Signalment:

Gross Description:

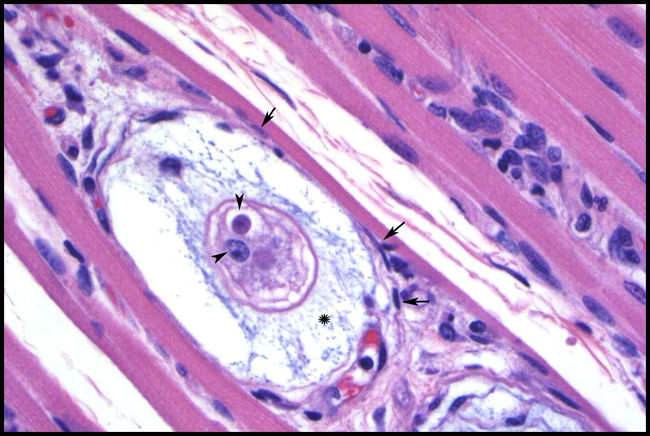

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

It is believed that H. americanum crossed into canids from unknown vertebrates only recently, whereas H. canis has a long history with dogs. The vector for H. americanum is Amblyomma maculatum, gamonts are found in monocytes, and merogony occurs in host cells lodged between striated muscle fibers. In contrast, Rhipicephalus sanguineus is a primary vector for H. canis, the neutrophil is the favored host cell, and merogony takes place in a wide variety of tissues. Meronts of H. americanum develop most consistently in striated muscle within onion skin cysts created by layers of host secreted mucopolysaccharide. No similar lesion is associated with H. canis, which rarely occurs in muscle. Disease from H. americanum is more severe than that seen with H. canis. Developing organisms are shielded from the dogs immune system, but elicit intense local pyogranulomatous inflammation, systemic reaction, and overt illness when merozoites are released. Local lesions evolve into vascular granulomas. Diseased dogs are often febrile and lethargic, with stiff gaits, mucopurulent ocular discharge, and atrophy of the head muscles. Clinicopathological findings include mature neutrophilia, increased alkaline phosphatase, and hypoalbuminemia. Periosteal bone proliferation may be seen radiographically and at necropsy2,3,5.Â

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

When H. americanum was first identified, Rhipicephalus sanguineus was thought to be the vector for transmission, as it is a known vector for H. canis. Even current literature has implied the role of R. sanguineus in transmission of H. americanum.6 In fact, the primary vector for H. americanum appears to be Amblyomma maculatum, as R. sanguineus, Dermacentor variabilis, and Amblyomma americanum appear refractory to infection.3,8

In addition to the lesions within skeletal and cardiac muscle, H. americanum is known to cause severe periosteal bone proliferation of proximal limbs.3 Flat bones can be markedly, but less commonly, affected, and distal limbs are often spared.3 The periosteal reaction shares common features with hypertrophic osteopathy in dogs.3 The pathogenesis of the reaction is unknown, as there are no parasites identified with the bone lesions, and the inciting factors have not been identified.Â

Severe muscle wasting, especially of the temporal muscles, is also a feature of H. americanum.3

We thank Dr. C. H. Gardiner, PhD, veterinary parasitology consultant to the AFIP, for his review of this case.

References:

2. Baneth G, Mathew JS, Shkap V, MacIntire DK, Barta JR, and Ewing SA: Canine hepatozoonosis: two disease syndromes caused by separate Hepatozoon spp. Trends in Parasitology 19:27-31, 2003.

3. Ewing SA and Panciera RJ: American canine hepatozoonosis. Clin Microbiol Rev 16:688-697, 2003.

4. Gardiner CH, Fayer R, Dubey JP: An Atlas of Protozoan Parasites in Animal Tissues, 2nd ed., p. 4. Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, DC, 1998

5. Panciera RJ, Mathew JS, Cummings CA, Duffy JC, Ewing SA, and Kocan AA: Comparison of tissue stages of Hepatozoon americanum in the dog using immunohistochemical and routine histologic methods. Vet Pathol 38:422-426, 2001.

6. Valentine BA, McGavin MD: Skeletal muscle. In: Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease, eds. McGavin MD, Zachary JF, 4th ed., pp. 1035-1037. Elsevier, St. Louis, MO, 2007

7. Van Vleet JF, Valentine BA: Muscle and tendon. In: Jubb, Kennedy, and Palmers Pathology of Domestic Animals, ed. Maxie MG, 5th ed., vol. 1, pp. 270-271. Elsevier Limited, St. Louis, MO, 2007 8. Vincent-Johnson NA, MacIntire DK, Lindsay DS, Lenz SD, Baneth G, Shkap V, and Blagburn BL: A new hepatozoon species from dogs: description of the causative agent of canine hepatozoonosis in North America. Am J Parasitol 83:1165-1172, 1997.Â