CASE III: 10A089 (JPC 4002933).

Signalment: 8.74-year-old female Indian Rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta), nonhuman primate.

History: This animal was part of a routine SHIV study, at the end of which it was euthanized for tissue collection. Clinically normal animal, incidental finding at necropsy.

Gross Pathology: A 5.5 X 4.5 X 3 cm, irregularly round, whitish, sessile, expansile, soft mass, with bosselated but smooth external surface and no adhesions to the adjacent structures, is identified on the right ovary. The cut surface is light tan-to-beige, smooth and relatively soft, with a few irregularly- shaped, non-intercommunicating cyst-like structures. The left ovary along with the rest of genital tract is grossly normal. All other organs are within normal limits.

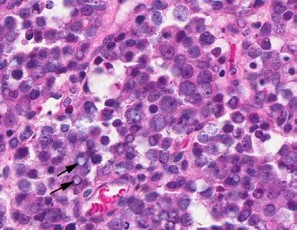

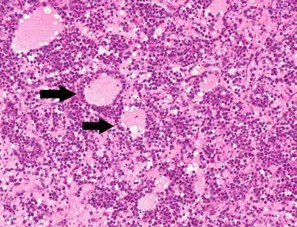

Contributor?s Histopathologic Description: Right ovary: About 98% of the ovarian parenchyma is completely effaced and replaced by an unencapsulated, infiltrative, and densely to sparsely cellular neoplasm, compressing preexisting ovarian stroma and pre-antral and antral follicles present in the periphery between the neoplasm and ovarian tunica albuginea , and sparing the oviduct (not present in all slides). Neoplastic cells are arranged in sheets, islands, nests, strands, and cords of round-to-polygonal cells (germ cells) separated by fine fibrovascular stroma, which is expanded in many areas by varied amount of slightly eosinophilic lacy-to- amorphous material (secretory protein/edema). Neoplastic cells have distinct to indistinct cell borders, minimal-to-abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm, large round, centrally located, and vesicular nuclei with finely stippled chromatin and a single magenta nucleolus. Multifocally, neoplastic cells surround numerous variably-sized cyst-like spaces that are usually filled with proteinaceous fluid and occasionally contain small amount of lacy material admixed with a few neoplastic cells, lymphocytes, neutrophils and cellular debris and tend to form binucleated-to- multinucleated cells with up to 5 nuclei. Mitotic figures are common (average 3-4 per HPF), some of which are atypical, and there is marked anisocytosis and anisokaryosis. Interspersed among neoplastic cells are multifocal accumulations of lymphocytic infiltrate, clusters of interstitial gland cells with large vacuolated cytoplasm, variably distinct borders, and central-to- eccentric nucleus, scattered single cell necrosis, low numbers of plasma cells and neutrophils, and occasional eosinophils. Variably-sized masses of neoplastic cells are present within lymphatic vessels, and there are focal areas at the periphery of the mass where neoplastic cells tend to breach the adjacent tunica albuginea. Edema and some mineralized foci are also noted.

Immunohistochemistry:

- Vimentin, multifocally weakly positive.

- Cytokeratin, negative.

- Alpha-fetoprotein, negative.

- CD3, negative for neoplastic cells; positive for lymphocytic infiltrate.

Contributor?s Morphologic Diagnosis: Right ovary: dysgerminoma, rhesus monkey (Macaca mulatta).

Contributor?s Comment: An incidental finding of unilateral ovarian dysgerminoma in a rhesus monkey (macaca mulatta) is examined histologically and immunohistochemically. To our knowledge there is only one documented report of ovarian dysgerminoma in a rhesus m o n k e y . 6 O v a r i a n dysgerminomas and seminomas, their testicular analogue, are germ

cell tumors that arise from primordial germ cells of the ovary and the testis. In female domestic animals, germ cell tumors are limited to germinoma and teratomas, whereas in women and female laboratory animals other ovarian germ cell neoplasms also include: embryonal carcinoma, choriocarcinoma, and endodermal sinus tumor.7 Although rare, ovarian dysgerminomas are reported in a variety of mammals and non-mammalian species, including humans (girls and women)9; non- human primates6; domestic animals7; and wildlife, avian, amphibian and reptilian species and fishes.11 M a c r o s c o p i c a l l y , m i c r o s c o p i c a l l y a n d immunohistochemically changes observed in this case are basically similar to those previously reported in other mammals and lower vertebrates.11,4 Grossly, the neoplasm is usually unilateral but may be bilateral, relatively soft, with smooth external surface, and may have cystic structures on cut surface. Histologically, the neoplasm is usually diffusely densely cellular with focal cystic and mineralized areas and high mitotic index, and neoplastic cells are round to polygonal with granular cytoplasm. Interestingly in this case, the neoplasm is relatively less densely cellular but contains abundant amount of extracellular proteinaceous material consistent with accumulation of protein secretion and/or edema. Although not prominent in this case, some neoplastic germ cells express vimentin in perinuclear pattern, but no expression of cytokeratin, alpha-fetoprotein, or CD3 can be detected by immunohistochemistry. On histopathological examination, differential diagnosis should include any round cell neoplasm, especially lymphosarcoma. In general, ovarian dysgerminomas are considered to be nonfunctional in all species; however, they can be hormonally active.2

More recently, stem cell markers such as OCT3/4, SOX2, and growth differentiation factor 3 (GDF3) have been reported to be expressed variably in germ cell tumors.4 Unfortunately, these markers expression could not be investigated in this case. The exact cause of dysgerminomas has not been determined, but more recent molecular studies3 have implicated loss of function with potential tumor suppressor gene TRC8/ RNF-139 as a possible cause in humans. This would shed some light on the molecular pathways involved in the pathogenesis of this neoplastic condition, which remains to be determined.

JPC Diagnosis: Ovary and oviduct: Dysgerminoma.

Conference Comment: Dysgerminomas are considered potentially malignant, although they metastasize in only 10-20% of cases. Ovarian dysgerminomas are considered to arise from the follicular oocytes or testicular homologues within the ovary, in addition to primordial germ cells. The neoplastic cells share ultrastructural similarity to normal fetal oogonia. These neoplasms typically exhibit cytoplasmic and membranous immunoreactivity for placental alkaline phosphatase (PLAP), which is also positive in other malignant germ cell tumors, and is mainly useful in differentiating it from non-germ cell tumors such as clear cell carcinoma, malignant lymphoma, and granulosa cell tumor. Dysgerminomas also show membrane staining for CD117 (c-kit), which helps to differentiate them from embryonal carcinomas and yolk sac neoplasms. The stem cell-related protein Oct-4 mentioned by the contributor is also positive in embryonal carcinomas, although it is highly sensitive for dysgerminoma. However, podoplanin, which exhibits strong cytoplasmic immunoreactivity for dysgerminoma, can be used to rule out embryonal carcinoma, in which it is negative. The oncofetal glycoprotein alpha-fetoprotein mentioned by the contributor as negative for dysgerminoma is a positive marker for yolk sac tumors. Many of these immunohistochemical markers are not widely available for veterinary diagnostics; therefore, CD117 may be the most useful and available marker to definitively prove dysgerminoma.10

Dysgerminomas have been reported in related maned wolves (Crysocyon brachyurus), which may have a genetic predisposition to these neoplasms, as well as in mountain chicken frogs (Leptodactylus fallax). In horses, dysgerminoma has been reported as a cause of hypertrophic osteopathy, which is more commonly associated with concurrent thoracic disease.1,5,8

Contributor: Tulane National Primate Research Center

Division of Comparative Pathology 18703 Three Rivers Road Covington, LA 70433-8915

References:

1. Chandra AM, Woodard JC, Merritt AM. Dysgerminoma in an Arabian filly. Vet Pathol. 1998;35 (4):308-11.

2. Gelberg HB, McEntee K. Feline Ovarian Neoplasm.

Vet Pathol. 1985;22:577-576.

3. Gimelli S, Beri S, Drabkin HA, et al. The tumor suppressor gene TRC8/RNF139 is disrupted by a constitutional balanced translocation (8;22) (q24.13;q11.21) in a young girl with dysgerminoma. Molecular Cancer. 2009;8:52.

4. Goplan A, Dhall D, Olgac S, et al. Testicular mixed g e r m c e l l t u m o r s : a m o r p h o l o g i c a l a n d immunohistochemical study using stem cell markers, OCT3/4, SOX2 and GDF3, with emphasis on morphologically difficult-to-classify areas. Modern Pathology. 2009;22:1066-1074.

5. Fitzgerald SD, Duncan AE, Tabaka C. Ovarian dysgerminomas in two mountain chicken frogs (Leptodactylus fallax). J Zoo Wildlife Med. 2007;38(1): 150-153.

6. . Holmberg CA, Sesline D, Osburn, B. Dysgerminoma in a Rhesus Monkey: Morhologic and Biological Features. J. Med. Primatol. 1978;7:53-58.

7. Maclachnan NJ, Kennedy PC. Tumors of the genital systems. In: Meuten D, ed. Tumors in Domestic Animals. 4th ed. Ames, IA; Blackwell Publishing: 2002;547-557.

8. Munson L, Montali RJ. High prevalence of ovarian tumors in maned wolves (Chrysocyon brachyurus) at the National Zoological Park. J Zoo Wildlife Med. 1991;22(1):125-129.

9. Pectasides D, Pectasides E, Kassanos D. Germ cell tumors of the ovary. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2008;34(5): 427-41.

10. Rabban JT, Soslow RA, Zaloudek CZ. Immunohistology of the female genital tract. In: Dabbs DJ, ed. Diagnostic Immunohistochemistry, Theranostic and Genomic Applications. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders-Elsevier; 2010:737-8.

11. Strunk A, Imai DM, Osofsky A, et al. Dysgerminoma in an eastern rosella (Platycercus eximius exemius). Avian Diseases. 2011;55:133-138.