Signalment:

Gross Description:

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Hematocrit 17.4 (37-55%). Reticulocyte count 15,750 (>60,000 indicates regeneration).Â

Serum biochemistry: BUN 70 (7-27 mg/dl), creatinine 4.9 (0.4-1.8 mg/dl), phosphorous 16.1 (2.1-6.3), total protein 4.1 (5.1-7.8 g/dl), albumin 1.0 (2.3-4.0 g/dl).Â

Urinalysis: urine protein 1,253 (10-50 mg/dl), creatinine 76.8 (100-500 mg/dl), protein/creatinine ratio 16.3 (<0.5). Urine culture: no growth.

Coagulation profile: normal PT 7.5 (6.8-10.2 s), slightly prolonged PTT 16.9 (10.7-16.4 s), increased d-dimers 0.28 (<0.2 ug/ml), and decreased platelets 49 (177-398 x 103/ul), consistent with disseminated intravascular coagulation.

Serology: negative for Rickettsia rickettsii, Bartonella spp., Ehrlichia canis, Anaplasma spp., Dirofilaria immitis, and Leptospira spp.; positive for Borrelia burgdorferi (Idexx SNAP-� 4Dx-� test).

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Diagnosis of infection can be determined by a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) that does not react to commercially available Lyme borreliosis vaccines.(8) This ELISA detects the C6 peptide derived from a conserved immunodominant region (IR6) of a segment of a B. burgdorferi surface protein named VlsE (Vmp-like sequence, expressed).(8) Alternatively, Western blot may be used to distinguish between natural and vaccine exposure in dogs by detecting antibodies to OspA or OspB.(3) Minimal evidence exists to support the presence of B. burgdorferi or other bacterial organisms in the kidneys of affected dogs; rare spirochetes have been seen in silver stains.(4) B. burgdorferi DNA is rarely amplified by PCR in renal tissue from affected dogs, and often B. burdorferi antigen is not detected by immunohistochemical staining.(1) It is thought that the lesions seen in Lyme nephritis are due to a sterile immune complex disease.Â

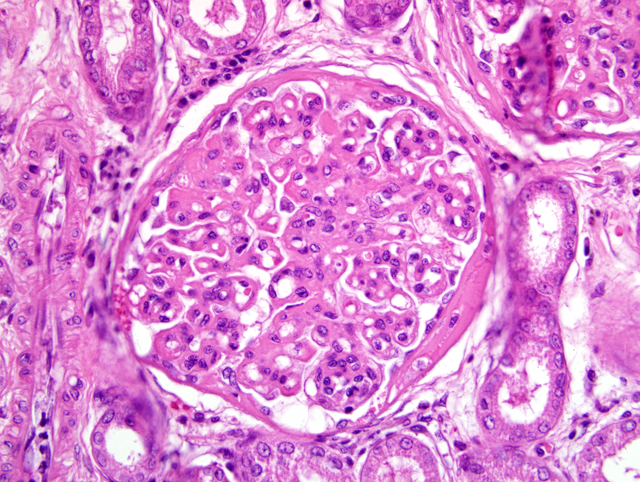

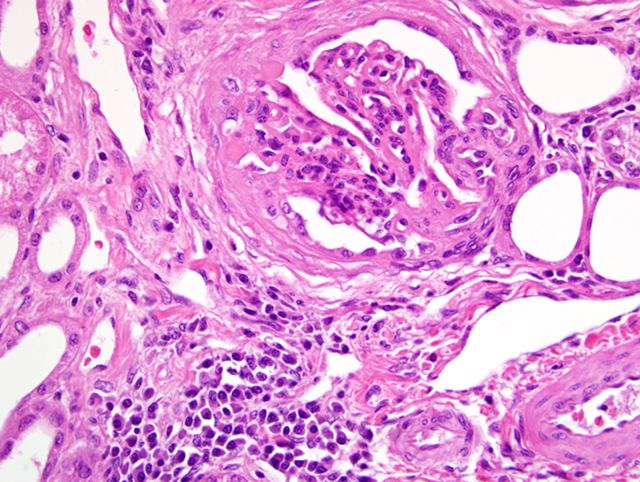

The most common glomerular lesion in Lyme nephritis is membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, with adhesions of glomerular tufts to Bowmans capsule, and often periglomerular fibrosis of Bowmans capsule. The membranous component is the result of immune mediated glomerulonephritis with subendothelial deposits, IgG, IgM, and C3 present along glomerular basement membranes. The proliferative component is due to increased mesangial cell number and influx of inflammatory cells (macrophages and neutrophils). The severe, diffuse glomerular lesions are likely the primary lesion and responsible for subsequent tubular changes including multifocal dilation with necrosis and regeneration. Tubular damage most likely results from cellular hypoxia and/or nephrotoxin exposure due to profound proteinuria; damaged tubules express vimentin. Interstitial fibrosis is often present to some degree, and mild to moderate lymphoplasmacytic inflammation is present throughout the cortex. Arteriolar changes are occasionally noted and include fibrinoid necrosis of small to medium arterioles or deposition of PAS-positive hyaline material in hilar arteriolar walls, lesions commonly associated with renal disease-induced hypertension.(2)

B. burgdorferi is transmitted by Ixodes spp. ticks, which may feed on and cause disease in several species including dogs, horses, cattle, cats and people. The most common manifestation of disease in dogs is polyarthritis, with fewer cases of nephritis, and one case report of myocarditis.(5,9) In addition to arthritis, horses may also develop ocular disease and probably encephalitis, and abortions may be seen in cattle. The tick vector for B. burgdorferi has a two-year life cycle. Larvae and nymphs primarily feed on birds and small mammals; the main mammalian host is the white footed mouse and deer mouse (Peromyscus spp.). Adults primarily feed on white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), which are asymptomatic carriers. Adult ticks must attach to the host for a minimum of 24 hours in order to transmit the bacterium. Deer flies and horse flies may act as mechanical vectors in areas where infection is well maintained in the wildlife population by tick vectors.(9)

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

- Adenoviral hepatitis (infectious canine hepatitis caused by canine adenovirus-1)

- Borreliosis (Lyme nephritis caused by B. burgdorferi)

- Chronic disease (pancreatitis, hepatitis, pyoderma, neoplasia)

- Dirofilariasis (heartworm disease caused by Dirofilaria immitis)

- Hereditary C3 deficiency

- Immune-mediated disease (hemolytic anemia, polyarthritis, systemic lupus erythematosis)

- Polyarteritis

- Prostatitis

- Pyometra

This case also stimulated conference participants to review the proposed pathogenesis of immune-complex glomerulonephritis. Classically, immune-complex glomerulonephritis is thought to result from prolonged antigenemia, with circulating antigen equivalent to or in slight excess of circulating antibody; this results in the formation of soluble antigen-antibody complexes that deposit in glomerular capillaries within or on either side of the glomerular basement membrane (GBM), where they initiate complement fixation and cause elaboration of neutrophil chemotaxins (e.g. C3a, C5a, and C567). Neutrophils release proteinases, arachidonic acid metabolites, oxygen-derived free radicals, and hydrogen peroxide, damaging the GBM and inciting monocyte infiltration.(7) There is some controversy concerning the significance and importance of soluble immune complexes in the pathogenesis of glomerulonephritis; several investigators suggest the presence of immune complexes within and around the GBM may be secondary to the damage on the glomerulus rather than the inciting stimulus for the glomerular lesions.(6)

References:

2. Dambach DM, Smith CA, Lewis RM, Van Winkle TJ: Morphologic, immunohistochemical, and ultrastructural characterization of a distinctive renal lesion in dogs putatively associated with Borrelia burgdorferi infection: 49 cases (1987-1992). Vet Pathol 34:85-96, 1997

3. Gauthier DT, Mansfield LS: Western immunoblot analysis for distinguishing vaccination and infection status with Borrelia burgdorferi (Lyme disease) in dogs. J Vet Diagn Invest 11:259-265, 1999

4. Hutton TA, Goldstein RE, Njaa BL, Atwater DZ, Chang Y, Simpson KW: Search for Borrelia burgdorferi in kidneys of dogs with suspected Lyme nephritis. J Vet Intern Med 22:860-865, 2008

5. Levy SA, Duray PH: Complete heart block in a dog seropositive for Borrelia burgdorferi. Similarity to human Lyme carditis. J Vet Intern Med 2:138-144, 1988

6. Maxie MG, Newman SJ: Urinary system. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 2, pp. 451-462. Elsevier Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 2007

7. Newman SJ, Confer AW, Panciera RJ: Urinary system. In: Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease, ed. McGavin MD, Zachary JF, 4th ed., pp. 628-641. Mosby Elsevier, St. Louis, MO, 2007

8. OConnor TP, Esty KJ, Hanscom JL, Shields P, Philipp MT: Dogs vaccinated with the common Lyme disease vaccines do not respond to IR6, the conserved immunodominant region of the VlsE surface protein of Borrelia burgdorferi. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 11:458-462, 2004

9. Thompson K. Inflammatory diseases of joints. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 1, pp. 166-167. Elsevier Saunders, Philadelphia, PA, 2007