Wednesday Slide Conference, Conference 6, Case 4

Signalment:

Adult, male African Green monkey (Chlorocebus sabeus).

History:

An adult male African green monkey had been wild caught on St. Kitts and arrived in quarantine in Maryland in November 2023 with limited clinical history prior available to September 2023.

He had four physical exams during September and October 2023 at the holding/shipping facility on St. Kitts which were unremarkable. He had received four doses of ivermectin and two doses of Drontal plus at the holding facility.

During the initial quarantine examination in November, he was noted to have mild bradycardia and a superficial injury on his distal tail. His appetite was reduced for biscuits, but he was interested in some fruit. On the technician recheck several days later he was noted to fall off his perch when stimulated. During the veterinary cage-side exam, he was bright, alert, and responsive. His head consistently tilted to the right during the exam. When gently stimulated he readily got off the perch and immediately circled to the right 1-2 times. This circling was repeatable and consistent to the right. No ataxia or nystagmus was appreciated. He was started on cerenia and appetite monitoring. A behavior consult was unremarkable. His reduced appetite continued through weekend. He was noted to have a possible right sided-tongue deviation on December 2nd but otherwise clinical signs remained relatively static (R sided head tilt w/right sided circling). Endoparasitology was positive for Schistosoma mansoni ova by fecal floatation exam on December 4th. Euthanasia was elected due to poor prognosis, and he was submitted for necropsy two days later.

Gross Pathology:

A male African Green monkey was submitted following euthanasia with a history of a positive finding of Schistosoma mansoni on recent fecal endoparasite examination. The monkey was well-hydrated, well-muscled and contained adequate body fat. On examination of the chest cavity, there were mild adhesions between the left caudal lung lobe and the thoracic wall. The lung lobes were congested with no evidence of pneumonia and these lobes floated in formalin. The heart, kidneys, liver, gallbladder, spleen, pancreas and lymph nodes appeared normal. The stomach contained a moderate amount of ingesta and formed content was present in the colon. No abnormalities were noted involving the mesentery or mesenteric lymph nodes. The urinary bladder and testes appeared normal. The brain appeared grossly normal.

Laboratory Results:

Endoparasitology was performed and was positive for Schistosoma mansoni ova and Entamoeba sp.

Microscopic Description:

Histopathology revealed multiple small granulomas throughout the hepatic parenchyma containing Schistosoma ova. A solitary granuloma containing a Schistosoma ova was noted in one of several lung sections. Mild nonuppurative pulmonary perivasculitis was present. Examination of sections of cerebrum, cerebellum, medulla and spinal cord revealed meningoencephalitis with multiple granulomas containing Schistosoma ova in the cerebrum, cerebellum and medulla. Sections of the middle/inner ears appeared normal. No other histologic lesions were noted.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis:

Cerebrum: encephalitis, granulomatous, multifocal containing Schistosoma mansoni ova.

Contributor’s Comment:

Schistosomiasis (also known as bilharziasis) is named after Theodor Bilharz, a German surgeon who discovered S. haematobium in 1851.

Schistosomiasis is a major problem worldwide with over 230 million people infected and approximately 200,000 deaths annually. It has been reported in over 52 countries primarily affecting the Eastern Mediterranean, South American, Africa, and the Caribbean.11 The cause is a blood borne trematode, Schistosoma sp. with three primary species – S. mansoni, S. japonicum and S. haematobium. Laboratory identification commonly relies on identification of parasitic eggs in fecal material. The morphology of the eggs is characteristic for each species with S. mansoni having a distinct lateral spine.

The life cycle of Schistosoma mansoni is complex and indirect, requiring infection of an intermediate freshwater Biomphalaria snail.

Cercariae are released after 4-6 weeks from infected snails and may survive up to 72 hours.

Cercariae attach to the skin of definitive hosts and penetrate the skin to enter dermal vessels, ultimately reaching the pulmonary and hepatic vasculature with maturation to adults in mesenteric veins. Male and female adults maintain a copulatory union in the mesenteric vessels. Ova travel to the lumen of the intestinal tract, are shed in feces, and hatch to free swimming cercariae which can survive up to 3 weeks before infecting appropriate snails to complete the life cycle.11

Schistosomiasis is a significant zoonotic disease. While humans are the definitive host, other vertebrate animals may play a significant role with the ability to transmit the agent within the environment. Wild rodents, domesticated animals, and nonhuman primates can serve as additional hosts for this infection.2

Nonhuman primates including African green monkeys, patas monkeys, chimpanzees, and baboons have become infected with Schistosoma mansoni in a number of different African and Caribbean countries.5 In 2019, an African green monkey from St. Kitts tested positive on fecal examination for S. mansoni. This was the first positive report in an African green monkey on St. Kitts after the island was declared negative for the presence of S. mansoni during the preceding 50 years.6

Diagnosis of Schistosoma mansoni relies primarily on endoparasitologic examination of fecal matter for shed ova. Due to possible discontinuous and insufficient shedding of ova fecal examination should be conducted analyzing several samples collected on alternate days. PCR analyses for Schistosoma ITS-2 DNA sequence can be employed and indirect serologic assays are also available. Clinical findings may include fever, hepatosplenomegaly, eosinophilia and possibly CNS signs.8 The treatment of choice for schistosomiasis is praziquantel which targets adult parasites. The drug induces paralysis of the adult parasites which detach from vessel walls allowing the ability of host’s immune responses to target the parasites. Additional drug therapies and several vaccines are currently in development.8

Morbidity is primarily due to the significant antigenicity of the circulating ova which may reach a variety of organs/tissues including the liver, spleen, lung, intestinal tract, testes, epididymis, prostate, uterus, eye, brain and spinal cord.4 The inflammatory cell reaction in schistosomiasis is principally due to the intense granulomatous reaction to the dispersed ova. Ova become surrounded by T and B lymphocytes, epithelioid macrophages, foreign body type giant cells, eosinophils, and limited numbers of neutrophils. Chronic infection results in the development of fibrosis with collagen deposition (1). Numbers of studies of the granulomas have identified various lymphocytic subsets including B cells, Th17 cells and Treg cells, as well as various cytokines, chemokines and vascular endothelial factor.3

Neurologic involvement of Schistosoma mansoni infection can affect both the brain and spinal cord. The development of CNS signs depends on the relative numbers of ova within the brain and spinal cord and the severity of the accompanying inflammatory cell reaction. Clinical signs may include ataxia, nystagmus, visual impairment, and seizures. Vascular embolization of individual eggs is the most common mode for CNS involvement.7

Contributing Institution:

Diagnostic and Research Services Branch, Division of Veterinary Resources, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Maryland

JPC Diagnosis:

Cerebrum: Meningoencephalitis, granulomatous and eosinophilic, multifocal to coalescing, moderate with perivascular schistosome eggs.

JPC Comment:

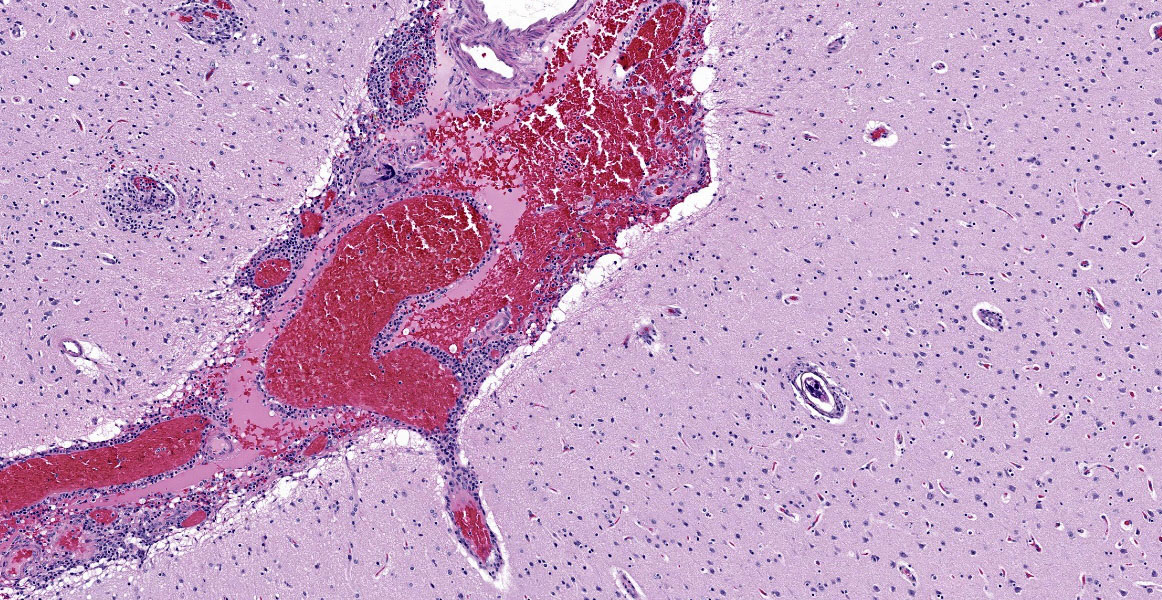

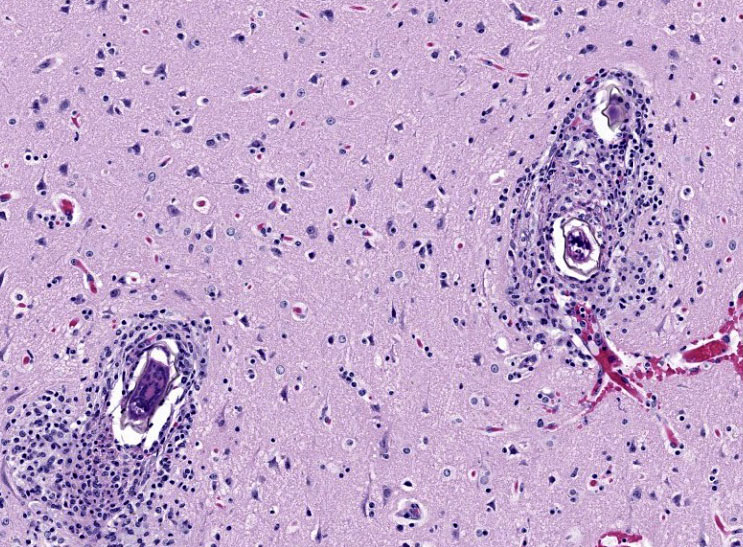

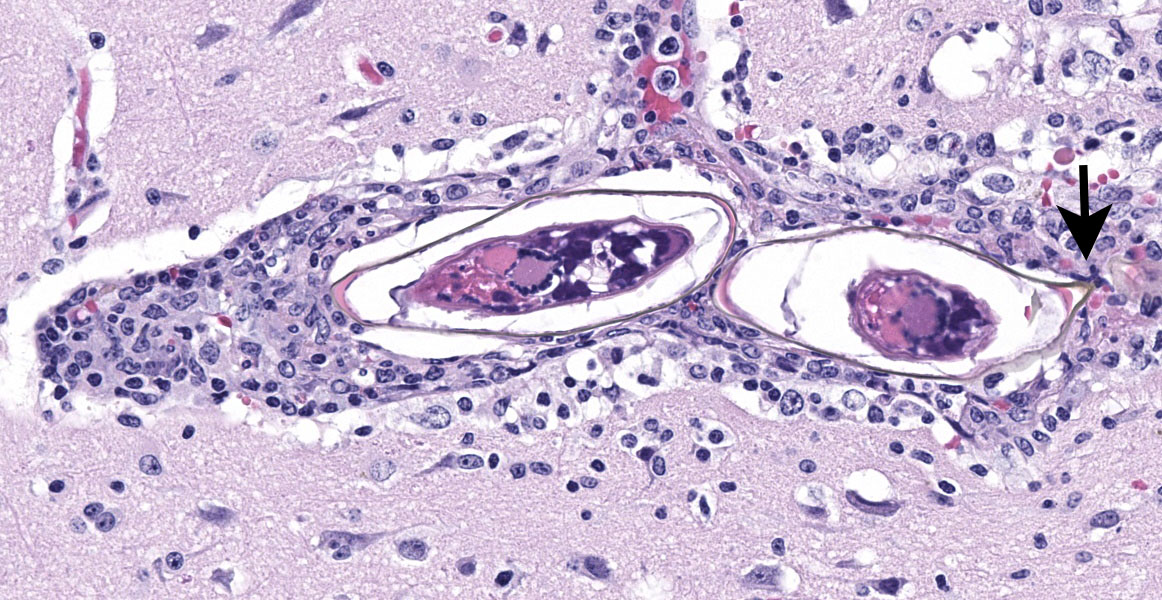

The final case of this conference features a short description and an interesting backstory. Dr. Eckhaus actually submitted this case and was intently interested in the development of this lesion given the lack of overt pathology at necropsy. From subgross (figure 4-1), perivascular basophilia is indicative of the inflammatory response elicited by circulating schistosome ova within and extending from blood vessels (figure 4-2). Recognizing that these granulomas are centered on blood vessels and the lack of other life stages in section (larva or adult) is helpful for ruling out other metazoan parasites as the cause of the meningoencephalitis in this case. We were able to speciate the schistosome as S. mansoni by the distinct lateral spine (figure 4-4, arrow) which S. japonicum and S. haematobium lack. Conference participants briefly reviewed other sections of this case provided by Dr. Eckhaus, but were unable to identify adult schistosomes in section. As this animal was dewormed with praziquantel multiple times before developing overt clinical disease, it is likely that deworming likely removed adult trematodes from the vessels, but had no effect on the eggs already present within the bloodstream or perivascular tissues.

Finally, we elaborate further on the connection between granulomas and the life cycle of Schistosoma.9,10 The ova of S. mansoni are metabolically active and highly antigenic, a combination that allows them to recruit inflammatory cells as a means to migrate from blood vessels into the lumen of the gut for excretion.9,10 The ova secretes factors to potentiate attachment to the endothelium as well as bias the immune response of the host towards a Type 2 (Th2) response with marked increases in IL-4, -5, and -13.9,10 Interestingly, these same proteins can also upregulate cellular adhesion molecules such as ICAM-1 on endothelial cells and increase recruitment of inflammatory cells to the nascent granuloma. The exact mechanism of movement through the extracellular milieu is unclear, though the role of M2 macrophages and matrix metalloprotease activity is likely.9 Fibrosis induced by the M2 phenotype may also partially protect ova from eosinophils and basophils.10 In addition, ova also have the ability to increase plasminogen activation which serves to clear fibrin and fibronectin alike. Likewise, how exactly the ova ‘eggs-its’9 out of this granuloma to enter the gut lumen has not been described, though interactions between the ova, gut microbiome, and macrophages are a possibility. Interestingly, humans and mice models with T-cell deficiencies shed fewer ova in their feces, highlighting the role of Th2 polarity in the life cycle of this parasite.

Finally, the timing of this immune relationship is key as immature ova do not recruit inflammatory cells and evade (initially) granuloma formation.10 Additionally, schistosome ova only undergo development within the host. Together, this may be adaptive in that it ensures viable, developed miracidia are ready to be released to continue the life cycle.

References:

- Carvalho OA. Mansonic neuroschistosomiasis. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2013 Sep;71(9B):714-6.

- Modena CM, dos Santos Lima W, Coelho PM. Wild and domesticated animals as reservoirs of Schistosomiasis mansoni in Brazil. Acta Trop. 2008 Nov-Dec;108(2-3):242-4.

- Giorgio S, Gallo-Francisco PH, Roque GAS, Flóro E, Silva M, Granlulomas in parasitic diseases: the good and the bad. Parasitol Res. 2020 Oct;119(10):3165-3180.

- Gryseels B. Schistosomiasis. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America; June 2012, 383-397.

- Kebede T, Bech N, Allienne JF, Olivier R, Erko B, Boissier. Genetic evidence for the role of non-human primates as reservoir hosts for human schistosomiasis. J.PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020 Sep 8;14.

- Ketzis JK, Lejeune M, Branford I, Beierschmitt A, Willingham AL. Identification of Schistosoma mansoni Infection in a Nonhuman Primate from St. Kitts More than 50 Years after Interruption of Human Transmission. Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103(6):2278-2281.

- Llanwarne F, Helmby H. Granuloma formation and tissue pathology in Schistosoma japonicum versus Schistosoma mansoni infections. Parasite Immunol. 2021 Feb;43(2):e12778.

- Ponzo E, Midiri A, Manno A, Pastorello M, Biondo C, Mancuso G. Insights into the epidemiology, pathogenesis, and differential diagnosis of schistosomiasis. Eur J Microbiol Immunol (Bp). 2024 Mar 18;14(2):86-96.

- Schwartz C, Fallon PG. Schistosoma "Eggs-Iting" the Host: Granuloma Formation and Egg Excretion. Front Immunol. 2018 Oct 29;9:2492.

- Takaki KK, Rinaldi G, Berriman M, Pagán AJ, Ramakrishnan L. Schistosoma mansoni Eggs Modulate the Timing of Granuloma Formation to Promote Transmission. Cell Host Microbe. 2021 Jan 13;29(1):58-67.

- Verjee MA. Schistosomiasis: still a cause of significant morbidity and mortality. Res Rep Trop Med. 2019;10:153–63.