Joint Pathology Center

Veterinary Pathology Services

Wednesday Slide Conference

2018-2019

Conference 19

30 January, 2019

CASE IV: M17-69 (JPC 4102647).

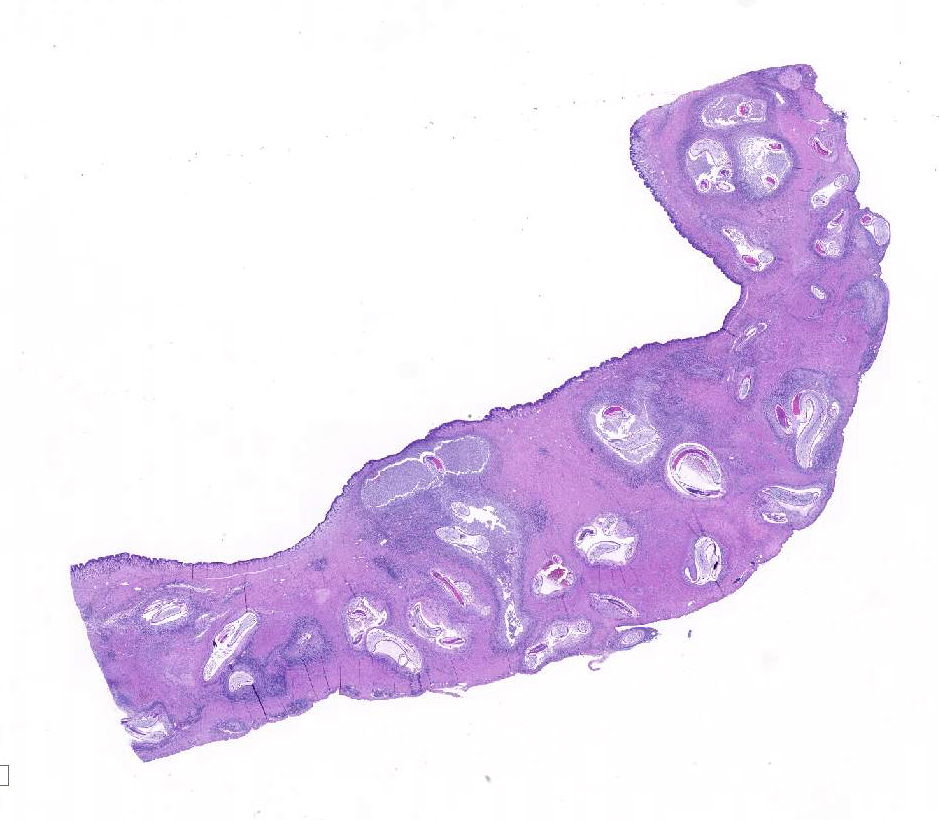

Signalment: Juvenile (age unknown), female, American paddlefish (Polyodon spathula)

History: The fish was found dead in a stable aquarium system.

Gross Pathology: Multiple fixed tissues were received for histopathology as a mail-in necropsy. The fish was reported to be in fair to poor physical condition. Multifocal, widespread, 1-2 mm, white to tan nodules were observed on serosal and cut surfaces of the stomach and pyloric ceca during tissue trimming.

Laboratory results: N/A

Microscopic Description:

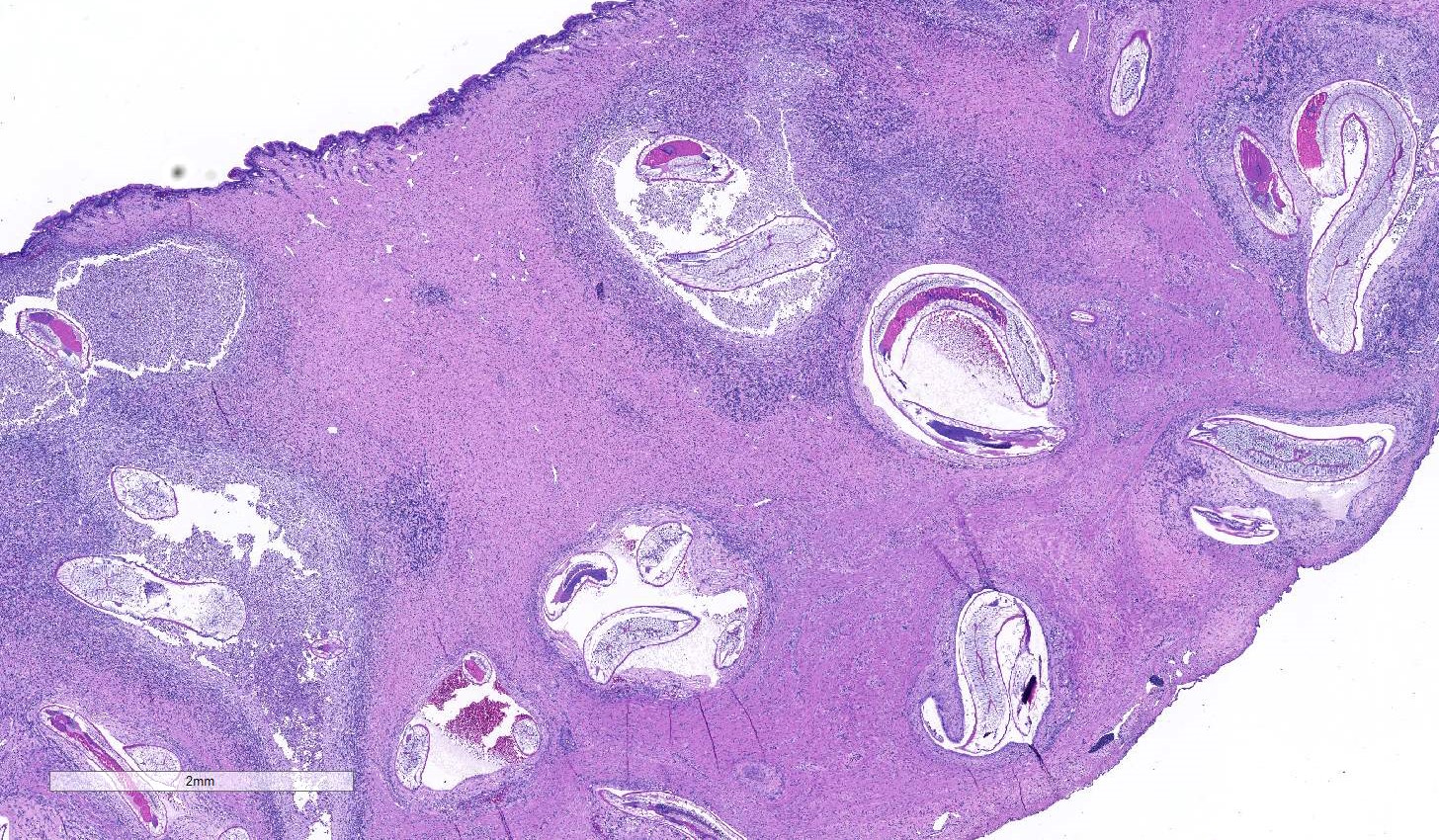

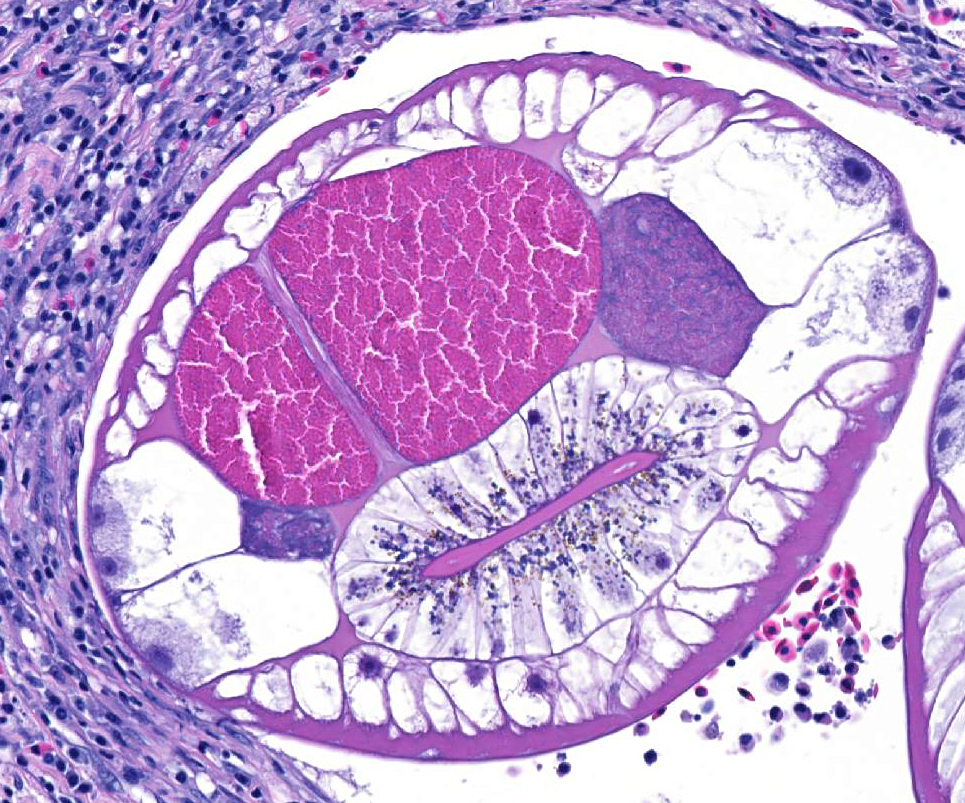

Stomach: The submucosa and muscularis are widely expanded by severe fibrosis and inflammatory infiltrates surrounding large numbers of larval nematodes. Features of the pseudocoelomate parasites include a smooth cuticle, coelomyarian/polymyarian musculature, lateral cords with eosinophilic gland cells, triradiate glandular esophagus, cecum, and large intestine lined by tall uninucleate columnar cells with a brush border. Worms are coiled within cavitated lesions partially filled by loosely associated mixtures of degenerate cells, necrotic cellular debris, erythrocytes and mixed inflammatory cells. More organized, unevenly thick mantles, composed of variable mixtures of eosinophilic granulocytes, macrophages, lymphocytes, plasma cells and fibroblasts gradually dissipate into the adjacent gastric wall. The lamina contains sparse, often short glands, with reduced cytoplasm and cytoplasmic granules, widely separated by abundant dense collagenous tissue.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Stomach: Gastritis, mural, widespread, chronic, severe, with glandular atrophy and loss, and larval nematodes

Contributor’s Comment: The American paddlefish is a large, filter-feeding, cartilaginous, freshwater fish that is closely related to the sturgeons. Paddlefish roe, like that of several sturgeon species, is highly valued as caviar and supports a growing aquaculture industry.4 Microscopic examination revealed severe inflammatory changes and fibrosis, with glandular atrophy and loss in the stomach and cecal walls in association with large numbers of larval nematodes. Features of the worms and the associated histologic changes are compatible with descriptions of the anasakid nematode Hysterothylacium dollfusi, a major parasite of and impediment to the pond-culture of paddlefish.1,5 Although gastric ulceration was not present in the sections evaluated, the severe changes and glandular loss suggest maldigestion and malabsorption, consistent with the poor condition of this fish. Additional findings included severe hepatocellular and pancreatic acinar cell atrophy suggesting prolonged anorexia and catabolism of hepatic lipid stores. The Anisakidae are a family of intestinal nematodes, including the well-known genera Anisakis, Contracaecum and Pseudoterranova. Representative Anisakis spp., most notably A. simplex, and Pseudoterranova spp. have the potential to cause zoonotic infections in humans (anisakidosis) when larvae are ingested in raw or insufficiently cooked fish. Anisakidosis caused by Contracaecum and Hysterothylacium spp. are rare. The life cycles of the genera are complex, involving an invertebrate first intermediate host, fish or cephalopod second intermediate host and often a bird or marine mammal final host.2,3

Contributing Institution:

University of Georgia, College of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Pathology, 501 DW Brooks Drive , Athens, GA 30602, www.vet.uga.edu/VPP

JPC Diagnosis: Stomach, muscularis and serosa: Granulomas, numerous with larval ascarids and mild chronic granulocytic and lymphoplasmacytic gastritis.

JPC Comment: Anisakis sp. and Pseudoterranova sp. the causative agents of anisakidosis in humans, utilize marine fish as paratenic hosts and whales and dolphins and seals and sea lions, respectively, as definitive hosts. Humans, which may develop abdominal pain, diarrhea and nausea (as well as strong allergic reactions) as accidental nonpermissive hosts. The infection of humans by species of Anisakis is called “anasakiasis”, while “anisakidosis” refers to infection by any member of the Anisakidae. 6

Parasitized humans may experience abdominal pain within a few hours to a few days following ingestion of infected raw fish. Infection may occur in the stomach (where worms may be removed by gastroscopy, or the intestine (which often requires surgery and may result in obstruction as a result of severe inflammation (which may expand the intestinal wall 3-5 times. Rare cases of “ectopic anisakiasis” may result from larval penetration within the pharynx, tongue, lung, peritoneal cavity, or pancreas. Another form of anasakidosis is gastroallergic anasikidosis, which may not present with gastrointestinal symptoms, but instead with various degrees of urticarial, angioedema, and anaphylaxis. In fact, the vomiting and diarrhea associated with allergic reactions, may actually expel the larva from the body6. Interestingly, gastric allergic anisakiasis are relatively common in certain countries, including Spain and Italy, has been reported in Japan and Korea, but is rare in other parts of the world – possibly due to awareness of the condition in these parts of the world. It is not clear whether it takes live larvae or antigens from dead larvae to set off a gastroallergic reaction, as patients with previous gastroallergic anisakiasis will not react to exposure to dead larvae or antigens, while fish processing works may develop Anisakis-induced asthma, rhinoconjunctivitis, or dermatitis.6

In humans, larvae that penetrate the gastric wall, but usually die within a few days in humans. The larvae will break down in eight weeks, with eosinophils being a large component of the inflammatory lesion. Dead Anisakis larvae may incite granuloma formation within tissues and may be associated with systemic neutrophilia or eosinophilia.6 The presence of inflammatory nodules may be mistaken for neoplasia, highlighting the importance of taking a good history in cases of acute onset of epigastric pain and intestinal symptoms.

In addition to reviewing anisakiasis in animals, the moderator reviewed additional large zoonotic heminthic disease, to include dracunculiasis and diphyllobothriasisis.

References:

1. Gardiner CH, Poyton SL. An Atlas of Metazoan Parasites in Animal Tissues. Washington, DC: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology; 2006.

2. Klimpel S, Palm HW. Anisakid nematode (Ascaridoidea) life cycles and distribution: Increasing zoonotic potential in the time of climate change? In: Mehlhorn H, ed. Progress in Parasitology, Parasitology Research Monographs 2. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2011:201-222.

3. Lima dos Santos CAM, Howgate P. Fishborne zoonotic parasites and aquaculture: A review. Aquaculture 2011;318:253-261.

4. Mimms SD, Shelton WL, Wynne FS, Onders RJ. Production of paddlefish. Stoneville, MS: Southern Regional Aquaculture Center Publication 437; 1999.

5. Miyazaki T, Rogers WA, Semmens KJ. Gastro-intestinal histopathology of paddlefish, Polyodon spathula (Walbaum), infected with larval Hysterothylacium dollfusi Schmidt, Leiby &Kritsky, 1974. J Fish Dis. 1988;11:245-250.

6. Nieuwenhuizen NE. Anisakis – immunology of a foodborne parasitosis. Parasite Immunol 2016; 38:548-557.