Signalment:

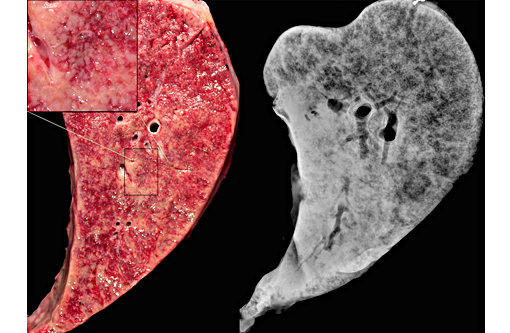

Gross Description:

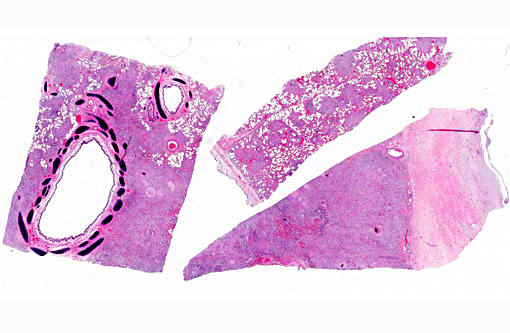

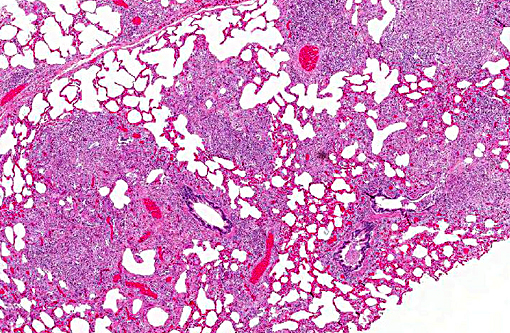

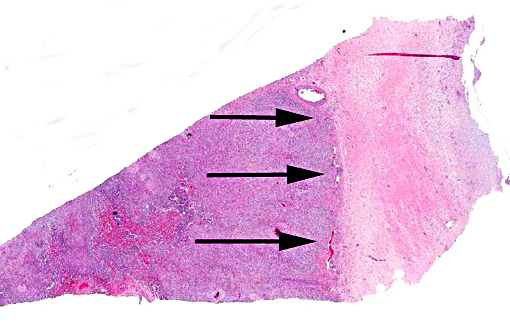

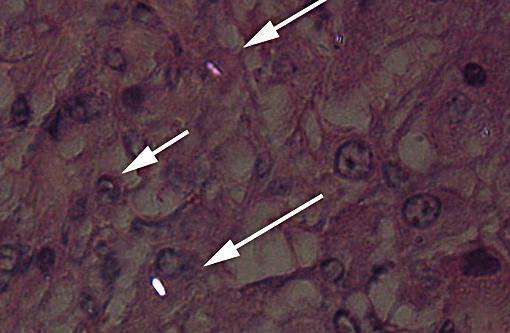

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lung: Severe, generalized, multi-nodular to confluent granulomatous pneumonia with intralesional crystals, parenchymal and pleural fibrosis, necrosis and mineralization

Tracheobronchial, cervical, mediastinal, thoracic aortic lymph nodes (not submitted): Necrotizing and fibrosing granulomatous lymphadenopathy with mineralization and intralesional crystals

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Common presenting signs in horses with silicosis include weight loss, exercise intolerance, respiratory distress, or increased respiratory effort.(2) Typical pulmonary radiographic findings in cases of PS have been described in detail, and are characterized by a diffuse, interstitial pattern ranging in distribution from miliary to micronodular to linear; alveolar consolidation is commonly seen.(2) Gross lesions in uncomplicated cases of PS are usually limited to the pulmonary system. Histologically, lesions are similar to the case presented here with lesions being limited to the pulmonary system and draining lymph nodes. PS is sometimes observed concurrently with bone fragility syndrome. Lesions of the latter have been statistically correlated to pulmonary silicosis; in these cases, the term silica-associated osteoporosis has been proposed (SAO).(3) Gross lesions of SAO reflect systemic osteoporosis and are most apparent in the axial skeleton, particularly the scapulae, ribs, spine and pelvis. For example, bowing of the scapulae and irregular thickening of the scapular spine is one of the prominent features of advanced SAO. Multiple pathological fractures in the ribs and regional expansion of the cortex with porous bone in the axial skeleton are common post mortem findings. Pathological fractures of the scapulae, pelvis and vertebrae are common as well.(1) Osteolytic foci and loss of cortical bone definition are variably observed radiographically in the bones of the axial skeleton and proximal portion of the appendicular skeleton.(1) Increased, heterogeneous radiopharmaceutical uptake associated with increased bone turnover are commonly found in cervical vertebrae, scapulae, ribs, sternebrae and pelvis (Optional JD. Anderson et al 2008). The histological feature of SAO are numerous, large osteoclasts with supernumerary nuclei and foamy cytoplasm that excessively resorb trabecular and cortical bone within osteolytic lesions.(1) Large cavities and thin disordered trabeculae commonly replace parent cortical and trabecular bone. Additionally, disordered osteonal formation results in a mosaic pattern of lamellar bone packets.(1) The etiopathogenesis of SAO is unknown.(1)

In this case, definitive silicosis-associated skeletal lesions were not identified. Although the mare had a healing fracture callus in the pelvis, which is commonly seen in cases of SAO, typical osteoporotic lesions were not observed grossly or radiographically. This case represents an uncomplicated case of PS without confirmed SAO.

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

This case was additionally studied in consultation with the Department of Pulmonary and Mediastinal Pathology, whose pathologists have more familiarity and experience with the pathology of pulmonary silicosis, a common occupational exposure in humans. Similar to the contributor and conference participants, the pathologists described the lesions in this case as being centered on small airways (bronchiolocentric), an observation more apparent in the less affected areas of the lung. Specific changes they described include airway constriction, distortion, obliteration and metaplasia secondary to granulomatous inflammation; the bronchiolocentric nature of the lesions indicates the airway as the route of injury. They interpreted the pattern of the granulomatous inflammation as more commonly associated with an infectious etiology versus pulmonary silicosis, such as that from a fungal or mycobacterial agent; in humans, the inflammatory pattern can also occur with inhaled antigens. In their evaluation, the histologic changes in this horse would be atypical for pulmonary silicosis, as the condition in humans typically consists of well-circumscribed nodules with a central area of lamellated collagen bundles surrounded by a thick rim of histiocytes. Furthermore, the nodules seen in human cases of pulmonary silicosis most often contain many more birefringent crystals compared with the extremely low number seen in this individual. Various tissue histochemical stains of submitted unstained serial sections did not demonstrate microbial organisms in this horse.

In addition to pulmonary silicosis, conference participants also included equine herpes virus 5 (equine multinodular pulmonary fibrosis) and mycobacterial infection in the differential diagnosis. Equine multinodular pulmonary fibrosis is histologically characterized by marked interstitial fibrosis with alveolar like architecture lined by cuboidal epithelial cells. Macrophages and neutrophils are present in airways in variable numbers, and intranuclear inclusion bodies are occasionally seen in macrophages.(7) Mycobacterial agents known to cause granulomatous pneumonia in horses include Mycobacterium avium complex, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium bovis. Unlike ruminants, the granulomas in horses typically do not have prominent casseous necrosis or calcification in the center of lesions, and extensive fibrosis is seen with chronicity, giving the lesions a sarcomatous appearance.(4)

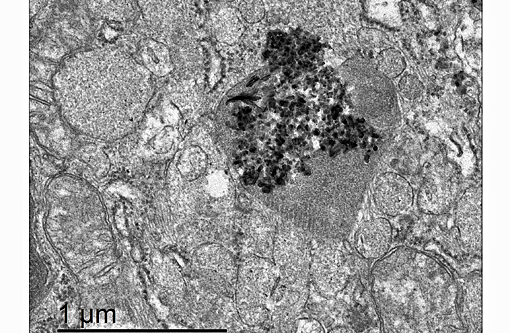

We thank the contributor for providing excellent supporting materials with the case submission, which immensely increased the teaching and learning value of this very interesting case, including the superb gross and electron microscopy images, radiographs and clinical pathology data.

References:

1. Arens AM, Barr B, Puchalski SM, et al. Osteoporosis associated with pulmonary silicosis in an equine bone fragility syndrome. Vet Pathol. 2011;48:593-615.

2. Berry CF, OBrien TR, Madigan J, Hager DA. Thoracic radiographic features of silicosis in 19 horses. J Vet Intern Med. 1991;5:248-256.

3. Durham MG, Armstrong CM. Fractures and bone deformities in 18 horses with silicosis. AAEP Proc. 2006;52:1-7.

4. L³pez A. Respiratory system, mediastinum and pleurae. In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2012:501-509.

5. Myers RK, McGavin MD, Zachary JF. Cellular adaptations, injury, and death: Morphologic, biochemical and genetic bases. In: McGavin MD, Zachary JF, eds. Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 5th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier; 2012:39-43.

6. Schwartz LW, Knight HD, Whittig LD, Malloy RL, Abraham JL, Tyler NK. Silicate pneumoconiosis and pulmonary fibrosis in horses from the Monterey-Carmel peninsula. Chest. 1981;80:82-85.

7. Williams KJ. Gammaherpesviruses and pulmonary fibrosis: Evidence from humans, horses and rodents. Vet Pathol. 2014;51(2):372-384.