Signalment:

Adult male cynomolgus macaque (

Macaca fascicularis).This macaque was

in a study to determine the efficacy of a novel therapeutic drug for treating

Marburg virus (MARV) infection. All of the monkeys in this study were

inoculated subcutaneously with MARV and then once daily intramuscular

treatments with either saline (control group) or different doses of the

therapeutic drug (experimental groups) began. This animal was in one of the

experimental groups and it was found dead on Day 11 after viral challenge.

This monkey was

part of a research project conducted under an IACUC approved protocol in

compliance with the Animal Welfare Act, PHS Policy, and other federal statutes

and regulations relating to animals and experiments involving animals. The

facility where this research was conducted is accredited by the Association for

Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care, International and

adheres to principles stated in the 8

th edition of the Guide

for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, National Research Council, 2011.

Gross Description:

The mucosa of

the rectum and distal 20 cm of the colon was diffusely hemorrhagic. The liver

was enlarged (~1.5 X), pale tan, and markedly friable. The spleen was also

friable. Other organs were unremarkable.

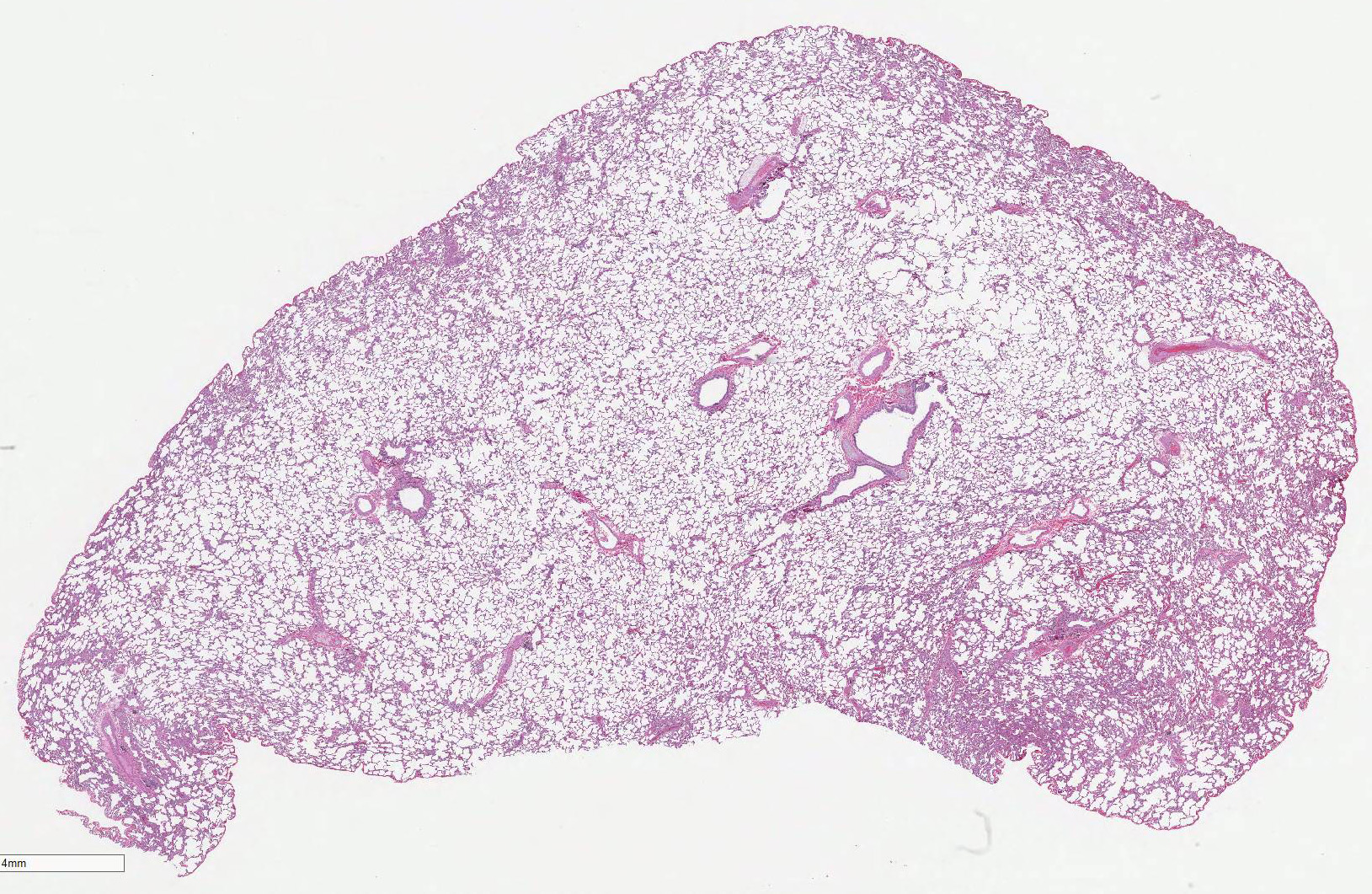

Histopathologic Description:

Lung

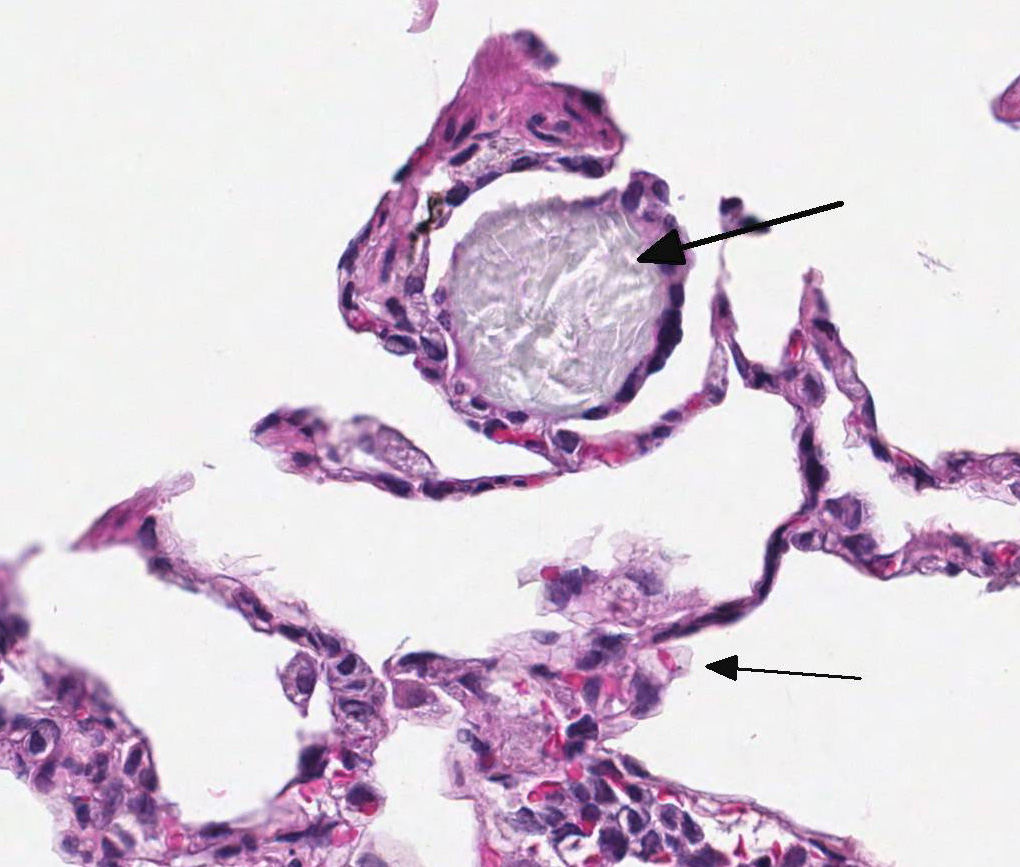

(right inferior lobe): Multifocally within alveoli and often attached to the

alveolar septa, there are low numbers of multinucleated giant cells, measuring

up to 100 µm in diameter, most of which contain intra-cytoplasmic aggregates of

pale blue-gray amorphous to spicular refractile material. The interstitium

also contains scattered aggregates of low numbers of histiocytes containing

intracytoplasmic brown-black finely-granular material. Many blood vessels

contain numerous intraluminal mononuclear leukocytes (monocytes).

Morphologic Diagnosis:

1. Lung;

intravascular leukocytosis (monocytic), moderate

2. Lung; multifocal

histiocytic (multinucleated giant cell) alveolitis, mild, with intracytoplasmic

crystalline foreign bodies

3. Lung; multifocal

interstitial anthracosilicosis, minimal

Lab Results:

None

Condition:

Histiocytic alveolitis with intracytoplasmic crystalline protein

Contributor Comment:

The

timing of this monkeys death is within the usual interval (i.e. 7-11 days)

that cynomolgus macaques die after experimental exposure to a lethal dose of

MARV. There were histologic lesions in the liver, spleen, adrenal glands,

tonsils, and lymph nodes of this monkey that were caused by MARV infection;

these organs are considered target organs for the virus.

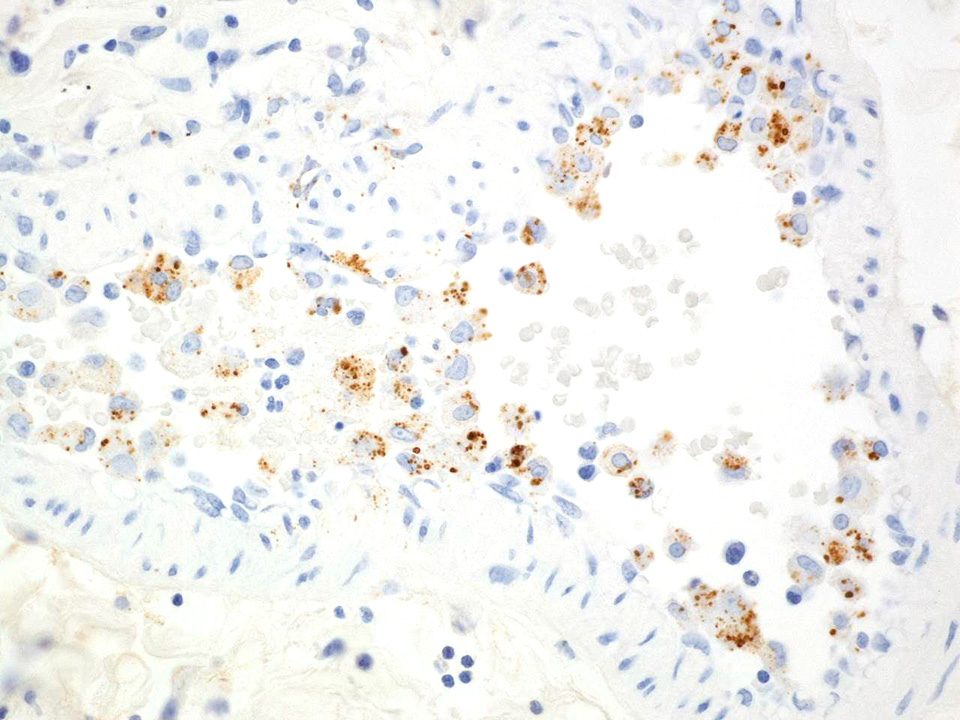

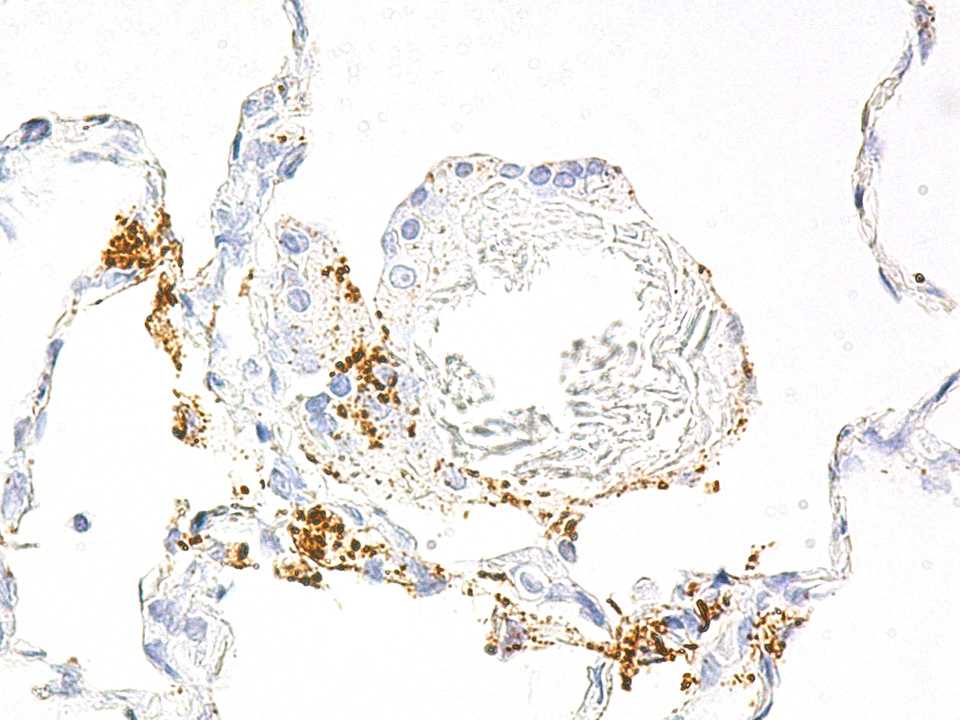

7 Immuno-histochemistry

(IHC) revealed MARV antigen in every organ examined from this animal. The

histologic findings and IHC results confirmed that this macaque died from a

disseminated MARV infection. Although the exact cause of the intestinal bleeding

noted at necropsy was not determined, this was most likely associated with

MARV-induced coagulopathy; disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC) occurs

commonly in primates (including humans) infected with viruses in the

family

Filoviridae (i.e. ebolaviruses and MARV).

6,7

The monocytic

leukocytosis noted within pulmonary blood vessels of this monkey is

attributable to the viral infection. IHC revealed abundant MARV antigen in

many of these monocytes. Cells of the monocyte-macrophage system are infected

very early during the course of filovirus infection and are primarily

responsible for disseminating the viruses throughout the body.

5,7

The presence of

multinucleated giant cells within alveoli and/or attached to alveolar septa of

this monkey was an unexpected finding and was unrelated to the MARV infection.

This lesion was seen in the right inferior lung lobe but not in the other lung

lobes that were examined histologically. These giant cells were an inflammatory

response to the presence of intra-alveolar crystalline foreign material; the

foreign material was initially phagocytized by macrophages that then fused to

form large multinucleated cells.

1 IHC revealed that some of

the giant cells also contained intracytoplasmic MARV antigen.

The composition

of the crystalline foreign material, which is anisotropic in polarized light,

is unknown. However, a review of the medical records for this monkey revealed

that approximately one month before the initiation of the MARV study, this

animal had been administered an oral suspension of Pepcid® once a day for three

consecutive days. It is possible that some of the suspension was aspirated into

the right inferior lung lobe (which is a dependent lung lobe in a primate).

The active ingredient in the Pepcid® suspension is famotidine,

which is a crystalline compound, and inactive ingredients include

microcrystalline cellulose.

2 Overall, the foreign-body alveolitis

was a very mild and clinically insignificant lesion that did not affect the

pathogenesis or outcome of the MARV challenge. Anthracosilicosis is a common

finding in adult macaques and is usually

an incidental lesion (as in this case).

Note: Opinions,

interpretations, conclusions, and recommendations are those of the author and

are not necessarily endorsed by the U.S. Army.

JPC Diagnosis:

Lung: Alveolitis, histiocytic, multifocal, mild with low numbers

of multinucleated giant cell macrophages and abundant intracytoplasmic

crystalline protein, cynomolgus macaque,

Macaca fascicularis.

Conference Comment:

This

interesting case was submitted by the conference moderator and presented

participants with a diagnostic challenge to identify the origin of the

amphophilic, anisotropic, and crystalline material within macrophages and multi-nucleated

giant cells in this section of lung. Most favored the diagnosis of pneumo-coniosis,

which is a lung disease secondary to inhalation of inorganic particulate material,

such as asbestos or silica.

4 Readers are encouraged to review

Wednesday Slide Conference 2015 Conference

3 Case 4 for a review and fascinating discussion of silicate

pneumoconiosis in a horse from California. Silica dusts typically generate a

granulo-matous inflammatory response with fibrosis, not seen in this case.

Additionally, asbestos fibers in the lung are linear and beaded with globoid

ends, also not a feature of this case.

4

There have been sporadic

reports of kaolin aspiration in nonhuman primates causing similar lesions to

this case.

3,8,9 Kaolin is a common crystalline compound found in

antidiarrheal medication as well as a variety of other products, such as

toothpaste, ceramics, soap, and paint. Initially, the terminal bronchioles and

alveoli of animals exposed to aspirated or inhaled kaolin are acutely inflamed,

but by day seven post exposure, there is only mild mononuclear inflammation,

type II pneumocyte hyper-plasia, and aggregates of anisotropic dust-laden

macrophages and multinucleated cells.

9 This is in contrast to silica

inhalation, which induces a progressive granulomatous and fibrotic response.

4,9

The route of exposure of most reported cases in nonhuman primates is aspiration

of oral antidiarrheal medication.

8 Kaolin can also cause granulomas

containing numerous macrophages filled with birefringent crystals if delivered

subcutaneously.

3

To this authors knowledge,

there have been no reported cases of famotidine aspiration causing aspiration

alveolitis in humans or animals; although the pathogenesis posited by the

contributor is plausible. Unfortunately, given strict regulations on tissue

handling of Marburg (MARV)-infected animals, a tissue block was unable to be

submitted for further chemical analysis. Regardless of the origin of the

crystalline proteinaceous material, conference participants agreed that this

lesion is likely unrelated to MARV infection and is an incidental finding.

References:

1. Ackermann

MR. Inflammation and healing. In: Zachary JF and McGavin MD, ed.

Pathologic

Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5

th ed.

St Louis, Mo:

Elsevier, 2012:89-146.

2. Anonymous.

Pepcid oral suspension. Retrieved from: http://www.drugs.com/pro/pepcid-oral-suspension.html.

3. Baskin

GB.

Pathology of nonhuman primates. 1993. New Orleans: Tulane Regional

Primate Research Center.

4. Caswell JL, Willims KJ. Respiratory system. In: Maxie MG ed.

Jubb,

Kennedy, and Palmers pathology of domestic animals. Vol 2. 6

th

ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier; 2016:518.

5. Geisbert

TW, Hensley LE, Larsen T, et al. Pathogenesis of ebola hemorrhagic fever in

cynomologus macaques. Evidence that dendritic cells are early and sustained

targets of infection.

Am J Path. 2003; 163(6):2347-2370.

6. Geisbert

TW, Young HA, Jahrling PB, et al. Pathogenesis of ebola hemorrhagic fever in

primate models. Evidence that hemorrhage is not a direct effect of

virus-induced cytolysis of endothelial cells.

Am J Path. 2003; 163(6):

2371-2382.

7. Hensley

LE, Alves DA, Geisbert JB, et al. Pathogenesis of Marburg hemorrhagic fever in

cynomolgus macaques.

J Inf Dis. 2011; 204 (Suppl 3): S1021-S1031.

8. Herman

SJ, Olscamp GC, Weisbrod GL. Pulmonary kaolin granulomas.

J Can Assoc Radiol.

1982; 33(4):279-280.

9. Vallyathan

V, Schwegler D, et al. Comparative in vitro cytotoxicity and relative

pathogenicity of mineral dusts.

Ann Occup Hyg. 1988; 32:279-289