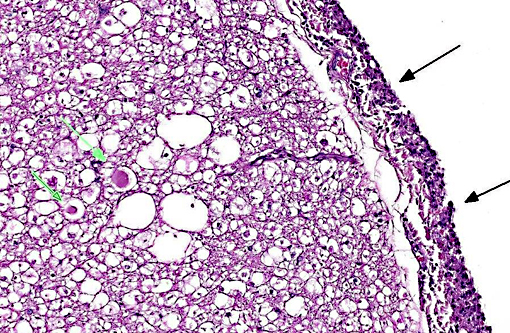

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Carnivores are infected by ingestion of the beetles or a variety of paratenic hosts (birds, lizards, mice, rabbits etc.). In the carnivore host, the infective larvae penetrate the gastric mucosa and migrate within the walls of the gastric arteries to the thoracic aorta. About 3 months post-infection the larvae leave the aorta and migrate to the esophagus where they incite the development of fibro-inflammatory tissue (granulomas) as they mature to adults over the next 3 months. Lesions associated with S. lupi infestation are mainly due to migration and persistence of the parasite in tissues. Esophageal nodular masses (granulomas) and aortic scars and aneurysms are the most common lesions. Other lesions include spondylitis and spondylosis of the caudal thoracic vertebrae, neoplastic transformation of the esophageal granulomas, hypertrophic osteopathy, and aberrant migration into a wide variety of tissues including thoracic viscera, GIT, urinary system and subcutaneous tissue.(5)

More recently, several reports from Israel and South Africa describe aberrant migration into the spinal cord.(1,2,3) In one report (n=4) S. lupi was located in the extradural space and elicited signs typical of thoracolumbar IVD prolapse or spinal trauma.(2) In the remaining cases (n=5), tracts were present within the spinal cord as in the two cases used here.(2,3) Although confirmation of the diagnosis is difficult in cases which recover, the neurologists at the Veterinary School of the Hebrew University estimate that in the past 2-3 years, approximately 10-15 cases are seen annually (Dr. Orit Chai, personal communication). The reason for the increase in the occurrence of this form of canine spirocercosis is unknown but it may in part be attributable to failure in making the correct diagnosis in the past. Currently, a tentative diagnosis is based on the neurological signs, eosinophilic CSF pleocytosis and evidence of S. lupi infection in other tissues (by thoracic radiography, esophagoscopy and fecal floatation). The presenting signs of an acute nonsymmetrical paraparesis / plegia and high CSF eosinophil counts, observed in the present case, are similar to previously reported spinal intramedullary spirocercosis cases.(1)

The cause of aberrant migration of S. lupi is unknown. It has been suggested that aberrant migration occurs when a worm in the thoracic arterial wall enters the intercostal arteries and through their spinal branches arrives at the extradural space. To enter the spinal cord it must then further penetrate the dura mater and the leptomeninges. The location reported in most intradural and extradural cases is T4-L1. In this region the aorta lies closely parallel to the vertebral column and the intercostal arteries supply the spinal branches that enter the spinal canal via the intervertebral foramina.(3)

Verminous encephalomyelitis may arise from aberrant wanderings of a parasite within its normal host (e.g., Dirofilaria immitis in the CNS of dogs and cats and Strongylus vulgaris in the brain of horses); or more commonly, infection of an aberrant host (e.g., Paralephastrongylus tenuis, the meningeal worm of white-tailed deer infesting sheep, goats and other herbivores). Other than regions where S. lupi is prevalent, cerebrospinal helminthosis is uncommon in dogs and cats. Nematodes, which may cause aberrant migration into the CNS of dogs include Angiostrongylus cantonensis in Australia, Angiostrongylus vasorum and Dirofilaria immitis.(6) There is a report of neurologic dysfunction in 3 dogs due to intracranial hemorrhage from consumptive coagulopathy associated with Angiostrongylus vasorum infection of the lung.(3)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

The contributor provides an excellent overview of the complex pathogenesis of Spirocerca and appropriately conveys the tremendous variety of lesions associated with infection. Of significance is the pathognomonic lesion of thoracic spondylitis and its ability to induce malignant transformation, with esophageal fibrosarcoma or osteosarcoma being most characteristic.(7) This ability is not exclusive to Spirocerca, however. The acronym SOCCS-T is often used at JPC to facilitate remembering the following neoplasm-inducing parasites: Spirocerca lupi, Opisthorchis felineus (cholangiocarcinoma in cats and people), Cysticercus fasciolaris (hepatic sarcoma in rats), Clonorchis sinensis (cholangiocarcinoma in cats and people), Schistosoma hematobium (transitional cell carcinoma of urinary bladder in people) and Trichosomoides crassicauda (papillomas of rat urothelium).

Just as the contributor noted, it is the extensive migration of Spirocerca which most commonly causes lesions, as was the case in this dramatic example. Up to 80% of the section of spinal cord was affected in some slides, leading participants to speculate on how rapid the migration must have occurred to cause such extensive lesions in a relatively short period of time. Conference participants also discussed the clinicopathologic findings of pleocytosis, along with elevated neutrophils, eosinophils and protein, as expected findings of a cerebrospinal fluid analysis in this case. This is to contrast with an albuminocytologic dissociation, in which elevated protein levels does not accompany pleocytosis (seen with neoplastic or degenerative diseases such as Guillain-Barre syndrome in people).

References:

1. Chai O, Shelef I, Brenner O, Dogadkin O, Aroch I, Shamir MH. Magnetic resonance imaging findings of spinal intramedullary sprocercosis. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2008;49:456-9.

2. Du Plessis CJ, Keller N, Millward IR. Aberrant extradural spinal migration of Spirocerca lupi: four dogs. J Small Anim Pract. 2007;48:275-278.

3. Dvir E, Perl S, Loeb E, et al. Spinal intramedullary aberrant Spirocerca lupi migration in three dogs. J Vet Intern Med. 2007;21:860-864.

4. Garosi LS, Platt SR, McConnell JF, Wray JD, Smith KC. Intracranial hemorrhage associated with Angiostrongylus vasorum infection in three dogs. J Small Anim Pract. 2005;46:93-99.

5. Mazaki-Tovi M, Baneth G, Aroch I, et al. Canine spirocercosis: Clinical, diagnostic, pathologic and epidemiologic characteristics. Vet Parasitol. 2002;107:235-250.

6. Summers BA. Inflammatory diseases of the central nervous system. In: Summers BA, Cummings JF, de LaHunta A, eds. Veterinary Neuropathology. St. Louis, MO: Mosby-Year Book; 1995:159-162.

7. Van der Merwe LL, Kirberger RM, Clift S, Williams M, Keller N, Naidoo V. Spirocerca lupi infection in the dog: a review. Vet J. 2008;176(3):294-309.