Signalment:

5-year-old female Swedish riding pony, (Equus caballus).The horse was euthanized, and presented for necropsy after traumatic injury to the left hock, with suspected septic bursitis of the left calcaneal bursa and possible bone involvement.

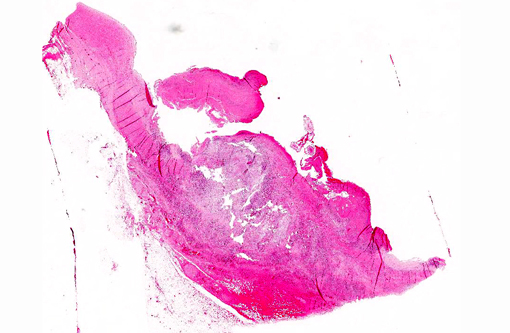

Gross Description:

There is diffuse thickening of the dermis and focal ulceration (approximately 2x2 cm) on the dorsal aspect of the left hock, exposing dry granulation tissue. The calcaneal bursa contains fibrinopurulent and hemorrhagic material and there is hypertrophy and ecchymotic hemorrhages of the synovial membrane.

Within the cranial mesenteric artery, there is a focal area with thickening of the arterial wall and vegetative thrombotic masses attached to the vascular intima with presence of several slender nematode parasites, less than 20 mm in length.

Histopathologic Description:

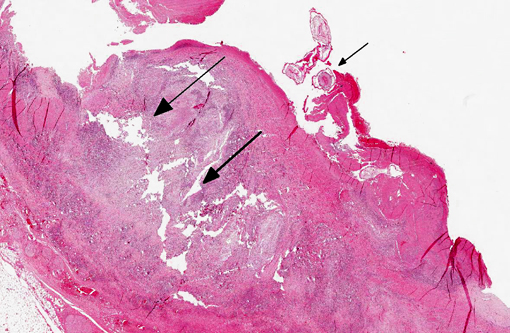

Large muscular artery and surrounding soft tissues: There is a marked inflammatory reaction involving tunica intima, media, and adventitia with multifocal to coalescing infiltrates of a mixed population of inflammatory cells, which in all arterial layers consist of large numbers of plasma cells and lymphocytes, and moderate to large numbers of eosinophils and histiocytes. There is extensive multifocal to coalescing necrosis, predominantly involving the tunica media and intima. Continuous with and disrupting/destructing the endothelial lining of the tunica intima, are extensive depositions of deeply eosinophilic homogenous to finely granular fibrinous masses (thrombi) containing moderate amounts of cellular debris, multifocal accumulations of erythrocytes, neutrophils, and multifocal sheets of large numbers of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and moderate numbers of eosinophils (with focal areas of mineralization present in some sections). The tunica intima also shows thickening, fibrosis and multifocal small hemorrhages.

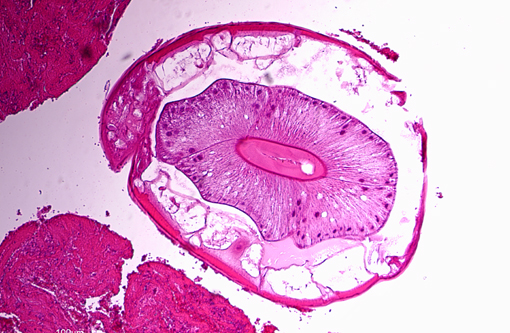

On the luminal side of the intima and partially embedded within the thrombotic masses, are several metazoan parasites (measuring approximately between 0.6 and 1.2 mm), covered by a smooth cuticle, and showing a thin hypodermis, platymyarian musculature, and a large intestine with few multinucleated cells and a prominent brush border (strongyle larvae).

In the tunica media, the heavy infiltration of inflammatory cells and areas of necrosis disrupt myocyte alignment and the borders between the tunica media and adventitia and intima. In the tunica adventitia and surrounding soft tissue, the inflammatory infiltrates are predominantly perivascular and lymphoplasmacytic, and there is hyperemia of venules. Moderate to large numbers of slender rod-shaped bacteria are also seen (post-mortem bacterial growth).

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Cranial mesenteric artery: Arteritis, lymphoplasmacytic and eosinophilic, chronic, transmural, severe, with multifocal necrosis, thrombosis and intra-luminal/-lesional strongyle larvae.

Condition:

Strongylus vulgaris

Contributor Comment:

The location and nematode morphology suggest that the presented case represents verminous arteritis caused by Strongylus vulgarism. No parasites were observed in the large intestine, which may have related to the necropsy being performed during winter when intestinal numbers of S. vulgaris are low.(2)

Strongyle nematodes are important gastrointestinal parasites of the horse. Strongyles have a worldwide distribution, and in a recent Italian study, large strongyles (Strongylinea) were the most abundant and most prevalent (34%) equine large intestinal parasites.(10) The three common genera of migratory large strongyles that affect horses (Strongylus edentatus, S. equinus, and S. vulgaris) live as adults in the large intestine of the horse, but have differing migratory larval routes.(11) The adults are found in the colon and cecum, and produce eggs that are passed via the feces and that develop to infective third-stage larvae (L3) outside the host.(11) Ingested L3 of S. vulgaris exsheath in the small intestine, penetrate the intestinal mucosa of the small intestine, colon and cecum, and moult in the submucosa to L4.(7,11) Fourth-stage S. vulgaris larvae then enter small intestinal arteries and migrate to the cranial mesenteric artery and its main branches, which are predilection sites for lesions caused by the larval stages.(7,11) A marked seasonality in proportions of affected arteries and arterial worm burdens have been reported, with the highest numbers encountered during winter.(9) After further development of L4 in the mesenteric circulation, L5 larvae return via the vasculature to the intestine, where nodule formation arise around larvae trapped in the smaller vessels of the intestinal wall, before young adult nematodes are released into the intestinal lumen.(11) The prepatent period for S. vulgaris is 6-7 months.(11)

Histopathologic arterial wall changes from necropsies most often reveal chronic (fibrosis of intima and/or media, with or without mild accumulation of mononuclear inflammatory cells) or chronic active (neutrophils, eosinophils and necrotic foci are also present) arteritis.(8) Severity of inflammatory changes have been shown to be directly related to presence of larvae, which may be entrapped in intimal thrombi, the intima itself, and less commonly in the media or adventitia.(8) Verminous arteritis can be found in necropsies of horses with no history of colic,(7,12) such as in the presented case. However, thromboembolism in the branches of the cranial mesenteric and the ileocaecocolic arteries and ischemia or infarction, interference of gut innervation related to pressure on abdominal autonomic plexuses, and release of toxic products from dying larvae have all been discussed as causes of clinical disease.(7,12)

Pathogenic effects in the large intestine relate to adult worms feeding on mucosal material and incidental damage to blood vessel, but also to disruption of the mucosa associated with the emergence of young adults.(11) Infestation may lead to poor condition and performance, anemia, temporary lameness, intestinal stasis, colic, and rarely intestinal rupture and death.(11)

JPC Diagnosis:

Mesenteric artery: Arteritis, proliferative, eosinophilic and granulomatous, transmural, diffuse, severe, with thrombosis and multiple strongyle larvae.

Conference Comment:

Nematodes of the subfamily Strongylinae (family Strongylidae) are plug feeders or blood suckers commonly found in the cecum and colon of horses and tend to undergo extensive extraintestinal migration.(1) As noted by the contributor, the three major genera of the Strongylinae subfamily are S. vulgaris, S. edentatus and S. equinus. Conference participants briefly discussed the microscopic characteristics associated with the larvae of large strongyles (also known as true strongyles), including platymyarian-meromyarian musculature, prominent lateral cords, a pseudocoelom, and a large, central intestine lined by few multinucleated cells with a prominent brush border.(4) S. vulgaris larvae preferentially migrate up the cranial mesenteric artery, leading to arteritis, thrombosis and, occasionally, segmental colonic necrosis. Aberrant migration into the aorta, renal and coronary arteries is also described.(1,7) Upon ingestion, infective third stage larvae of S. edentatus penetrate the intestinal wall, enter the liver via the portal vein, molt to L4, and migrate through the hepatic parenchyma, causing eosinophilic, neutrophilic and mononuclear inflammation and hemorrhagic/necrotic tracts. Resultant tags of fibrous scar tissue on the hepatic capsule can often be detected as incidental findings on gross necropsy. After leaving the liver via the hepatorenal ligament, larvae travel to the retroperitoneal tissue of the flank. Here they molt to L5 prior to returning to the cecum/colon, where they form nodules and hemorrhagic plaques within the gut wall (one possible cause of hemomelasma ilei) and eventually penetrate the lumen and lay eggs.(1) Aberrant migration of S. edentatus is also occasionally reported as a cause of orchitis in young stallions.(3) S. equinus is less prevalent then either S. vulgaris or S. edentatus and infection is generally clinically insignificant. Exsheathed third stage larvae penetrate into the deep layers of the ileum, cecum and colon, where they produce subserosal nodules. Fourth stage larvae migrate throughout the liver, pancreas and peritoneum, molt to L5, and ultimately return to the cecum/colon, causing mild eosinophilic inflammation.(1)

In contrast to true strongyles, members of the subfamily Cyathostominae feed on intestinal contents and are essentially non-pathogenic as adults, although emergence of histotropic larval stages from the intestinal wall may cause disease. Cyathostomes, also known as small strongyles, can number in the hundreds of thousands in the equine large intestine. Larvae burrow into the submucosa to develop, where they may undergo hypobiosis; emergence of large numbers can cause rupture of the muscularis mucosae with severe inflammation and edema. Clinically, affected horses present with diarrhea, ill-thrift and hypoalbuminemia, while grossly the colonic mucosa may exhibit numerous umbilicated red-black nodules containing encysted larval nematodes.(1) Much like S. vulgaris, the clinical syndrome (larval cyathostomiasis) associated with these infections is typically seasonal in onset, occurring most commonly in younger animals in late winter or early spring.(2) The moderator also pointed out that these small strongyles often exhibit variable degrees of ivermectin and moxidectin resistance, which can confound attempts at control/treatment.(5,6)

References:

- Brown CC, Baker DC, Barker IK. Alimentary system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 2. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:247-249.

- Chapman MR, French DD, Klei TR. Prevalence of strongyle nematodes in naturally infected ponies of different ages and during different seasons of the year in Louisiana. J Parasitol. 2003;89:309-314.

- Foster RA, Ladds PW. Male genital system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 3. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:587.

- Gardiner CH, Poynton SL. Strongyles. In: An Atlas of Metazoan Parasites in Animal Tissues. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 2006:22-24.

- Lyons ET, Tolliver SC, Ionita M, Lewellen A, Collins SS. Field studies indicating reduced activity of ivermectin on small strongyles in horses on a farm in cenral Kentucky. Parasitol Res. 2008;103(1):209-215.

- Lyons ET, Tolliver SC, Kuzmina TA, Collins SS. Critical tests evaluating efficacy of moxidectin against small strongyles in horses from a herd for which reduced activity had been found in field tests in Kentucky. Parsitol Res. 2010;107(6):1495-1498.

- Maxie MG, Robinson WF. Cardiovascular system. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 3. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:89-91.

- Morgan SJ, Stromberg PC, Storts RW, Sowa BA, Lay JC. Histology and morphometry of Strongylus vulgaris-mediated equine mesenteric arteritis. J Comp Pathol. 1991;104:89-99.

- Ogbourne CP. Studies on the epidemiology of Strongylus vulgaris infection of the horse. Int J Parasitol. 1975;5:423-426.

- Stancampiano L, Gras LM, Poglayen G. Spatial niche competition among helminth parasites in horse's large intestine. Vet Parasitol. 2010;170:88-95.

- Taylor MA, Coop RL, Wall RL. Parasites of horses. Endoparasites: Parasites of the digestive system. In: Veterinary Pathology. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2007: 280-284.

- White NA. Thromboembolic colic in horses. Compendium on Continuing Education. 1985;7:S156-S163.