Signalment:

Four-year-old, male red-tailed boa constrictor.A four-year-old, male, 10-pound boa constrictor from a local zoo was submitted for necropsy following a 12-month duration respiratory tract disease. The illness was non-responsive to multiple antibiotics and, as the disease progressed, the animal exhibited increased respiratory effort, intermittent lethargy, and anorexia.

Gross Description:

The animal was in thin body condition. There was extensive replacement of up to 80% of the normal pulmonary parenchyma by coalescing granulomas.Â

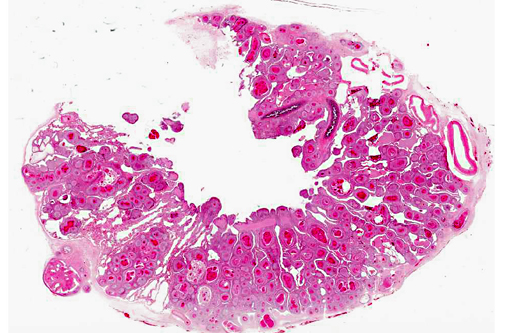

Histopathologic Description:

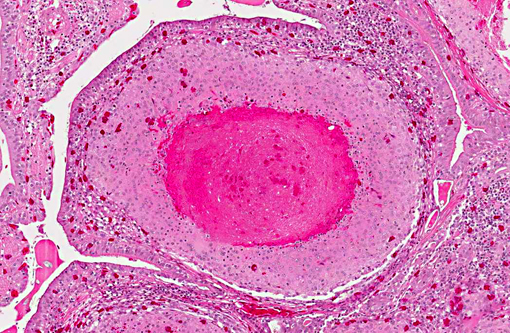

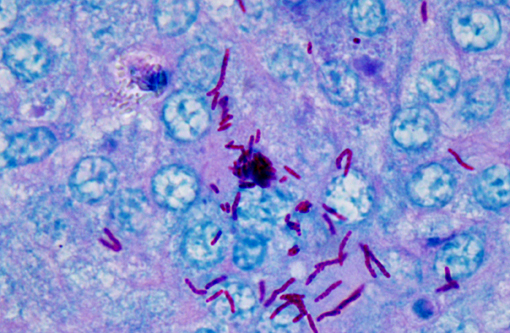

The normal pulmonary architecture is predominately effaced by coalescing granulomas. The parabronchial submucosa and air capillary interstitium are moderately to markedly expanded by granulomas, which extend into and variably occlude air spaces and faveoli. The granulomas are composed of central necrotic debris surrounded by large numbers of epithelioid macrophages admixed with low numbers of heterophils and few lymphocytes and rare giant cells. Moderate numbers of macrophages, lymphocytes, and heterophils infiltrate the interstitium between granulomas with mild fibrosis. Ziehl-Neelsen staining revealed large numbers of acid-fast bacilli within macrophages consistent with

Mycobacterium spp.Â

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Pneumonia, granulomatous, chronic, severe.

Condition:

Mycobacterium marinum

Contributor Comment:

Spontaneous mycobacterial infections have been reported in a wide variety of reptiles, including snakes, turtles, lizards, and crocodiles and descriptions of mycobacterial infections in reptiles have been reported since the early 1900s.(2,3,4)

Mycobacterium marinum is a ubiquitous opportunistic pathogen and is the predominant mycobacterial pathogen reported in snakes. The original source of infection in captive reptiles is likely the environment, whether its introduction into the exhibit is via plant matter or other inanimate objects, or via a previously infected animal.2 Infection is believed to be acquired by ingestion of infected material or via defects in the integumentary or respiratory systems.(1,4) Mycobacterial infections in reptiles can cause systemic illness accompanied by nonspecific signs such as anorexia, lethargy, and wasting.(3) Gross lesions present as grayish-white nodules present in the affected tissue. Histopathologic examination illustrates classic granulomas with a central core of necrotic debris surrounded by epithelioid macrophages.Â

Early diagnosis of mycobacterial diseases in captive reptiles is crucial to limiting the extent of disease transmission. The detection of mycobacteria among captive animals in zoos is concerning and treatment is often not advised considering the chronic and often advanced state of the disease, risk of infection to animals within the same and other exhibits, transfer of animals with unrecognized infection, and spread of infection to animal handlers.(1,2) Additionally, no successful treatment of infection with

Mycobacterium spp. has been reported in reptiles.(3)

JPC Diagnosis:

Lung: Pneumonia, interstitial, granulomatous, diffuse, severe.Â

Conference Comment:

The contributor provides a concise review of mycobacterial diseases in snakes. Conference participants discussed the differential diagnosis for granulomatous inflammation in snakes. Reptiles typically respond to infectious agents with a granulomatous inflammatory response, which is predominantly heterophilic or histiocytic, depending on both the etiologic agent and the host response.(4) Histiocytic granulomas are usually associated with intracellular pathogens, whereas heterophilic granulomas are generally associated with extracellular pathogens. In heterophilic granulomas, heterophil degranulation and central necrosis induce a strong histiocytic response; thus, both types of granulomas can progress to chronic granulomas.Â

Mycobacterium species including

M. avium, M. chelonae, M. fortuitum, M. intracellulare, M. marinum, M. phlei, M. smegmatis, and

M. ulcerans have frequently been reported to cause histiocytic granulomas in reptiles. Additionally, other intracellular bacteria from the family Chlamydiaceae, which sporadically infect reptiles, can also incite histiocytic granulomas. A retrospective study of ninety reptiles with granulomas (i.e., 48 snakes, 27 chelonians, and 15 lizards) showed that, although

Mycobacterium species other than

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MOTT) are the most important infectious agents causing granulomatous inï¬ammation in reptiles,

Chlamodyphila pneumoniae and Chlamydia-like microorganisms (e.g.,

Parachlamydia acanthamoebae and

Simikania negevensis) can also induce well-formed granulomas, and therefore should be considered in the differential diagnosis for granulomatous lesions in reptiles. Mycobacteria and chlamydia can be identified microscopically by Ziehl-Neelsen acid fact stain and immunohistochemistry for cLPS antigen, respectively; however, both of these methods are less sensitive than PCR.(4)

References:

1. Hernandez-Divers SJ, Shearer, D. Pulmonary mycobacteriosis caused by

Mycobacterium haemophilum and

M marinum in a royal python.Â

JAVMA. 2002;220(11):1661-1663.

2. Maslow JN, Wallace R, Michaels M, Foskett H, Maslow E, Kiehlbauch JA. Outbreak of

Mycobacterium marinum infection among captive snakes and bullfrogs.Â

Zoo Biology. 2002;21:233-241.

3. Slany M, Knotec Z, Skoric M, Knotkova Z, Svobodova J, Mrlik V, et al. Systemic mixed infection in a brown caiman (

Caiman crocodiles fuscus) caused by

Mycobacterium szulgai and

M. chelonae: A case report.Â

Veterinarini Medicina. 2010;55(2):91-96.

4. Soldati G, Lu ZH, Vaughan L, Polkinghorne A, Zimmermann DR, Huder JB, et al. Detection of mycobacterial and chlamydiae in granulomatous inflammation of reptiles: A retrospective study.Â

Vet Path. 2004;41:388-397.