Wednesday Slide Conference, 2025-2026, Conference 12, Case 4

Signalment:

2-years-old, female, rabbit, Oryctolagus cuniculus domesticusHistory:

Gross Pathology: The midbody of the right uterine horn had a circular lump (0.6 cm in diameter). The cut section of this lump appeared white and solid.Laboratory Results:

N/AMicroscopic Description:

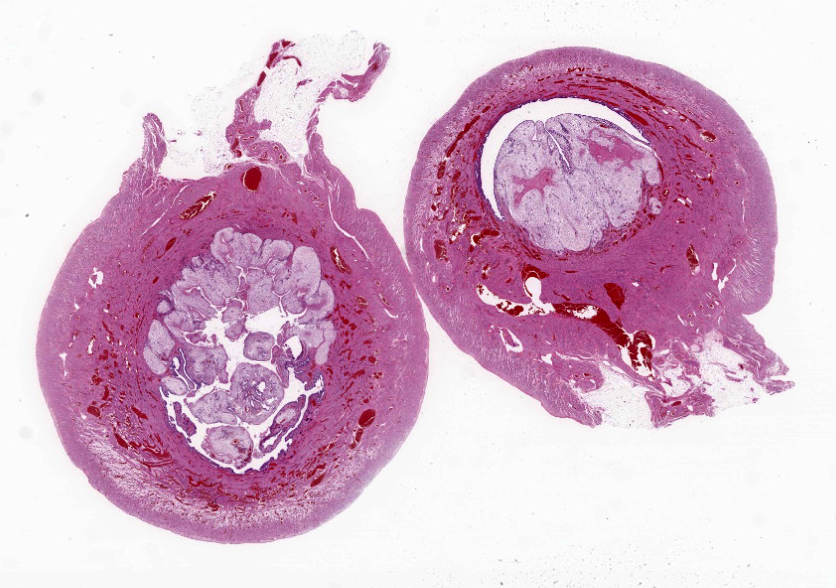

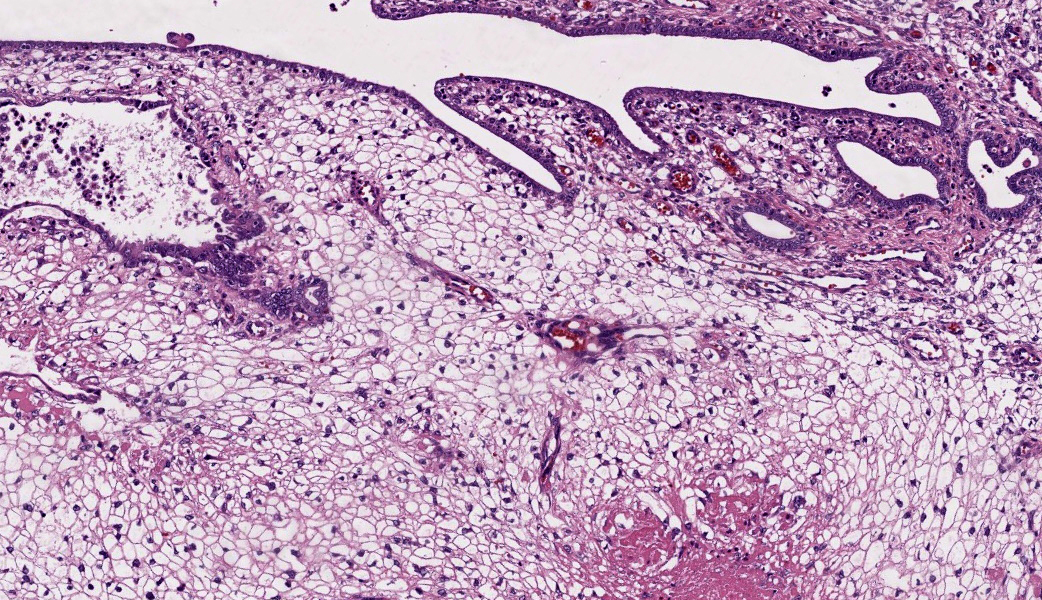

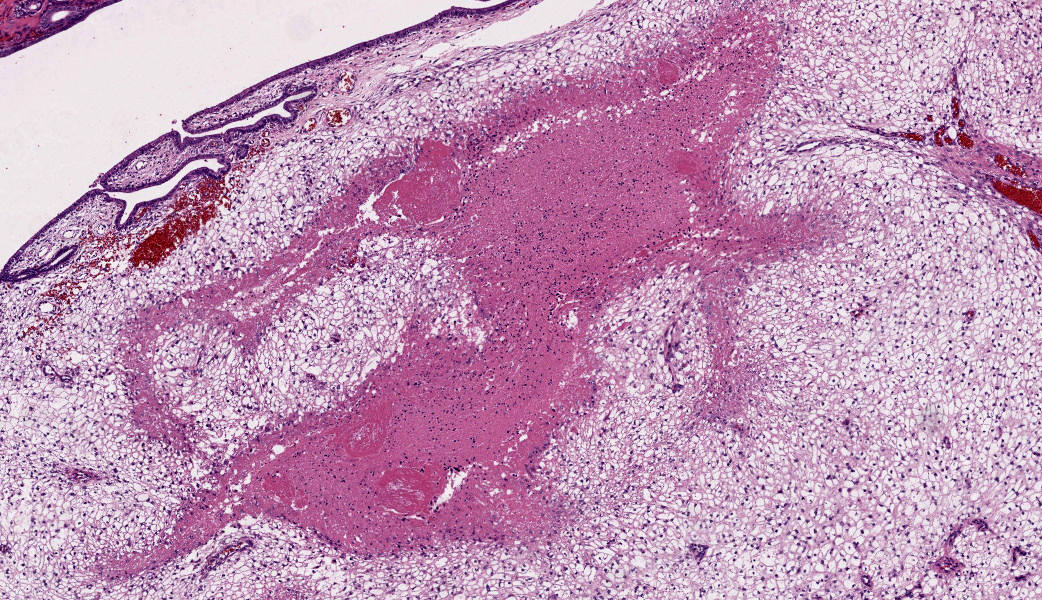

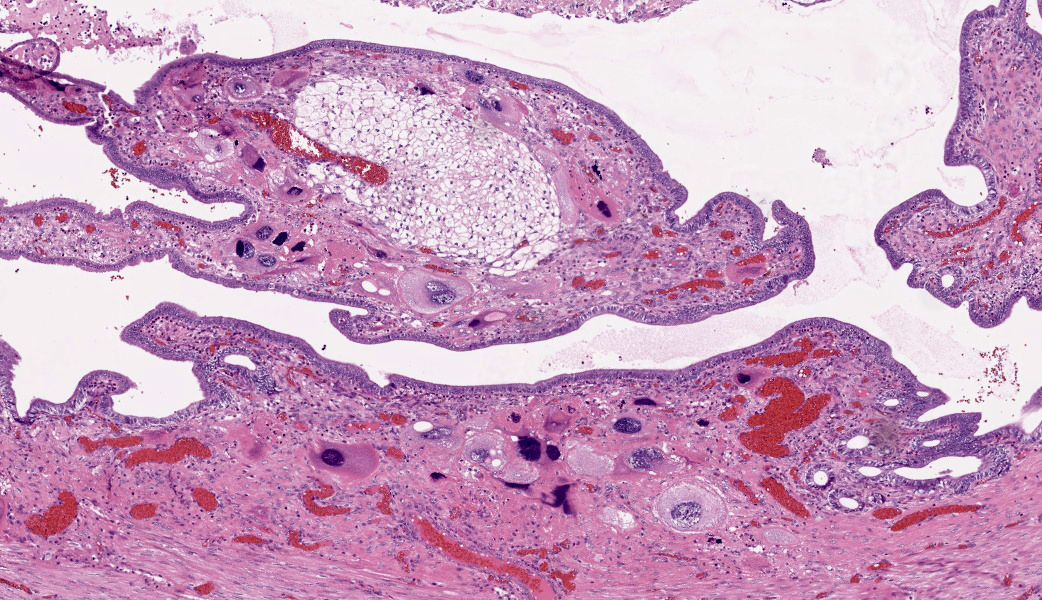

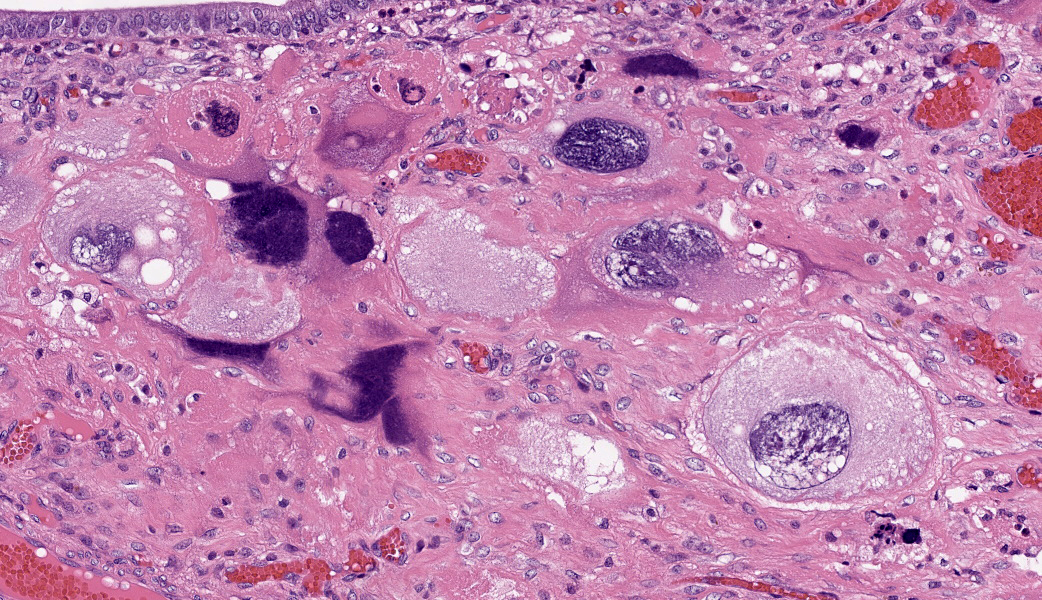

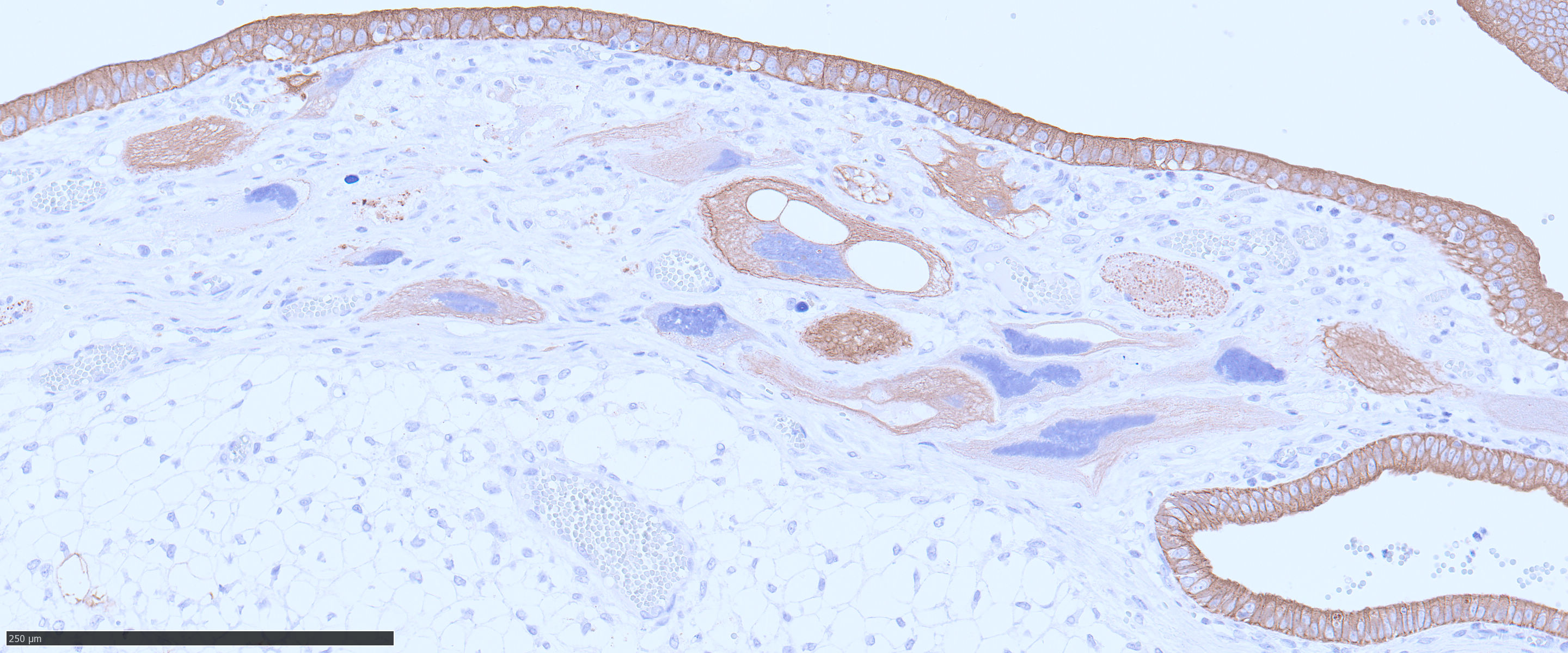

The endometrium on the mesometrial side of the uterus proliferated with the formation of large nodules and numerous polyps. The surface of the nodules and polyps was covered by endometrial epithelium, however, approximately 50% of the epithelium were eroded. The polyps and nodule contained numerous blood vessels with normal endothelium, along with cells that resembled large-vacuolated decidual cells, arranged in sheets. The decidual cells had distinct cell boundaries, a round shape, abundant transparent cytoplasm, and nuclei ranging from oval to irregular shapes. Mitotic figures were also occasionally observed. Just beneath the endometrial epithelium, the decidual cells exhibited a spindle-shaped morphology. (Fig.1 and 2)On the antimesometrial side of the uterine, endometrial hyperplasia was mild, decidual cells in the endometrial stroma were sparse, and proliferation of huge giant cells resembling trophoblast was prominent. The huge giant cells displayed a variety of morphologies, including round, spindle, to pleomorphic, with notably large, highly atypical nuclei and abundant cytoplasm. Multinucleated giant cells were also observed.The immunohistochemical analysis demonstrated that normal endometrial epithelium is positive for progesterone receptor (PgR), keratin AE1/AE3, and CAM5.2, and negative for CD10, SMA and desmin. Normal endometrial stromal cell is positive for PgR and CD10, and negative for keratin AE1/AE3, CAM5.2, SMA and desmin. Decidual cell is positive for PgR and CD10, and negative for keratin AE1/AE3, CAM5.2, SMA and desmin. The huge giant cells exhibited positive for keratin AE1/AE3, CAM5.2 and CD10, and negative staining for PgR, SMA and desmin.

Contributor's Morphologic Diagnoses:

Uterus: Decidual reactionContributor's Comment:

Rabbits have a hemodichorial and bidiscoid type of placenta. Histologically, the placenta of rabbits is composed of the labyrinth zone, the junctional zone, the decidua zone, and the mesometrium.3,6,7 In the labyrinth zone, there are two layers of trophoblasts, an outer and inner layer separating the maternal blood spaces from the fetal blood vessels. The outer trophectoderm is comprised of the syncytiotrophoblasts. The inner trophectoderm is one layer of cytotrophoblasts overlying fetal blood vessels. The junctional zone is composed of glycogen cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm containing PAS-positive substances and giant cells having often 2-3 number of nuclei. The decidua originates from stromal cells of the mesometrial endometrium. Before 11 days of pregnancy, it consists of proliferating spindle cells, subsequently, vacuolated cells known as decidual cells begin to appear. The proliferation of decidual cells continues, and from 13 days of pregnancy, necrosis of decidual cells begins to be observed. In mid-gestation, the decidual zone is divided into the zone of necrosis and the zone of separation. 3,6,7 The zone of necrosis develops with dilated blood vessels as pregnancy advances. This zone is detected under the junctional zone and is composed of necrotic tissue. The zone of separation, which is composed of the cells having large foamy cytoplasm, becomes thinner without necrosis as pregnancy advances. 3,6,7During pregnancy in rabbits, a characteristic feature is the presence of giant cells on the obplacental (antimesometrial) region. These giant cells are referred to as obplacental giant cells to distinguish them from certain cell populations of the definitive (chorioallantoic) placenta and decidua. 1 Immunocytochemistry shows that the giant cells are positive for cytokeratin and vimentin, but are negative for desmin and Factor VIII-related antigen. The cells are positive for cytokeratin from their inception, but only become vimentin-positive between Days 12 and 15 of pregnancy, a change seemingly related to their detachment from epithelial tissue to take on an independent existence.

The case was characterized by the proliferation of vacuolated cells in the endometrial stroma covered by normal endometrial epithelium.?In the presence of an embryo and normal placental formation, trophoblasts attached to the outer surface of the endometrial epithelial cells.3,6,7 However, in this case, the absence of trophoblast cell proliferation clearly indicates that normal placental formation has not occurred. It can thus be concluded that only vacuolated cells of maternal origin are proliferating. The vacuolated cells exhibited a morphology similar to that of decidual cells during normal placental formation and frequently contained PAS-positive granules, further supporting this interpretation. Immunohistochemical staining revealed positivity for CD10, negativity for keratin and positivity for progesterone receptors. These findings are consistent with the staining pattern of endometrial stromal cells and provide further confirmation of the origin of these cells from the endometrial stroma. Sensitization by progesterone is necessary for the initiation of decidualization of the endometrial stroma, and stable progesterone activity is necessary for the stable existence of decidual cells.2 In this case, the expression of progesterone in both the endometrial stroma and epithelium indicates that a decidual reaction has occurred overall.

In contrast, numerous giant cells were observed on the obplacental (antimesometrial) region. These giant cells are similar to obplacental giant cells formed in the pregnant uterus of rabbits with regard to both cell morphology and location. 1 The origin of these cells remains unclear. The absence of obvious trophoblasts and the formation of giant cells in the endometrial stroma beneath the normal endometrial epithelium suggest a uterine origin. However, immunostaining revealed positivity for CK and CAM5.2 (epithelial marker) and CD10 (positive for endometrial stromal cell), and negative for PgR (positive for both endometrial epithelial and stromal cell), which did not correspond with the staining patterns of endometrial epithelial or stromal cells. Consequently, it was not possible to ascertain their origin with any degree of certainty.

The decidual reaction is a well-documented phenomenon in rats, which can be categorized into two distinct types. The first type is characterized by the formation of nodules in the uterine cavity, exhibiting a high degree of structural organization and regional variation. The second type is referred to as focal decidualization, which is marked by the proliferation of decidual cells within a specific area of the endometrial stroma. Decidual cells in rats are large cells with oval nuclei and eosinophilic cytoplasm, characterized by PAS-positive small vacuolated cytoplasm. In the present case, although the lesions in rabbits corresponded to the focal decidualization observed in rats due to the absence of clear organization, the morphology of decidual cells differed, with rabbits exhibiting distinct vacuolated cells. The substantial disparities in placental formation among different animal species imply that the morphology of decidual reactions also exhibits considerable variation.

Contributing Institution:

Setusunan Univeristy, Laboratory of Pathology, Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences 45-1 Nagaotoge-cho, Hirakata, Osaka JAPAN 5730101JPC Diagnoses:

Uterus, endometrial stroma: Decidual reaction, subacute, focally extensive, severe, with trophoblastic giant cells.JPC Comment:

This final case provided a not-oft seen entity in diagnostic pathology, but one that is frequently encountered in research animals. Many thanks to the contributor for providing this highly educational case, along with an excellent write-up on rabbit placentation and decidual reactions. Being able to identify a decidual reaction as such and not mistaking it for another lesion is an important part of understanding the normal reproductive physiology of species with a deciduate uterus. The degree of proliferation in this case caused some participants to pause a suggest possible diagnoses such as deciduoma vs focal decidualization, but the ultimate consensus following consultation with reproductive specialists was that this is consistent with the spectrum of decidual reaction in a rabbit. MAJ Travis used this case as an opportunity to review pertinent reproductive physiology, which encompassed much of this case’s discussion and will be summarized here.Ovarian follicle development starts with primordial follicles, which are surrounded by a single layer of squamous epithelial follicular cells. Primordial follicles then develop into primary follicles that are encircled by a single layer of plump cuboidal follicle cells.10 In primary follicles, the zona pellucida, a thick, glycoprotein-rich layer, forms between the primary oocyte and the adjacent follicle cells. In the later developmental stages of the primary follicle, the follicular cells surrounding it undergo stratification into the stratum granulosum/membrana granulosa, which is avascular.10 At this point, the follicle cells are now known as granulosa cells. Simultaneously, the stromal cells surrounding the late primary follicle form a sheath of connective tissue, known as the theca folliculi, that differentiates into the theca interna, which is an inner, highly vascularized layer containing cuboidal secretory cells, and the theca externa, composed of an outer layer of smooth muscle and collagen. The cells of the theca interna have many luteinizing hormone (LH) receptors and synthesize an androgen precursor to estrogen. However, without the help of granulosa cells, thecal calls cannot convert this androgen precursor into estrogen. The granulosa cells, under the influence of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) from the anterior pituitary gland, catalyze the conversion of the precursor to estrogen, which enables further proliferation of granulosa cells.

Primary follicles develop into secondary (also called antral) follicles, which are characterized by a proliferation of granulosa cells that increase the follicle’s size in the presence of sufficient FSH, growth factors, and calcium. Fluid-filled cavities appear among the granulosa cells and coalesce to form a single, crescent-shaped cavity (the antrum).10 As this antrum enlarges, its lining of granulosa cells forms a thickened layer around the primary oocyte. This layer is called the “cumulus oophorous.” These cells immediately surrounding the oocyte remain after ovulation and become known as the corona radiata.8

Finally, the mature/graafian follicle, housing a mature secondary oocyte, causes a bulge on the ovarian surface. Increased pressure in the antrum leads to attenuation of the granulosa cells and the development of the single layer of corona radiata cells around the secondary oocyte.10 Approximately 24hrs prior to ovulation, the anterior pituitary releases a surge of FSH and LH in response to the rise in estrogen production from the follicle. Following this surge, LH receptors on the granulosa cells are downregulated and no longer produce estrogens, resulting in a decrease in estrogen that enables a subsequent rise in progesterone. During ovulation, the secondary oocyte is released from the mature follicle. Increased antral pressure effectively causes the oocyte, with its corona radiata, to explode out of the follicle. The peristaltic action of the theca externa’s smooth muscle layer enables the freed oocyte to be propelled towards the fimbria of the oviduct. From there, the oocyte adheres to the fimbriae and is then actively transported into the uterus by ciliated cells that line the uterine tube.

Following the rather traumatic exit of the oocyte from the follicle during ovulation, the ruptured follicle experiences bleeding from the capillaries of the theca interna into the follicular lumen, earning it the name “corpus hemorrhagicum” (CH). The remaining follicular wall, composed of granulosa and thecal cells, is thrown into deep folds as the follicle collapses. The granulosa cells and the theca interna then differentiate into granulosa luteal and theca luteal cells through a process known as “luteinization” to form the “corpus luteum” (CL). Granulosa luteal cells are large and compose roughly 80% of the CL. They synthesize estrogen, progesterone, and inhibin (inhibin regulates production of FSH). By contrast, theca luteal cells are small and make up the remaining ~20% of the CL. They secrete androgens and progesterone. As the CL begins to form, blood vessels rapidly grow in to form a rich and complex vascular network. Progesterone and estrogen produced by the CL stimulate the growth and secretory activity of the endometrium to prepare for implantation of a fertilized oocyte. In cases where fertilization occurs, chorionic gonadotropin (CG) is produced by the early placenta, which stimulates consistent progesterone secretion from the CL to maintain the pregnancy. If no fertilization occurs, there is no CG production and the CL degenerates, leaving a scar known as the “corpus albicans” (CA). Over time, the CA shrinks and fades away.10

Once ovulation has occurred, an oocyte has roughly 24hrs to be fertilized.8 Sperm cells, upon contact with an oocyte, penetrate the oocyte by binding to zona pellucida receptors and releasing enzymes to degrade the corona radiata. Once a spermatozoon gains entry to the oocyte, the nucleus of the sperm’s head is incorporated into the oocyte, where it will release its DNA and start the formation of the zygote. The fertilized oocyte then undergoes a series of changes while passing through the uterus, dividing many times to form a ball of cells called a morula (Latin for “mulberry”), which is still surrounded by a zona pellucida. Through subsequent cell divisions, the embryo loses its zona pellucida and forms a hollow sphere (blastocyst) with a centrally located cluster of cells called the “embryoblast”, which will develop the amniotic sac, fetal yolk sac, and fetus. The embryoblast is surrounded by a layer of cells that will form trophoblasts, which ultimately become the placenta.

Trophoblasts, when they contact the uterine wall, begin to proliferate and invade the endometrium. Trophoblasts are biphasic and include cytotrophoblasts, which form the mitotically active inner cell layer, and syncytiotrophoblasts (which are a further differentiation of cytotrophoblasts) that form the outer layer, are not mitotically active, are frequently multinucleated, and actively invade the epithelium and underlying uterine stroma to facilitate implantation of the embryo.8 Syncytiotrophoblasts secrete chorionic gonadotropin to support the CL and maintain the pregnancy in a sort of, “I’m still here and active, don’t let me die,” feedback loop.

Animals with a deciduate (meaning “falling off/shedding”) uterus have a portion of the endometrium, primarily the antimesometrial portion, that undergoes morphologic changes that can be seen histologically. The maternal portion of the endometrium that undergoes these changes and ultimately tears away with the placenta is called the “decidua”.8 The decidua provides physical support, nutrition, immunological protection, and hormonal support to the developing embryo.8 Species with a deciduate uterus include rabbits, humans, rodents, and non-human primates, and the histologic appearance of the decidual reaction varies between species.3,7 Animals with a deciduate uterus shed their placenta at parturition and it includes all but the deepest layer of the endometrium. The process of decidualization involves stromal cells, also called “decidual cells”, that become large and rounded in response to increased progesterone. There are three regions of the decidua named based on their relationship to the site of embryo implantation and include the decidua basalis (endometrium that underlies implantation site), the decidua capsularis (thin portion of the endometrium between the implantation site and the uterine lumen), and the decidua parietalis (the remaining endometrium of the uterus).

In the absence of pregnancy, a decidual reaction is thought to be a proliferative response of stromal endometrial cells that is histologically similar to decidual implantation sites. It is associated with pseudopregnancy and nonspecific physical stimuli. It requires both estrogen and progesterone to be present, and there must be some form of physical stimulus to induce the reaction.2 In research, this can be done by scratching the endometrium and then supporting with estrogen and progesterone administration. In toxicological studies, the presence or absence of a decidual reaction is considered a sensitive indicator of estrogenic or anti-estrogenic activity.3,4,10

References:

- Blackburn DG, Osteen KG, Winfrey VP, Hoffman LH. Obplacental giant cells of the domestic rabbit: development, morphology, and intermediate filament composition. J Morphol. 1989;202:185-203.

- Fischer B, Chavatte-Palmer P, Viebahn C, Navarrete Santos A, Duranthon V. Rabbit as a reproductive model for human health. Reproduction. 2012;144(1):1-10.

- Furukawa K, Kuroda Y, Sugiyama A. A comparison of the histological structure of the placenta in experimental animals. J Toxicol Pathol. 2014;27:11-18.

- Furukawa K, Tsuji N, Sugiyama A. Morphology and physiology of rat placenta for toxicological evaluation. J Toxicol Pathol. 2019;32:1-17.

- Gnecco JS, Ding T, Smith C, Lu J, Bruner-Tran KL, Osteen KG. Hemodynamic forces enhance decidualization via endothelial-derived prostaglandin E2 and prostacyclin in a microfluidic model of the human endometrium. Hum Reprod. 2019;34(4):702-714.

- Greaves P. Female genital tract. In: Histopathology of Preclinical Toxicity Studies: Interpretation and Relevance in Drug Safety Evaluation, 3rd ed., pp728-729. Elsevier, London, UK, 2007.

- Kotera K. Histological observation of the chronological changes in the constituent zones of the rabbit placenta. Jpn J Anim Reprod. 1986;32: 69–77.

- Schlafer DH, Foster RA. Female Genital System. In: Maxie MG, ed. Jubb, Kennedy & Palmer's Pathology of Domestic Animals. Vol 3. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2016:358-464.

- Yoshizawa K, Emoto Y, Kinoshita Y, Kimura A, Uehara N, et al. Histopathological and immunohistochemical characterization of spontaneously occurring uterine deciduomas in young adult rats. J Toxicl Pathol. 2013;26:61-66.

- Zhang XK, Li X, Han XX, Sun DY, Wang YQ, Cao ZZ, Liu L, Meng ZH, Li GJ, Dong YJ, Li DY, Peng XQ, Zou HJ, Zhang D, Xu XF. Cadmium induces spontaneous abortion by impairing endometrial stromal cell decidualization. Toxicology. 2025;511:154069.