WSC 2022-2023

Conference 18

Case III:

Signalment:

A 5-year-old, female, bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus).

History:

The bald eagle was found on the side of the road and looked like it couldn’t walk properly. On arrival at the LSU Wildlife Hospital, the bald eagle was emaciated, lethargic, and anemic (PCV: 23%). The left metacarpal joints were swollen and had purulent exudates. She had severe louse infestation, and fecal flotation revealed whipworm eggs and strongyle eggs. The eagle was treated with fluids, Frontline, vitamin B complex, iron dextran, meloxicam, ceftiofur, and piscivore diet. Over ten days the eagle got more alert and ate fish and rabbit on her own, but then declined and found dead in her kennel, 13 days after admission.

Gross Pathology:

The bald eagle was found on the side of the road and looked like it couldn’t walk properly. On arrival at the LSU Wildlife Hospital, the bald eagle was emaciated, lethargic, and anemic (PCV: 23%). The left metacarpal joints were swollen and had purulent exudates. She had severe louse infestation, and fecal flotation revealed whipworm eggs and strongyle eggs. The eagle was treated with fluids, Frontline, vitamin B complex, iron dextran, meloxicam, ceftiofur, and piscivore diet. Over ten days the eagle got more alert and ate fish and rabbit on her own, but then declined and found dead in her kennel, 13 days after admission.

Laboratory Results:

Aerobic bacterial culture (liver): E. coli (moderate), Enterococcus canintestini (moderate)

Salmonella culture (liver): Negative

Fecal flotation test: No parasites seen

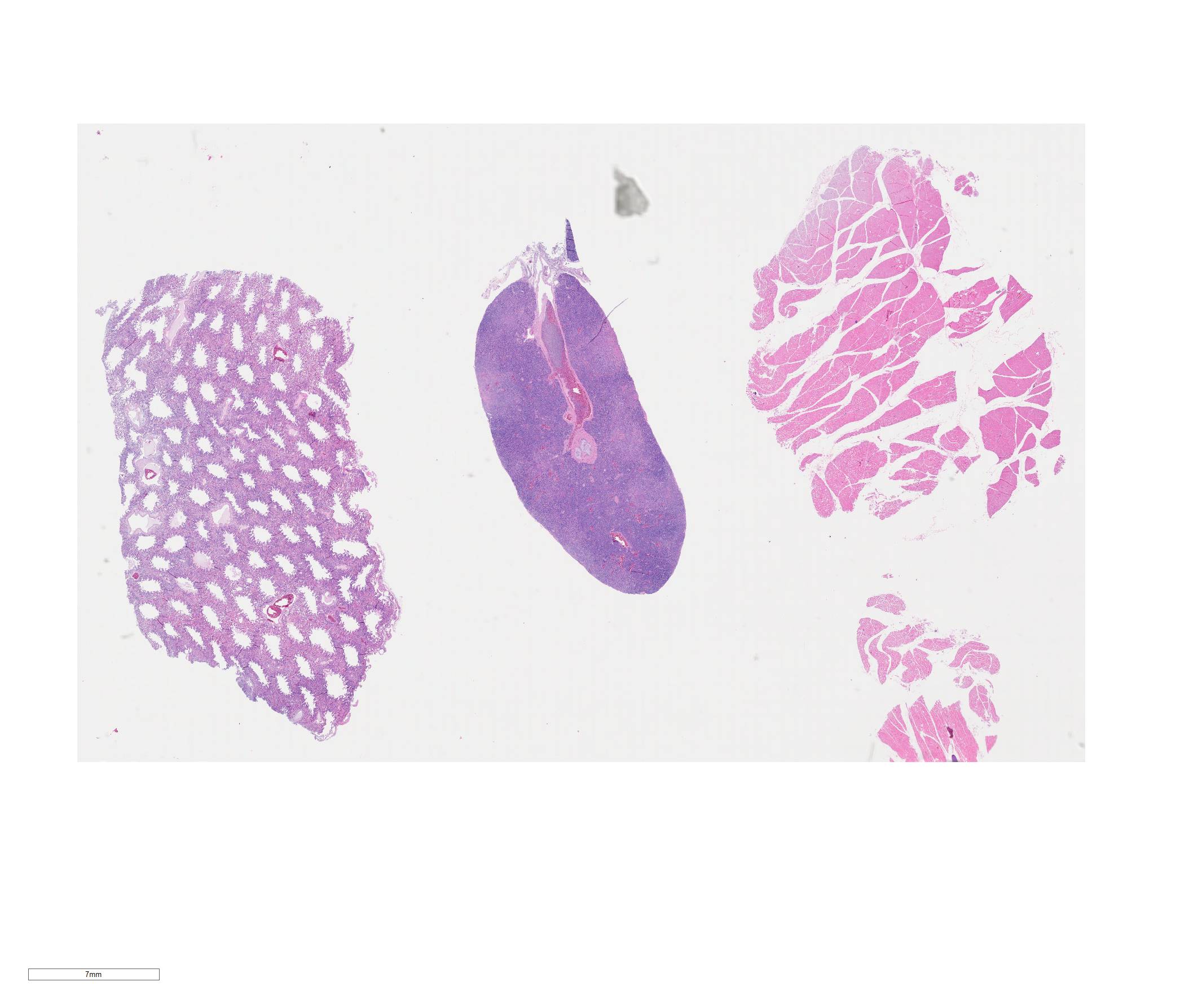

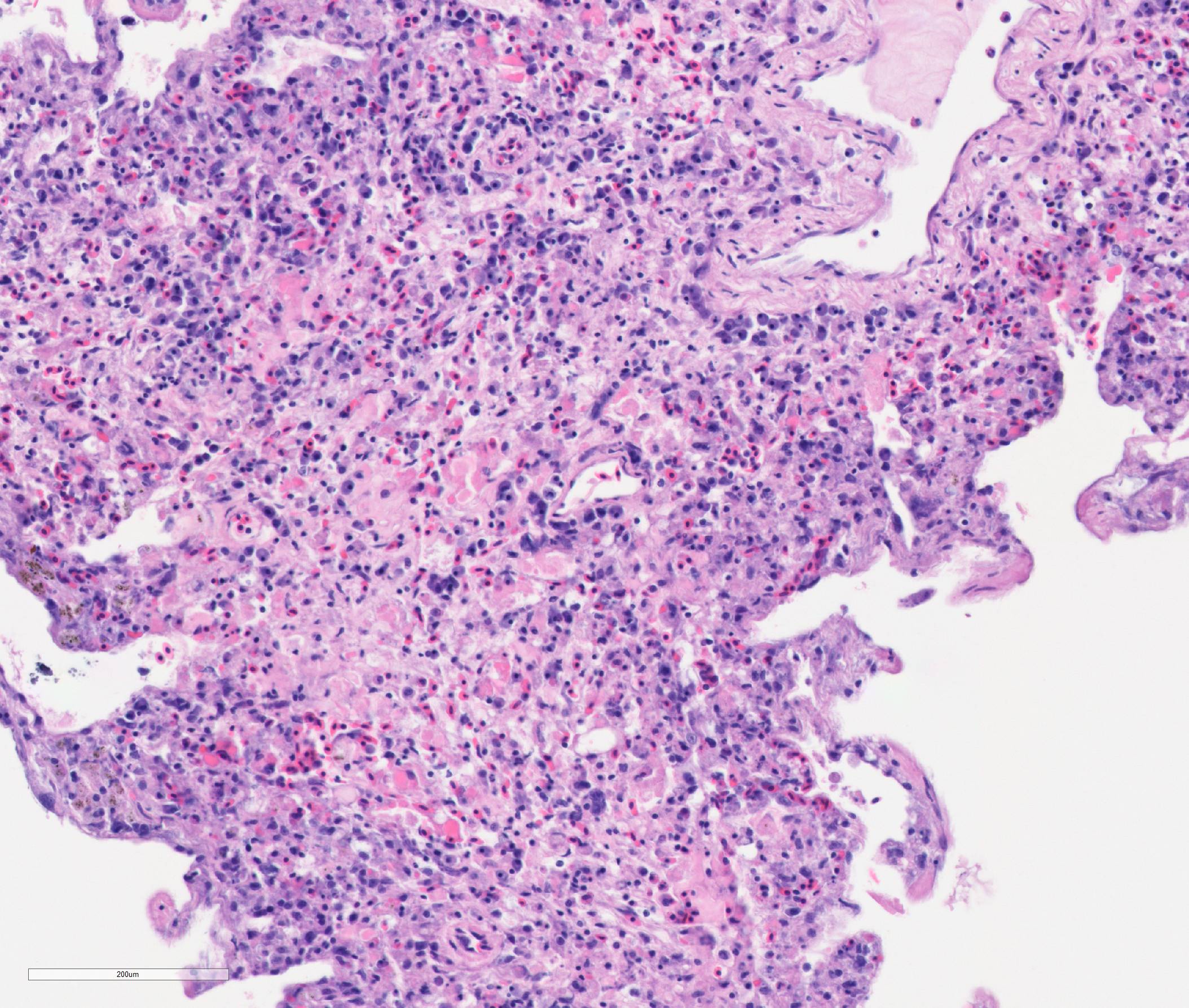

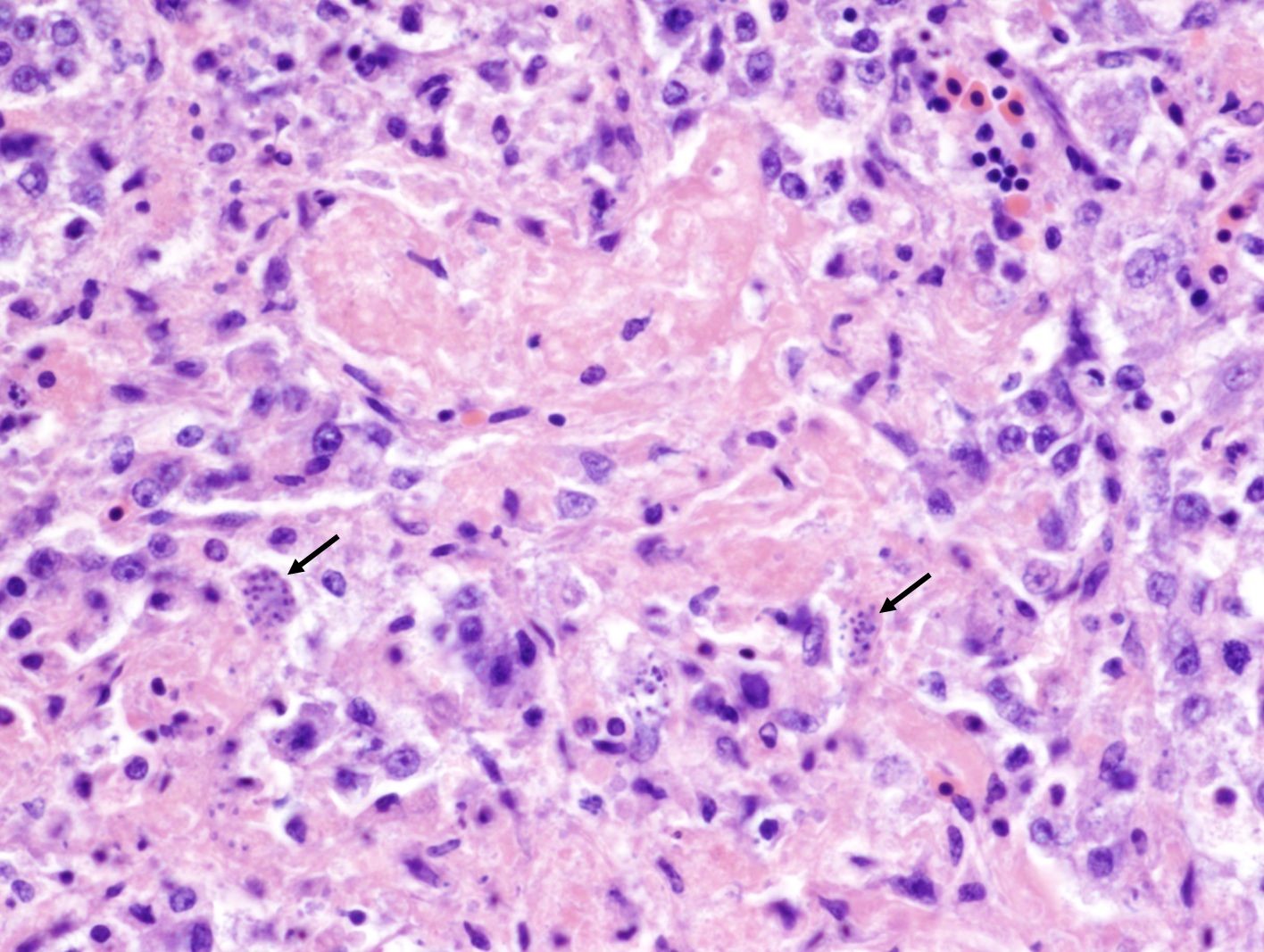

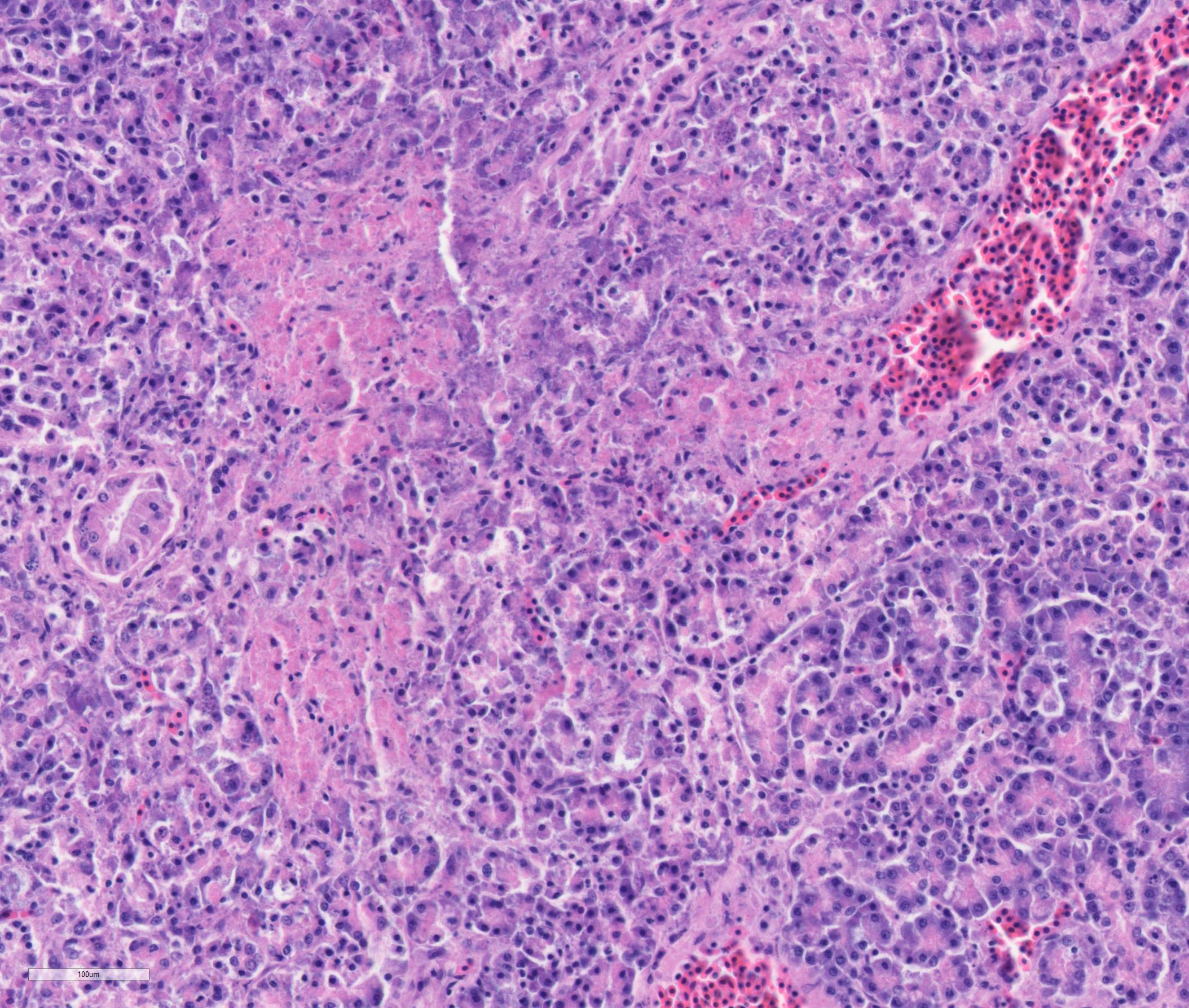

Microscopic Description:

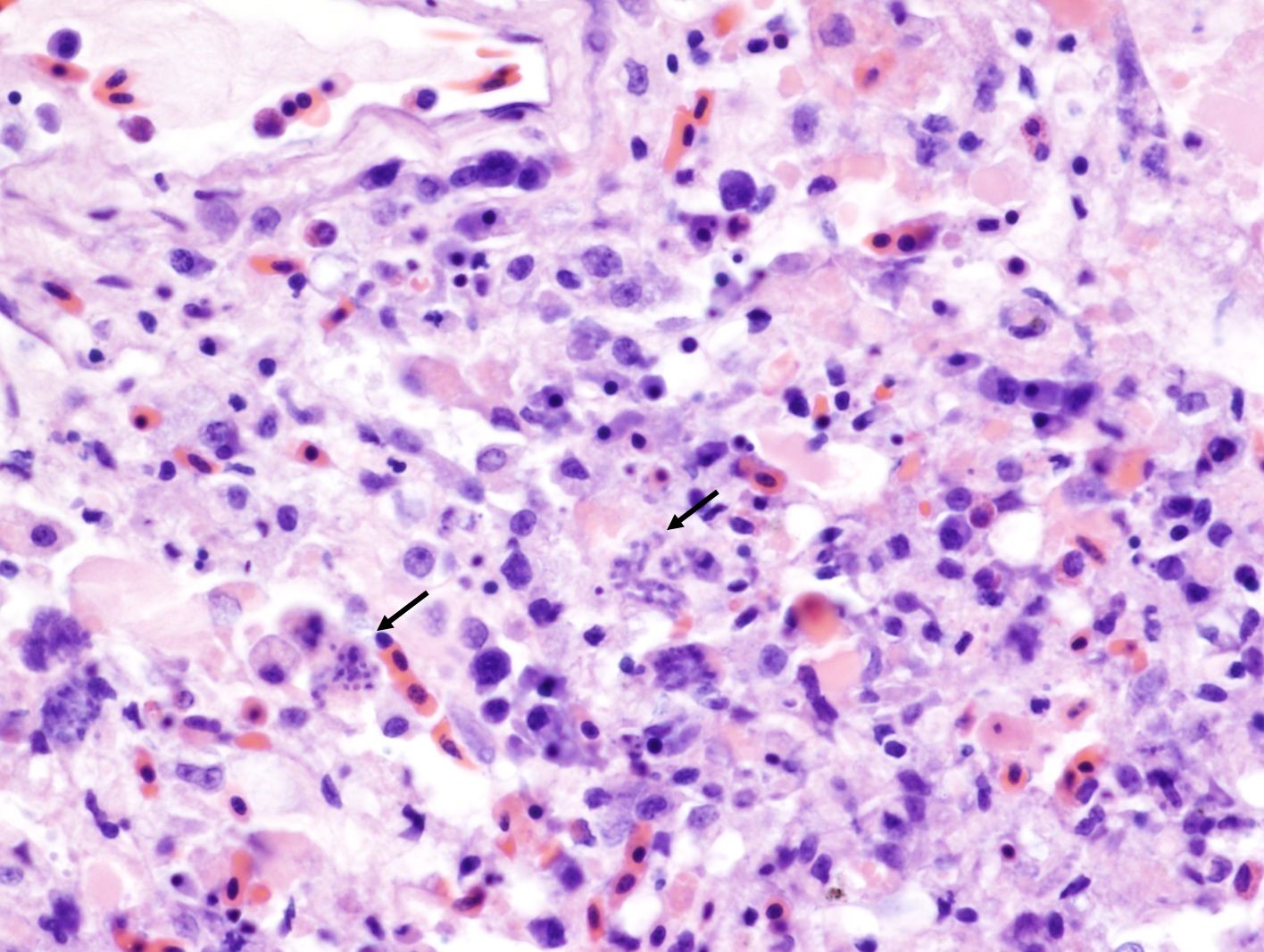

Lung: The parabronchial wall is diffusely infiltrated by large numbers of plasma cells, lymphocytes, fewer Mott cells, and heterophils, narrowing and obliterating the air capillaries. Some air capillaries contain eosinophilic proteinaceous material mixed with fibrin. Frequently within presumed endothelial cells, there are clusters of 1-2 x 3-5 µm, elongated, basophilic, merozoites with a small dark basophilic nucleus. Occasional interatrial septa have small aggregates of macrophages containing brown-black pigment (pneumoconiosis).

Pancreas: There is multifocal to coalescing necrosis associated with multiple clusters of merozoites. Mild fibroplasia and ductular reaction are present adjacent to the necrotic areas. Low numbers of plasma cells and lymphocytes infiltrate the interstitium. The capsule is partially covered by fibrin, and the capsule abutting the necrotic area is thickened by fibroplasia and infiltration of macrophages.

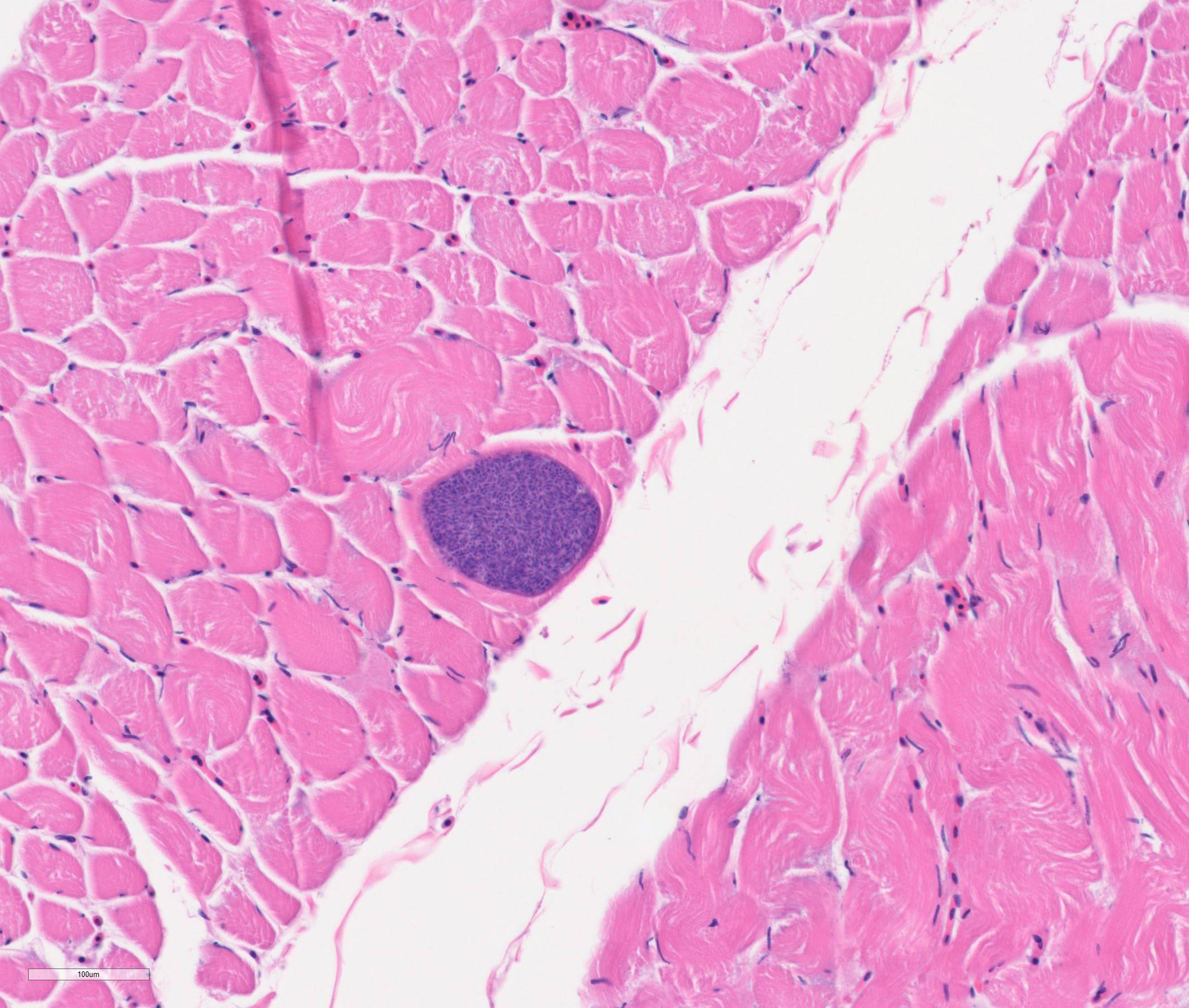

Skeletal muscle: Occasional myofibers contain sarcocysts measuring up to 80 x 150 µm, containing large numbers of bradyzoites. Sporadic myofibers are degenerate and necrotic, characterized by loss of cross-striation and fragmentation of the sarcoplasm. Occasionally, necrotic myofibers are replaced by infiltration of macrophages and lymphocytes.

Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnoses:

Lung: Severe subacute diffuse lymphoplasmacytic interstitial pneumonia with intraendothelial apicomplexan merozoites

Skeletal muscle: Multiple sarcocysts; mild multifocal muscular degeneration and necrosis

Pancreas: Moderate subacute multifocal to coalescing necrotizing pancreatitis with intralesional apicomplexan merozoites

Contributor’s Comment:

In this case, merozoites consistent with Sarcocystis sp. and associated necrotizing inflammation was noted in multiple organs including the lung, liver, pancreas, cerebellum, and to a lesser extend in the cerebrum, and sarcocysts were noted in the skeletal and cardiac muscle. The final diagnosis on this case was systemic sarcocystosis. Chronic septic arthritis of the left carpal joint was also noted.

Sarcocystis spp. are apicomplexan protozoal parasites that infect mammals, birds, and reptiles. More than 200 species are known in this genus. Sarcocystis spp. have an obligate 2-host life cycle. The sexual stages develop in a predator host (definite host), whereas the asexual phases develop in the prey animal (intermediate host). The intermediate host ingests sporocysts or sporulated oocysts through herbage contaminated by the definite host’s feces. Sporozoites are released and invade endothelial cells where they undergo schizogony. One or two generations of schizogony take place. The merozoites derived from these generations invade skeletal and cardiac myocytes where they develop into thin-walled cysts initially containing round metrocytes, which repeatedly divide through a process termed endodyogeny to produce numerous banana-shaped bradyzoites. The definite host consumes the skeletal muscle with the sarcocysts containing bradyzoites. The sexual cycle is developed in the intestinal epithelium of the predatory host.5,9

In most cases, sarcocystosis is subclinical in the definitive or intermediate host. In definitive hosts, it causes intestinal sarcocystosis which is often asymptomatic or self-limiting. For intermediate hosts, muscular sarcocystosis is a common incidental finding on postmortem examination. However, certain Sarcocystis species can cause serious diseases in intermediate hosts. Those include Sarcocystic neurona causing equine protozoal myeloencephalitis in horses and S. calchasi causing pigeon protozoal encephalitis in domestic pigeons.

Certain Sarcocystis spp. are zoonotic, and Sarcocystosis may be underdiagnosed in humans. Humans are definite hosts of S. hominis, S. heydorni, and S. suihominis. Consuming undercooked beef (S. hominis, S. heydorni) and pork (S. suihominis) is the route of infection, which causes intestinal sarcocystosis. Humans also serve as intermediate hosts for other Sarcocystis spp. by accidental consumption. One example is S. nesbitti of which a predatory snake is thought to be the definite host. In these circumstances, muscular sarcocystosis can develop.2,9

At least six species of Sarcocystis infect birds.11 Two species are known to cause serious clinical diseases in birds. Sarcocystis calchasi, the causative agent of pigeon protozoal encephalitis, has been first described in domestic pigeons and causes sporadic cases of encephalitis in Columbidae. Epizootics associated with S. calchasi-induced encephalitis have been reported in wild feral rock pigeons6, in three different psittacine species in a zoological exhibit7, and in wild Brandt’s cormorants 1, all of which occurred in California. Experimental studies demonstrated a biphasic disease in domestic pigeons: an acute schizogonic phase and a late phase with neurologic signs. According to a study, inflammatory lesions in the cerebrum were identified as early as 20 days post infection (d.p.i.) while the onset of neurologic signs appeared at 47 d.p.i. As the numbers of sarcocystis organisms or the amount of DNA did not increase with the increase of cerebral inflammation, a delayed-type hypersensitivity was proposed as the pathogenesis of S. calchasi-induced encephalitis.4 The definite hosts of S. calchasi are northern goshawks (Accipiter gentilis) and European sparrowhawks (A. nisus) in Europe and Cooper’s hawks (A. cooperii) and red-tailed hawks (Buteo jamaicensis) in North America.8

Sarcocystis falcatula, which also can cause fatal sarcocystosis in birds, uses Virginia opossums (Didelphis virginiana) as a definite host. Natural intermediate hosts are cowbirds and grackles. Psittacine birds, especially old world psittacine, are known to be susceptible to S. falcatula infection. The primary lesion is pulmonary congestion, edema, and hemorrhage with intravascular merozoites, but myositis and encephalitis also occur. Clinical disease also has been reported in Victoria crowned pigeons characterized by sudden death caused by pulmonary sarcocystosis.10 Birds of prey including free-ranging bald eagles, golden eagles12, and a great horned owl13 also have been reported with fatal pulmonary and/or neurologic sarcocystosis caused by S. falcatula. S. ryleyi affects waterfowls and usually is an incidental finding at necropsy.

According to Wünschmann et al.12, among three bald eagles and one golden eagle that had fatal Sarcocystis falcatula infection, two bald eagles had blood lead concentration consistent with subclinical lead intoxication, and one had lead intoxication. It was not discussed in this article whether the lead intoxication played a role in the disease susceptibility, but we were wondering if lead intoxication make the birds more susceptible to sarcocystosis. In the present case, the infection was disseminated affecting multiple organs, compared to previously reported sarcocystosis cases in raptors. Heavy metal level was not measured in this case, but the chronic septic arthritis may have caused immunosuppression predisposing the fatal systemic sarcocystosis.

In this case, the diagnosis was made based on the morphology and the location (pulmonary endothelium) of the apicomplexan parasites, and further characterization of the organism was not performed. PCR is usually used for confirmation of sarcocystosis and identifying the species.

Contributing Institution:

Department of Pathobiological Sciences and Louisiana Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory, School of Veterinary Medicine, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, LA, USA

https://www.lsu.edu/vetmed/laddl/

https://www.lsu.edu/vetmed/pbs/index.php

JPC Diagnosis:

- Lung: Pneumonia, interstitial, lymphoplasmacytic and histiocytic, diffuse, marked with intraendothelial apicomplexan merozoites.

- Pancreas: Pancreatitis, necrotizing, multifocal to coalescing, moderate with intraendothelial apicomplexan merozoites.

- Skeletal muscle: Sarcocysts, numerous.

JPC Comment:

As the contributor describes, Sarcocystis calchasi is one of the main pathogenic Sarcocystis species in birds and primarily infects Columbiformes and Psittaciformes. The first documented cases of infection in Galliformes were recently reported in a 2022 Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation article.3 Two captive vulturine guineafowl, ground dwelling birds, developed acute and rapidly fatal infections after having been moved to a new enclosure with other avian species.3 The first bird presented unable to stand and experienced progressive neurologic signs.3 The second bird presented shortly after the first with nonspecific signs of lethargy and weight loss, and both animals died despite ponazuril therapy.3 The animals had nonsuppurative meningoencephalitis with perivascular lymphoid cuffing and glial nodule formation, and one animal had protozoal schizonts in areas of inflammation.3 Both animals were PCR positive for Sarcocystis, and sequencing indicated the species was S. calchasi.3

References:

- Bamac OE, Rogers KH, Arranz-Solís D, et al. Protozoal encephalitis associated with Sarcocystis calchasi and falcatula during an epizootic involving Brandt’s cormorants (Phalacrocorax penicillatus) in coastal Southern California, USA. Int J Parasitol: Parasites Wildl. 2020;12: 185-191.

- Fayer R, Esposito DH, Dubey JP. Human infections with Sarcocystis species. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28: 295-311.

- Gadsby S, Garner MM, Bolin SR, Sanchez CR, Flaminio KP, Sim RR. Fatal Sarcocystic calcahsi-associated meningoencephalitis in 2 captive vulturine guineafowl. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2022; 34(3):543-546.

- Maier K, Olias P, Enderlein D, et al. Parasite distribution and early-stage encephalitis in Sarcocystis calchasi infections in domestic pigeons (Columba livia f. domestica). Avian Pathol. 2015;44: 5-12.

- Maxie MG. Jubb, Kennedy & Palmer’s pathology of domestic animals. Vol 1. 6th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. 2015.

- Mete A, Rogers KH, Wolking R, et al. Sarcocystis calchasi outbreak in feral rock pigeons (Columba livia) in California. Vet Pathol. 2019;56: 317-321.

- Rimoldi G, Speer B, Wellehan Jr JF, et al. An outbreak of Sarcocystis calchasi encephalitis in multiple psittacine species within an enclosed zoological aviary. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2013;25: 775-781.

- Rogers KH, Arranz-Solís D, Saeij JP, Lewis S, Mete A. Sarcocystis calchasi and other Sarcocystidae detected in predatory birds in California, USA. Int J Parasitol: Parasites Wildl. 2022;17: 91-99.

- Rosenthal BM. Zoonotic sarcocystis. Res Vet Science. 2021;136: 151-157.

- Suedmeyer W, Bermudez AJ, Barr BC, Marsh AE. Acute pulmonary Sarcocystis falcatula-like infection in three Victoria crowned pigeons (Goura victoria) housed indoors. J Zoo Wildl Med. 2001;32: 252-256.

- Terio KA, McAloose D, Leger JS. Pathology of Wildlife and Zoo Animals. Academic Press. 2018.

- Wünschmann A, Rejmanek D, Conrad PA, et al. Natural fatal Sarcocystis falcatula infections in free-ranging eagles in North America. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2010; 22: 282-289.

- Wünschmann A, Rejmanek D, Cruz-Martinez L, Barr BC. Sarcocystis falcatula—associated encephalitis in a free-ranging Great Horned Owl (Bubo virginianus).J Vet Diagn Invest. 2009;21: 283-287.