Signalment:

Gross Description:

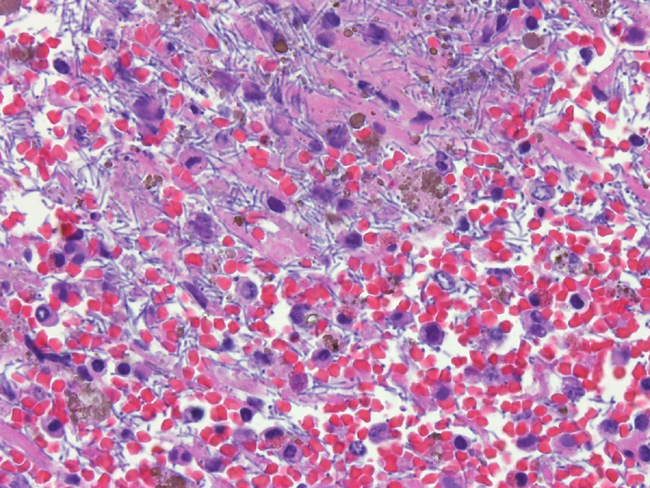

Histopathologic Description:

Morphologic Diagnosis:

Lab Results:

Condition:

Contributor Comment:

Anthrax is a disease syndrome recognized for centuries and a pathogen that is widely distributed around the world. In 1823 anthrax was the first disease of humans and animals shown to be caused by a micro-organism.1 Anthrax occurs sporadically in Australia affecting sheep, cattle, infrequently pigs and rarely goats and horses.4 It is largely confined to the "anthrax belt" which extends through the middle of the Australian states of New South Wales and into northern and central Victoria.3,4 This laboratory in Victoria would typically diagnose 2 or 3 cases of anthrax per year. In January and February 2007, there was an unusual outbreak of anthrax in central Victoria with this laboratory diagnosing 37 positive anthrax cases, on eight farms from approximately 300 submissions from the surveillance area. The last significant outbreak of anthrax in Victoria was between January and March 1997, when anthrax was diagnosed on 83 properties with 202 cattle and 4 sheep confirmed to have died of anthrax.5 In Australia, effective control of anthrax infection is achieved by vaccination of in contact farms and livestock.

Ruminants are typically infected with anthrax by ingestion of spores that germinate in the intestinal tract to form encapsulating vegetative cells that replicate and spread to the regional lymph nodes and then disseminate systemically.2 Infection may also occur by cutaneous abrasion and insect bites.1 Extremely rarely it is possible, in cattle, to initiate an infection by inhaling spores while grazing dry dusty contaminated sites.1 Bacillus anthracis produces exotoxins termed lethal toxin and edema toxin. The toxins and the capsule of the bacteria inhibit phagocytosis, increase capillary endothelial permeability and delay clotting.1 Animal species vary in their susceptibility to anthrax infection. Species easily infected with anthrax include cattle, goats, sheep, monkey, mouse, guinea pigs, horses and chimpanzees. Species resistant to anthrax but once infection is establish are highly susceptible to effects of the exotoxins include dog, pig and NIH black and Fisher rats.1 Humans can be infected with anthrax by inhalation, ingestion or cutaneous abrasions. Human cases of anthrax are rare in Australia and there have been only four cases in the last ten years, all have been the cutaneous form and most of the cases have been in farmers or rendering plant workers.6

JPC Diagnosis:

Conference Comment:

Infection of both humans and animals can occur through ingestion, percutaneously, or more rarely through inhalation of anthrax spores. Under certain conditions, spores have been known to remain viable in the soil up to 200 _50 years. Germination of spores occurs between 20o - 40o C and in conditions of greater than 80% relative humidity. Upon ingestion of spores, the organisms quickly germinate to the encapsulated toxin-producing vegetative form. The capsule is a poly-D-glutamate capsule that inhibits phagocytosis.1

Lethal toxin inhibits mitogen-activated protein kinase-kinase and results in terminal shock through the release of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin-1 (IL-1). Edema factor results in altered intracellular water and ion concentrations through the abnormal production of c-AMP. Edema factor has also been implicated in preventing mobilization and activation of leukocytes. The presence of the capsule and two toxins effectively results in prevention of phagocytosis, increased capillary endothelial permeability and decreased blood clotting ability.1

References:

2. Fry MM, McGavin MD. Bone marrow, blood cells and lymphatic system. In Pathologic Basis of Veterinary Disease. 4th ed McGavin MD, Zachary JF. p811. Mosby Elsevier, St. Louis, 2007.

3. Muller JD, Wilks CR, O'Riley KJ et al. Specificity of an immunochromatographic test for anthrax. Aust Vet J 82 (4) 220-222. 2004.

4. Snedden HR, Albiston HE. Bacterial diseases. Diseases of Domestic Animals in Australia Part 5 Volume 1. pp. 12-26. Commonwealth Government Printer, Canberra, Australia. 1965.

5. Turner AJ, Galvin JW, Rubira RJ et al. Anthrax explodes in an Australian summer. J Appl Microbiol 87(2) 196-199. 1999.

6. Kolbe A, Yuen MG, Doyle BK. A case of human cutaneous anthrax. Med J Aust. 185 (5) 281-282. 2006.