Signalment:

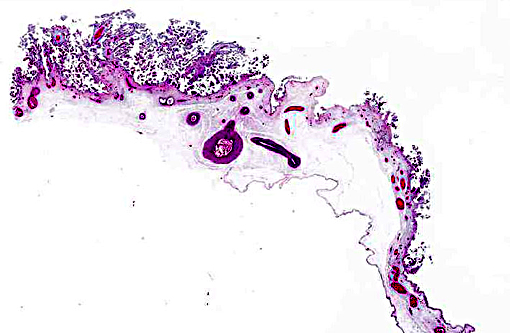

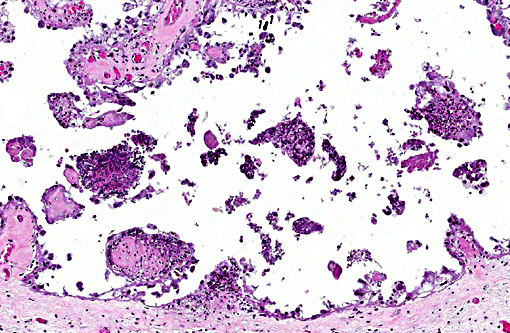

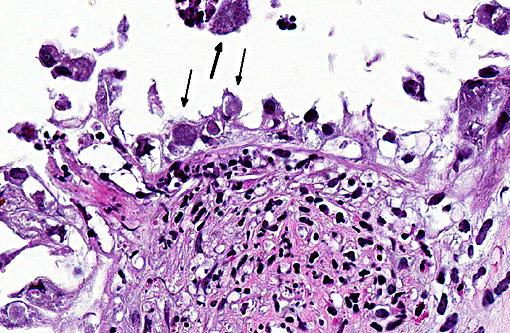

Histopathologic Description:

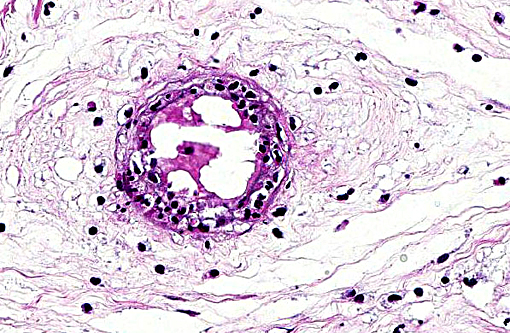

Margination of neutrophils as well as exocytosis is observed in blood vessels in the lamina propria. Occasional fibrin thrombi are present. Cytoplasm of many remaining trophoblasts is distended with coccobacilli.

Morphologic Diagnosis:

1. Marked multifocal subacute necrotic and neutrophilic placentitis with intralesional coccobacilli.

2. Moderate to marked multifocal subacute neutrophilic vasculitis.

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

During infection, the majority of the organisms localize in cotyledons, placental membranes, and in allantoic fluid. Early infection of the placenta begins in intercotyledonary erythrophagocytic trophoblasts followed by replication in adjacent chorioallantoic trophoblasts.(1) After replication, there is necrosis of trophoblasts with release of massive numbers of organisms into the uterine lumen.(1) The usual source of infection for cattle is ingestion of organisms from an aborted fetus or placenta, or contaminated uterine discharge.(7)

This case is unusual in that abortion was the result of administration of the vaccine strain (RB51) of B. abortus. It has been shown that vaccinating pregnant cattle with RB51 can result in rare placentitis and preterm expulsion of the fetus.(5) Vaccination of pregnant cattle is ill-advised. Therefore, vaccination is limited to young, non-pregnant cattle. In spite of recommendations, instances of fetal wastage occur.(2) In the present case, the fact the pregnancy status was unknown resulted in fetal loss. It should be noted that animal workers are at risk of infection by B. abortus when assisting parturition or handling infected tissues from these animals.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Necrotizing placentitis with intratrophoblastic bacteria is typical for, but not unique to, B. abortus, and would be expected to be much more severe in naturally occurring disease. Gross lesions commonly consist of a necrotizing placentitis with thick brown and/or bloody exudates. In general, gross and microscopic lesions can be very similar with the various agents of bacterial abortion. Differential diagnosis for bacterial placentitis with intratrophoblastic bacteria include other gram negative organisms such as Coxiella burnetii, where infected trophoblasts typically have a more foamy vacuolated appearance, and Chlamydophila abortus, where placental vasculitis would be very prominent. C. burnetti is more common in goats and is rare in the U.S., and C. abortus is more common in sheep. The gram-positive organism Listeria monocytogenes was also discussed, which, in addition to abortion, results in fetal septicemia and the presence of foci of necrosis in many organs. Other bacterial causes of abortion include leptospirosis, which would not result in necrotizing placentitis; and Campylobacter sp., which more commonly results in early embryonic death but can result in abortion with similar gross and histologic placental lesions as brucellosis, but lesions are generally less severe.(3)

There are both smooth and rough strains of Brucella spp., with rough strains lacking the expression of O side chain on the lipo-polysaccharide (LPS), and include the RB51 vaccine strain. Smooth and rough strains enter phagocytic cells, preferably macrophages, differently and the rough strain is more rapidly targeted to the phagolysosomal compartment and is generally unable to replicate, whereas smooth strains are capable of intracellular replication within the phagosome. Virulent Brucella spp. employ multiple mechanisms to detoxify free radicals in order to survive in the phagosome, including expression of superoxide dismutases. Brucella spp. have also adapted mechanisms to avoid the innate immune system, such as decreased stimulatory activity of TLR4 receptors, being devoid of structures such as pili, fimbriae and capsules that would stimulate pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), as well as prevention of phagosome-lysosome fusion and inhibition of macrophage apoptosis.(4) Primary routes of infection are considered to be oral exposure to contaminated fetal membranes and aborted fetuses, and ingestion of contaminated milk. Once the infection is localized within lymph nodes, bacteremia results in extension of infection into multiple organs including the uterus, placenta and mammary glands. When the infection reaches the fetal membranes, bacteria replicate within trophoblast cells, and there is extensive necrosis and exudates as well as endometritis, and abortion is the eventual result.(4)

References:

1. Anderson TD, Cheville NF, Meador VP. Pathogenesis of placentitis in the goat inoculated with Brucella abortus. II. Ultrastructural studies. Vet Pathol. 1986; 23:227-239.

2. Fluegel Dougherty AM, Cornish TE, O'Toole D, Boerger-Fields AM, Henderson OL, Mills KW. Abortion and premature birth in cattle following vaccination with Brucella abortus strain RB51. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2013; 25: 630-635.

3. Foster RA. Female reproductive system and mammary gland. In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2012:1110-1115.

4. Olson SC, Palmer MV. Advancement of Knowledge of Brucella over the past 50 years. Vet Pathol. 2014;51(6):1076-1089.

5. Palmer MV, Cheville NF, Jensen AE. Experimental infection of pregnant cattle with the vaccine candidate Brucella abortus strain RB51: pathologic, bacteriologic, and serologic findings. Vet Pathol. 1996; 33:682-691.

6. Poester FP, Goncalves VS, Paixao TA, Santos RL, Olsen SC, Schurig GG, Lage AP. Efficacy of strain RB51 vaccine in heifers against experimental brucellosis. Vaccine. 2006; 24: 5327-5334.

7. Schlafer DH, Miller RB. Female genital system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 3. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2007: .

8. Schurig GG, Roop RM, Bagchi T, Boyle S, Buhrman D, Sriranganathan N. Biological properties of RB51; a stable rough strain of Brucella abortus. Vet Microbiol. 1991; 28:171-188.